A report by Susan Pavloska

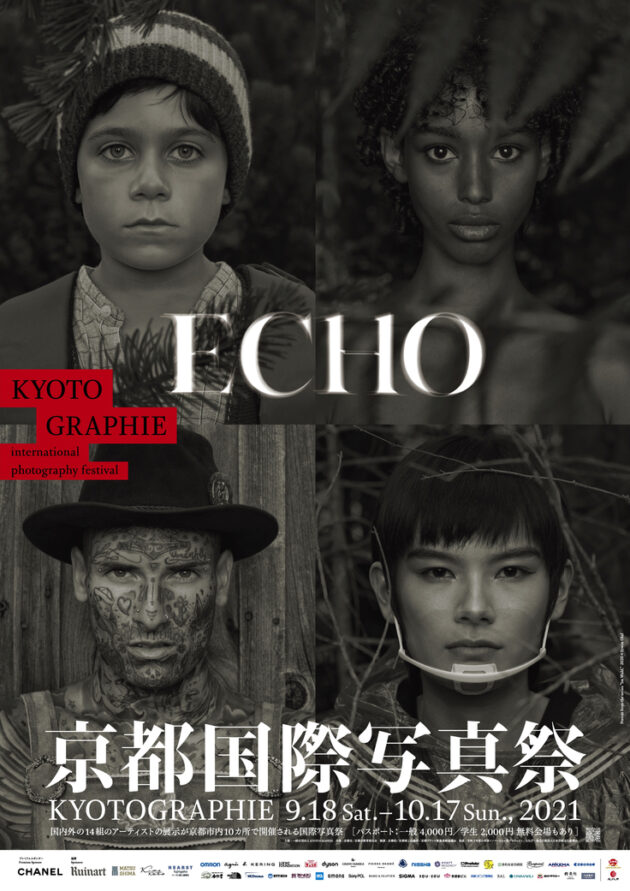

Japan’s first truly international art festival was born of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident, while this year’s edition, entitled “Echo,” has gone ahead amid the challenges posed by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Co-founders Lucille Reyboz and Yusuke Nakanishi recognize that for artists and audiences, the best response to such challenges is not to succumb to numbness or forgetting, but to give trauma a place to echo and reverberate and be fully experienced in order for healing and recovery to occur. Exploring such themes as natural disasters, the pandemic, and sexual abuse, “Echo” might seem unremittingly dark, but among the 14 main exhibitions a current of profound and non-facile hope pulsates to the surface in unexpected ways.

The opening of the centerpiece of this year’s festival, a set of five exhibitions at Nijo Castle entitled “ECHO of 2011,” was delayed for six days due to an example of what Kyoto University Professor Thomas Daniell has called a tendency towards “ritualized pretentiousness” on the part of the guardians of Kyoto’s cultural patrimony. “The Wave: In Memoriam,” by Richard Collasse, novelist, amateur photographie, and retired president of Chanel KK, in the castle’s Tonan Sumi Yagura watchtower, serves as a preamble, admonishing audiences to remember that although the “egoism of the world” shifted the focus to the nuclear accident, the tsunami constituted a far greater human tragedy whose effects continue today.

The main exhibition space in the cavernous Ninomaru Palace Daidokoro Kitchen is strewn with the vivid photographs by avant-garde ikebana master Katagiri Atsunobu of the arrangements he created from wildflowers and weeds at the disaster site, which, “bursting with vitality,” continued to sprout, even from the “flexible container bags” used to dispose of contaminated topsoil. The beauty of the flowers and the scenography makes it easy to miss the pathos of the standing photographs depicting arrangements made using the wooden pillars from a barn, gnawed into irregular shapes by starving cattle.

