Sometimes I came across a tree which seemed like a Buddha or a Jesus: loving, compassionate, still, unambitious, enlightened, in eternal meditation, giving pleasure to a pilgrim, shade to a cow, berries to a bird, beauty to its surroundings, health to its neighbours, branches for the fire, leaves for the soil, asking nothing in return, in total harmony with the wind and the rain. How much I can learn from a tree! The tree is my church, the tree is my temple, the tree is my mantra, the tree is my poem and my prayer.”

—Satish Kumar, No Destination

[B]orn restless, from the trees he learned patience, from the grasses underfoot, persistence. Little wonder, then, that when asked to give a workshop on reverential ecology at the Youth at the Millennium symposium in Kyoto in the fall of 1999, Satish Kumar led participants out of the conference hall and down the road to Hirano Shrine. At the orange gateway, Kumar invited everyone to walk with him wordlessly through the shrine’s autumnal groves of cherry trees, scarlet maples and golden ginkgoes, stopping at last beneath the mammoth green canopy of an ancient camphor, its boughs a haven for numerous plants and creatures.

The son of peasant farmers in Rajastan, India, Satish Kumar has been walking much of his life. At the age of nine he renounced the world to become a wandering Jain monk. At eighteen, inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s call for a united spiritual and social life, he escaped the restrictive monastic order and joined Vinoba Bhave’s traveling movement for land reform, learning firsthand to persuade wealthy landowners to give ‘untouchable’ harijans fertile acres of their own. Later, moved by 90-year-old Bertrand Russell’s prison cell protest against nuclear weapons, Kumar and a friend made an 8000-mile peace pilgrimage on foot, without a penny or food supplies, from Gandhi’s grave in Delhi to the nuclear capitals of Moscow, Paris, London and Washington, D.C., an epic journey movingly recounted in his autobiography No Destination. U.S. edition: Path Without Destination (Eagle Brook)

Ultimately settling in Devon, England, Kumar became editor of Resurgence, an influential bi-monthly magazine exploring traditional cultures, spirituality and ecological thinking. He also cofounded Schumacher College, an international center for holistic learning where he serves as director of programs.

Like his mentors Gandhi and Vinoba, Satish Kumar is a deeply contemplative man of action; his life has been spent, not saved. To talk with Kumar is both calming and exhilarating. One cloudless morning in December of 1999, over cups of tea in the home of Kyoto Journal founding editor John Einarsen, Kumar answered questions from Einarsen, KJ associate editor Stewart Wachs, and Lye Tuck-Po, a Malaysian postdoctoral fellow who studies indigenous cultures at Kyoto University.

John Einarsen: You have said that the first Western millennium was a millennium for God, the second a human millennium, and that the third will be the millennium of nature. You speak of a “reverential ecology” and contrast it to “deep ecology” and other ecologies. What do you mean by this?

Satish Kumar: At the moment, even our environmental movement is very much working on a reductionist principle. They often take one single issue: global warming, recycling, organic farming, whole foods or whole health. Whatever it is, they generally say we must protect nature, that if we don’t, it will damage human health and well-being, the human future. All of this single-issue-oriented, human-centered thinking I call utilitarian ecology. You look at a tree and say we must take care of this, plant more trees like it, because this tree is useful: It will give us wood. It will give us oxygen. It will give us beauty.

In this world large numbers of people are still religious, whereas the environmental movement is generally rather rational, intellectual, we can almost say atheistic. They don’t often consider the divine, sacred, spiritual dimension of our existence. But whether you are a Taoist or Shintoist, a Buddhist, Jain, Hindu or Christian, a Jew or a Muslim, whatever you are, the majority of people are still religious. I would like to connect this spiritual dimension with the ecological dimension. I call this reverential ecology. I would say that the tree is good in itself, and whether it is useful to humans or not doesn’t matter because the tree is sacred, a divine presence. That’s a kind of Hindu idea, that nature itself is divine. There is a difference between considering the divine in nature and nature as divine, nature as totally good in itself. You develop a reverence for trees, for forests, reverence for rivers and for mountains, reverence for birds, animals, insects. And all of that reverence for life becomes the basis of our environmental thinking. Whatever your religious tradition, reverence for life is common to all, and when we appeal to people’s deeper heart, rather than just their physical needs, that is reverential ecology.

