[M]asaya Kushino is a highly creative Kyoto-based designer who crafts exotic shoes which, rather than simply fashion accessories made to be worn, are more akin to dynamic sculptures.

He often utilizes highly-specialized traditional crafts techniques, employing master craftspeople to handle those aspects of fabrication, with striking results. He also fascinated by naturally-derived materials, assembling them in a riot of novel juxtapositions.

Having heard that Kushino Masaya had designed other-worldly shoes for Lady Gaga, I somehow imagined him as a reclusive old cobbler, someone I’d never come into contact with. On meeting him at a Kyoto Journal party at Impact HUB Kyoto in October 2013, I found him to be surprisingly warm, open — considerably younger than I had expected — and FUN. He made me laugh! I also learned that his shoes are essentially art works. Each pair is one of a kind. Sometimes he even makes only a single shoe… as a kind of whimsical invitation to the imagination.

So, when we eventually sat down for this interview, I wanted to ask whether he saw himself primarily as a designer, or an artist:

KM: For a designer, there’s a strong element of selling a product. The focus is on the client or consumer. For an artist, the main concern is expressing oneself. I think I balance both roles, depending on what I’m making or what kind of projects I get. My work is not just about the technical details of making a shoe, but an exploration of a fantasy, a story or something historical. For example, my “Reborn” shoes refer to a person aging and then being reborn. They can refer to one person’s lifespan or the history of people and rebirth through generations.

Who do you imagine wearing your shoes?

I don’t restrict my imagination by deciding who’s going to wear them or where they’re going to wear them. When you focus on these things the number of things you can’t do increases. But when you make the limitations zero, your imagination becomes unbounded.

What’s your personal essence?

Wow, that’s a hard question — it’s a difficult thing for me to understand by myself. I rely on others to reflect that to me.

Is that your answer?

I was waiting for you to tell me… [laughter]

So, how about the essence of your work?

Well, the materials I use are a unique characteristic of my art. Recently, I’ve been using traditional Kyoto materials, like Nishijin ori, (brocade) urushi (lacquer) and haku (gold foil). I’m also interested in sumi (charcoal). My style is to use these traditional Japanese materials and craftsmanship in a very non-Japanese, non-traditional way. My art is about relinquishing a specific time period or country and making it feel timeless and borderless. In this way I’m not preoccupied with the fashion industry’s trends or themes, which are seasonal and turn over very quickly. I need much more time to develop an idea.

Usually there’s a limit for fashion and shoes— a line that’s been drawn. I want to cross that line and go as far as I can. I want to push the boundaries, even with the finest details. I am especially attracted to ultra-fine craftsmanship, for example, cloisonné enamels.

How are you breaking rules in making shoes?

I’ve never studied how to make shoes. If I had, I may have fallen into a cliché style of making footwear. I studied clothing design at art and design university, but I never felt very passionate about it. There was a shoe competition — I had never designed shoes but I decided to enter anyway and I won! Since then I haven’t looked back. I am able to be more creative with shoe design because I don’t think practically like I did with clothing. Maybe that’s why there are so many male women’s shoe designers — they’re not afraid to make a 7-inch heel.

I design the shoes and finalize the work, but I rely on other craftspeople to help me realize my shoes. Many meisters prefer to undertake the entire craft process by themselves. I think that’s admirable, but there are also limitations to doing that. For example, I like to gather many artisans to employ their special expertise for different parts of one piece because I believe the overall quality is better. I also like to incorporate people and materials that aren’t usually associated with shoe making. But I’m not just trying to shock people. If I wanted to do that I would create incredibly tall shoes! It’s not about creating nonsense. My shoes need to be shocking and beautiful at the same time.

Who did you collaborate with for your lantern shoe?

I asked craftsmen who sculpt Buddha statues for temples, to participate. I didn’t want just any random woodworker; I wanted someone who would put their tamashii (soul) into making this. There had to be a strong spiritual element. They were the ones who actually sculpted the wood for the shoes, although I made the mold.

Where do you think your inspiration comes from?

I spent my childhood on an island off Hiroshima, called Inoshima. I’ve come to realize that what is appealing or beautiful to me, tends to be rooted in nature because I played in the sea and went on adventures to the forest every day. I would make a secret base and tie ropes together to make a swing. I collected shells, stones and crow feathers. Now I respect nature because it is something I can never control, and I take the forms of animals and use them as departure points for my art. If I had grown up in Tokyo, I guess my designs would be totally different.