The preceding exhibitions prepare the viewer for the almost unbearable intensity of “Brise-lames” (“Wavebreak”) a performance piece by Damien Jalet and J.R. whose planned debut last year was cancelled because of COVID and instead was realized in the form of a masterfully-filmed performance in the empty Opera Garnier. Under the direction of choreographers Aimilios Arapoglous and Damien Jalet, with live music by Koki Nakano, and set and costumes in shades of white and blue-gray by JR, the lithe bodies of the nine Paris Opera dancers transform from unassuming raindrops, to gentle waves, to a roiling sea, to human beings helpless in the face of an overwhelming force. Their further transformation is difficult to watch – but at the end the dancers, the living and the dead, reach out for each other and coalesce into the final image of a life raft, suggesting, as Albert Camus famously asserted in La Peste, that the forces of destruction in the universe are impersonal and can only be counteracted with fraternité humaine, solidarity.

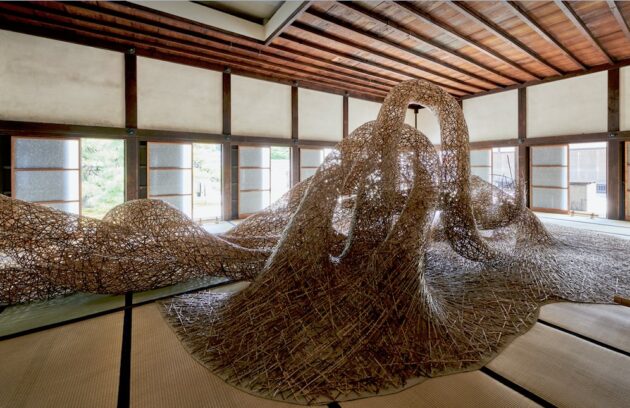

The last two exhibitions in the suite, “Fill in the Blanks” by photographer Kazuma Obara and “STAND,” by bamboo artist Chikuunsai IV Tanabe, underscore the commonalities in the process of recovery from the two disasters and pay tribute to this quality of human resilience, acknowledging that humanity too, is a force of nature. According to the organizers, this group of exhibitions received record levels of attention from the Japanese press, and indeed, they constitute a dignified and appropriate memorial to the victims of this unprecedented disaster.

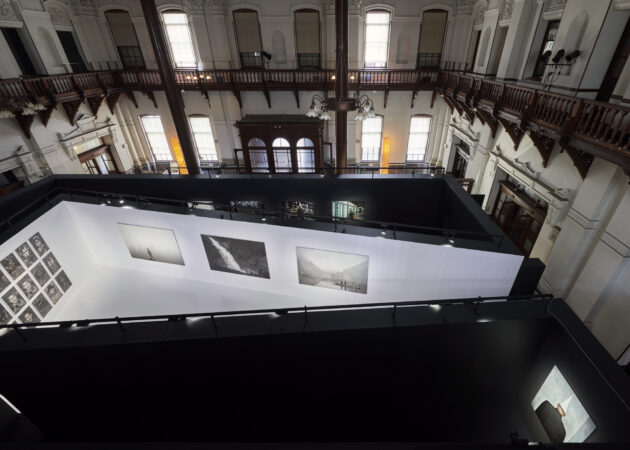

The pandemic is the main theme of Erwin Olaf’s “Annus Mirabilis,” the major exhibition at the Museum of Kyoto Annex on Sanjo Street, which is usually the scene of the festival’s virtuoso exhibitions, including “Mars, a photographic exploration” in 2014 and especially Jean-Paul Goude’s “So Far So Goude” in 2019. The elegant simplicity of Olaf’s high-production, staged photographs suits both the ornate Meiji-period building and the times. The first series, “April Fool,” wrapped in an all-black space, traces a day in the life of a tall, well-built, white man wearing a dunce’s cap as he cruises the empty shelves of a discount supermarket, deserted except for one handsome dark-skinned Essential Worker. Later, he paces the floor of his dining room with the voice of ex-President Trump issuing from the radio on the table. In contrast, the series “Im Wald,” displayed in an interlocked white space, shows people of various ages, genders, abilities, and ethnicities breathing freely out in the wide-open spaces of Bavaria.

