[E]ven before the tourist boom, Kyoto had an omote, or hospitable face, so carefully tended that foreigners often weren’t aware of the existence of its fiercely-guarded ura, especially in those central Kyoto neighborhoods hosting the Gion Festival each July. Imagine the surprise then, that “outsiders,” meaning anyone with less than five generations’ residency, must have felt one fine spring day in 2013, when red banners suddenly appeared outside venerable machiya, forbidden temples, and even the off-limits sections of Nijo Castle, signaling that for the price of a ticket, one was free to enter? And, once inside, imagine finding world standard, creatively-mounted exhibitions of photographic images, accessible to all, despite linguistic and social barriers? That was the beginning of KYOTOGRAPHIE for the average Kyoto-dweller.

That first year, the twelve exhibition venues included Kurogura, an imposing black storehouse in the interior of the equally-imposing headquarters of the Kondaya Genbei obi (kimono sash) company on Muromachi Street, ASPHODEL, on the premises of the venerable Tomiyo teahouse in Gion, and the former Kyoto branch of the Bank of Japan, a Meiji-period Western-style brick building incorporated into the Museum of Kyoto on Sanjo Street. The number of venues is multiplied by the smaller satellite KG+ exhibitions, 52 this year, taking place mainly outside the central Gion Festival area. In the beginning these featured mainly local artists, but now are quite competitive, drawing participants from all over Japan, Europe and elsewhere in Asia.

The theme of this year’s festival is “Love,” a sentiment that is seemingly-universal yet highly-fraught in ways that vary widely from culture to culture. The festival’s organizers do not try to reconcile the differences but rather lay out the debate in spatial and visual terms.

Nighttown Gion is an appropriate setting for two of the festival’s splashiest offerings: Araki Nobuyoshi’s “A Desktop Love,” and Toilet Paper’s “Love is More.” In the latter, the Italian design company transforms ASPHODEL into an over-the-top love hotel where commercially-available images of beautiful models perform “perverse” acts. While a few of the exhibitions have viewer discretion warnings, this one, which does not, is the one exhibition I would not want my 16 year-old daughter to see. Across the river, in the newly-opened “Arts & gastronomy space,” FORUM KYOTO, the darkly funny self-portraits of South African artist/activist Zanele Muholi’s Somnyama Ngonyama (“Hail the Dark Lioness”) exemplify a black lesbian aesthetic that openly defies the exoticizing and fetishizing gaze.

Originally entitled “A Desktop Paradise,” Araki’s photographs reflect the musings of a shut-in (he recently underwent treatment for prostate cancer): a series of still lifes composed of the detritus that can be found in many urban dwellings: dead potted plants, folk art dolls, plastic figurines, and flowers. His obsessions soon reveal themselves: a dead cactus and a stone flower holder take on the configuration of a lingam and a yoni; naked dolls and plastic monsters pose like the porn actors relaxing between takes in Sophie Ebrard’s KG+ show at the Frank Work photo studio in Mibu. The venue, Ryosoku-in Temple, is not a strange place for such an exhibition if one is familiar with Araki’s masterpiece, Sentimental Journey, which was published together with Winter Journey in 1991. The first is a self-published love token for his wife, Yoko (like Rene Groebli, he took his camera on his honeymoon). The later work documents Yoko’s decline and death twenty years later from uterine cancer. The genius in both works is how in combining insouciance and restraint he manages to convey powerful feelings through visual means, without sentimentality. Nevertheless, he could not resist the urge to comment in words: he himself executed the calligraphy for the two hanging scrolls in this exhibition. The one in the garden teahouse reads “One, Two, Death,” which is a visual pun which also rhymes if read in English and Japanese.

The other big shows are on the west side of town. “Momento Mori,” Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs from the Peter Marino Collection is a well-balanced survey of his work displayed in a specially-constructed gallery in the Chikuin-no-Ma room of the main building of Kondaya Genbei. The fact that the photos cleared Japanese Customs unchallenged attests to Mapplethorpe’s iconic status. Admittedly, the most controversial ones are not included here, but Mapplethorpe’s images, composed in collaboration with his subjects, who are named, except in those cases where they did not wish to be, does succeed in showing how the gap between love and eros might be bridged.

While Mapplethorpe’s celebrity portraits of the 1980s are not included in the show, this lack is made up for by Arnold Newman’s “Masterclass,” in the grand kitchen of the Ninomaru Palace of Nijyo Castle, which was used as an exhibition space at the first KYOTOGRAPHIE. Contemporary examples of Newman’s experiments in “environmental” portraiture can be seen in Nomura Kanta’s KG+ images of the residents of Kyoto University’s decrepit Yoshida Dormitory, possibly the most exclusive and precarious exhibition space in this year’s festival.

Raphael Dallaporta’s spectacular 360-degree video installation of the Grotte Chauvet-Pont d’Arc in the Annex of the Museum of Kyoto is a love letter from 37,000 years ago. The cave paintings, which predate Lascaux by 20,000 years, show an uncanny sophistication, forcing us to rethink our conceptions of our remote ancestors. The video installation, complete with beanbag chairs and a soundscape by Hara Marihiko, echoes the ground-breaking Mars exhibition that took place in the same space three years ago.

This year’s theme is more directly addressed in some of the smaller shows. The construction site that is the stripped-down shell of the Shin-Puh-Kan within its steel mesh enclosure is the setting for two of the main shows, plus a number of KG+ shows and special events. Susan Barnett’s selection of eight outsized photographs of people promoting love on the back of their t-shirts is KYOTOGRAPHIE’s first outdoor installation. Inside is one of this year’s most talked-about shows: Yoshida Akihito’s photographs of his grandmother and his younger cousin Daiki, who was raised by her. The undercurrents of the loving intergenerational relationship that is documented along the curved inner walls build to a crescendo in the dark circular room at the center. Looking up at the dry leaves above, we suddenly shift from the photographer’s point of view to that of Daiki, who at the age of 23 committed suicide in the forest. His body was covered with falling leaves; his disappearance remained a mystery for almost a year. The installation drives home the point that while we most often associate love with joy, it is a burden as well.

