“Vision,” the theme of this year’s KYOTOGRAPHIE International Photography Festival, seeks to highlight photography’s power to overcome barriers and satisfy (in the words of New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield) “that terrible desire to establish contact.”

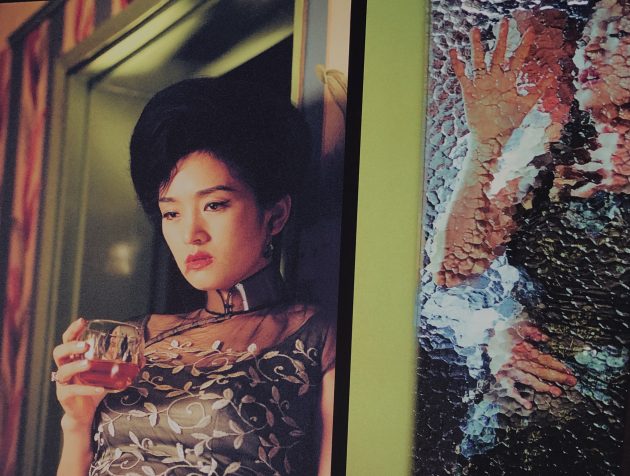

Postponed from its usual April slot due to the pandemic, co-founder Lucille Reyboz sees this year’s festival as a return to its “homemade” roots, which took shape in the aftermath of the 2011 Triple Disaster. Not surprisingly, a larger proportion of the artists participating are from overseas, and the number of exhibitions, after peaking at 16 in 2016’s “Love,” has decreased to just 10 this year. Location-wise, there are a few stalwarts, such as the Kondaya Genbei, where Wing Shya’s dreamy-colored Kodachromes flow down the length of the Chikuin-no-Ma like an unfurled obi, and Ryosuke Toyama’s moving tribute to monozukuri or artisanship at Ryosoku-in Temple, but the majority of the main exhibitions are in spaces that are being used for the first time. Most of these are located within Kyoto’s downtown area, while many former locations are hosting exhibitions for KG+, which has seen a tremendous explosion in variety and vitality this year, with over 60 shows vying for attention.

This year’s festival seeks to highlight photography’s power to overcome barriers and satisfy (in the words of New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield) “that terrible desire to establish contact.”

A good example of how photography can overcome isolation can be seen in the work of young photo/sewing/fashion/performance artist Mari Katayama, on display at the Shimadai Gallery on Oike Street (see KJ#97). Born with a rare condition that deformed both feet and one hand, Katayama’s female relatives spent hours sewing special clothes to cover her bulky orthotic boots. In third grade she was so severely bullied that she chose to have her feet amputated so she could wear prostheses and “normal” clothes. She embellished her prostheses and adopted a punk persona, hoping to find like-minded friends—only to have her peers avoid her all together. She retreated to her room, concentrating on creating and posing with fantastically beaded, embroidered and stuffed objects that caused a sensation in the Japanese art world when she posted photographs of them on MySpace.

In the selections from her “bystander” (2016) and “Shadow Puppet” (2016) series hanging in the gallery’s kura, her persona alternates between scary and seductive, sprouting a profusion of Ursula-like tentacles while also sexing it up in corsets and high heels. International recognition came when curator Simon Baker discovered Katayama’s work at a photo fair in Amsterdam. Finding acceptance overseas, not as a representative of “disability,” but as an artist offering a unique and valuable perspective, coupled with motherhood in 2017, seems to have had a softening, even healing effect on her art, as can be seen from the large photographs from her newest “In the Water” series lining the perimeter of the gallery. No longer bristling with stuffed appendages—after becoming a mother she did not want to have needles and other sharp sewing implements around the house—the newest photos focus on her deformed limbs as aesthetic objects, not so much daring us as inviting us to look.

At the same time, these images make an appeal to the wider world beyond the sanctuary of her room: the exhibition’s title, “Home Again,” refers to her return to her native Gunma, where in the 1880s the water was poisoned by runoff from the Ashio Copper Mine in neighboring Tochigi. An installation in the gallery’s interior connects this, Japan’s first environmental disaster, with places such as Minamata and Flint, Michigan. Katayama’s physical difference is genetic, not the result of environmental pollution, but because these images resonate with images of earlier victims of environmental poisoning there is a connection between a plea for kindness among individuals to a plea for kindness to the matrix of human existence.