The festival’s serious content is leavened by a number of factors, one of which is that the French refusal to see “a conflict between sensuality and intellectuality” (in the words of Richard Collasse) has always been in evidence here. This year both exhibition spaces at longtime Muromachi Street venue, Kondaya Genbei, the Chikuin-no-Ma and Kurogura, are devoted to an exhibition about the life of “lioness” Coco Chanel, the fictionalized subject of a newly-commissioned manga, Miroirs, by Kaiu Shirai and Posuka Demizu. A similar vision can be seen at the sublimely-renovated Hosoo Gallery’s “Women Artists from the MEP [Maison Européenne de la photographie,” supported by the ultra-luxe brand, Kering (“provocateur” David Shrigley’s exhibition, sponsored by Ruinart champagne at ASPHODEL in Gion, is another example).

Seemingly miles away but in the same downtown area is “Manifold” by Sierra Leonean artist Ngadi Smart’s in the third-floor space above the Flying Tiger store on Kawaramachi Street. The venue’s unique design, as initially conceived by Lucille Reyboz, is constructed of 35 mm x 50 cm pieces of wood, evokes the image of both a womb and a primitive dwelling. The design company, miso (headed by Hiromitsu Konishi, with Erika Yamao), reportedly tested various prototypes before they got just the right combination of prickliness and comfort. The exhibition consists of four series arranged in concentric circles around an inner void. As the viewer follows its contours, they are led into an exploration of the newly-fraught term: “woman” from an African perspective.

In the first series, “The Faces of Abissa,” Smart interacts with the participants of a joyful fortnight-long festival of the N’zuma people of Bassam, Cote D’Ivoire, exploring the idea of gender being something that can be put on and taken off as easily as the costumes on topsy-turvy day. In the next series, her portraits of the fabulous members of the taboo drag community in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire in “The Queens of Babi,” points to the nearly-universal fascination with the multiplicity of genders that reside within all human beings. The next 2 series are more personal: “Metamorphosis” uses collage to explore the artist’s feelings about her sacrifice of the physical accoutrements of femininity, including her fertility, to breast cancer treatment, while the last, entitled “Me, First,” explores how women’s secondary status affects even the most intimate aspects of their existence, with the added difficulty of expressing these ideas due to long-existing racist tropes of Black women’s hypersexuality.

As with last year, when Omar Victor Diop was invited to create artworks based on his interactions with the denizens of the Masugata Shopping Arcade, banners of Smart’s photo-collages, “ee don tehm foh eat (it’s time to eat)” adorn the rafters of the site of KYOTOGRAPHIE’s permanent space in Demachi, which boasts a café run by a former chef at the Ace Hotel, Kyoto.

Further demonstrating that it is not afraid to “go there,” the winner of the 2020 KG+ Select competition, Chinese journalist Yingfei Liang, in “Beneath the Scars,” takes on the subject of sexual abuse. Liang’s photographs depict how desire, invested with the importance of a force of nature by the more powerful at the expense of the less powerful, can leave scars that last a lifetime. Recently in France, memoirs such as Camille Kouchner’s la familia grande and Vanessa Springora’s Consent have begun to open up a discussion about a topic that has for too long been suppressed by a reflexively scornful stance towards “puritanical” “Anglo Saxon” sexual mores. Behind each of Liang’s photographs, depictions of scenes of entrapment and defilement that provide a visual representation of an actual incident, is a recording of a voice telling what happened. The stories are read by male and female narrators, underlining the fact that both boys and girls are the victims of sexual abuse. Erika Yamao’s installation, which places translucent-glass dividers between the artworks, brilliantly evokes the compartmentalized vision of sexual abuse survivors.

Not merely breaking taboos for effect, KYOTOGRAPHIE has shown that it is willing to take this topic very seriously, translating and adapting a bilingual Japanese/English edition a pamphlet written by French author Dominique de Saint Mars. The Kid’s Safety Guide (downloadable from the KG website) contains a quiz that parents and children can take together to initiate discussion in a matter-of-fact, non-threatening way in order to protect for children from being caught off guard should this (sadly, very common) situation arise.

