[G]wendolyn Hoeffel was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1942. The daughter of a pediatrician and a nurse, she attended a Catholic high school and college. After graduation, in 1964, she came to Japan as a volunteer missionary. She entered the Society of the Sacred Heart and eventually took her vows as a nun — a decision she had originally made, she says, at the age of fifteen. With the exception of two periods in the United States to pursue Masters degrees in Religious Education and Clinical Pastoral Education, she has spent the last 50 years in Japan.

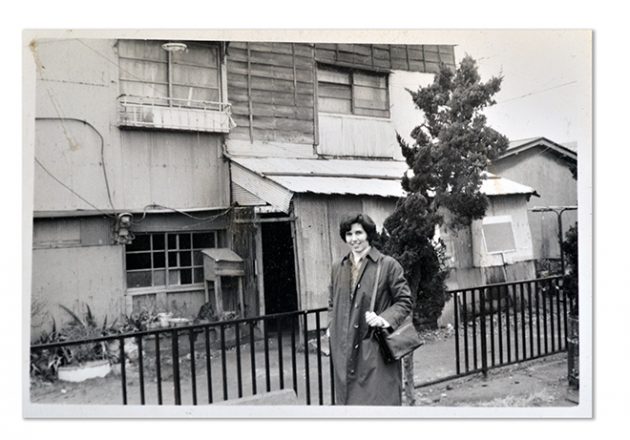

From 1960s to the 1980s, Gwendolyn taught elementary school at the prestigious International School of the Sacred Heart in Tokyo, where she eventually became principal of the Kindergarten through 4th grade section. In the interim, she spent two years in Nagoya establishing a Catholic foundation whose mission was to serve the poor. In 1993, she returned to Nagoya for good and has devoted the last two decades working with immigrants, refugees, victims of domestic violence, and others in need of support.

Nagano-based writer Winnie Bird first met Gwen in 2005 — the year she moved to Japan. They have remained friends ever since.

What does Japan mean to you? I know it’s a big question.

It’s immense. And what it means to me now and what it meant to me 50 years ago has evolved. I came as a volunteer missionary right after college. I was thinking of entering religious life, but I was also very interested in missionary work — going to another country, having experiences, and sharing Christianity — to share the love of God, honestly speaking. So I applied for a volunteer position. Having studied Spanish, I thought I’d go to a South American country. I left it to the powers to be, our Superior General in Rome, and they sent me to Japan.

I took off in September 1964 and landed in Tokyo to begin teaching second grade a week later at our international school — with no qualifications. By complete luck, I’d arrived in Japan during the year of the Olympics. Tokyo was booming and bustling and primping itself with new subways and buildings.

So there I was thinking: “Okay now, I’m in Japan. I want to know Japan and to be a part of Japan. But I’m at the International School. This is fine too, though. There are fifty nations represented at the school, and I’ve always wanted to have a big international family.” I was very much influenced and broadened by the experience, and I became very cosmopolitan. I felt, “Here I am in the little island of Japan and the whole world is before me.”

I was introduced to a lot of Japanese students in the university. One particular young woman said she’d like to host one of the new teachers — me. [She] is still a friend today. She introduced me to Japanese culture and brought me to her home. I had all kinds of experiences that, as a foreigner, you didn’t used to be able to have because the Japanese were more closed then than they are today.

When I think back to those first years, what really drew me into Japan was the unity with nature. In everything — food, house décor, the kimono, and ikebana. Everything is so one with the seasons, and the seasons are so beautiful. Also, that particular friend and a lot of Japanese people I met [said] “You’re not the typical American. You’re one of us. You’re like us.”

What did they mean by that?

More reserved and quiet. I can’t say I was refined. But they thought an American was an aggressive, loud, outgoing type person. I tend to be shy. And so our ki — our hearts, our minds — connected. They taught me that — you fit in with us.

I’ve often felt like I don’t fit in here because I’m outspoken. You didn’t feel that kind of clash?

Not at that time, not at all. Actually, when I was in high school, I was reprimanded because I tended to be reserved and quiet. That was what attracted me to religious life and to contemplation. That’s where I can spend my time very happily.

So, in one way, I went [to Japan] saying I’m going to bring love, peace and the freedom of Jesus to these people who are in the valley of darkness. And, in 1964, they were still coming out of the postwar rebuilding period. It was always in conversations. Among many, there was great respect for America because they didn’t crush the Japanese after the surrender. A lot of people really were grateful — almost too much I felt.

