KYOTOGRAPHIE has been successful partly because photographic images have the ability to transcend linguistic differences through ishin denshin: wordless communication, heartstrings vibrating in harmony.“Vibe,” which situates ishin denshin within a specific locale, is a fitting theme for the photography festival, now in its seventh year.

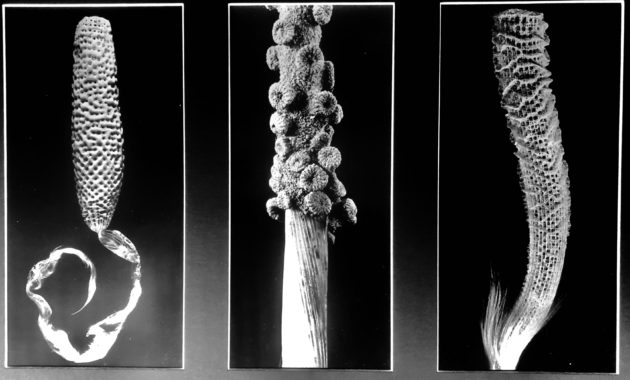

Of the eleven main venues, “The Forms of Nature: 100 Years of Bauhaus” illustrates this theme the most faithfully. Alfred Ehrhardt’s large-format and vintage print black-and -white photographs of shells, corals, and North Sea tidal flats look uncannily like protozoa, skin, and hair seen through a microscope, and, as curator Sonia Voss points out, are reflected by the green “macrocosm” of Ryosokuin Temple’s extensive gardens outside the window.

However, despite the difficulties of transcription and translation, words cannot be dispensed with entirely. This is especially clear in the case of “Wild,” the major venue in the Museum of Kyoto Annex. Master portraitist Albert Watson’s reputation perhaps speaks for itself. A photographer’s photographer, he is famous for his “artisanal” handling of the raw materials of photography: to achieve his astounding portrait of Mick Jagger, Watson rewound his film and shot Jagger’s face over that of a leopard repeatedly until he achieved a perfect double exposure. This I learned from reading the caption beside the photograph in the exhibition. Unfortunately, neither technical information nor backstories were provided for his other famous works, such as his images of Ryuichi Sakamoto and The Isle of Skye, nor for any of the other photographs, either as labels on the wall or in the pared-down catalogue. Similarly, in the brief address he gave during the press tour, the photographer seemed more interested in talking about BMW, the exhibition’s main sponsor, than about his craft. I know that it’s not fair to compare but remembering last year’s Jean-Paul Goude extravaganza in the same space last year, the effect was puzzling.

This year’s crowd-pleaser, “What a Wonderful World” by young Polish photographer (b. 1984) Weronika Gesicka, photomontages U.S. stock photographs to reveal the fictitious nature of the so-called era of American greatness, reflecting a wry sense of humor similar to that of such contemporary Polish cartoonists as Pawel Kuczynski. The scenography is some of the most elaborate in this year’s show: photos are displayed in a tiled hallway and a 1950s living room, complete with a sofa, rabbit-eared TV set, bouffant-hairdo mops, and a backyard’s worth of treacherous playground equipment. Such works as Roland Marchand’s Advertising the American Dream (1985) and the films of David Lynch and Michael Moore (who used the title song as background music for a sequence about CIA-orchestrated atrocities in Bowling for Columbine) have covered this territory before, to the extent that, as John Einarsen remarked, to most Americans, the un-montaged photographs themselves would have been enough to get the message across.

