by Susan Pavloska

KYOTOGRAPHIE 2022 “One”

The KYOTOGRAPHIE International Photography Festival carried on even during the darkest days of COVID. Now back in its usual springtime time slot, its 10-year anniversary has attracted the largest crowds ever – even without tourists from outside Japan.

At the beginning, the appearance of a red KYOTOGRAPHIE banner outside front gates around the city was of special interest to longtime Kyoto dwellers (“Really? We can go in THERE?”). KG billed itself as a “handmade festival” with a distinctive Gallic bent thanks to co-founder Lucille Reyboz – but it soon hit a longer stride. Who can forget the “Mars” Xavier Barral/Takatani Shiro collaboration in the Kyoto Museum Annex, the two simultaneous Sarah Moon shows, and, in that Wonder Year – 2018, Jean-Paul Goude’s circulating, singing Sirens, Lauren Greenfield in the cavernous basement of the Kyoto Shimbun, and Alberto Garcia-Alix in the crumbling ice factory. Also, during the two years Japan was cut off from the rest of the world by COVID, Marie Liesse’s photographs for the visually challenged – and “Echo of 2011,” the moving quintet of memorials to the Triple Disaster, shown in Nijo Castle, among many others? Big or small, quiet or blockbuster, at its best, KG shows were always more than a little disturbing. Now, as it goes into its second decade, it is using that ability in order to play a more active role.

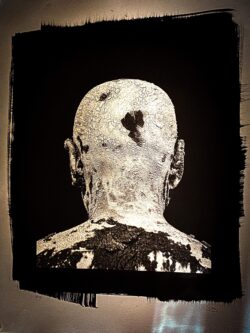

Kyoto is a city of Zen, but it is also a city of artisans, artists and art galleries – so it is not surprising to know that the festival had its origins at a former textile-weaving facility on Muromachi Street. In an essay in the current catalogue, KG’s other co-founder , Nakanishi Yusuke, reveals that the idea of the festival arose during a Butoh performance that he attended at Kondaya Genbei, the headquarters of the venerable obi-weaving concern that has served as a KG venue every year since the festival’s founding in 2013. He tells how renowned Spanish photographer Isabel Munoz was “deeply moved by the Kondaya textiles and the antique Japanese fabrics” the proprietor, Yamaguchi Gembei (see KJ#100), showed her when she held her 2017 exhibition, “Family Album / Love and Ecstasy” at his Kurogura gallery. The following year Munoz, Genbei, the dancer, Tanaka Min, and deep-sea diver/photographer Futaki Ai travelled to Kondaya’s mud-dyeing facility on Amami Oshima to collaborate on the current exhibition, which juxtaposes Munoz’s photographs and videos of the landscape, Tanaka dancing in the sea, and a mud-encrusted Genbei with examples of Kondaya’s precious mud-dyed textiles. Up in the tower are three incredible obi woven out of filaments made from Munoz’s photographs platinum printed on thin gampi (“gooseskin”) paper.

Writing in their preface to the first KG catalogue, Reyboz and Nakanishi averred that “KYOTOGRAPHIE’s intention was always to stage the work in the shrines, temples, machiyas, tea houses and other emblematic locations of the city. But by using scenographers and designers to ensure that the photography and the venues will each work to enhance the other, it was our hope that by engaging the participation of Kyoto’s traditional artisans, a broader spectrum of Kyoto society will feel that this is truly their festival.” The creative fusion we are seeing after ten years seems to confirm their vision.

Textiles, fashion, the lucrative “rag trade” and photography are of course deeply connected. In the recent “Billionaire” issue of the New York Times Magazine, Chief Fashion Critic Vanessa Friedman points out that despite it being “low tech or even old-fashioned,” fashion is a “world-straddling industry that has its tentacles in everyone’s lives.” The richest people in Europe, Spain, Japan, and Sweden are all owners of fashion brands (LVMH, Zara, Uniqlo, H&M, respectively). Chanel Japan, under the directorship of Richard Colasse, has supported KG from the beginning, and over the years the festival has featured exhibitions by NAOKI, Lillian Bassman, Conde Nast, and Frank Horvat. This year KG features elegantly-realized exhibitions by not one, but two fashion photographers. The artistic talents of both Irving Penn and Guy Bourdin were recognized early on in their careers. With Vogue magazine bankrolling them, both enjoyed extraordinary, but not unlimited, artistic freedom.

