interview by Susan Pavloska and John Einarsen

[N]ow surging into its third year, Kyotographie is a Kyoto-wide photography festival of a scale unparalleled in Japan. Its open, ground-breaking approach to photography and its presentation allows the public to engage with superb artworks while exploring Kyoto’s hidden and not-so hidden spaces, among venues ranging from private residences to temples, decommissioned schools, and a Meiji-period bank. In spring 2014, Kyotographie’s “2nd edition” featured 34 artists from nine countries in 13 main exhibitions in 15 venues, and attracted more than 38,000 visitors. In addition, 34 public events were held and 51 satellite exhibits took place across the city.

This dynamic relationship between photographic art, innovative space design and the city of Kyoto has much to do with the artistic background and vision of its two passionate founders and directors, photographerLucille Reyboz and light artist Yusuke Nakanishi. We met them last October, freshly back from a trip to New York, having just finalized the contents for the 3rd edition of Kyotographie, which will be held from April 18th to May 10th, 2015. The theme this year will be TRIBE and feature 14 main exhibitions and around 35 satellite exhibits.

John Einarsen: Tell us a little of your background, how you became artists…

Yusuke Nakanishi: My profession is lighting direction for movies and theater, dance performances, and concerts. I do lighting for spaces, interiors, and installations as my own artwork. I have traveled all over the world, and learned about lighting from my journeys. When I’m travelling, I don’t take pictures—I just look at the light.

Susan Pavloska: Where did you see the most interesting light?

Y: Every country has different light. For example, Rio de Janeiro has big waves that strike the rocks, making a sort of fine mist; the light through this mist is so beautiful. Also the light over the desert makes magic colors when the sun goes down, when the sky still has light. Have you been to the Uyuni salt lake in Bolivia? It’s one hundred kilometers square. When the sun goes down and the moon comes up, you can see this white canvas—patterns become visible, changing color, from blue or purple, orange, getting white, and again changing color, like a beautiful light show. I use these memories in my work.

Lucille Reyboz: I began photography with my father when I was around 14. He was a good amateur and we had a darkroom at home. I started my career shooting covers for jazz musicians and African musicians for Blue Note records and Verve. Because I grew up in Africa, I had all these connections; I started to work with Salif Keita, the famous singer from Mali. I came to Japan the first time with Salif Keita as he was participating in Sakamoto Ryuchi’s opera, Life—and that’s how I discovered Japan and started to take pictures here. Over time I did fewer covers and focused more on researching animism in Africa and Shinto in Japan.

S: What were the results of your research?

L: I published a photography book Batammaba: bâtisseurs d’univers by Gallimard on an animist tribe, the Tamberma of north Togo, focusing on their unique architecture and lifestyle. In Japan, I worked on a series that resulted in another photography book, Source, by La Martinière /Abrams. This work centered around the special relationship Japanese people have with nature—primarily the onsen culture.

S: How old were you when you left Africa?

L: I was four when I was living in Bamako with my parents and then came back to visit Senegal in my teenage years. I came back by myself to Mali when I was 18 and decided to live there for a while. Later I travelled to Burkina-Faso, Benin, and then later Togo where I lived for a time with the Tamberma community. I miss the African way of living; the relation to the people, to the world and to nature is still so strong and pure there.

J: So how did you two meet?

L: It was just before the [3/11] earthquake. I wanted to do a photo series based on traditional Japanese ghost stories. I was living in Yotsuya, an area in Tokyo said to be inhabited by obake [ghosts]. We had some friends in common and we met by chance at a party. I was preparing for this shoot, and I knew he was a lighting artist, so I asked Yusuke if he would consider collaborating. By chance he was reading exactly the same book as I was—Kwaidan, a book of Japanese ghost stories written by Lafcadio Hearn.

We both felt it was critical to create an atmosphere, lighting was extremely important. Usually I go with natural light, but this time I knew collaborating with someone like Yusuke was essential for the series.

Y: When people die, their tamashi [spirit] leaves their body; it is like a glowing sphere of light. So I made this “fireball” to represent the spirit. From this “fireball” in the shoot I made a special light, “Tamashi.”

L: I used film and we limited ourselves to just one shot for each scene. That is the miracle of a good picture—something that’s given to you, something beyond your control. We have lost this with digital. We shoot too much. I use a Hasselblad and a shoot takes time to set up—it is almost a ritual in itself. It is a very intimate way of shooting—at first you must face and interact with the subject before looking down into the viewfinder, so there is time to have an exchange—we make the photograph together.