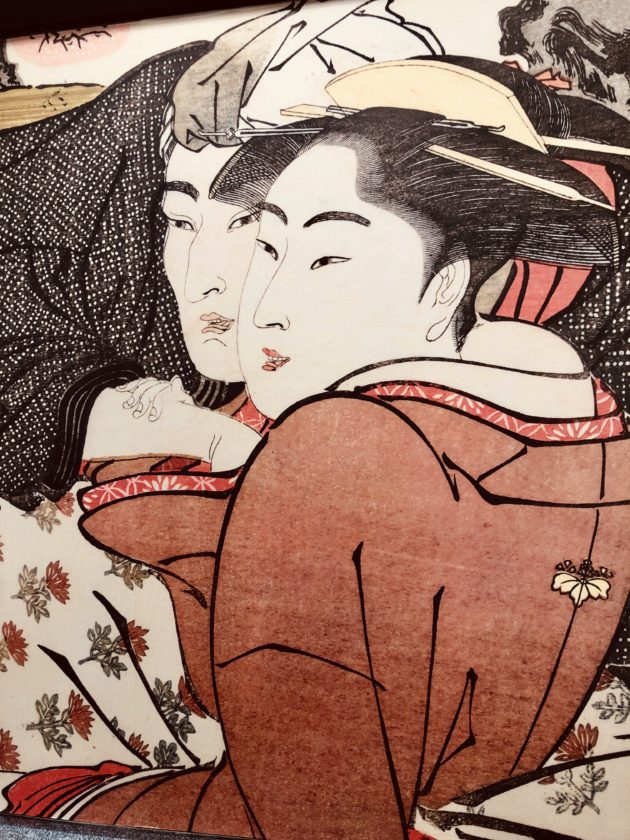

Another popular (and also very funny) show is “Pierre Sernet & Shunga” at The Kondaya Genbei Chikuin-no-Ma on Muromachi Street, which drew large crowds when it originally opened at the Chanel Nexus Hall in Tokyo. The shunga, literally “Spring pictures,” seen here are from a collection of Edo Period erotic prints that were among those displayed at the British Museum in 2013-14, and later, with much hesitation, at the Eisei Bunko Museum in Tokyo and the Hosomi Museum in Kyoto. This reluctance to mount a public exhibition in the country of the art form’s birth was seen as surprising considering the fact that shunga are widely available as books. Richard Collasse, chairman of Chanel G.K., blames this “hypocrisy” on the influence of nineteenth century “American puritanism,” but there is in fact a long history of producers and purveyors of shunga being censored, jailed and even tortured by the Tokugawa authorities, starting with the Kyoho reforms in 1722 (the catalogue for the British Museum exhibition devotes an entire chapter on this subject), because, as Ian Buruma has argued, Japanese culture often views expressions of overt sexuality as politically transgressive. In this context it is interesting to observe that when the show first opened in Tokyo, the organizers considered having a “ladies’ day” to encourage supposedly prim Japanese women to attend. The need for such accommodations was soon dismissed, and in fact female attendees outnumbered men, suggesting that Japanese women find the public representation of “private” body parts to be intensely liberating, as can also be seen in the works of women artists ranging from Yoko Ono to Megumi Igarashi.

The British Museum catalogue is careful to point out that “early modern Japan was certainly not a sex-paradise; there was a huge and exploitative sex industry,” and while a few of the prints depict rape and one especially creepy encounter between a gray-skinned, claw-fingered Dutch sea captain and a stoic sex worker, the mood of the show is predominantly light (shunga were also called warai-e, literally “pictures to make you laugh”). Among the courtesans and clients, housemaids and traveling salesmen, and samurai and geisha, we are introduced to such characters as the mabu (married woman’s lover, or a sex worker’s non-paying client – “a backdoor man”), and the otoko mekake (a widow’s kept man). In the seemingly-endless array of couplings (and the occasional threesome) most of this would escape us unless we read the dialogues that occupy the top part of most of the prints, which are excellently captioned in both English and Japanese. Shunga, after all, were the first manga. If civilization has made any progress at all, it can be seen by the fact that the multi-oriented, multicultural erotic couplings seen in Pierre Sernet’s silhouette portraits can be assumed to be entirely consensual.

The trio of shows, “About Her, About Me, About Them: Cuba through the Art and Life of Three Photographers” at y gion also suggests that by introducing the possibility of transgression, political repression can be seen to promote artistic expression. This thought occurred to me as I viewed how the most senior of them, Alberto Korda, a fashion photographer before the Revolution, seemingly had no trouble re-adjusting his aesthetic vision to find beauty in the female faces of the revolution, and to create his iconic portrait of Che Guevara. Rene Pena, who was a baby when the revolution took place, treated his own body as a “stage” upon which to enact the history of the times trough which he lived. Alejandro Gonzalez, the youngest of the three, uses photography to critique the gap between the revolution’s promises and the reality, through his diorama re-constructions of historical events and his photographs of street children and members of Havana’s LGBT community, who are absent from the official historical narrative.