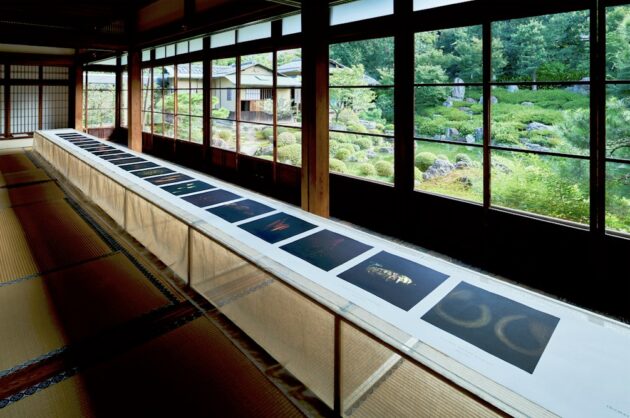

After pondering these realities, two exhibitions on the east side of Kyoto offer reassurance, if not a ray of hope. In the Ryosoku-in sub-temple of Kennin-ji Temple in Gion, a long scroll on which Thomas Dhellemmes’s Polaroid photographs of the ancient and forgotten vegetables from the Potager du Roi at le Chateau de Versailles are mounted spools across the tatami floor, while a few actual specimens, misshapen and dried out, occupy pride of place in the tokonoma. The heirloom vegetables featured in Légumineux (2009) have been quietly seeding and re-seeding themselves since the time of Louis XIV. Their ungainly unbeautiful shapes are a far cry from the perfect agricultural cooperative-approved specimens seen in food stores today, grown from sterile one-generation hybrid F1 seeds developed by multi-national corporations.

Ryosoku-in is also the site of the work of Kyoto-based Yuna Yagi (see “Photography and Ma,” Kyoto Journal 98 (2020)). “The Record of Seeds” records Masatoshi Iwasaki’s efforts to collect and preserve the “DNA memory” of the native species of vegetables growing on the slopes of Mt. Unzen in Kyushu. Unlike the plants grown from F1 seeds, the flowers of Iwasaki-san’s vegetables are full of seeds waiting to be gathered and used to produce next year’s crop. The other part of Yagi’s exhibition captures aspects of the natural environment of Unzen using the cyanotype photographic process in which the object to be photographed is laid directly on photosensitized paper. The bright cyan-blue prints, such as “The figure of a Yokokawa Tsubame Radish after nutrients were transferred to the seeds” (2021) evoke the power of the sun.

The first time Ryosoku-in had served as a festival venue was for RongRong & inri’s previous KYOTOGRAPHIE show, Tsumari Story (2015). This year the pair, co-hosted by the Kyoto City Water Supply and Sewage Bureau, is making use of a new, grittier location near the Lake Biwa Canal Museum in Okazaki. The Biwako Canal, built to carry water over the Eastern Mountains from Lake Biwa to Kyoto, was one of the largest engineering projects of the Meiji Period. Thanks to it, Kyoto, having lost its status as a seat of government, was able to regain its footing as a center of trade and industry. But the city already had a source of water: its infamous bonchi (“basin”) topology, endlessly cited by locals as the reason for Kyoto’s hot humid summers and bone-chilling winters, is the result, as Noriko Matsuda notes in her essay at the end of the catalogue, of the fact that it sits atop an aquifer equal in volume to the water contained in Lake Biwa. “Jifei Kyoto” (“is/is not Kyoto”) pays tribute to this source of pure, sweet water – and its importance to the arts, sake-brewing, and gastronomy of the city. Even today, tea masters and coffeeshop owners line up to draw water from one of Kyoto’s famous old wells. Far inland, Kyoto is borne up and nourished by this vast, underground sea. The exhibition, as John Einarsen comments, is a “tour de force,” as much “experience” as exhibition. While at some of the venues, the scenography threatens to overwhelm photos themselves, in this case the photographers’ art has achieved a perfect fusion of subject and setting.

In addition to the “official” Kyotographie shows mentioned above, over 60 other “KG+” (associated) shows are currently open around town, including the well-established Shitsuraiten, now in its 7th iteration at The Terminal Kyoto, where John’s work is also featured, along with photographic installations by KJ contributors Tomas Svab and Lane Diko, and works by other artists. www.facebook.com/theterminal02/videos/1293488977736548/

Susan Pavloska, KJ’s Associate Editor, has seen all the KG shows for eight of the nine years since its inception.

All photos from KG shows ©︎ by Takeshi Asano

KG+ photo by John Einarsen