Stewart Wachs: But how do we speak to religious Christians, for example, who believe because of scripture that mankind should have dominion over the planet?

The idea of dominion is only one way of expressing the Bible’s teachings in English. Many Christian environmentalists say the idea that human beings are in charge of nature is the wrong interpretation. Now sometimes people ask me, why do you have to coin the term “reverential ecology,” because “deep ecology” falls into the same category. And I have tremendous respect for [deep ecology proponent] Arne Naess.* He was very much influenced by India, by Gandhi and Spinoza, and he’s a great philosopher. He’s a good friend of mine. I do believe deep ecology is much closer to reverential ecology than any other, however the word ‘deep’ for me is not quite enough. You can be deep, yet be in a deep hole. You can be deep and yet be reductionist. Deep doesn’t always mean “good.”

Descartes was a very deep thinker, and yet the way he thought was very utilitarian. Descartes’ famous dictum, “I think, therefore I am,” is based on dualism, individualism, isolationism: I, ego-centered, think, and so everything is in my thought, and therefore I am. Whereas reverential ecology says that we exist in relationship: The tree is, therefore I am. You are, therefore I am. Earth is, therefore I am. Food is coming from the Earth giving me nourishment, therefore I am. My parents gave me birth, therefore I am. My teachers, starting from the Buddha to Mahavir, a Jain teacher, to Jesus Christ and Mohammed, and Tolstoy and Gandhi, and St. Francis and umpteen others gave me teachings, therefore I am. All the music of Beethoven and Bach, and the art of Van Gogh and Vermeer and so on. So, “you are, therefore I am” is the dictum of reverential ecology, whereas “I think, therefore I am” is the dictum of utilitarian, dualistic and anthropocentric ecology.

JE: If you have a culture whose core principle is reverential ecology, what kind of science would there be?

We will observe nature more like James Lovelock, who observes not as if it were an object separate from the observer. We will observe nature as we are nature. The utilitarian scientific split will be diminished. Lovelock developed the Gaia hypothesis in which the whole Earth is one living organism, each and every bit, worms, fungi and bacteria, the smallest living organisms.

And we will say, I will never be able to understand the entire system. If you go into the rainforest, the deeper you go the more forest there is, the more mystery. You cannot say that we have reached the forest and now know the rainforest. The deeper you go, the more there is to understand. And yet when you study a particular monkey or insect, you’ll say I am only trying to understand a little bit, but I will never be able to unlock everything. You have reverence, an awestruck state of being, and not necessarily everything explained.

JE: Arne Naess once said that perhaps mountains should be left unclimbed, because if we know people have been up them, they lose their magic or power. Can human beings really learn to let things be, or is it just in our nature?

It’s not in our nature. It is the conditioning of the last 500 years. That’s why I say the human millennium. Particularly since the Renaissance we have been developing and conditioning our minds to think we have to find out everything. The idea of “no limit” is bringing us to a kind of abyss, a crisis.

SW: Yet some would say the very idea of no limits has enabled quantum physics to discover the unity of the universe, and that if we had limited physics, we might not have come upon this incredible discovery.

But spiritual and the holistic philosophers did know this. If you take Hindu philosophers and Taoist philosophers, the unity of the universe had already been discovered. Science only discovered it in a slightly different way, but nothing new. There are limits within an unlimited universe.

SW: So it’s like someone who conducts a survey only to discover something everyone already knew?

Yes, and that’s what science does all the time. Recently, there was a study in England where they discovered that those who pray are more able to heal themselves, easier and quicker, than those who don’t, and they studied thousands of people to find this out. People have known this for thousands of years, and that is why prayer was invented. It’s healing. It puts you in touch with the universe. It creates a kind of relationship: I’m not alone. “I think, therefore I am” is not right. I exist in relationship. And prayer is the technology, the methodology of practicing that relationship. Science reinvents the wheel all the time and discovers that which has been known for centuries, so I don’t think that knowing our limits will necessarily stop you from realization of the unlimited. There is no limit to knowledge, but there are limits to economic growth.

