[S]udo Hisao’s latest sculpture, not yet dry, stands in his ceramic studio: a giant acorn, bursting with life, erotic tip pointing upwards. Around it, a snake is coiled protectively, its gaze unwavering, piercing, inscrutable. Though it is poised to fight if necessary, Sudo doesn’t think of the snake as attacking.

“Nature is not aggressive,” he says, explaining that while this species’ venom can be fatal, the snake is holistically beneficial to the ecosystem. The locals of Amami Oshima, where it is found, both fear and revere it, using its skin pattern as a weaving motif, to wear as a talisman.

Amami Oshima is one of the Ryukyu Islands, a long archipelago extending from southern Japan to northeastern Taiwan, consisting mostly of the exposed tops of submarine volcanic mountains. For the past decade, Sudo’s primary inspiration has been the ecology of this pristine island, which is mostly covered by rich, virgin forest.

“Amami Island is a prism through which I view the world and then reflect it in my work,” he says, his eyes sparkling.

Most of Sudo’s pieces are larger than life. He creates from a passion for life that accords a visceral energy to each of his sculptures. Their unexpected associations draw us in to marvel intuitively at the endless overlapping of all living creatures. Sometimes dark, at times light, they are always playful. Sudo believes that through inter-relating with the natural world we can rediscover a balance that shifts us away from our errant sense of being the center of the universe.

“I look for nexus points where processes or life forms seem to overlap. They are sometimes difficult to find, but when I locate them, that is where I begin my work.”

As an artist, he is a mediator between the realm of nature and the imagination. His pieces, like life, are never static; there is always a sense of process or transformation. Some of his work is direct, like the black hare opening its heart, urging us to reciprocate. The ancient, rare and endangered amami-no-kurousagi is endemic to Amami and just one other island. It is designated as a national treasure; one of only three such species that still exist.

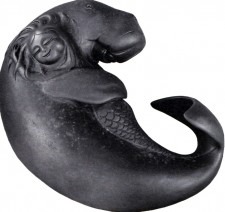

Another piece reflecting the ever-shifting faces of nature is based on Odoru Kenmun, a forest sprite in Amami mythology. This creature has the magical ability to shape light on his fingers when fishing, and playfully entices humans to play at sumo with him. Sudo has given Kenmun three faces: on one side a traditional comedic mask called Hyotoko; on another, the beaming Ebisu, one of the seven Gods of Good Fortune, who favours fisherman with big catches. The last is an oni, a fearful demon.

“By watching nature closely, one begins to feel the essence, the life force. I believe in animism, and in the interconnectedness of all living creatures. By looking at the patterns in nature, sometimes I find answers and sometimes questions. I am always thinking about nature, not always understanding but always observing and following the trails that crisscross.

“I make connections with the natural world and then my ceramic works are a way of connecting with other people. I hope that my sculptures are a reminder to relate to life and nature in a way that we have forgotten. My art arises where language ends. Sometimes words have the power to emphasize one meaning to the exclusion of others. I want people to be free to find their own interpretation, make their own connections.”

An insect called mai mai kaburi and a snail seem locked in a sensual embrace; looking more closely, one realizes that the snail is being eaten.

“All the world is developing; some aspects are dying while others are renewing. To live and to die are the same. From birth the process of death begins; front and back are the same.” From his studio storeroom, Sudo brings out another piece, a peach pit greatly enlarged. One can move around it as if orbiting a planet. Moving closer, its details seem chaotic but as one pulls back, patterns emerge.

“This seeming chaos can be confusing yet is also the basis of a greater stability and peace. Diversity is intrinsic to peace. In the same way, life may seem chaotic on the surface but it is this very interconnected chaos that makes up larger patterns of structure and order.”

Since Sudo Hisao’s sculptures are imbued with immensely detailed observation, samples from nature are essential. The studio is filled with objects he’s collected or been given by friends who work in fields of conservation and ecology. Skulls ranging from sea animals to land mammals hang from the walls; landmarks on the journey of how species have evolved, physically and consciously. Sudo speaks of how malleable and adaptable bone can be, often more flexible than the thoughts it houses.

“I am interested in the origins and evolution of the human race. We started in Africa and that is where both our noblest and basest traits also began.”

“I am interested in the origins and evolution of the human race. We started in Africa and that is where both our noblest and basest traits also began.”

Sudo traveled to Tanzania last year, to one of the places where the oldest known hominid fossils have been unearthed. “I wanted to stand in the same place as our early ancestors did, feel the sun and the wind, breathe the air, smell the fragrance.”

