KJ had a rare opportunity to watch a ‘shita-mōshiawase’ of the Noh play Ataka—a rehearsal occasionally held about one month before the official performance, in addition to the usual dress rehearsal (mōshiawase), when a particularly intense Noh is performed. A synopsis (and download of the play’s script in English translation) can be found here (courtesy of the-noh.com)

MIKATA MADOKA is a shitekata—the actor who specializes in the shite or main role—in the Kanze School of Noh. Born as the second child of Master Mikata Ken and brother and shitekata of Mikata Shizuka in Kyoto, 1969, he first appeared on stage at age four. He apprenticed to the 13th Hayashi Kiemon in addition to his father, has performed for TV and movies and in many countries including the USA, China, Spain, Canada, France, Switzerland and England. Also, he performs in venues such as the temple reception rooms, hotel bars and dinner shows as well as traditional Nohgakudo theaters. A founding member of ‘Nohgaku Kagamiza’ in Nagoya, he serves as head of Mikata Madoka Seishokai and teaches in Kyoto, Gifu, Nagoya and Tokyo.

Toyoshima Mizuho interviewed Mikata Madoka prior to the official performance, to learn about the unique spirituality of master and vassal as depicted in Ataka.

Toyoshima Mizuho: It is a little less than one month before the official performance day. I am quite amazed to see the rehearsal at such a very high level at this time. The one and half hours felt like a real performance, just without the costumes and masks. What is your opinion?

Mikata Madoka: I can give it only a 30% evaluation, compared with the final performance that I have in mind.

Really? I didn’t notice any mistakes! … I have heard that this play Ataka has the largest number of actors (1) among Noh performances played today. The speed and rhythm among all the actors seemed perfectly matched. How is that possible?

We had a brief meeting before today’s shita-mōshiawase and performed straight away. In Kabuki, performers practice continually together to prepare for a performance, which is different from the procedure in Noh.

Today’s performers are all direct students of the 13th Hayashi (2) Kiemon sensei and, so to say, we are peers who shared the food out of the same pan. And we acquired a particular coloring of performance style. It is also exciting to perform together with actors who have different backgrounds, but there is a risk of inconsistency, especially for a ‘heavy’ performance played for the first time by a shite like myself this time. Peers have similar chemistry and are mutually compatible as we followed the same path of practice as apprentices. My elder brother and my direct senior are appearing too. Further, this play Ataka has been performed repeatedly, so each of us has experience of being part of the performance, more or less. In addition, our master trained us strictly to a high level throughout our apprenticeships. A Noh performance is a composite art resulting from these various factors.

How is it directed?

The shitekata also plays the roles of promoter, producer, and director, since the Noh world is influenced by the traditional za/座 (3) system. Therefore, all the players including the hayashikata (instrumental performers) and wakikata (the Noh actor who specializes in the waki [supporting] role) ask for my direction as to how I want to perform. Based on that, today, we had a spirited critical discussion right after the shita-mōshiawase. Each of us will practice on our own after today and we’ll have one last mōshiawase just before the official performance.

At the Ataka barrier gate, Benkei hits his lord Yoshitsune in front of a barrier keeper appointed by the feudal lord Minamoto no Yoritomo (4) (Yoshitsune’s brother). If Yoshitsune were Benkei’s lord, it would be impossible for Benkei to hit him like this. Therefore, hiding his unbearable emotion, Benkei dared to hit his lord Yoshitsune to prove that he was not his lord and thus that they were not the wanted party. In fact, the barrier keeper realized that they were deceiving him, however, since the scene was so heart-rending, it is said that the keeper pretended not to realize it, so he let them go through the barrier. Here, the reason that a child player takes the role of Yoshitsune is due to an aspect of Noh that symbolizes a characteristic of a role. In this case, the role of Yoshitsune is that of a person who needs to be protected, and essentially speaking, a child is such a person. Thus, when a child player performs Yoshitsune, it is made clear who needs to be protected on the stage. By the way, a child player is not forced to perform the role. His participation can be cancelled at any time if he shows reluctance.

