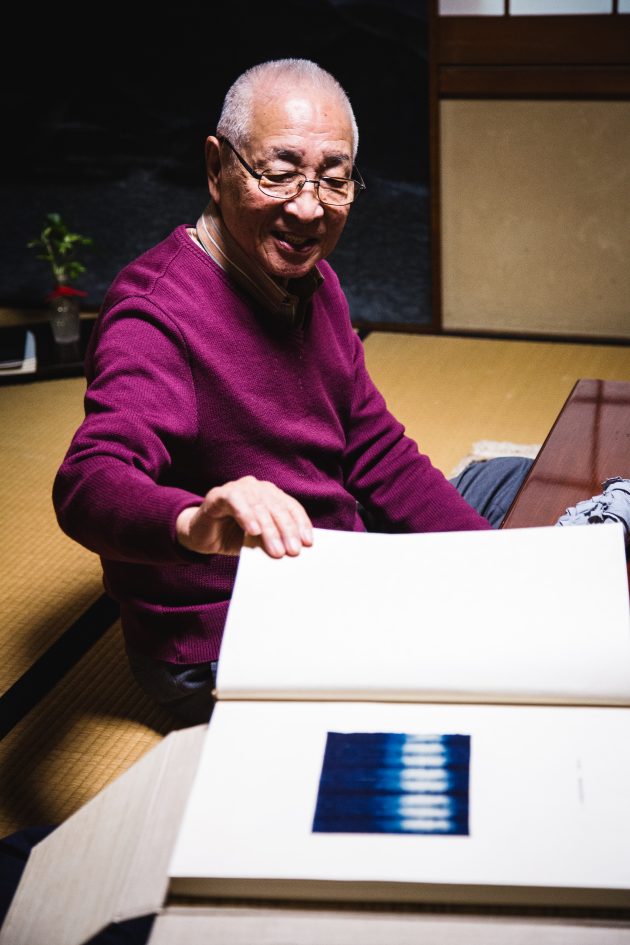

Nowadays, the Shigeno family name may be best known among the fashion savvy. Recent works such as Kazuo Shigeno’s collaboration with Japanese fashion powerhouse, Issey Miyake, in their 2019 KURA Exhibition “Resist Dyeing & Brushing Weave Pattern—Kyoto’s Craftsmanship,”* reveal that at 85 years of age, he is not a typical traditional craftsman. His second-eldest son, Yasumasa Shigeno, also interviewed here, has attracted attention for his revolutionary dyeing techniques applied to leather goods under his brand “Mao,” in collaboration with major department stores and high-end fashion brands. The family’s name and craft have moved beyond familiar traditional expectations and are reaching much more diverse audiences.