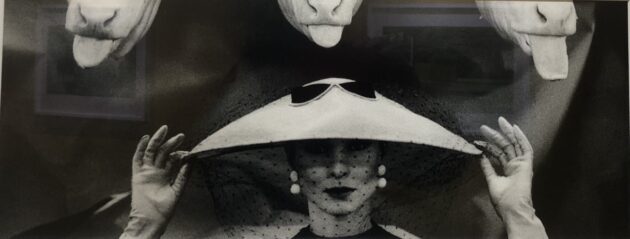

A student of the American surrealist Man Ray, Bourdin caught the attention of Vogue’s visually-sophisticated editors and readers with his photograph of a woman modeling a hat in the company of three severed cows’ heads in Rungis Market. Another influence was the films of Alfred Hitchcock as evidenced by his shots of tarted-up, wholesome-looking farm girls posing in tableaux that resemble frames clipped from a Hollywood thriller. Although images of dead and dismembered models are not uncommon in advertising, especially during this time, the shots featured in the exhibition were apparently selected by longtime KG collaborator curator India Dhargalkar from Bourdin’s archives, and not printed in the magazine.

Ten years older than Bourdin, Irving Penn studied design with Alexy Brodovitch and travelled in Latin America before going to work for American Vogue in 1943, marking the start of a career that spanned seventy years. With access to the best cameras, assistants, locations, and processes that money could buy, Penn produced an extraordinary body of work, expertly curated here by another longtime KG collaborator, Simon Baker. Before, after, and in between his fashion shoots and absolutely brilliant portraits of famous people, Penn refreshed himself by applying his considerable skills to unglamorous subjects such as portraits of ordinary people, and still lifes of shop windows, peeling walls, and cigarette butts and giving them an ultra-luxe platinum palladium print treatment. An extraordinary series of nudes he executed in 1949, the year he married Lisa Fonssagives, “the first supermodel,” was suppressed by Vogue magazine, and it is not hard to see why. The images depict a woman with a body straight out of a Philip Roth novel, a naked depiction of what men actually want, as opposed to what they are supposed to want, according to fashion magazines.

Which brings us to this year’s festival-within-a-festival, “10/10: Celebrating Contemporary Japanese Women Photographers.” Though one-half of its directorship is non-male and non-Japanese, KG has never sought gender or geopolitical parity. Instead, its lineup has reflected the general state of photography worldwide, past and present, which is mostly male, mostly white, and mostly non-Japanese. One exception is its promotion of work by African photographers. Reyboz spent her formative years in Mali and later, lived in Benin, and from the beginning, one of the distinctive features of the festival has been the prominent place it gives to photographers from the African continent. The very first festival features the Malian photographer, Malick Sidibé in the central Museum of Kyoto Annex exhibition space. Over the years, the festival has featured the work of J.D. Okhai Ojeikere (Nigeria), Badouin Mouanda (Congo), Zanele Muholi (South Africa), Romuald Hazoume (Benin), Omar Victor Diop (Senegal), Ngadi Smart (Sierra Leon).

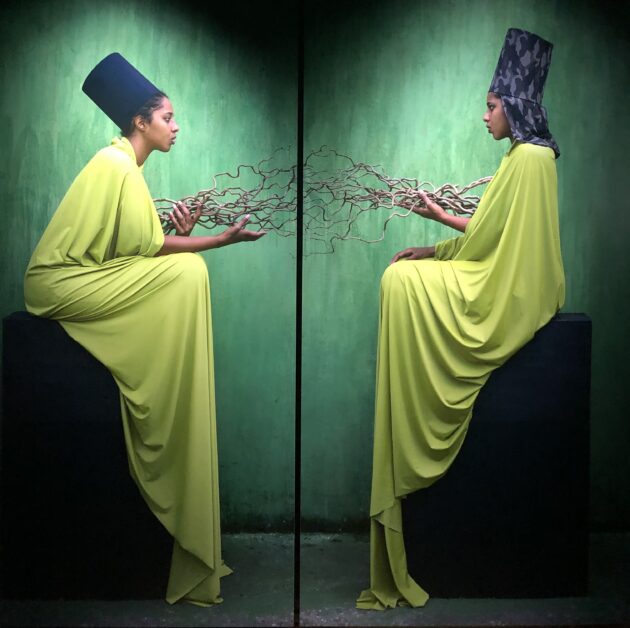

This year features the work of the young Ghanian photographer, Prince Gyasi, at Sfera in Gion and multimedia artist Maimouna Guerresi, who is of Italian and Senegalese origin at Shimadai. Shortly after Reyboz discovered Gyasi’s richly-saturated iPhone images while doing a search on social media, he was also courted by supermodel Naomi Campbell. Some of the work he did for her is on display on Asphodel’s second floor. The work of both artists, which is in many ways very different, is characterized by rich, saturated color and shows an Africa that far from being “one of the dark places of the earth,” is overflowing with a vibrant, spiritual power.