The more you study with humility, the more you realize the unity of the world, its mystery, and yet you will have further knowledge. There is nothing wrong with knowledge. It’s a question of knowledge with ignorance. If you go only for ignorance, you are lost. If you go only for scientific knowledge, you are lost. There is this interplay between knowledge and ignorance. It’s almost like a dance, like silence and speech. And in that dance you find relationship and you arrive at reverential ecology.

JE: What would education be like in reverential ecology?

At the moment our education is very formalized and intellectualized, very academic. We learn everything from books, and now from computer screens. Education based in reverential ecology is experience-based, so if you want to learn about the ocean you won’t start from a book. You’ll take children to the ocean and say, go dive in the ocean, and observe what is in it. Walk and see and smell the organisms around it. And once you have experienced this, you come back to the classroom and the teacher says, well you discovered this, but such and such a person before you discovered that, and you can bring out some books, some computer programs, and see what other people have to say about oceans. Afterwards you go back into the ocean and compare what you have learned from your own experience, then from books and the computer, and then come back to your experience. So you learn much more directly.

SW: This seems also to imply that education should not be, as it is here in Japan, so centralized, because clearly not everyone lives by the ocean. Some live near mountains, some in urban centers. Are you implying that this kind of experiential education should be tailored to local conditions?

Absolutely. I gave the ocean as an example only to illustrate the point. It could be trees or animals, insects, worms, mountains, or rivers. It could be just rocks, or grasses. But it’s being outdoors in nature, letting all your senses experience: your eyes, ears, touch, smell, taste, thoughts, your consciousness. So time, space and consciousness are included in a more holistic and more reverential education. Whereas in the formal and reductionist education you are using very few of your senses, mostly your intellect.

Holistic education with reverence for life would include a large emphasis on practical skills for life. So, instead of only studying the ocean, mountain, or fungi as an observer, detached, you are studying nature as part of your life relationship. You dig the soil and plant trees, vegetables and flowers, and you learn to grow them — learn while you are doing. So you don’t learn just theory, but learn through practice. In the Western way of thinking we say theory and practice. In my way of thinking it should be practice and theory. In Sanskrit the words are achar, vichar. Achar means practice. Vichar means theory. Practice must come first and theory must follow. Whereas in Western education theory comes first, then practice, if at all. And you know, the head of any monastic order in India will be called Acharya, like Vinoba Bhave was Acharya Vinoba, and my guru was called Acharya. This means one who practices is the head, not the intellectual, not the person who has the brain.

So you take children into the garden and put them to work and while they garden they are learning. It’s not as if they are missing a lesson. Growing in the garden is the lesson. Then you send them to the kitchen and say, now find out the knowledge of our food by cooking. And cooking, too, is not by itself a separate thing. It is to share. So to learn about community is to cook in the school. So holistic education is: growing, cooking, sharing, community, building together.

JE: I am realizing more and more that education is so goal-oriented that we are forgetting to enjoy the process.

This separation of goal and process is again the dualistic school of thought. In the holistic process everything is means and ends at the same time. There is no separation. Mahatma Gandhi said the means are your ends. You cannot control the ends, and therefore the ends cannot justify the means. Means must be compatible with your ends. Reverential ecology teaches us that your means and your process are your way of being. That’s why nonviolence is not a theory, not a tactic or strategy. Nonviolence is a way of being, a way of life. You are not using nonviolence, even to achieve your good ends, but you are living nonviolence. Whatever work you are involved in, whether it is independence or civil rights or the ecology movement, nonviolence would be implicitly present there. That is why education is not to achieve but to fulfill, to discover who you are. So education is not achieved when you have completed college. It is happening every moment. The Western system has emphasized the achievement, the success. And I say to students, seek not success, but seek fulfillment.

Lye Tuck-Po: All of this is a great philosophy for individuals, and certainly in my own research I look at the merits of practice-based versus institutional learning, but it’s hard to see how it could work for a big community. Let’s say London.