Why is “Ataka” particularly recommended to non-Japanese audiences?

I think that Ataka reveals an aspect of unique Japanese spirituality. Further, while it is a challenging performance for actors that requires subtle skills instructed orally by a master, the story structure involves a powerful psychodrama, and I think the roles and the presentation evoke the audience’s emotions directly by the senses without depending completely on the words. For instance, there is a scene in which I (as the shite, Benkei) beat Yoshitsune (played by a child, my son). If you see a photo of the practice scene (see photo), I may appear to be abusing my son, however, when you see the play in its entirety you can see that’s absolutely not the case.

It is a story of the lord and vassal relationship between Yoshitsune and Benkei, whose lives are risked. Whenever Benkei comes in front of Yoshitsune, he always keeps his eyes down and never looks directly in his lord’s eyes and addresses him with his hands on the ground, kneeling. This is the supreme expression of his loyalty to his lord Yoshitsune. There is a scene in which this powerful giant Benkei weeps in spite of himself: his lord Yoshitsune is now a fugitive, being chased in fear for his life though he has committed no crime (basically because of the relationship with his brother Yoritomo). As his vassal, Benkei feels it is his absolute duty to help his lord at any cost, even if it could be at the cost of his own life.

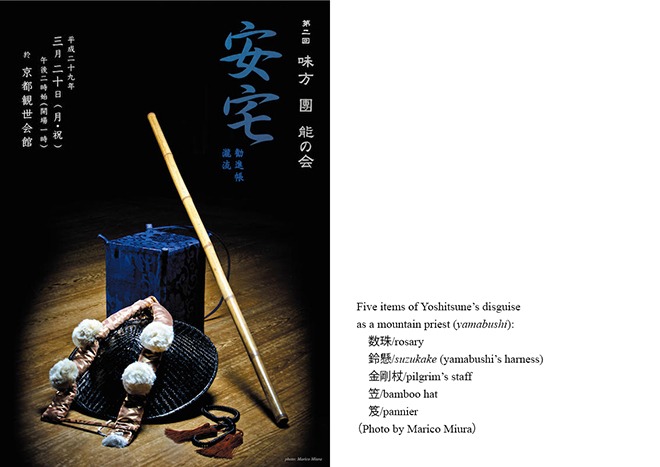

To deceive the barrier keeper of Ataka, Benkei takes a pilgrim’s staff that Yoshitsune carries and beats him with it to prove that he is not the lord Yoshitsune and is merely a lower-class mountain porter who is just carrying a pilgrim’s staff for the group, who are disguised as mountain priests. The very moment when he (I as shite) takes the pilgrim’s staff out of Yoshitsune’s hand, he shows a deep reluctance, feeling enormous pain due to what he is about to do to his lord. That is a terrible predicament for him, knowing that otherwise, everyone will be killed. I’ll perform the moment of Benkei’s reluctance, which can be said perhaps to be an expression of his love as a man.

What do you mean by “the lord and vassal relationship” in this story?

Benkei who was giant, well-known for his enormous strength, was never defeated until he encountered Yoshitsune, who was the 1000th person whom Benkei tried to cut down by sword on the Gojō-Ōhashi Bridge in Kyoto when young Yoshitsune was crossing. After that Benkei pledged his loyalty to Yoshitsune as his lord. It may sound just simple when we hear “the lord and vassal relationship,” however, it is something that never changes, once pledged, no matter what may happen through life. The lord, too, is endowed with power and virtue that meet such a pledge. And, especially Benkei’s chivalry was so strong that he could sacrifice even his own life to protect his lord.

We can sense the compassion of Yoshitsune towards Benkei when he weeps over his predicament, falling to his knees after passing through the Ataka barrier: Yoshitsune consoles Benkei, saying that heaven’s protection must have been with them for Benkei to make such a quick-witted response in that absolutely desperate situation. In response, Benkei cries inconsolably, being touched by his lord’s generosity [because for him, what he had just done was so unbearable]. Their connection can be perhaps described as deeper than a blood relation, I think. On the stage, audience can probably feel their empathy directly, not by words, I believe.