Y: Kwaidan is all connected to nature. In most Japanese ghost stories humans transform into nature and nature transforms into humans. There is a connection between nature and humans. Then, when the earthquake struck and the Fukushima disaster ensued I thought that there must be something amiss with our relationship to the natural world. Japanese people used to have such a strong connection with nature, but perhaps we have forgotten to maintain respect for her. Maybe it is wrong to use something that is beyond our power to control. And nuclear power is beyond our power to control.

L: We moved to Kyoto after the earthquake and finished our Kyo-kaï series there. It was so refreshing and inspiring to explore Kyoto together on our bicycles. It was a real time of change.

J: What was the inspiration for Kyotographie? Why is Kyoto especially suited to your vision?

Y: Kyo-kaï was exhibited in Paris in June 2011. At this time the Arles Photo Festival [Les Rencontres d’Arles] was on. Lucille had gone many times before, but for me it was my first time. It was such a sensational festival—a photography matsuri! I was surprised there was no information about it in Japan. I realized we had to make something in Japan for Japanese photographers to connect and to give them a stage to show their work and be recognized in their own country and abroad.

I had always come to Kyoto as a tourist or for work, but moving here was very different. As we rode bicycles through the streets, we saw many beautiful buildings, so we thought if we held a photo festival in this city it would be interesting for people to see exhibitions but at the same time see the city from a new perspective. That was really the start.

J: How did you succeed? What is your secret?

L: Luckily, we began as soon as we arrived in Kyoto. Many people told us, “You cannot do that, Kyoto is so difficult.” We kept a certain distance when we first moved here—because we were both strangers in a way. Yet we were very fresh and full of enthusiasm and passion, so we just began.

Y: As strangers it is easier for us to make something new for Kyoto. Even if Kyoto people want to change they are restrained because of Kyoto’s long history and traditions. We needed to find a value that we all shared. What that was, we realized, is “quality.” So we are trying to create a quality photographic event in Kyoto.

L: Also Kyoto people are already excellent in what they do so if you don’t bring something completely different, which is not part of traditional Kyoto, it’s almost impossible to succeed.

J: What did you learn most from the first edition of Kyotographie?

L: So many things! We never did anything like this before, so we were making and learning at the same time.

Y: For example, the first time we asked Kyoto people to use a house or other venue, they were cautious. It took time to gain their confidence.

L: In Japan, and especially in Kyoto, “new” is sometimes equated with being in opposition to tradition and custom. So at first it was very hard to convince people. But even now, when we approach families, even if they have seen the festival, as Yusuke said, they are often still reluctant. So we have to explain and justify what we want to do and then it might work. Luckily there are many great people in Kyoto.

Y: If we go back to Japanese roots and see that Kyoto is at the essence of Japanese culture and history, we understand—ah, that’s Japan. What’s important is to respect Kyoto people, what they think, and what they keep.

S: You have some fantastic sponsors, like Chanel. Is that something else that impresses them?

L: Of course to have Chanel as a sponsor gave them more confidence in our project.

Y: Kyoto people respect quality brands. They also appreciate the craftsmanship and attention to small detail.

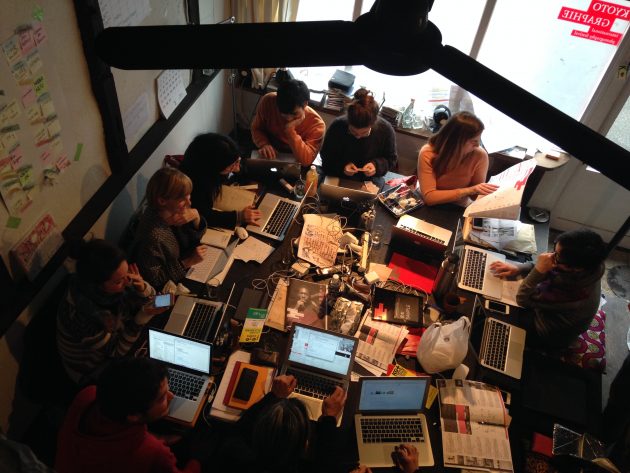

L: We collaborate with our sponsors to find a suitable match creating mutal benefit. We collaborate with our staff too—it’s really part of Kyotographie. In our office we just have one big table. We put the festival together here—day by day, piece by piece.

J: To me what is amazing the way you envision the photography in the Kyoto spaces. For example, the diorama series in Kyoto Station. And the nuclear power plant landscapes at Shimogamo Shrine—I thought that was a creative act in itself, imagining it in that way instead of just presenting it in a gallery…

Y: We are artists, so we understand how a photographer might want to show his or her work in this kind of place. We need a story that connects the photographs and the venue.