I wanted to ask you about that. Even for me coming here in 2005 I thought a lot about Hiroshima and Nagasaki. What’s it going to be like for me to come as an American, with that past? For you it was so much closer. How did you feel coming to Japan as an American less than two decades after the end of the war?

There were a lot of complex feelings in that regard. I had an uncle who was a prisoner of war. The year I graduated, 1964, my sister got married. This uncle was my godfather, although he didn’t know it for about two years because he’d been a prisoner of war when I was born. He had a bit to drink at the reception, and while we were dancing he said, “How can you go to Japan, our enemy?”

But I said now we’re at peace, now we’ve got to rebuild, live and forgive and be together. That’s naïve — I did not experience the war, although I heard stories about it. But when you’re young and idealistic and haven’t experienced so many horrendous things. . . again, maybe this is my personality, but I just didn’t want to carry grudges and hatreds from the past.

Did you feel this was possible at that time?

Yes. And that was largely because of the welcome I received and the hospitality and graciousness of the Japanese. I realize now that I was with educated, cultured people — our students and alumni. A lot of them had lived abroad. They all spoke impeccable English. They were alumni at the Sacred Heart. The sisters had come in 1908, had gone through the war with them, and had been with them in the internment camps.

There must have been American sisters in Japan during the war. What side were they on? What happened with them?

Just last week, I was in Tokyo working with our archivist. She’s been putting together materials about the first missionaries, and she had a number of letters from Australian and American sisters who were interned in Kobe, and then in Nagasaki. The spirit was one of such kindness. They would say how kind the guards were to them, how kind this person was in helping them do this or that.

The sisters were put in camps by the Japanese military just because they were American?

Yes. We have all these pictures of them in their habits. They somehow kept life going. There were also a lot of Protestant missionaries. They formed a community, cooperated with each other, and worked things out among themselves. In Nagasaki, they were way up the hill from the center of city. When the bomb fell, all the windows shattered, and many of them got hurt.

Then they became hibakusha too?

Yes, but they were far enough away that they weren’t sickened by radiation.

Then after that, they came back to the people who had put them in prison, and went back to serving society.

Right. A few went back to the United States and then came back to Japan later. I think it was partly their faith, their education, and, really, their respect for individual Japanese. They were dealing with ex-soldiers and commanders, but one-to-one.

Those were some of your first impressions. Since then, has your understanding of Japan, or what it means to you, changed?

As the years passed, I was very aware of Japan becoming more prosperous, more accepting of Western values and customs, which has been detrimental in certain ways. Obviously we have to move on, and the traditional, gracious way of living that I experienced in 1964 is going to move on. But since then, we’ve seen the breakup of the family because of children having to study, study, study. The kyoiku mama pushing her child to get into a good school. That competition — push, push, push. The husband — work, work, work. All for material benefits and reputation. The kind, gentle, gracious lifestyle fell apart because of competition and the outside world coming in. It affected Japan even to the point of physical health. You started to see children getting fat from Kentucky Fried Chicken and McDonald’s, or not sitting down and having a decent meal around a family table.

Almost 20 years ago, my old friend from Tokyo came back from abroad. She said she felt for her husband, because he was senior in his company and young people didn’t have the same kind of respect for the senior members any more.

When you first arrived, did this extreme hierarchy based on age and position feel constricting and oppressive? Or did you feel it was a positive part of society?

Obviously the democratic, more liberal part of me thought it was a bit much. On the other hand, I was in a hierarchical church and society and I was a docile, naive person. During the 1960s and 70s, with all the demonstrations, things changed. And with Vatican Two [the Second Vatican Council, which took place from 1962 through 1965 and modernized practices within the Catholic church] religious life just went topsy-turvy. But I did grow up and join the real world. I saw things have to change.

With Vatican Two, there was the call for religious orders to return to their original visions. For us here in Japan, the way into people’s lives was through education. The church had come originally to work among the poor. It couldn’t get rooted, so it went to the intelligentsia to get established, and that’s who welcomed us. But the original vision of our foundress was that where we had a paying school we’d now have a non-paying school. So for us, Vatican Two was a chance to reestablish that balance between the education of the more wealthy and serving the poor.

We were invited to Nagoya by a group of Augustinians, to the Minato-ku area which is the poor world of Nagoya where the factory, dock, and other low-paid workers live. Leaving Tokyo and Sacred Heart School life in 1971-1972 to start a free school in Nagoya showed me a whole other Japan. When I came back in 1993, there was a new wave of immigrants from the Philippines, China, and South America taking these dirty and dangerous jobs. In Tokyo, Osaka, and Sapporo where we have our schools, we’re not aware of this “backbone of the country” at work. These people are doing these basic jobs so the rest of us can have comfortable lives.