I didn’t go to high school on the island, but instead went to a school that was two and a half hours away (one-way) by ferry. Although I loved the countryside, I thought if I stayed forever in a rural town, I’d never get out. My mother must have had the same fear — when I was young, before I fell asleep at night, she would point out countries on a globe and tell me about them. She told me repeatedly to go abroad. Once, after I visited relatives in Hollywood, California when I was in elementary school, my mum asked me how my trip went and my first response to her was, “Japan is small.”

When did you first realize you were creative?

My best grade in elementary school was always in crafts class —printmaking, carving wood, and making things with clay. Probably because I spent so much time with my grandfather, growing up. I was his first grandchild and we were always making things together. He taught me how to use tools. He was a mechanic who was really skilled with his hands and good at fixing cars. We built real boats, worked on my summer school project—a papier maché piggy bank — and a detailed wooden replica of a 5-story pagoda. He was like a mentor to me. Another person who influenced me was my great-grandfather, who made swords.

Is there a particular pair of shoes you remember from your childhood?

I don’t have a favorite shoe, but I remember one pair I hated. It’s nicknamed imogutsu (sweet potato shoe). It was white, with a thick rubber strap across the top. Everyone was wearing them. I hated it so much I never wore it. I thought, even back then, the design was so boring and cheesy.

How did you first encounter the world of fashion?

As a teenager I frequented a clothing shop in Fukuyama, Hiroshima, which sold the most cutting edge, leading fashion items. A charismatic fashionista there dressed phenomenally and taught me about fashion, particularly Paris Fashion Week. I would work in ramen shops or izakayas to make money because the clothes were expensive and he was a great salesman — I would spend so much money! It was important to me because I wanted to wear clothes that were unique and that no one else was wearing. I remember buying a white robot-like box jacket and trousers with lots of zippers on the side. I used to get strange looks from people on the streets. This experience inspired me to learn how to make clothes, so I could one day present my work on the catwalk.

I was also in a “visual band” around that time. A visual band prioritizes looks and combines make up, costume and music to bring out the unique sense of beauty of the band. I was the vocalist and would dress up like a Goth or dye my hair blonde and put in blue contact lenses to perform at live houses.

So why did you choose to live in Kyoto, instead of Tokyo?

Tokyo is said to be the center of fashion in Japan, but it doesn’t have a long history — everything is very new. It’s in constant flux. Things are born and die and the cycle is repeated very quickly. Things like Kawaii fashion can only happen in Tokyo. To produce great work, I thought I have to know about Japan and have a base here, and I felt where Japanese culture was most pure and present was in Kyoto. That’s how I came to Kyoto. I continue to live in Kyoto because it is a city of old and traditional techniques and this inspires me. Kyoto has many old temples and buildings with beautiful details. I feel inspired by how people have been practicing craft techniques for many centuries and how they respect the long history here. There’s a very strong sense of time in Kyoto — it moves slowly. The fact that this history has been preserved for so long means something special. I think it’s something that you can only find in Kyoto.

I saw an exhibition at MOMAK in Kyoto showcasing gifts given to the Japanese Emperor over the years. I loved the details and the luxurious materials, such as gold, pearls and special woods that were used to make these old artifacts. They are not for daily use and they are extremely special, unique and of the highest standard. I am really drawn to this quality and that’s what I intend to make with my work. I want to leave something behind that is special and worth remembering.

What did you learn by studying abroad?

While studying fashion design in Kyoto, I had the opportunity to go to Europe for a year to complete my course. Initially, to decide where I would live, I visited Milan, Brussels and Paris. First, I went to Milan. The food was great, and the city was beautiful so I left with a great impression. Brussels was interesting because there was a fashion festival week going on, but the city was dark. Finally, I went to Paris, where I was pick-pocketed, I got food poisoning and I was swindled. I also found that the city was really dirty. I came away with a terrible impression of Paris.

How did Milan change you?

Studying in Milan I learned how to make a collection, give a presentation and speak about my work. I saw how the West works — I saw good and bad parts. If the actual design itself isn’t great but the presentation is, then there’s still potential to be recognized for your design. I became aware of how Japanese people don’t really like to come forward and talk about themselves. Viewing Japan from the outside enabled me to see the strengths and weaknesses of Japanese design.

Who are your teachers?

My fascination with fashion began with Alexander MacQueen and John Galliano. I have learned from many artists and they all influence me and become my teachers. Miwa Kyusetsu and Yukio Nakagawa, as well. The first time I saw Nakagawa’s work I experienced culture shock. His work was beyond my imagination. What these artists all have in common is the originality, avant-garde and powerfully dramatic nature of their work. They made things no one had ever made before.