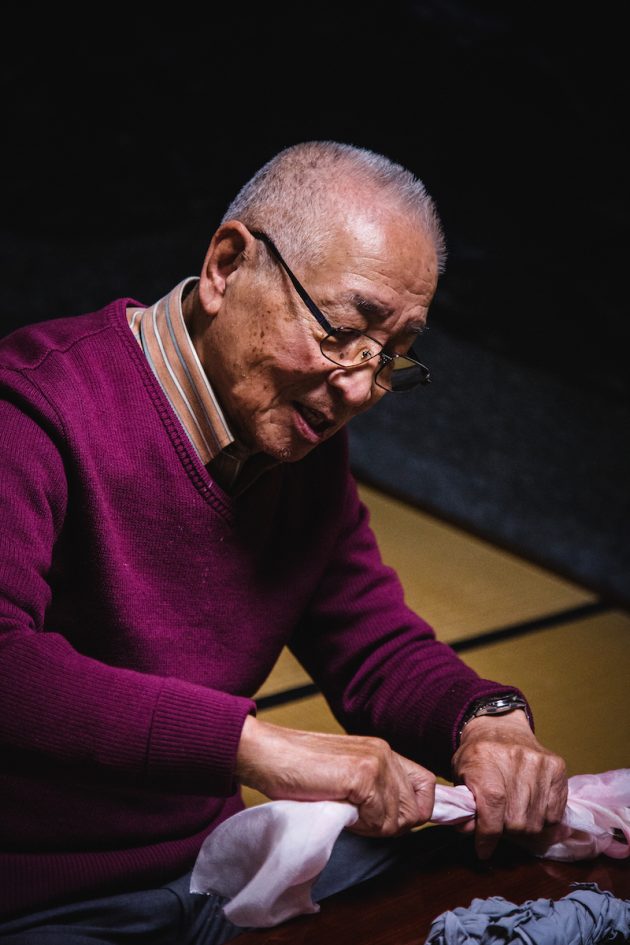

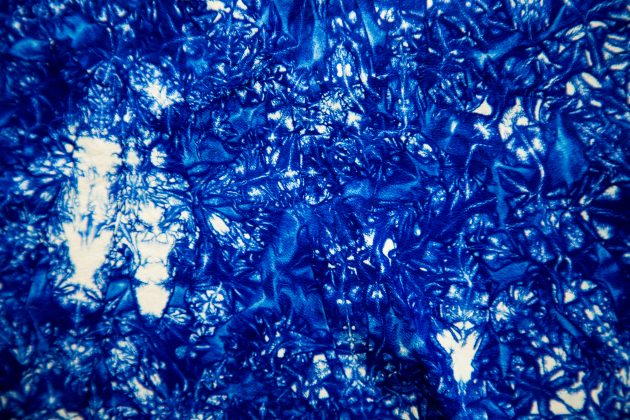

All certified as traditional craftsmen by METI (Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry), the Shigenos’ expertise is Kyo-kanoko shibori (Kyoto’s fawn tie-dye) —a technique named for its characteristic dyed patterns which resemble the white spots on a young deer. These exquisite patterns are made by initially binding the fabric with thread which prevents even one drop of dye from seeping through during the dyeing process. The thread is later released, to reveal contrasting colors of the dyed and non-dyed areas.

The roots of the Shigeno family business stem from Kazuo’s uncle, who stepped in as a father figure to raise Kazuo. What began as a small family operation in post-war Kyoto steadily grew into a limited liability company, during the time when shibori-dyeing was the face of the textile industry. As a designated maker, the family was constantly busy, working against the clock. It was not rare for the youngsters to slide late into their school classrooms, with dark circles under their eyes. In 1988, Kazuo launched his own company, S.D. fabric, with his eldest son, Fumihiko, as CEO. After having pursued a different path, Yasumasa also took his place in the family business and later became independent with his brand “Mao,” in 2011.

In earlier centuries, Kyoto’s textile industry thrived. Areas such as Kyotango and Nishijin became famous for magnificent textiles made possible only by the most delicate and intricate of weaving techniques. Incorporating the kanji radical 糸(ito/thread) in its name, “Ito-hen Sangyou,” the textile industry was formerly the heart of Kyoto’s wealth. However, along with the passing of the golden age of kimono, came the downfall of traditional crafts in the textile industry. With low demand exacerbated by the rigidity of a supply chain that ensured sky-high prices at market, weaving and dyeing families, out of love and fear for their sons and daughters, became reluctant to pass the baton to the following generation. Among Kyoto textile craftspeople, the current harsh reality is that around 20% “would like to pass on their craft but do not have a successor,” and around 40% “are uncertain about their business succession.” Out of these people, over 60% plan to close their businesses when they retire.

What does it take to maintain dignity in one’s craft, and persevere under ever-changing conditions? What has the Shigeno family perhaps done differently, to take off against the wind? The conversation on traditional craft and its continuance tends to emphasize “revolutionary”: new ideas, new people, new trends—overall, the future. Advancing into new fields—the Shigeno family is no exception. Yet perhaps, if we could rewind, look into the past and tune in to those who have experienced the ups and downs of the industry, we just may find those key ideas that have brought them this long way. Although their modesty hinders them from acknowledging it, the Shigenos seems to have upheld something we can all learn from. The following are some excerpts from a conversation with father and son—Kazuo and Yasumasa.

You are considered to be one of the pioneers amongst Japanese traditional craftsmen who have made their way into high fashion. Can you tell me how this all began?

Kazuo: Well, this was in our early days of S.D. fabric. The president of a Kyo-yuzen dyeing company came knocking on our door with a client, asking if we could dye a two-centimeter width, two-meter lace cotton tape. Coming from a kimono dyeing background—working from fixed shapes and sizes—dyeing something like that wasn’t ideal, and I could sense some weariness building up in the president sitting in front of me. But in our house, we have a mindset of never saying no—even the most bothersome orders must be greeted with a promising face. We stuck to this habit of mind, took on the job, did endless trials and errors with it, and got the job done to the client’s liking. We later discovered that this order came from one of the most prestigious high fashion brands in the world. Our relationship with this brand took off from there—constant orders during Paris Fashion Week and express orders for events, a personal thank-you note via fax after each success.

What was your motivation to start S.D. fabric?

Kazuo: We wanted to take things into our own hands. It’s usual for traditional crafts but the division of labor was, and still is, a big issue especially for Kyo-kanoko shibori. It takes seven steps for the whole process of creating the final products—undercoating, binding, bleaching, dyeing… During my uncle’s time, we only undertook the steaming process, pressing the shriveled fabric after the unbinding and adjusting it to the standard length and width of the kimono articles. But this division of labor was causing too much trouble: we were constantly blaming each other for mishaps. There was a lack of cooperation and the perspective that all steps would lead to one product. We began to consider the possibility of taking on the dyeing part as well. After my eldest son graduated from university, he became a trainee at the Kyoto Dyeing Laboratory, the main research institution for Kyoto’s dyeing industry. With him as CEO, we launched S.D. fabric.