From the start, I had really wanted to show Taishi Hirokawa’s nuclear power station landscape photography. They are beautifully printed black and white photographs. They are quiet but very scary. Since I believe we have to re-imagine what animism, Japanese animism, and the Japanese spirit are, I wanted to show these images in a shrine. I approached Shimogamo Shrine because it has a large forest and a sacred spring. I wanted our audience consider the question “What is nature?” I thought my idea would be impossible, but the shrine said yes to it. We are always challenged to create a resonance between the program and the venue.

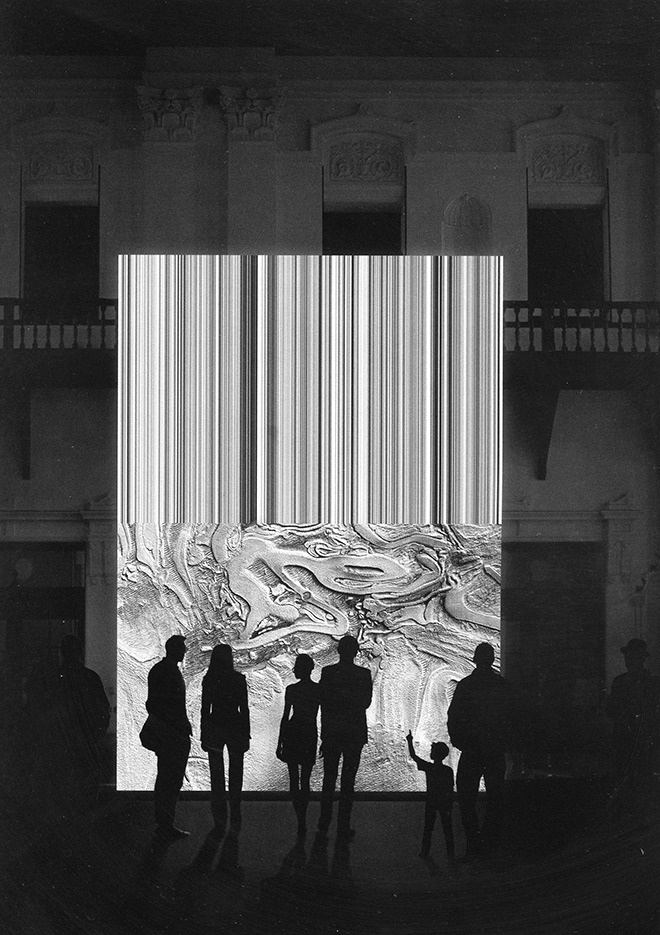

J: For the Mars photographs, you involved another artist, Shiro Takatani…

L: We invited this show from Arles, but we wanted to do something different with it.

Y: We decided to ask Takatani-san to make a video installation. He wanted to project the Martian landscapes on the ceiling, but the roof of that building, a Meiji-era bank, has skylights, which we weren’t allowed to change. So we had to completely alter our plans. We still hadn’t decided one month from the opening. Then I heard that Sony had just manufactured a large 4K LED display, a very thin panel that was scheduled to come out in April. So I ran up to Sony headquarters in Tokyo and said, “Let’s show this new product in Kyoto, because we have this festival, and this screen is perfect to show the quality of the tones in these black-and-white images.”

The Sony people were so surprised by the beautiful detail of the blacks, grays and whites of the Martian landscapes. They agreed to our proposal. However the display is made to be viewed horizontally. I wanted it to be vertical. Sony said this would be very difficult since they would then have to change the display’s programming for it to work this way. But the screen had to be vertical—all the Mars images were vertical—and we also wanted viewers to experience the images while lying down, looking up. So Sony changed the programming, while at the same time Takatani and his team worked on their own programming—all of this happening in that one month before the opening!

J: That was one of the most interesting things I have ever seen. What an experience!

Y: We are always giri-giri [tight] because making fifteen venues and fifteen programs [in the first edition] is crazy.

L: In Africa we say, there are no problems, there are only solutions. That’s really our feeling with this festival. We pull everyone together to make it happen, and in the end everyone is happy. For example, Sony was so grateful to Yusuke and Kyotographie that they were able to introduce their technology in this way. They collaborated again in Tokyo with Takatani—so this is also bringing them some new way of communicating. Kyotographie is a platform for experimentation—not only showing photographs, but for creating new installations.

S: Do the people who exhibit volunteer to let their work be exhibited?

L: Actually we proceed like most festivals around the world. We are not commercial—of course artists want to exhibit, and of course we produce everything. If they come from overseas we invite them and pay all expenses. It’s the same as Arles, where the artists are not paid to exhibit.