Of course, the most trenchant social criticism comes from within one’s own society. For 12 years, Kosuke Okahara was involved in the lives of six (five are featured in the show) young Tokyo-area women who were addicted to the practice of self-mutilation. The causes: bullying, domestic violence, sexual abuse, and rape are part of the back story that we only learn about in Okahara’s eloquently-written introduction. Their predicament, he writes, serves to “expose a dark underside to contemporary Japanese society.” The photographs, which reveal loneliness and economic deprivation, are intimate, but not voyeuristic. We see the women at home, taking pills (anti-depressants?), preparing to cut themselves, being taken to the hospital in an ambulance. It is wrenching to see that even happy events, such as the birth of baby, are not enough to prevent relapse. The five groupings of photographs are arranged very effectively by Shunsuke Kimura within a larger, pitch-black space, whose oubliettes and wrong turns force us to share the women’s sense of entrapment. The subject of Okahara’s other exhibition, whose he shares with veteran Magnum photographer Paolo Pellegrin, is Kyoto University’s famous old Yoshida Dormitory, suggesting a fascination with the abject, except that unlike the young women who despair of ever finding an “Ibasyo,” a place where they feel good, these upwardly-mobile young men (mostly) can be said to be experiencing “squalor tourism.”

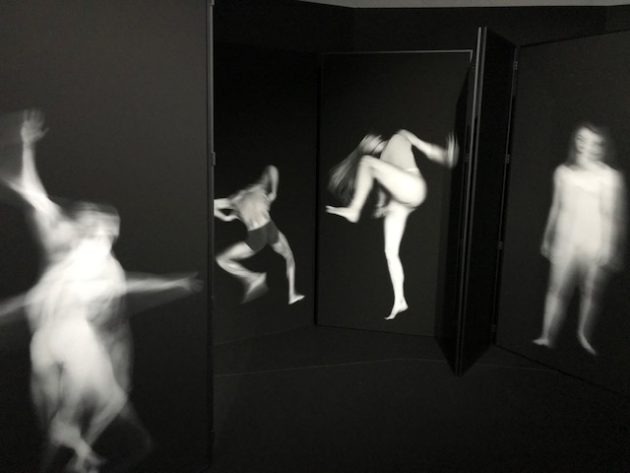

The two other exhibitions that make exceptional use of their venue’s space are Ismail Bahri’s “Kusunoki” and Benjamin Millepied’s “Freedom in the Dark.” Bahri transforms Nijo Castle’s Okiyodokoro kitchen (the only venue being used for the first time) into a giant camera lucida, inviting the viewer to experience a series of site-specific installations, including a glimpse of the camphor tree outside. Millepied’s exhibition, my favorite, is staged within the confines of the brooding black Kurogura Gallery. A photographer, choreographer, and filmmaker, as well as formerly being a principal dancer with the New York City Ballet, and Director of the Paris Opera Ballet, Millepied currently devotes himself fulltime to the Los Angeles-based L.A. Dance Project, which he founded. The entrance hallway is lined with a accumulation of “inexpressive” silhouettes of people crossing Hollywood Boulevard. The darkened circular inner sanctum is lined with a series of highly-expressive life-size monochrome images of dancers in motion alternating with reflective surfaces accompanied by a soundscape composed of the “sounds of L.A., from Bernard Herman to Schoenberg to Stravinsky.” On the second floor is Millepied’s short film, “Reflections,” and further up, a third room at the top of a tower reached by a circular staircase is lined with more black and white photos of dancers’ limbs, smaller in scale. The circular room, with its soundscape of rehearsing dancers’ unglamorous grunts and thuds playing in a continuous loop, invites the viewer to re-examine what Millepied in his artist’s talk called a “corrupt relationship with time.”

KYOTOGRAPHIE has already transformed the Kyoto cultural landscape, and as it solidifies its borders and answers to the prejudices and preoccupations of its corporate sponsors, the energy represented by the 72 KG+ satellite exhibitions scattered throughout the city is more important than ever. The shows by Osamu James Nakagawa at Gallery Sugata and Nao Naido at GalleryMain are especially recommended.

Susan is KJ’s Associate Editor and has attended every edition but one of the KYOTOGRAPHIE festival since it began in 2013.

All photos by Susan Pavloska and Lucinda Cowing