Yasumasa san— it wasn’t until later that you joined the family business. You’ve also become independent. Can you tell me about the story behind this?

Yasumasa: As the second born, I just personally didn’t feel the necessity to follow my brother into the family business. I majored in interior design, then went off to spend my early twenties in Los Angeles, working in-store design. My brother encouraged me to come back and work with him in launching the dyeing sector of S.D. fabric, one year after its establishment. I worked there for twenty-one years and then created Mao. At that time S.D. fabric was operating at large scale, installing innovative machinery. I wanted to cater to smaller needs—to be able to work on something like a single-piece order using my own hands. I guess I kind of went backward, back to simplicity but in a different direction. My interest in dyeing various types of leather was also one of the reasons.

What have you learned from experiencing the decline of the textile industry in Kyoto?

Kazuo: Shibori was used to dye materials for all kinds of everyday goods. Now we’ve been fortunate enough to work for well-represented designers, but dyeing Western clothing was unthinkable. But this “unthinkable” is what we needed to make room for. As traditional craftsmen, we had a fixed notion of perfection, and being loyal to it was our job. Working with modern designers and answering to their requests that were completely out-of-the-box, we learned to make mistakes. These “mistakes” were taboos for us as craftsmen, but not for the designers. It was after these mistakes that an order of 100 became an order of 150. Being tolerant to the “unfamiliar,” was one thing I learned from them, yet I also believe I owe this to my uncle’s principle of simply “never saying no.”

Kyoto’s textile industry is struggling to survive. Do you have any advice for fellow craftspeople?

Kazuo: Kyoto is small. We seem to be doing well together, going out for dinner and drinks and so on. However, there is always a lone wolf—perhaps every one of us is a lone wolf. We need to change that. When I was 38, I was appointed as the youngest chairman of the union for Shibori craftsmen. Despite my uncle’s disapproval, I invited all the members to our home—shared my machinery, skills, every corner of the workplace was attended to and explained. Later on, a cooperative union for Kyo-kanoko shibori was established, bringing together the opposing sectors of the hierarchical system of “trade” and “craft.” Although it was not easy, we pulled away from our self-centered tactics and eventually leaned in for the sake of the common good.

It’s like I would tell my daughter, in the bathtub: when you try to hug the water towards you, the water will escape from beneath your arms, but if you gently give the water a push, it will come back to you. It’s all about the give and take. We’ve made progress over the years, but the division of labor still needs to be eased.

You both have experience launching and running your own business, is there anything you take away from each other?

Yasumasa: Growing up in a household where dedication to one’s work was the main focus, the notion of “thoroughness” was definitely handed down. This goes for polishing my craft, the long hours I dedicated to it, and the passion that goes into it. Because my father was thorough in his work, he was able to seek beyond his designated field and challenge himself to take on dyeing. I’ve watched my father for so long—honestly, it comes naturally to me that a job should be executed in a burst of effort.

Kazuo: I appreciate Yasumasa’s background. I’m glad he took those side paths when he did. His positive attitude towards incorporating foreign aesthetics has opened up opportunities we would have missed otherwise.

Do you have any advice for your son in running his business?

Kazuo: There’s a Japanese saying, “Daimyou hito wo kakaeru (a feudal lord holds many people).” Yasumasa needs to delegate. There is a limit to what one person can do. Speaking as a businessman, a craftsman, and also as a father, I’d like to see someone be my son’s arms and legs soon. We need to hand down what we have, to see businesses flourish, regardless of the field. We ourselves alone, do not amount to much.

What are some future aspirations for Mao?

I believe there needs to be a change of plans in where we find our audience. I’m moving towards European customers who can appreciate sustainable materials and methods, and am adapting to their standards. First, we need to overcome these hurdles in exportation, and then I can move on to showing what “proper” Japanese craft has to offer.

Any last comments?

Kazuo: “Certified traditional craftsman,”— sounds impressive, but honestly, it’s just a name. There’s no meaning in relying on it. As rice grows riper, the lower it bows its head. We mustn’t let ourselves be spoiled by sweet-talk.

*See also ‘Itajime’ in this video from Issey Miyake’s website:

https://www.isseymiyake.com/men/en/making/

Photos by Codi Hauka codihauka.com

Kyoko Yukioka is an interpreter and bilingual writer exploring her roots and identity in the ancient capital. Her recent focus in storytelling is to transmit stories across languages that faithfully reflect the thought and emotion in the words chosen by her interviewees.