I see. Do you think such spirituality flows deeply in the Japanese traditional lineage of culture even today?

Yes, I think so.

The relationship between master and apprentice in the Japanese traditional cultural framework, like Noh or tea ceremony, is also absolute. Do you find anything in common with the relationship of lord and vassal?

Yes, I do. When I am given practice by my master, I never take my eyes off my master. Instead, I sit down on my knees with my hands in front of them on the floor and entirely concentrate on listening to him. We are not allowed to take notes. Someone studying tea ceremony told me the same thing, for instance. I mustn’t fail to understand any single word from him, as his words are uttered especially for me. I must just fully concentrate on my master. I occasionally see, for instance, an overseas trainee stretching out on the floor and taking notes of what the master says. The same can be seen among young Japanese. Taking notes may seem reasonable, asking the master, “Please wait, as I’m writing” and so on. But this attitude will lead to missing something: their master’s gaze, expression or even his breath and pause between lines. The whole nuance around his words is just too precious to miss out on. I personally think that it actually is most improper to think you can simply write down notes. We Noh actors are trained not to take notes and are not allowed to forget anything once it has been taught. There is no second chance. Therefore, we devote ourselves completely while in practice as if it costs our life.

I don’t mean to say that everyone should be like that. I know only my work and I just feel from the place where I stand, a kind of universality in any relationship when we have complete surrender. It is not slavery but is maybe an ultimate form of compassion or even love. I think that the audience could feel it each in their own way and find some empathy from Ataka. No words are needed to feel empathy, right?

Now I see what you mean when you said before this interview, “the space on the stage in front of the kagami ita (5) never looks the same when a performance is over…”

I hope this extreme form of their empathy can evoke a heart-moving connection with the purity in today’s audience minds, either Japanese or non-Japanse who are very busy to come and sit to watch. (Laughter)

I always feel Noh offers us an opportunity to connect with the empathy that we all have, but which we are often too busy to feel… I understand “Ataka” has a particularly dramatic power for that. Thank you for this precious opportunity!

FOOTNOTES

1 In this play, Benkei (the shite) and nine actors protecting Yoshitsune (played by a child actor) appear together on stage in addition to a waki actor, four musicians and eight chorus players, making it very powerful and dramatic effect.

2 Hayashike (Hayashi family) is one of the ‘Kyō Kanze Five Houses’ that taught the Su-utai style (vocal-only Noh performance with no dancing or instruments) after the head of the Kanze School moved to Edo (today’s Tokyo) to serve the Tokugawa Shogunate. Hayashike is the only family that has continued to date (though Su-utai is also taught by other shitekata today).

3 The za/座 were one of the primary types of trade and entertainers’ guilds in feudal Japan. The za/座 as an entertainment group is based on a main tayu/大夫 or head master of a school (iemoto/家元) and is comprised of entertainers. It was called by a name like the “~~za“. This basic structure is still functioning to maintain the quality and level of the art and to enhance its development.

4 Minamoto no Yoritomo, 1147-1199. The founder and the first shōgun of the Kamakura Shōgunate (around 1185-1333) of Japan.

5 kagami ita (鏡板) The wall at the back of the Noh stage with a full-sized old pine tree painted in color on it. Gods are thought to descend and their presence resides in the pine tree, and thus the tree is a subject of worship and the space holds the sacred.

This is an online spinoff from a special series of fresh viewpoints on Noh, INVITATION TO NOH, published in the year of Kyoto Journal’s 30th anniversary. Special thanks to the-noh.com

Noh has been one of TOYOSHIMA MIZUHO’s passions since she moved to Kyoto in 2001. She is a book translator and interpreter; has been a long-time KJ contributing editor and a consulting editor since 2011. Inquiries concerning this article will be very welcome: contact@kyotojournal.org

Photos by Marico Miura