Even now, at the end of a very urbanized and industrialized century, 75 percent of the world’s people aren’t living in big cities like London. They are living in small communities. So first, if you would like to develop a reverential ecology, try not to idealize urban, industrial, mega-cities, but think in terms of communities which are smaller, and protect them. Don’t think that small communities are backward, that they are finished and we have to urbanize every bit of the world into Tokyo, New York or London. That is a misguided notion. Most people still live in villages in China, India, South America, Africa, Russia, the Middle East. That’s one answer, that we mustn’t idealize big cities. We must acknowledge that building large cities was a big mistake of the 20th century. You won’t be developing holistic and reverential ecology if you say we have to find a solution for people in urban centers, as if the majority of people are already there. Accept that this kind of industrialization, urbanization, is a step in the wrong direction. We must create a new economic system where people who are already in rural areas will stay on the land, stay with their crafts, work to preserve local communities and not become swallowed by a globalized, urbanized economic system.

The second answer would be that even in cities we must create urban farms and urban communities. I went to Nara. Everywhere you see deer. Why not in Kyoto? We must bring nature into the cities. Nature and culture are not enemies. They should be seen as two sides of the same coin. Cities must be naturalized, and gardens, animals and farms should be brought into them, so they don’t become soulless, concrete jungles. We need to admit we have taken a wrong direction, and that we have to right it.

SW: Johan Galtung says we shouldn’t do anything we can’t undo. Are you saying it’s time to undo the cities?

Yes, undo the cities. Make smaller neighborhoods, and each as far as possible self-contained, with their own hospital, schools, and markets, so people living there can walk to all of their basic necessities. That would be my idea of cities – a honeycomb of smaller neighborhoods, each self-contained. A few things you can’t afford in your neighborhood, like a concert hall, or a Noh theater, you can go farther afield once in a while to see a play or a film, but everyday needs should be met in each neighborhood.

LT: That is already a trend in many Western cities, to decentralize and create more tangible neighborhoods. I believe in what you are saying, a reverential kind of education, but policy does not change at the individual level. If you want to inculcate these values you have to infiltrate government thinking, put it into written policy and laws. That’s why I was thinking of the larger scale. How do you change that?

Larger scale begins with smaller scale. This large tree in front of you, a hundred feet tall, started with one small seed. So the big is already embodied in the small. The mass society we have now has been built over hundreds of years. You cannot change it overnight. You have to start small examples, small experiments, see where they go wrong, where they go right. When you have many such successful experiments people will say, this is working. There is more vision here. More community, more humanity. There is more compassion, more joy and pleasure. People will see it. Then they will vote for people able to implement these ideas on a larger scale. Don’t worry about large scale at this moment. Our movement is too small to think that we will go and change Tokyo tomorrow.

LT: But some of us do want to change Tokyo.

No, I think that is wrong. Our environmental movement should be humble, and we shouldn’t think we can change the government in Tokyo or London overnight. We have to start where we are. Build from below, rather than try to impose from above. Small, environmentally-sound, ecologically-sustainable, reverential ecology-based projects – schools, shops, farms, gardens, crafts, even a small university. . . That’s why I’m involved with Schumacher College, a small educational project that has been going for ten years. Now people come and say I’d like to start a Schumacher College in my country. I say, start! But start small and with humility.

I know this is a new and a small movement, that we must make strides towards reverential ecology, rather than think that we know the answers, that we have got the truth, and now why doesn’t the whole world follow us? The environmental movement doesn’t have all the answers. So we are still honestly searching, and lots of the movement is just sort of a waffle. More printed words, more talks, and very few real, practical experiments and living examples which people can go and see and be impressed by.

SW: What are the best ones you know of?

Adam Wolpert has got a very good center [Occidental Art & Ecology Center, California]. Cathrine Sneed has a project in the county jail in San Francisco where she has started to teach prisoners gardening as a way of reform. They started small and now have something like ten acres. I went to see it, and there were perhaps a hundred prisoners working on this garden. Wonderful tomatoes and beans, and peas and lettuce, everything is growing, and they are supplying them to some restaurants in the Bay Area.

SW: Are they also eating the produce themselves?