J: One of your goals is to make it a truly international…

L: We created it first for Japanese photographers, to give them a stage. Japan has this amazing culture of photography, but strangely people here rarely go to photographic exhibitions, and there’s no market. Japanese photographers do not sell in Japan. A few of them, Hosoe, Moriyama, Araki, they sell, obviously, but they sell mainly overseas. A few Japanese galleries, like Moriyama Daido’s, sell mainly to foreign collectors. Hopefully Japanese photographers can gain a greater following in their own country.

J: Do you think you’re succeeding?

L: I think so. Step by step we have started a movement. You can’t sell photographs if you don’t first teach people about them.

Y: That’s why we don’t use the “white cube”; we use Japanese houses, Western houses and contemporary spaces.

L: And also to close the distance between audience and artwork. We are convinced that by exhibiting in more familiar surroundings, we can bring photography to a larger audience. Photography is such an amazing medium—you don’t have any barrier of language, and yet we can communicate so many things through it. We didn’t want to create this festival for only “photography people”—we wanted to make it without limits of age, background, or culture.

J: How do you choose photographs?

Y: For the artwork, my main criterion is beauty. Even if an artist shows documentary work on an “ugly” subject such as violence, it still needs to catch the eye, to capture a point of view. Connecting one heart to one heart, one mind to one mind. You either create this bridge or you don’t.

L: I really believe that in life, it’s all about encounters—we meet photographs like we meet people. When we do the program selection we are very open. We go to meet people and to see exhibitions, and what makes us react is always connected with something happening in the world around us. We also want to show some shocking things, because that is how the world is now; it’s also the strength of the photograph.

J: We live in an age where images are everywhere and proliferating at mind-boggling speed. Most photographic images are now experienced online. As curators of photographic imagery how concerned are you with peoples’ ability to really take in an image, slowly and deeply?

L: First, I don’t like to be called a curator, I mean—we do work with curators, but we also work closely with the photographers in cases when there is no curator.

We are living in a very interesting time. As photographers we have experienced so much change, and of course the relation to the image is now so different from what it was. When photography was invented it started with glass negatives and film, and the technology has continued to change. We are now immersed in photographs.

I was with two agencies. Both had strong identities that centered on humanistic photography, and all their photographers had their own distinct identities. But in the last 15 years, big corporations have absorbed such independent photo agencies. Magazines have disappeared or gone to the web. Now, the new way of considering photography is as artwork, as is evident in events like Paris Photo.

With the Internet it’s crazy how many images we are consuming every day! Particularly so in Japan. So with Kyotographie, we thought it is time to make photography something special again, something unique and magical. That doesn’t mean we don’t have any interest in this new relationship and very intense, mass consumption of imagery; that’s also our world now. Some academics attack us a bit because we break from the very classic way of exhibiting photography. Photography is in motion all the time, yet that also gives us a lot of freedom in what we create.

We make “surroundings,” bring elements together and then open it up. We are more like conductors. We interact. We don’t have this academic background. Our way is spontaneous.

J: I can feel that.

L: We always turn to curators because we don’t have the background they do. We are fortunate to receive the advice of Simon Baker, Curator of Photography and International Art at Tate Modern, and directors of other established institutions. With their input, we can make something with balance and consistency.

Y: We want to surprise ourselves and our audience. We look for what is possible in photography. That’s why every year we change the venues.

L: Our biggest challenge is to keep Kyotographie fresh. Some venues have become part of the identity of the festival, and Kyoto is Kyoto. But we will still try to show something completely differently to maintain a sense of novelty year after year.

J: How big is your team?

Y: Quite small. It starts with the two of us, and then little by little we increase the number of staff since we don’t have a big budget. Three months before the festival we have ten people, but for now it’s only six.

L: We find sponsors and do content together. This year we are partnering with ICP [The International Center of Photography] in New York—that gives another international dimension to the festival. We are developing an educational program that will feature more workshops and some master classes.

Y: From overseas, the Japanese photographic world feels like a sakoku—“a closed country.” When we created Kyotographie, many museums and festivals contacted us because they wanted to connect with Japan but hadn’t known where to go. For example, we are now considering a cross-collaboration with the Arles festival.

J: Is there anything you can tell us about the third edition?

Y: This past year Kyotographie was about the environment, what exists around us, so next year we want to focus on what humans are. Our theme will be “Tribe,” but not in an ethnic sense—it’s more in the sense of a community that shares the same sense of values. There are many tribes now that are not related by blood or confined by national borders. Also there is much about racism.

L: It also touches the ritual practices of any kind of tribe. Our program is fixed now. We are really excited about it!

J: To me, one of the best things about Kyotographie is that it encourages people to create.

Y: We realized nothing is impossible. People always say, “That’s impossible.” We reply, “Of course, we are doing the impossible, we are challenging the impossible, making the impossible possible.” That’s our festival.