He opens drawers, revealing a small collection of ancient tools. “Where did art begin? From earliest times, hunting and carving tools were decorated. They did not need to be as beautiful as they were, but the desire to create comes from an innate sense of beauty.”

[F]or the past 24 years Sudo has been making his ceramic sculptures in a valley near Sonobe, a town north-east of Kyoto. Silence pervades, save for the wind rippling the grass between the rice paddies that rise up in terraces to forested hills. He lives with his wife and teenage son; a daughter studies art in Kyoto. Part of his time is spent farming his rice paddy and vegetable gardens, in a closely-knit community. And when he is not working the earth, he is in his studio working clay.

The story of how his art has evolved reflects the maturation of his relationship with nature. In his early 20’s, Sudo started his career as a commercial photographer. He became dissatisfied with the medium, though, because he disliked having to wait for the right shot. He wanted a more active role in the creative process, to be able to choose the end, and more, to touch his work.

Then he met Yoshimura Shunichi, a ceramics master whose area of specialization was the potential of materials. Yoshimura had written books based on his extensive experimentation with varieties of clay and glazes and ranges of firing temperatures. For six years Sudo studied pottery under him, continuing to work as a freelance photographer and also taking shifts in a grocery store. Yoshimura constantly challenged his students to experiment, allowing them free creative rein.

Watching the way his sensei lived and worked, his acute observation and mindfulness, the way he developed theories and then always tested them, Sudo was greatly inspired. In the early stages of his career he made functional ceramics, yet wove mythological elements into their design. Gradually he moved towards making sculptures.

An exhibition in Sonobe in 1984 was a turning point. He used two spaces, one a traditional tatami room filled with utile ceramic ware, the other a modern room showing a series of his early sculptures inspired by nature: a range of frogs in the process of moving through a leap; two snails looking at a real snail shell with the same spiral design as their own.

The following year Sudo held an exhibition in Tokyo, that he called Nuclear Zoo. So that people could grasp the scale of global nuclear production, he made 53,000 miniature warheads; his tally mirrored the actual number of nuclear weapons accounted for in the world at that time. Along with these, he made small-scale animal sculptures; stark, frozen in position, offset against the whiteness of a nuclear winter. Out of this exhibition he created a book of photographs, accompanied by the poems of Kawasaki Hiroshi. One striking line: ‘They say dogs and horses also dream. I hope we humans are not in their nightmares.’

For the past six years, Sudo has been working on his Amami series; he expects that this will culminate in a show two years from now, and is looking for a suitable exhibition space.

To my way of thinking, the extinction of flora and fauna in the outer world corresponds to the extinction of many unique forms within ourselves. The time has come for us to reconsider our relationship with nature. It may be too late, but in order to move from a jealous co-existence to a true co- living, we need to enrich the ecosystem within ourselves, which is also in danger.

All sorts of creatures riding the hazy border between life and death, heedless of our human time, coming back and forth leisurely across the border of fantasy and reality— they have been at the heart of the struggle between people and nature all along. I have chosen as my subjects these creatures abused and neglected by the dream of progress. Each is like a discarded aspect of humanity, for we are a part of the natural world. By rediscovering these missing faces from nature, we rediscover the lost or dimmed sides of ourselves.— Sudo Hisao, 2000

[H]ow remarkable it is that a visionary artist of Sudo’s talent is so little known! His work possesses spirit which surpasses mere mastery of technique and skill. When one lives purposefully, one is always changing, one’s heart and mind and spirit. Even he can’t predict what his future work will be; it will arise as the inspiration takes him.

“I don’t like ‘why’ and ‘because.’ Instead I want to play, always to keep playing.”

One sculpture is a ball of snakes, grapes and frogs, all massed together. “When you look very closely,” he asks, “how do you tell where plants end and animals begin?”.

One wonders, looking at Sudo’s work, where do we begin and end? Difficult to even say where the body leaves off — is it at the tip of the finger or in the DNA? His vision extends beyond his work towards a Gaian politik; the flesh of one’s body is the flesh of the earth is the flesh of experience.

In another sculpture, three large tomes are piled on top of each other. The top one, a Bible, is slowly being eaten away by spores growing from its covers. One of the first and simplest of species is regenerating.

“Cycles of nature will prevail, even if man becomes extinct and all records and traces of human civilization vanish. Nature will continue to rejuvenate, new species will grow.”