Yes, they feed themselves. Similarly Schumacher College is an example of the kind of education where living and learning are a continuum. Everybody starts the day with a period of meditation, because unless you can be calm and centered within yourself, you cannot influence the outside. We always want to change others, yet never want to change ourselves!

Then we have a period of work. All members cook, clean, garden, wash up, do domestic chores. They are not just engaged intellectually, but physically and emotionally. They work with other people of different nationalities. There is a sense of community. Then, at ten o’clock, when they have done their domestic work as a way of learning, they come to the classroom for intellectual learning. And whether they learn with James Lovelock, Fritjof Capra, James Hillman, Theodore Roszak, Vandana Shiva or Arne Naess, whoever the great teacher is, participants learn with them. In the afternoon, we go out in nature – to the sea, the gardens, field trips. And then in the evening we engage in music and dance. So your emotional, intellectual, and imaginative qualities are all catered to.

Every school could follow the Schumacher principle: Small is beautiful. Never think that things of quality happen on a large scale. We must shift from quantitative thinking to qualitative thinking. Don’t worry about the big, worry about quality. That’s why there is a difference between “standard of living” and “quality of life.” A standard of living is quantitative: How much do you have? How many houses, and how big? How many cars? In qualitative thinking you ask: Is it good? For example, you might have lots of food in the house, but it’s all junk food. What’s the good of that living standard? But what if you have two cabbages, and they are organically grown, fresh, picked today? You cook and serve them with love and share in community. That, to me, is quality. So think small.

LT: Where does reverential ecology get its intellectual roots from?

Oh, its intellectual roots are very old.

LT: That’s what I was about to say. The hunter-gatherers I study have a lot of these same intuitions and feelings. They don’t put it in these terms, though.

The thing is, the world moves in cycles. Time is not a linear but a cyclical process. And in that cycle things move backwards and forwards. Reverential ecology comes from old, old traditions – Native Americans, or the Australian Aboriginal people, who had this idea of Dreamtime. I went to Australia and was very inspired by the Aboriginal people. They said that fifty percent of them are artists. Which other community can claim this? Fifty percent of people in Japan may be able to manipulate computers. . .

LT: That’s because in such communities they haven’t disengaged the role of the artist from the rest of society. They don’t have artists with a capital ‘A.’

Yes, so that is our inspiration. I was saying that this moves in cycles, and that the Christian millennium, the first millennium, was the millennium of God, where we thought that the world is something dirty. It should be discarded. The world is a trap. Sinful. And so everything worldly was bad, and what was godly was good. And therefore you think of the other world, the day of judgment and how God will send you into heaven. So that was the millennium of God.

Then we moved away from that because it was too frustrating and otherworldly. We wanted to enjoy the world, to take pleasure in it. So we discarded God altogether, made everything human-centered. This started with Christians like St. Augustine, and then also the Age of Enlightenment and the Age of Reason. We moved on to the Age of Technology and science, into the industrial revolution and information technology. Francis Bacon said, “Nature is to be conquered.” Descartes said, “Nature, mind, and matter are separate.” Mind is where we have to concentrate. All that was part of the human millennium. Humans in charge.

LT: That’s only European history.

But that is the dominant history in the world today: the colonialism, imperialism, globalization, industrialism, scientism, centralization, world trade, GATT, IMF. Wherever you look, the dominant trend in the world is Western thinking. And the Third World – Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, China, India – all these countries are trying to follow the Western path. And they say their countries are backward. We are all underdeveloped or undeveloped. India is undeveloped! All our culture of the Vedas, Upanishads, Mahabarata, Ramayana, Kathak dance, sitar music, Sanskrit language? Everything is backward! We send our children to Oxford, to Harvard, to Kyoto, to big Western universities and educate them in modern science, computer information technology. We think our cultures are not good enough. We are dominated by the Western way. A technological hurricane of globalization is sweeping the world.

LT: But we see a counter-trend, and to me it’s equally dangerous, in which you have Asian leaders proclaiming “Asian values” as though there is something ineffable which cuts across cultural boundaries, national boundaries, and it’s seen as something that Asia has which the West does not, and by that same reasoning the West shouldn’t impose its ideals of human rights on us Asians with our Asian values.