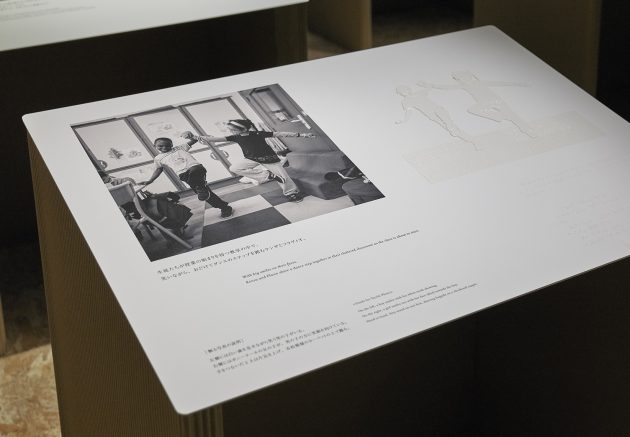

In her belief that “photography has more than visual qualities,” Marie Liesse’s “Story of a Bridge between Two Worlds” at the Atelier Mitsushima Sawa-Tadori just across from the eastern gate of Daitoku-ji Temple, is the exhibition that most closely embodies this year’s festival theme. The project got its start when her husband’s high school friend, Jean-Lin, passed away and the couple discovered there was only one photograph of him, causing them to ask why do we assume that people who cannot see are not interested in being seen and memorialized in a photograph? Known for her photographs of children, she spent 10 years photographing the students at the school where Jean-Lin had gotten his early education, l’Institut Nationale des Jeunes Aveugles, the first school of its kind in the world. Her photographs exhibited here, curated by Marina Amada, document their “very special childhoods” as well as their efforts to be included in mainstream society. For this exhibition Liesse worked with a visually-impaired art teacher and engraver, Florence Bernard, to create embossed photographic prints that the blind students can experience with their sensitive fingertips.

The owner of the studio, artist Takayuki Mitsushima and Kojiro Hirose, of the National Ethnology Museum, both of whom are blind, served as advisors for the exhibition. The former is a pioneer in creating artworks for visually impaired people, while the latter is currently working on establishing a “Universal Museum” that can be enjoyed by everyone. To enter this exhibition visitors must find their way, guided by a rope, through a pitch-black hallway, which is set up like a classroom, with the photographs and tactile photographs arranged side by side on slanting school desktops.

While the photographs of the blind children are beautiful and moving, to a sighted person, the embossing seems underwhelming, which is precisely the point. During the last 2 weeks of the Festival, Kyotographie is arranging to pair visually-impaired and sighted students to take in the exhibition together. To some, the idea of “art for blind people” may seem like a joke; but think of all the instances in which people limit their view because of perceived disabilities; for example, the assumption that people who cannot read kanji are incapable of appreciating Japanese and Chinese calligraphy.

The fact that attendance has far exceeded expectation shows that a shared vision is exactly what we need right now.

Co-founder Yusuke Nakanishi envisions the festival as a form of “media” that is not controlled by the government. As can be seen from the controversy surrounding director Hirokazu Kore-eda’s “Shoplifters,” in Japan where topics such as poverty and disability are subject to strong taboos, holding them up to the light is a political act. Adding “old age” to the list, a third installation that may draw criticism from Japanese audiences is a pair of exhibitions housed in the Itoyu Machiya, a row of five interconnected townhouses located in a roji alley opening off Shinmachi street, (and just up the street from the Terminal Gallery, site of SHITSURAI – Offerings VI, featuring works by John Einarsen, Tomas Svab, Everett Kennedy Brown and other artists). Atsushi Fukushima received last year’s KG+ Award for his photographs taken in the course of his part-time job, delivering ready-made meals to elderly residents in his neighborhood in Kawasaki. His show this year, “Bento Is Ready,” documents the squalid living conditions and deteriorating bodies of his customers, who mainly lived alone, their once or twice-daily meals paid for by relatives.

A trained photographer, he brought his camera along on the job, but it took him six months to work up the courage to ask his customers’ permission to take their pictures, thinking there was no way they would consent to having their deteriorating bodies and squalid living conditions recorded for posterity. He was surprised that they agreed, and the first room of photographs seems filled with a kind of morbid fascination with his subjects’ proximity to death. However, over the course of 10 years, during which he quit the job several times, he began to see something admirable in his customers. Just the act of receiving the food, and nourishing their bodies showed that they considered their lives to be worth living, and the fact that they carried on alone, not wanting to be a burden on others, the sign of a certain nobility. Fukushima’s photographs in the adjoining house reflect this change of perspective, which enabled him to bring the series to a close.

In Japan where topics such as poverty and disability are subject to strong taboos, holding them up to the light is a political act.

Further along down the alley, occupying two more machiya, is Marjan Teeuwen’s architectural installation, “Destroyed House – Kyoto” (2020). In different places around the world, Teeuwen takes condemned houses and guts them, using the rubble to make fantastic constructions, or reconstructions—giving old houses a third act, one last chance to achieve transcendence, which she documents in large-format photographic prints.

For over a thousand years, Kyo-machiya have been elegantly constructed of wood, clay, and plant fibers. According to one survey, at present, they are disappearing at a rate of 800 a year because after WWII their upkeep came to be considered too burdensome, and their humble materials too costly to make proper renovation possible. Often, before being demolished, they will be “renovated” with corrugated metal, cheap tiles, linoleum and plastic, like an elderly whore made to paint her face and turn one last trick before expiring. Passing through Itoya machiya’s dingy streetfront, visitors encounter a large white circular opening, made of piled-up white plaster, intersected by a black cross. Next door, Teeuwen and her assistants dug out the ground beneath the house (machiya do not have cellars) to create a space 8 meters high, construction/life/transcendence and destruction/death/dissolution being the obvious metaphors.

