Impossible to Imagine: A film by Felicity Tillack – Reviwed by Mandy Bartok

Impossible to Imagine: A film by Felicity Tillack. Bayview Films. 2019

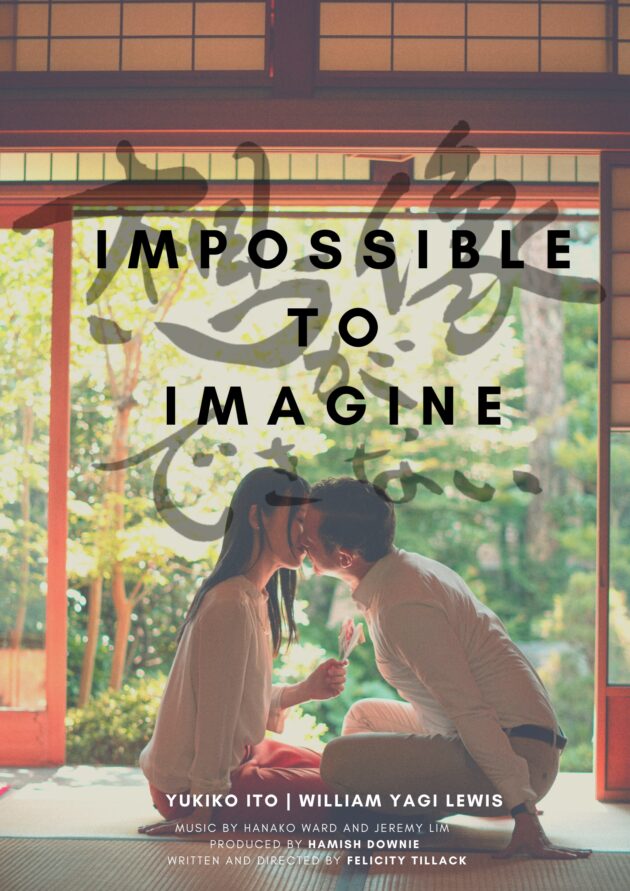

Impossible to Imagine, the title of Kyoto-based Australian filmmaker Felicity Tillack’s debut effort, doesn’t give the viewer much to go on. The film’s poster, with its serene tea house garden backdrop, suggests a romance and plenty of Japanese aesthetic beauty. While love does indeed anchor this thoughtful, character-driven film set in Kyoto, the movie’s overarching aim seems to be to explore larger questions of societal change.

As the film opens, we meet Ami, the young owner of a traditional kimono shop in a part of Kyoto that doesn’t see many travelers. Her desire to cash in on a slice of the recent tourism boom as a means of saving her family’s failing enterprise eventually leads her to biracial business consultant, Hayato. Born of Japanese and Australian parents, Hayato’s upbringing in two different societies clearly informs his world view. While his forthright manner brings success to Ami’s business, it’s a significant hurdle in the burgeoning relationship that develops between the two leads. Hayato sees only the chance to blaze one’s own trail, both individually and for the two of them as a couple. Ami feels constrained by her filial responsibilities, particularly the care of her widowed father, and generations-old adherence to “but this is the way things have always been done.”

The Kyoto we meet in Impossible to Imagine is not the city displayed in glossy tourism brochures. Absent are the gratuitous shots of Ninenzaka or of the ancient capital’s many UNESCO World Heritage Sites. One montage of notable spots in Higashiyama stands out more for its focus on the neighborhood’s over-tourism than its architectural beauty. Instead, Tillack chooses to focus on the small details—a neighborhood shrine next to a cement apartment block, for example—and the workaday districts that most Kyotoites call home. Through this lens, we see the city as it, perhaps, sees itself: an ancient capital with 21st century residents, struggling to walk the shifting line of devotion to tradition and a desire to break free from the past.

Tillack eschews the tendency of many first-time film directors to wrap up the romantic plot in a neat package with a bow. Spoilers aside, the relationship arc may leave some surprised. If Tillack’s purpose, however, is to call attention to Japan’s societal shifts, that goal has been more than met. As we barrel headlong into a spiraling population crisis, how will Japan redefine itself? What role will biracial and foreign residents play in that process? What constitutes “being Japanese” and who gets a say in a national identity? The answers—if there are any—will surely differ based on the viewer. There is no one main takeaway from this film, except that this is a conversation we need to have, and perhaps not soon, but now.

Photos courtesy of Felicity Tillack