I’m more keen on thinking in terms of local values than Asian values. Each locality, each human community has developed according to their geographical, climatic, cultural conditions. Each has some unique gift to offer the world. A different kind of dance, different music, a different way of painting. So, I talk about local values rather than Asian values, European values, Indian values, Chinese values – these are too monolithic.

LT: Technological thinking is sweeping the world. But I also see this counter-trend, where people are trying to assume that there is something Asian which is superior to the Western. . .

Two wrongs don’t make a right. I come from Asia. I come from India, but there is no one monolithic Asian culture I know of. There are many Asian values, many local cultures. Even within India there are many distinct cultures, for example the Punjab – it has different food, clothing, language, different traditions, different everything! So you can’t even say Indian values, never mind Asian values.

SW: Is it a kind of mental laziness, then, to think of values in such a sweeping generalization?

It is. We always want to use labels which are big and sound good, but there is no substance to them, so “Asian values” is hollow in the same way as “European,” or “American” or “globalization.” To create a reverential, ecological worldview, you have to think local, decentralized, biodiversity. You must have a variety of values. There is no one blanket world system which everybody should accept. And you have to allow a tremendous amount of cultural diversity.

LT: How does this message go down with the Schumacher students, and while I’m on that issue, what kind of people attend Schumacher College?

First of all, we run three-week courses. That makes it easy for people to come because they don’t have to give a whole year or so. And at any one time there are only 25 people at most. Whatever the demand, we never accept more because there is a kind of cohesion, a sense of community in that number. They all come to know each other, find out about their backgrounds, their projects, and learn from each other. In the last ten years we have had people come from 75 different countries. Our main idea is to experiment with a more reverential and holistic approach to learning. Quite often people say, although I came because of a famous teacher, I learned more from the way life and education at Schumacher College are organized.

So they come from all over the world, and all ages from 20 to 70. The only thing students need is a good knowledge of English, because they are coming from so many languages that we can’t afford to translate. But otherwise there is no barrier. You don’t have to have an MA or Ph.D., because we try to bring good teachers who are able to teach in a simple way. E. F. Schumacher used to say, “Any fool can make things complicated, but it requires a genius to make things simple.” So however wonderful a teacher you may be, we require you to speak not simplistically, but simply. Instead of academic jargon, education is conducted in language accessible to ordinary citizens from any country.

Also, we try to provide a place where these great thinkers and activists from around the world can come and teach. They come, they relax, they bring their families. Fritjof Capra has been there five or six times. He comes with his wife and daughter and stays for four weeks. He wrote his book, Web of Life, at Schumacher College, because all of his students were giving him input.

So these teachers have a place, not only to write but to communicate face-to-face. In person. There is a different quality in this kind of learning. When you write a book it is, I say, “broadcast.” You print 20,000 copies and they go all over the world. But when you are with 25 people in a place for three weeks, and you have breakfast with them, then go walking together, you rub shoulder to shoulder. That is “deepcast.” You have such intimate communication that you go away with friendships that last. Then you stay in touch through letters and e-mail and so on. So our teachers benefit as much as our students do. They go away nourished and fulfilled because of this human quality, and human input.

LT: Do you track the students after they go home? What do they do? How do they put these principles into practice?

Quite a large number of our students come from schools and universities. And I’ve seen many of them from America, South Africa, India, developing new syllabuses and curriculums which are more holistic and interconnected, more integral. So that’s one benefit. Then there are other students who start new projects, like one in Australia who went back and created a center for teaching permaculture. So they teach, and start many different kinds of new projects.

SW: You said they come from 75 countries. That means some are coming from poor countries. Given the imbalance of currencies in the world, it must be terribly difficult for some people to make their way to Devon, England and cover their expenses even for three weeks. How is this achieved?

We have a strong policy of giving scholarships to people from non-industrialized countries. And we have raised a scholarship fund from a number of foundations.We make sure that the deserving students from India, Africa, South America, or anywhere where exchange rates make it unaffordable to come, receive full scholarships. Also, people from Western countries, if they are poor, but need and deserve to come, then we provide them some scholarships as well.