Teeuwen has written that her installations reference war, but in the case of Kyoto, which famously is one of the only Japanese cities to escape widespread bombing during WWII, the damage is self-inflicted. For a longtime Kyoto-dweller like me, looking up at the exposed vaulted roof, with its perfect wooden tiles and beautiful sculpted beams, the overwhelming feeling is mottainai—what a waste. The story of how this was allowed to happen, the story of people moving to the city to work post-WWII and the disappearance of three-generation families, the elders being the ones who were supposed to teach the rising generation about the value and upkeep of their architectural heritage but who ended up living and dying in isolation, is being told at the house up the alley.

Besides providing these glimpses of an unfamiliar Japan, KYOTOGRAPHIE displays a very “French” appreciation of both the antique and the modern. The Meiji-period Kyoto Prefectural Office is the site of Pierre-Elie de Pibrac’s “In Situ,” the photographic traces of his two years embedded in the Paris Opera Ballet, including some shots of the great Nicholas Leriche at the end of his career. In “Heatwave,” in the newly-opened Hosoo Gallery on Aneyakoji Street, Elsa Leydier uses the Rayograph technique (named after its inventor, Man Ray), in which photographic images are made without the use of a camera by placing them directly on photographic paper and then exposing them to light to make a statement about global warming.

Lucille Reyboz spent part of her childhood in Africa, and KG has played a role in introducing the work of Africa-based photographers to Japan. Last autumn KG brought Senegalese photographer Omar Victor Diop to photograph the denizens of the Demachi Masugata shotengai, or shopping arcade (see KJ 89). A video playing in the first-floor café of Delta, KG’s new year-round permanent exhibition space, located in the shotengai, shows him causing a local commotion as he strolls down the arcade, resplendent in a formal traditional hakama.

Here is a glimpse of the secret history of the alliance between people of African descent and the people of Japan, going back to Japan’s defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905.

The results of this project can be seen in his dynamic portrait-collages of twenty of the shotengai’s business owners, who volunteered to be photographed holding the attributes of their trades. The photographs hang on the walls of the café and swing suspended from the ceiling of the arcade. The subjects’ poses are unusually dynamic, with swaths of African textiles serving as a kind of window into an unconscious, half revealed by the kimono shop’s furisode and the greengrocer’s fluorescent price tags.

Here is a glimpse of the secret history of the alliance between people of African descent and the people of Japan, going back to Japan’s defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905. Thrilled by the fact that a “nonwhite” nation had given the lie to the seeming inevitability of white domination, a group of African-Americans traveled to Paris to petition the Japanese delegation, who had been given a seat at the victors’ table at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, to insert a Racial Equality Proposal in the Covenant of the newly-established League of Nations. Its defeat in the face of objections from Great Britain, Australia, and the U.S. is one reason for Japan’s turn away from cooperation with the west and its turn towards militarism and nationalism after World War I.

Selections from Diop’s “Project Diaspora” series hang in the Kyoto Prefectural Office’s elegant Main Building. The photographs are inspired by well-known paintings of distinguished 15th and 16th-century African diplomats, politicians, and scholars, and show that far from being isolated from the rest of the world, Africa had many connections with India, Europe, and the New World even at that distant time. Each figure holds a football-related accoutrement, referring perhaps to the status of modern-day Africans being simultaneously “hero” and Other in modern-day Europe.

Finally, the vicinity of the real bridge spanning the confluence of the Takano and Kamo Rivers is the site of Kyoto street photographer Kai Fusayoshi’s “Kamo River Wandering,” a modern recreation of his open-air photo exhibitions from the 1970s. Kai has been bringing people together through these exhibitions and his nomiya, Hachimonjiya, and before that, the Honyarado coffee house, for nearly fifty years (see cover, KJ#23, “Neighborhoods”).

The photos that line both sides of the river were taken between 1974, two years after Honyarado was established, and 2017, two years after it was burned down. The black-and-white collages are filled with people: macho working men, off-duty salarymen, street musicians, pawnbrokers, monks, anti-nuclear activists, schoolgirls, gaki (urchins) and of course bijin (beautiful women). Local people gather around the displays, perhaps hoping to find a picture of a loved one, or themselves. His pictures make us smile because we can all see ourselves in them. (Kai’s work is also shown in Kyoto Station’s sci-fi Skyway).

We are fortunate that this year’s festival was able to go on, despite these adverse conditions. The fact that attendance has far exceeded expectation shows that a shared vision is exactly what we need right now. KYOTOGRAPHIE 2021 will also take place in September before returning to its regular springtime slot in 2022.

[Special thanks to Everett Kennedy Brown, Regis Arnaud, and Ken Rodgers]

Kyoto Journal and KYOTOGRAPHIE are official partners this year, and we have been enthusiastic supporters ever since the festival first came on our radar (see KJ Digital Issue 81).

Susan is KJ’s Associate Editor and has attended every edition but one of the KYOTOGRAPHIE festival since it began in 2013.