The immigrants you work with, are there any issues you feel they are facing not just because they’re poor but, specifically, because they’re immigrants?

Some people don’t keep their visa in order. They don’t get the right papers out of basic ignorance, not having the courage to go to a ward office, going and then being rejected, or because the officials don’t try to understand. They just, you know, try to get rid of them.

You sometimes go with people to these offices. Is this something you’ve observed firsthand?

Absolutely. Respect towards Americans is still present among officials, versus towards a Filipina or Chinese or South American. Somehow, I can make a difference because I’m American. Once, when I was advocating for someone, the official said, “You’re trying so hard, I feel I must do my part.” I was really touched by that. People do have hearts. People are good. You just have draw out the human, compassionate part of them.

I imagine doing that kind of work it would be easy to get disillusioned. Yet you seem to hold onto that faith.

I also recognize that for people in immigration or at the ward office, they’re doing their job as it is identified for them to do within this box. It’s hard sometimes to break through. I say to people, just keep asking. If you don’t show up, it’s better for those officials. They don’t see or hear you anymore. You just have to keep hacking away at the system. As you keep going back, people get kind of friendly, kind of human.

Over the past eight years you’ve worked more and more with refugees. Is there any specific story that you could share about a refugee you’ve helped?

There are so many! I’ll share one about this young Rwandan man who had his first request to be accepted as a refugee refused. He lost his family in 1993 in the Tutu and Hutsi genocide. He went to stay with an uncle, aunt, and [their] daughter. This uncle was also on the wrong side of the government and once again his family was killed and house burned down.

According to the story, a priest took him in and protected him. Eventually, the priest got him a visa to Japan. The priest sent him off, telling him he’s going to Fukuoka and that a Rwandan would meet him there. So he arrives in Fukuoka, is met, and is taken to Kumamoto to apply for a proper visa. But you can’t change your visa in Japan. You have to go out of the country first.

He was refused. He had to move on. I think he met some Kenyan person who took him to Tokyo. He ended up in Nagoya and became homeless at age 20 or 21. Tomonokai, a Catholic charity where I work, was contacted. A man from Burundi got ahold of us, saying he’d picked up this young fellow and that he’d taken him back to his apartment but couldn’t keep him there. Then, I find out he’s released the Rwandan man back onto the streets. It was Easter Sunday. I said if you can find him, we’ll do something.

How long had he been on the street?

A couple of weeks. He was hungry and sick. One of the priests who works with us had a little house on church property. So we asked him if this young man could stay there until we got him applied at refugee headquarters for funding. I had a fold-up bed, futons and blankets, and was just trying to get him set up, using a little French and English. I took him to immigration to apply for refugee status. We had to get his story written out. Finally, the funds came through, and we got him an apartment. Well, he started doing things for himself. He found a sports center and some Japanese befriended him. He started learning Japanese.

And the government support payments?

The government supports his rent up to 40,000 a month. Food, water and gas and whatever else comes to 45,000 a month. Which isn’t bad but it’s not enough. We really want him to get educated. He’s had his ups and downs, and he’s kind of down right now because his application for refugee status was refused. He was turned down because, for one, he was able to leave his country safely, and two, because there’s no documented proof that his life is imperiled because he’s a Tutsi.

There are still a whole lot of cross-border problems with Congo and militia groups, and with revenge groups. But Japanese government officials say ‘What’s your problem? Everything is fine back there.’ He doesn’t buy that. He doesn’t feel safe at all. He just doesn’t feel he can trust anybody.

Seeing this man’s case and how he’s been rejected, what does that make you think about Japan and it’s responsibility towards other countries?

I have very mixed, and frustrated, feelings about the whole situation. Look at tiny Japan. Sometimes I feel I’m taking up space I shouldn’t be taking up. Compared to the US and Canada taking tens of thousands of refugees, they can’t do that here. But I guess it comes down to xenophobia. “We are Japan, a homogenous country. We don’t need you, we don’t want you. We belong to the UN contract for human rights. We pay a lot of money to the UNHCR so they can’t tell us what to do.” [UNHCR]’s hands are tied — I’ve been told that by UN people. They get a lot of money from Japan.

So they give Japan an easy ride?

