“Alive, in each and every one of us, are countless individuals whose lifetime experiences, joys, sorrows, angers, doubts, and so forth have been successively passed down from one generation to the next. The physical form I assume now is but the fruit of what I’ve inherited from those who have existed before me. What, you might ask, has become of our ancestors’ ideas and emotions? Where do you suppose our creativity springs from? There’s no way that it springs forth from our finite and limited knowledge of life. I’m not the only one who has ever existed; our ancestors haven’t just died and vanished into oblivion. We’re not the fountainhead of our creative powers. Down through the ages our ancestors’ emotions and ideas have accrued and ingrained themselves in the imaginations of each successive generation.

That’s why whenever we start to unravel the threads of life’s tapestry, we ultimately reach the creation of heaven and earth. Each thread leads us deeper into the past. Don’t we dream? We certainly do so. Do our dreams explore only our finite experiences? And what about children, whose dreams do they dream? Our dreams not only unveil the world we’ve known from birth, but also the long period stretching back to the genesis of the earth. Our progenitors densely inhabit our souls.”

“In the noh theater, a player employs nonmovement and nonaction in his quest to create a rapport with the spectators. The ideal is to dance without moving. In fact, such sparseness of expression is an effective means to evoke the world of spirits, for inaction, more than physical movement, affects us on a much deeper level… Anyway, what’s the purpose of our being here? Ultimately, aren’t we here to link hearts? It’s a difficult challenge. Bear in mind that restraint plays an essential role in creating your onstage presence.”

“There’s an infinity of ways in which you can move from that spot over there to here. But do your movements allow us to feel your spirit? Have you figured those movements out in your head? Or are we seeing your soul in motion?…. the essential thing is that your movements, even when you’re standing still, embody your soul at all times.”

“We don’t get anywhere by remaining continuously on the move. At some stage along the way we need to stop and rest. Once we do so, a tiny hut unexpectedly appears from out of nowhere, a sanctuary in which we can refresh ourselves and take stock of our lives. There’s no need to continue without rest. What’s to stop us from just standing still by the side of the road for a while? …As human beings, we don’t grow while on the move, but during those dreams we inhabit as we stop and rest for a while. Isn’t it at such times that our souls evolve?”

Extracts from “Workshop Words,” Kazuo Ohno’s World, trans. John Barrett

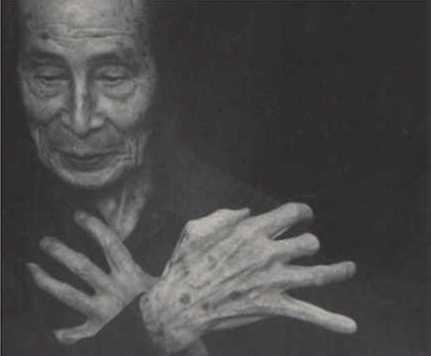

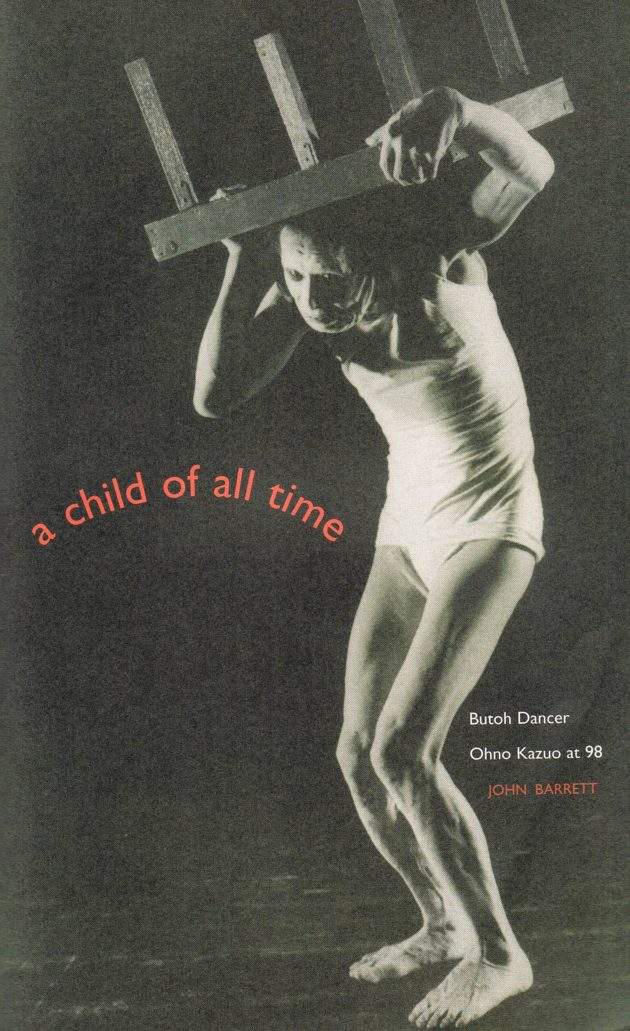

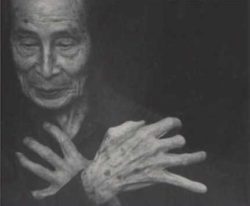

More philosopher than dance teacher, butoh artist Ohno Kazuo is one of the world’s most celebrated and celebratory performers. Despite his 98 years, Ohno continues to grace the stage, and with each successive appearance persists in pushing the human body to its limits.

Possessed of a rare, graceful, yet deceptively simple style of movement, Ohno relentlessly pursues personal truth and atonement, both in his onstage improvisations and in his talks to workshop participants. His performances are spontaneous, haunting, humorous, beautiful, and at times even spine-chilling. Although of late he has become frail and confined to a wheelchair, he nonetheless continues to perform in public.