SW: How did you manage to get the word out around the world?

We have a very wide network. First of all, Resurgence magazine has a circulation of 10,000 and each copy must be read by three, four or five people, particularly in non-industrialized countries, where they share it more widely. Then we have been very lucky to get good articles in newspapers and magazines in India, Africa, and Europe. And we have developed at Schumacher over ten years a very large mailing list of people worldwide, in about 100 countries. And we have a Website, and so on. So, altogether we are able to reach a very wide audience.

LT: It’s impressive, because I seem to have known about Schumacher College as long as I can remember, without quite knowing how. . .

Word of mouth is very effective. People depend too much on technological communication. Schumacher College is on the grapevine. If it’s a good quality center people will somehow come to know about it.

LT: I want to shift the topic slightly. One problem of getting any sort of consensus on the environment is that everybody has different notions of what “sustainable development” is and how to achieve it. We cannot work together, because sometimes these are inconsistent. What do you say to that?

First of all, the word “sustainable” has been hijacked by the establishment. Even the government is talking about sustainable development; therefore the word has become suspect and meaningless, because once you start to use the word in such a loose way it loses its power. Second, “sustainable” is a sort of negative and pessimistic word. I don’t particularly like it. I want to have something which is good. Whether it is sustainable or unsustainable is not really the primary issue. The issue is, what is good? And that’s why I call it reverential development and reverential ecology, rather than sustainable ecology. So I would urge our environmental movement to use the word sustainable as little as possible. Don’t use it, because it has already been corrupted by the establishment. But having said that, within the movement, there will always be differences of opinion, and that should not be discouraged. It should be encouraged and appreciated. Differences should be celebrated, because if you have ten thinkers and ten activists working ten different ways, that is better than everyone following just one leader in a herd. A diversity of approaches and experiments is always appreciated. But we mustn’t quarrel. We mustn’t say, my approach is better than yours.

LT: But those of us who work with indigenous peoples around the world see some danger in this. For example, the animal rights movement in the West says, “Ban hunting, ban whaling, ban all animal killing totally.” But there are people who hunt and whale for sustainable livelihoods.

There are no absolute truths, no final answers. When indigenous cultures hunt and gather on a small scale, in a very ecologically sustainable way (although I am a vegetarian) I can totally understand and appreciate their traditional way of living. Ecological problems don’t arise because of small-scale hunting and gathering. Problems arise because of the mass scale of industrial methods we use for farming. For example, gathering fish using industrial ships with factories inside, a sort of vacuum cleaner that sweeps the sea and only uses five or ten percent of their catch, and then exports it around the world. That kind of factory farming on a massive scale is wrong. The real problem is when the meat business becomes a large, profit-making world trade. That’s where the effort of the animal rights movement should go. For example, in England we had the BSE problem, “mad cow disease.” And four million cows were slaughtered in two months. That’s the cruelty of humans. It’s almost like an animal Holocaust. That is where compassion and animals rights should come in.

The environmental movement also has to be self-critical and on guard. That’s why I say much of the movement is following the methods of reductionist science. We need to move towards a more reverential ecology. The environmental movement is becoming achievement oriented, and not method or means oriented. And means is where the real test is. If your means are right, then your ends will automatically be right. But if you focus on achievement and success, that’s a very materialistic and utilitarian approach.

JE: Many people have left a record of mystical experience. How do you explain such experiences?

For me, whether it is St. Francis, who was a mystic, or Rumi and Kabir, who were mystic poets, and even in our time somebody like Rabindranath Tagore, who was a mystical poet and writer, all of these people have found that their mystical experience goes beyond language. St. Francis wrote beautiful prayers like “Brother Sun” and “Sister Moon,” but his mystical experience goes beyond them, and that comes from an affinity, an infinite connectedness with the natural world. Mysticism and nature cannot be separated. Divine nature is the source of mysticism. Once you can see the divine in the tree, you are awestruck.