Similarly, in the Shimadai Gallery on Oike Street, the alcove in which the central photograph of “Emmy’s World,” Hanne van der Woude’s record of a six-year intergenerational friendship, which shows Emmy and her husband, Ben, in bed together, is made to look like a giant bed. The rumpled sheets refer to the existence of physical love between people of all ages, but also Emmy’s turmoil: while Ben sleeps peacefully, her eyes are wide open, watchful, as she sees that he did not have long to live.

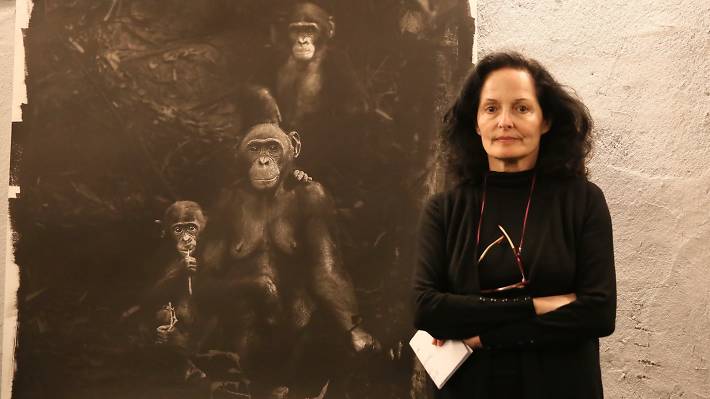

The exhibition of historical photographs from the Guimet Museum at the Toraya Gallery (near the Imperial Palace), while briskly noting that “love was not highly valued in the Confucian morality that prevailed in feudal Japan,” devotes itself mainly to the images of geisha and oiran produced for the 19th-century tourist trade (including those collected by Giada Ripa’s ancestor, Mathilde de Ruinart de la Tour, which form the basis of the Yokohama Project at Shimadai). Nevertheless, the exhibition ends with a portrait of an elderly couple, looking like two Takasago dolls, from the Noh play of the same name, sets of which are still sometimes given as wedding presents. The simple human feeling between them rivals that which is seen in Isabel Munoz’s gorilla Family Album at Kurogura.

Aikoku, “love of country,” is one of the few instances of the word “love” that can be used in everyday Japanese life without embarrassment. Two rooms in the Horikawa Oike Gallery, part of the Kyoto Municipal High School for the Arts, are devoted to the work of video artist Yamashiro Chikako celebrating nonviolent protest against the US military bases in her native Okinawa, while making efforts to prevent its tragic history from fading from the memory of future generations. The most recent of these, Mud Men, which caused a stir at the Aichi Triennial last year, is a fantasy in which two islands, Okinawa and Jeju in Korea, are connected to each other via a subterranean passageway, uniting them in their common experience of being squatted upon by military installations, forcing each into a state of precarity. The film ends with the Mud People (a derogatory term given by mainland Japanese to non-violent military base protestors) emerging into a field of Easter lilies. The sound of gunfire turns into the sound of hands clapping, a hopeful and positive image.

In many of the shows, there is a primitivistic ethos that is a reflection of political concerns about preservation and sustainability. In his KYOTOGRAPHIE exhibition, “Between Light and Darkness,” at Mumeisha, last year’s KG+ winner, Yan Kallen, uses a hand-made camera obscura to craft images of Kyoto artisans and their works. In the Noguchi Residence, Claire de Virieu’s black and white photographs, in “Nara: A Double Passion,” give landscape elements such as ponds, reeds, and rocks a dreamlike quality. This year’s KG+ winner, Morita Tomomi, whose show took place in the Everyday Life Study Room of the Junpu Elementary School, uses “Two Rivers” symbolic of the environmental problems during Japan’s period of high economic growth as the subject for his austere photographs.

Kyoto Journal’s own KG+ exhibition, at Gallery 108 in Shimogamo, features photographs from its 30-year publication history as well as a wide selection of back issues. Works by Young-Sook Park, Koo Bohnchang, Yoshinaga Masayuki, Yato Tamotsu, Sudo Masato, Tomas Svab, Wang WuShang, and Kai Fusayoshi are on display. In addition, a hand-printed art volume of Einarsen’s work over the past few years is on display at The Terminal Kyoto, a rambling wooden house on Shinmachi Street near the SW corner of the traditional Gion Matsuri area. The exhibition, co-curated by Einarsen, also features works by Koo Bohnchang, Suzuka Yasu, Tomas Svab, Everett Brown and other fine artists, as well as Suzuka-san’s exquisite sencha tea service whose pottery, metalwork, textiles and glass are crafted entirely by local artisans.

Apart from it being an entrée to an intellectual and aesthetic feast, if you are a tourist, holding a KYOTOGRAPHIE passport will make you into a habitué. If you are already a habitué, it will allow you to become a tsu. However, as the festival has developed, and the numbers of visitors and the size of the shows have grown, KYOTOGRAPHIE has become less about its diversity of venues, and more about the photographs. That said, there is a palpable tension between the idea of images as images and images as the bearers of a message. For the past two years, KYOTOGRAPHIE has enjoyed generous support of one of its main sponsors, BMW (check out the Andy Warhol car at Nijo Castle). We look forward to future editions of KYOTOGRAPHIE.

KJ Associate Editor Susan Pavloska teaches courses in gender studies and youth culture at Doshisha University in Kyoto.

Images courtesy of Kyotographie