Although KG has not had a particular focus on gender, over these past 10 years its program has included many women photographers, including a wide variety of Japanese women working in the field: fine art photographers such as Takizawa Akiko (2014), Yoshida Kimiko (2015), Koga Eriko (2016), Miyazaki Izumi (2018), Katayama Mari (2020) and inri, who was featured twice along with her photographic partner-husband RongRong (2015, 2021); as well as photojournalists Yamashiro Chikako(2017) and Morita Tomomi (2018), the latter emphasizing women’s common stake in environmental issues, a major intersection with the continuing concern of the festival as a whole, as seen in the installations by Samuel Bollendorff at the Biwako Canal Museum this year. In contrast, over the years the festival has given international exposure (or re-exposure) to a relatively small number of Japanese male photographic “masters,” including Hosoe Eikoh (2013), Araki Nobuyoshi (2017), Fukase Masahiro ((2018), Kai Fusayoshi (2020), and the subject of this year’s exhibition at Ryosokuin, Narahara Ikko.

The “10/10: Celebrating Contemporary Japanese Women Photographers” exhibition follows up on last autumn’s underwhelming exhibition of five French women photographers at the Hosoo Museum. This year, Reyboz and Nakanishi curated the exhibition in collaboration with independent curator and historian Pauline Vermare, who is publishing a book on the topic. Conceptualizing the exhibition not as a group show but as “symphony,” Nakanishi says that the idea was to “create a strong effect that had never been witnessed before.” However, in fact, as Mariko Takeuchi points out, the current exhibition should be viewed against the backdrop of the previous generation of internationally-known Japanese women photographers, dubbed onna no ko shashinka or “girly photographers” by one male critic, who flourished in the decades between the collapse of the economic bubble and the rise of social media (an era for which the current generation of 20-somethings seems to have a distinct feeling of nostalgia). Feminist in impulse if not exactly in execution, photographers such as Nagashima Yurie, Hiromix, Ninagawa Mika and others used their point-and-shoot cameras to show themselves just having fun, pushing back against the objectifying gaze of the previous generations of mainly male photographers, who alternately flattered them and sneered at them for their lack of technical expertise. The ten Japanese women photographers in this exhibition share the common goal of stepping in to fill the “representation gap” in Japanese public discourse.

The exhibition occupies a “black floor” and a “white floor” in the Hosoo Museum’s splendid building on Aneyakoji Street. The scale of the exhibitions, which consist of a single narrow room or more frequently, a warren of smaller rooms, gives it an intimate feel, which heighten the effect made by two of the installations on the upper floor, which feature open windows. The first exhibition, “New Skin” by Hosokura Mayumi, projects two “numerical collages” of images from gay men’s magazines and sculptures from art museums. The collages dismember, pixelate, and distort these exaltations of the male form, rendering them unrecognizable.

The subject of “Zaido,” by award-winning photographer Chikura Hikari, is a 1300-year-old festival that takes place during New Year’s in the remote village in northeast Japan where her recently-deceased father once lived. The area’s wintry landscape, the festival participants, and the interiors of homes are printed on vertical banners and single long scrolls in appropriately subdued colors. Chikura said that documenting the festival, which could be wiped out by another tsunami at any time, was her way of honoring her father’s life.

Suzuki Mayumi, also from Tohoku, was chosen on the basis of her photobook, The Restoration Will, about the devastation of her family in the 2011 tsunami. However, for this exhibition she decided to present a series she had been working on after giving up on IVF treatments in 2020. Entitled “HOJO,” or “Fertility,” the origin of the series was in a two-pronged carrot she found in the uri-nokori unsold vegetable bin at a supermarket, which struck her as a metaphor for her own feelings of being unwanted and worthless as a woman who was unable to bear children. Taking it home, she “tenderly” placed a basil leaf on top of it and photographed it. The other photos in the series consist of nude self-portraits taken with long exposures recalling the countless hours spent waiting around in clinics, along with echograms and shots of other vegetables looking like diseased body parts – all symbolizing the ikizurashisa of being a woman in a culture where infertility is not talked about and inordinate value is placed on women’s reproductive ability at the expense of other capacities.