Ito Jakuchu was the inspiration for my most recent series, “Bird-Witched.” He is a Nihonga (traditional Japanese style painting) painter like no other. I love the roosters he painted. Highly detailed, almost deformed, not perfect, but all the more real and energetic. He seems to have been haunted by roosters, so he was able to paint them effortlessly. His style really resonates with me. He works in 2D and my shoes are 3D, so it’s like an evolution of the bird form.

Do current affairs influence your work?

As I’m not living in Fukushima it doesn’t directly impact me in the way that my home and livelihood is in jeopardy and I have to move. Fukushima isn’t part of my everyday reality, but I’m conscious of it. If I was always happy, I couldn’t create anything with great impact. But when I get angry, hopeless or stressed by watching the news, the negativity that I feel provides the power I need for my shoes and my shoes become the antithesis to those negative moments. I have two shoes in response to Fukushima: “Healing Fukushima” and “Reborn.”

Which are your three favorites, among your designs?

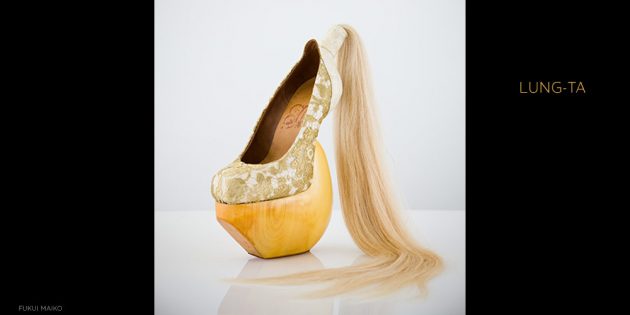

My “Lung-ta” shoe was inspired by a horse opera called Jingalo. I already had an image of what I wanted to make; a shoe with a ponytail, but I didn’t have a story. Lung-ta means “wind horse” in Tibetan. For the shoe, I used shiro nameshi (white leather) which is only produced in Himeji, Hyogo Prefecture and was used for yoroi (samurai armor). I felt that the wind horse is connected to the divine, so I asked a craftsman who makes butsudan altars to help with this process. The antique lace is from France. I love this shoe because it represents a borderless mix of cultures.

My ‘Reborn’ shoes tell a long and humorous story. It follows a kisyoutenketsu (a four-part narrative structure originally used in Chinese poetry). I used one shoe for the whole process. Initially, I wanted to grow flowers on the shoe, but that would have taken three years or so, so I compromised by changing out the flowers, like Japanese ikebana. I made it less than one year after Fukushima. The fire symbolizes human disaster, natural disaster or war.

I love birds. My “Chimera” shoe is simple but visually amazing. Don’t you think bird feathers are remarkable? Like with the peacock feather, the color, the details — why is it colored like this? It’s unimaginable and goes beyond human design. That is absolute beauty. Children, grandparents, anyone can love feathers. It’s universal. “Chimera” is a mix of a lot of different animals. Deer, sheep, sting-ray, and a fake cat’s paw. The human who wears the shoe completes the artwork and the life of the shoe. It’s a collaboration between human and nature, in uncharted territory.

Antlers, fur, bird feathers — they’re so beautiful and moving! They have forms which humankind cannot create, designed by individual species through evolution and adaption throughout their existence. It takes a long time for the form of an animal to develop and adapt into the most beautiful form. I’m borrowing power from nature and redesigning it, interpreting it through my own filter. That’s my role as an artist. The animal form is the most beautiful thing to me. It’s like a gift from the earth and I want to use that in my work, and if possible elevate it.

I love animals, so it’s a dilemma for me. I couldn’t use fur for a year because I saw a video on the Internet of a fox being killed for fur. I feel guilty using it, but it’s too beautiful not to use it. That’s why I want to honor its life and use it in a special way and make it even more beautiful, if possible. I want to make shoes that when you wear them there is no war but peace instead.

How are your shoes different from clothing fashion?

When you take clothes off they become formless. With shoes the form remains after you take them off. In that way they are like sculptures, and they connate something sexual. With a piece of art or sculpture you can only observe it but with shoes there is a bodily sensation — you can feel the shoe, and the material. When you wear a shoe you can become one with what you feel is beautiful! When you wear one of my shoes you can become your fantasy or your dream. You can become like an animal…

Celebrities wear your shoes. Is it hard to stay true to your values when this happens?

Lady Gaga’s staff wanted me to make heels in only one week for her to wear in NYC for a music video, but it’s not possible for me to make shoes so quickly because I work with a lot of people on each piece and it takes me time to develop an idea. I didn’t want to compromise the quality of my shoes, so I sent her a different pair that I had already made. My priority is my design style and the quality of the shoes.

What are you most proud of?

I’m proud that I have so many wonderful friends. I’m surrounded by so many good people, a community of artists. I’m so grateful.