Right. They’re not criticizing them, not prodding them to be more open, from what I understand. Japan is very strict on who and when and why it will recognize refugees. They really study things and take a long time to decide. People wait years to be recognized. Their lives are on hold. Sometimes I’d like to say to them, just go home, you’re wasting your life here. But I had one Kashmiri who gave up and went to Pakistan. I spoke with him recently. He’s not safe, but he can’t get out.

So you just try to support people in whatever way you can?

Yes. They need some kind of lifeline, some kind of knowledge that people care. We have food, and can help with their situations. If they go to court, we connect them with lawyers.

Culturally, is there anything you especially like about people’s way of thinking or living here in Japan?

You say “way of thinking.” It seems to me, the longer I’m here the more mysterious it becomes. In terms of the way they view the poor, or foreigners, I don’t particularly appreciate the way people around me think. “They’re lazy, thus they’re poor. What are they doing in our country?” type of comments.

But I think Japanese people are hard on one another too, which causes a lot of friction and unhappiness. It’s the conformity that’s been imposed that I find takes its toll on people’s lives — always having to do as teacher says or as the other does, as society dictates.

You asked for positives and I’m getting negative! I try to avoid the negative because I’m very aware that if I criticize something Japanese . . . well, who am I to do that? I try to be more general. We’re all humans, wherever we are. We come up with the same foibles and problems. So I’ll say gosh, it’s not only Japan, it’s everywhere. But this aspect of Japan is kind of a shame.

It’s interesting that you just said “who am I” to criticize Japan, because now you’ve been here almost 50 years, so by far most of your life has been in Japan. Yet you still feel that you’re not in the same position to make a critique as if you’d been born here.

I think in the past I would have felt that way. In the very beginning, everything in Japan was wonderful. Maybe I was Japanese in my first life! And then, I became more worldly, more wise and informed, and I certainly started critiquing more. Now, I’m feeling more American and that the Japanese are more Japanese — a “ne’er-the-twain-shall-meet” type of thing. That’s fine. But I also feel that we are all one as human beings, and that we’re all interconnected.

When you say, “I feel American,” what does that mean to you?

I think openness and — although this isn’t true for all Americans — trying to think outside the box, daring to be different. A certain freedom. There are things, cultural differences, that have struck me over the years. One example: When somebody trips and falls in public, nobody will go to help. I find myself naturally — as a Westerner? As a Christian? As Gwen? — assisting them. We can judge the lack of helping as ‘oh, how coldhearted, that poor person.’ But Japanese are doing it from a cultural kindness, a mutual understanding — don’t point out that person’s foible. It’s the same reality but you’re seeing it completely differently. That’s constantly what I feel we’re doing here in Japan, in our communities, and with one another.

Do you see that as a broader problem? Inevitably, Japan is becoming more of a mixed country. But do you think Japan can truly become a multicultural country?

If it had the will. I’m not sure it has the will to or feels the need to become a multicultural country. They don’t necessarily need the refugees. But they do need migrant workers, whether they know it or not.

The reason I asked you about still feeling like “Who am I to critique Japan?” is that I recently had an argument with my husband about this. I feel like I’m living here, we’re married and this is my home, so therefore I have a right, even a responsibility, to critique the Japanese political situation, just as I would in the United States. The other day he said something along the lines of “You should look at what America is doing” and I got really upset. For me, it was a question of, “How long do I have to live here before I’m allowed to say something about Japanese society or politics?”

You absolutely have the right. But you have to be sensitive to your audience. One of my first missionary duties was to bring the truth and the goodness and the beauty of God, and then I realized no, we all have our own truths.

So you’ve changed your feelings about that missionary attitude, about trying to bring God to more Japanese people?

Yeah, it’s interesting, I must admit that, although I came here as this nesshin missionary, my attitude changed rather quickly. I think as I studied more Japanese culture and history and experienced it, I changed. Also, after Vatican Two, there was a push to be more respectful of other religions. We reached out to Buddhists and became much more collaborative. I made sesshin and practiced zazen. I felt there was so much more to receive from Japan. To give, but also to receive and to try to understand and appreciate.

I realized how much more I needed to know my own faith, and to become more a woman of prayer. Then, it was more being and living than doing. It doesn’t matter what you do. It’s the person you become. Just be loving, caring and forgiving, and other things will come from that.

Winifred Bird is a freelance journalist and translator focusing on the environment and architecture. From 2005 to 2014 she lived in rural Japan, where she wrote about biodiversity, agriculture, and the impacts of the nuclear disaster for publications including the Japan Times, Christian Science Monitor, and Yale Environment 360. She currently lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.