Iwane Ai traveled to northern Japan during the darkest days of the pandemic to photograph cherry blossoms in a place where the “boundary between human and nature is blurred.” Her installation also includes a slide show about her sister who died 15 years ago during cherry blossom time as well as a film about the family graves of Japanese Americans on the Big Island of Hawai’i which were inundated by lava flows. In all these works, beauty has a sinister aspect, as represented by the devil and fox masks in some of the photographs.

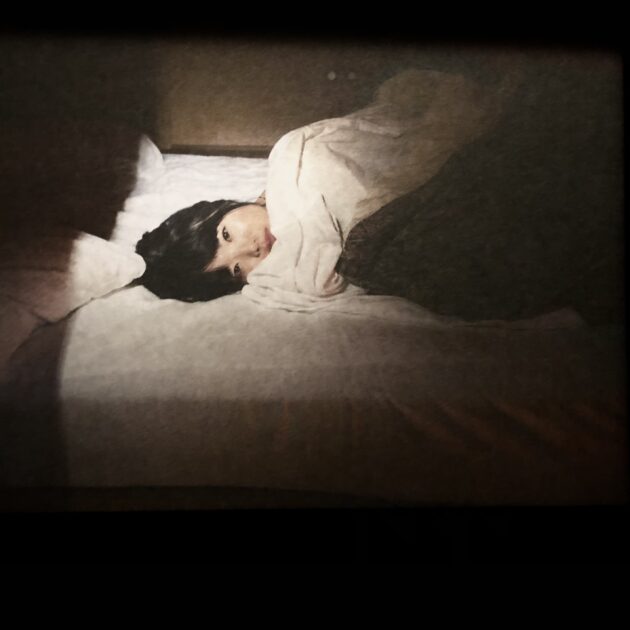

In “Die of Love,” the final exhibition on the black floor, Tonomura Hideka photographs a model in a manner reminiscent of stills from a movie. In the initial frames she is heavily made up and clothed in sequined evening wear, recalling Tonomura’s time working as a hostess in Kabuki-cho – the colors lurid and out of focus. In the later photos the model is naked in lying in bed in various poses. Read through the lens of Tonomura’s later work (on display at Sfera in Gion), the series also seems to be protesting against the way that women are valued as sexual objects at the expense of the other aspects of their being. She began “Shining Woman Project” after starting treatment for cervical cancer. Putting out a call on Instagram recruiting other women who were being treated for gynecological cancers to have their portraits taken, she was surprised when the women spontaneously asked her to shoot their scars and their disfigurements. Inspired by their rebellion against a culture that views the loss of sexual characteristics as a source of shame instead of the battle scars they are (“we are all survivors,” she says) Tonomura then had the idea of making the women’s portraits into placards to be carried through the streets of Kyoto from Gion to City Hall, arriving just in time for the KG Opening Ceremony.