And this is even true in science: I know James Lovelock personally, and I would say – perhaps he would not like the label — that he is almost a mystic scientist. He has forty acres of forest around his house which he has protected, and he goes walking there every day. He is eighty, and yet he walks faster than me. He walks on the seacoast and on Dartmoor, and he is awestruck. That’s where the hypothesis of Gaia came from. Not in scientific laboratories. He justified and explained it in a scientific way, because he is a chemist and a scientist. But his insight of Gaia was intuitive and mystical. So, we have lost mystical experience because we have lost our close, intimate, direct, everyday connection with nature.

My mother used to say that nature is the greatest teacher, even greater than the Buddha himself, because Buddha also learned his compassion, his generosity from nature. Buddha got his enlightenment sitting under a tree. Why we don’t get enlightenment, mystical experience, or intuitive connection, is that we don’t sit under a tree long enough. That, to me, is the source of mystical experience. We always hanker back to all these mystics we don’t have nowadays because we are so confined with indoor life. We sit in the house, go out and sit in the car, and then get out of the car in the parking lot and sit in the office under artificial lights, and then we go out and shop. Everything man-made, artificial and contrived. How do you expect human beings to have mystical experience in this day and age? No possibility! This is the real thing we have lost. If you want mystical connection and experience, then go into wilderness for weeks, and you will find it.

SW: Vinoba Bhave not only had to persuade the Indian landowners to give away land, but also convince the untouchables to take the land. They believed it was their lot in life to settle for what little they had because of karma. The people you’ve just described, who don’t experience nature, are in a sense landless. It’s not a question of owning, but a matter of not experiencing. Should someone perhaps be walking through cities like Los Angeles, trying to reconnect people to the land?

Why not? I think we need to have walkers or eco-warriors who would say, come on, we are going to walk in nature; organize or invite people and say, let’s take very little, and just go. That would be a wonderful thing. And you know, Vinoba’s land gift became famous. He was walking, not going by jeep or by car. I was walking with him, and he walked 100,000 miles. He would sit on the hillside, by the lake, and would give his teachings, his concerns. He would communicate in nature, before dawn, or just at dawn. I would say that if anyone is able to lead people out of their boxes and into nature, that would be a great healing for many of us. A great healing.

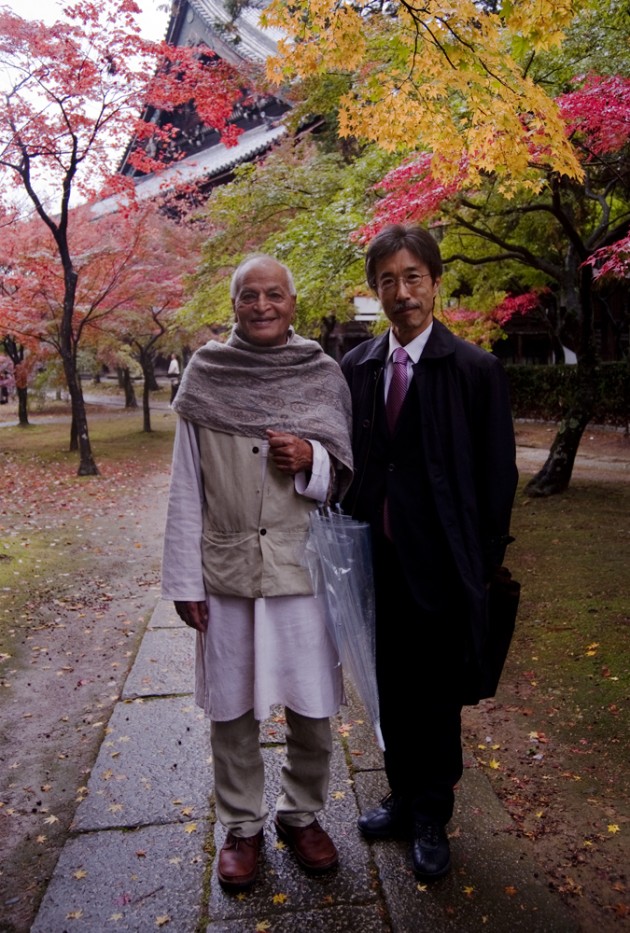

Photo of Satish Kumar and Terry Futaba at Shinnyodo Temple by John Einarsen