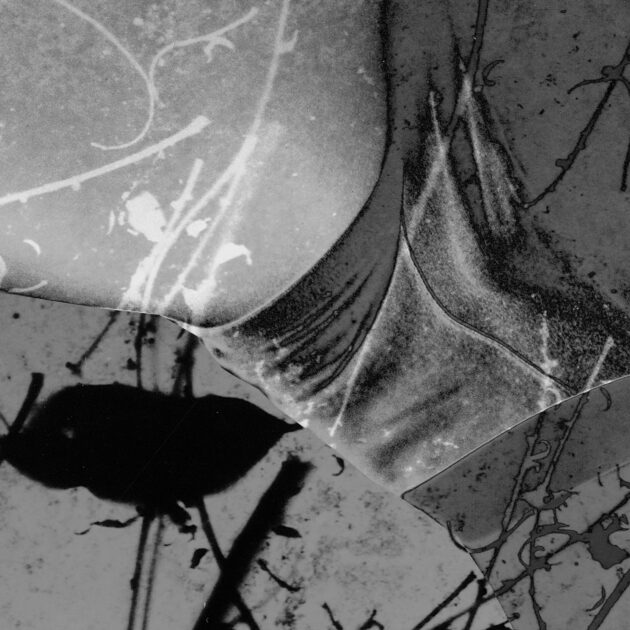

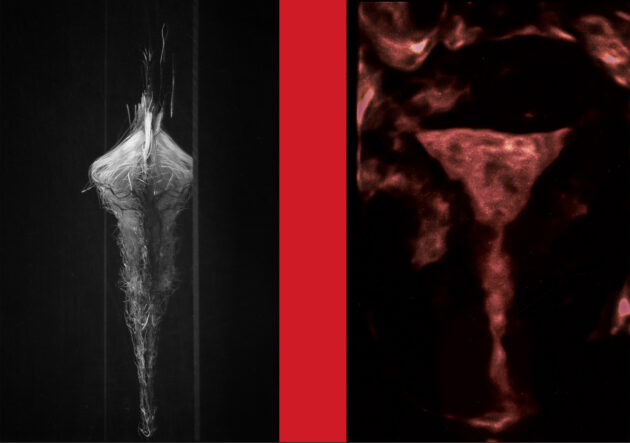

On the “white” floor, there are five more installations. First up, last year’s KG+ Select Grand Prize winner, Yoshida Tamaki, presents an expanded version of her series, “Negative Ecology.” While working as a commercial photographer, Yoshida began producing artworks using a thermographic camera. While developing a photograph of a deer, she accidentally contaminated the negative with a household substance. The luridly-colored result struck her as both beautiful and frightening, She began deliberately applying this technique, mixing shampoo, insecticide and detergent in with the chemicals to develop her wildlife photos – symbolically replicating the interaction between human-generated waste water and nature. The large format images, which are printed on upright glass panels and lit from behind, proceed from Yoshida’s own Tokyo neighborhood and bring us increasingly out into the wild through the open window on the building’s veranda, which was left open to the elements.

In “Eagle and Raven,” Inaoka Ariko (see KJ#101) expresses how her background as a member of one of Kyoto’s “old families” disposed her to pick up on the invisible bond between the identical twin sisters, while visiting Iceland during her time working as a commercial photographer in New York City. Returning each summer, she photographed the girls in various locations up until they reached the cusp of maturity. The pastel, softly-focused photos are hung framed in a dainty, wall-papered alcove and a circular gallery recalling the grandeur of the Icelandic landscape.

In the neighboring section, photojournalist Hayashi Noriko documents her twelve trips to North Korea since 2013 made in order to visit eight of the 1,800 “Japanese Wives” who had accompanied their Korean husbands during the massive, voluntary repatriation movement that took place between 1959 and 1984. They believed they would be able to go back and forth; permanently cut off from their families in Japan, they testify to the fact that love can have dire consequences. The installation, with its small, wallpapered rooms, hung with photos, artifacts, and family photos contributed by the women themselves, opens out to a window that frames a photograph of the sea, suggesting that urban domestic life in North Korea is not all that much different than life in Japan, after all.

Okabe Momo, in her guise as “Ilmatar,” a Finnish “virgin spirit and goddess of the air,” moves among the Japanese LGBTQ+ community and presents their proud portraits interspersed with still lifes composed of trash. As reticent in person as she is frank, even flaunting in her photographs, her large-format, neon-colored images evoke a future post-sexual world where sex is decoupled completely from its role in determining gender and even making babies.

The final series in the exhibition, Shimizu Harumi’s “Mutation/Creation,” also evinces as fascination with the non-conforming. Starting with an albino tanuki, she photographed a large variety of naturally occurring mutations (and one artificially created blue rose) of plants and animals, some one-off, others carefully hybridized, their potential freakishness offset by the bright Easter egg colors and the precise well-written explanations pinned to the opposite wall.

Taken as a whole, the exhibition emphasizes the diversity of ways of thinking and expression among the “Japanese contemporary women photographers.” While the previous generation survived by catering to the proclivities of a predominantly male group of critics, curators, and publishers, in 2022, this group of people has also become more diverse. In addition to the affirmation that many of these women received while studying or working abroad, KG has given them a supportive space in which to speak out. Spinning on its dual French/Japanese axis, KYOTOGRAPHIE has shown that it is not afraid to break taboos, giving us scenes of sublime beauty but also compelling us look at what we would rather not see. In a culture where activism has been given a bad name, KYOTOGRAPHIE stands out as an event where art transcends mere self-expression and becomes a means to connect with others.

Next year, KYOTOGRAPHIE has even more interactions in store. We can’t wait to see what they come up with next.

Susan Pavloska, KJ’s Associate Editor, has seen all of the KG shows in the ten years since its inception.