Ohno has no need for a vast space to create a universe; he can do so by simply sitting stock-still. Nor does he seem to exist in a particular time and place; rather, time and place come to life by the sheer force of his presence. One might surmise that his ultimate wish is to die onstage, surrounded by those he loves so dearly: his mother and the spectre of his spiritual mentor, La Argentina, along with all those innumerable spirits inhabiting his body. Few dance artists have come to grips with human fear and bondage, frailty, love and failure as Ohno does. With every performance, he seeks to provoke an emotional volte-face in the way his audience responds to life and death, and to those around them. More often than not he succeeds. A central tenet to his impressive body of work is the idea that dance should force both dancer and spectator alike to question how they lead their lives, individually and collectively.

Ohno Kazuo was born on October 27, 1906 in the Japanese archipelago’s northernmost island, Hokkaido, the son of a commercial trawler man. He describes his father as being entrepreneurial, and his mother as endowed with a fine artistic sensibility though little time to develop her talents since her life was entirely devoted to raising ten children. A vivid sense of his early years and his attachment to his mother is to be found in the programme notes for My Mother. A physical education teacher by profession, Ohno first started taking contemporary dance lessons upon coming to Tokyo in the early 1930s. He was baptised in 1931, becoming a member of the Baptist faith. After being mobilised in 1938 he was to spend the following seven years on different warfronts, where, as a captain in charge of provisions, he came face to face with carnage and man’s innate savagery. In the wake of the Japanese surrender at the end of World War II, Ohno was interned by the Australian forces in New Guinea. On his return to Japan in 1946, he resumed his post as a gymnastics teacher at the Soshin Girls’ Baptist High School in Yokohama, and held that position until his retirement in 1980.

Parallel to his teaching career, Ohno periodically produced and created his own performances, continuing to do so right up to the present day. During the 1960s he was an active participant in the burgeoning Butoh movement, collaborating regularly with Hijikata Tatsumi, another beacon figure in the Japanese avant-garde scene. In the early 1960s he also started giving ‘open’ workshops in the rehearsal studio which he had built with his own hands in the garden at the rear of his home at Kamihoshikawa in the Yokohama suburbs.

Surprisingly, Ohno’s stage career only took flight in the late 1940s, at which point he was already in his early forties. His first-ever public solo recital in Tokyo in 1949 launched him on a performing career which continued unabated until the late 1960s. What followed was a ten-year hiatus, during which he underwent a profound transformation in his approach both to life and dance. Ever since the première of his comeback performance Admiring La Argentina in Tokyo in 1977 Ohno has persistently fused private history and dreamlike episodes in works of great subtlety, gaiety and pain. He was not, however, to gain universal recognition until 1980 upon presentation of Admiring La Argentina at the Nancy International Theatre Festival. This was the performance that alerted the world to the genius of Kazuo Ohno.

The first in a series of creations dedicated to those who played an influential role in his life, Admiring La Argentina, as the title suggests, is an homage to Antonia Mercé, better known as La Argentina, probably the most celebrated Spanish dancer of the 20th century, whom Ohno had the good fortune to see perform in Tokyo during her tour of the Far East in 1929. In the opening sequence of this watershed performance, Ohno symbolically departs this world only to return reincarnated as a young girl. While on one level, Admiring La Argentina could be considered a powerful portrait of his personal muse, it is also highly confessional in content, and signalled his spiritual regeneration after almost a decade of inactivity.

Nowhere, however, does Ohno more forcefully present his philosophy of life than in My Mother (1981), dedicated to his mother, Ohno Midori. In this piece he set out to undermine the conventional notion of dance as an aesthetic exercise in choreography. Set somewhere within an imaginary universe, this brilliantly atmospheric creation, replete with shades of nostalgia and melancholy, offers Ohno a platform on which to bare his soul, a soul haunted by multi-layered guilt. He brings his mother back to life as he frolics about with the small serving table placed as a prop in centre stage. Admittedly, it is nothing short of rash to try to patch together a performer’s life from their work, but when it comes to Ohno, one is obliged to make an exception. The themes for practically all his creations are drawn from the well of personal experience.

Underlying the deep sense of loss permeating My Mother, for example, is the fact that Ohno’s mother had to witness two of her children perish before they ever blossomed into adulthood. His younger sister was knocked down by a streetcar. Ohno’s baby brother died in his arms while the rest of the family looked on, helpless in the face of the tragedy that befell them. In another memorable performance, The Dead Sea, (1985) Ohno yet again mourns the loss of somebody close to him, namely, his father.

Within Ohno’s apparent craziness and theatrical flamboyance lies enormous humanity. Unlike many contemporary artists, Ohno scarcely concerns himself with the plight of the isolated individual. In his view, we are all born in and of this universe, and as such inexorably bound to one another. He fervently believes that the symbiotic bonds between human beings are invincible; Ohno is the artist of symbiosis. In stark contrast to many of his contemporaries, Ohno joyously shepherds members of the audience towards a rediscovery of their common humanity. He himself would be the first to admit that his ultimate concern is that the spectator should rise at the end of a performance feeling truly grateful to be alive.

It is no mystery why his stage appearances have enthralled so many round the world. He is unabashedly emotional, and while by no means mawkish, he does not sneer at our weaknesses. His approach is direct; his art subtle; no stranger to our everyday problems, he doesn’t try to conceal his frailties. If anything, he accentuates our human shortcomings. Ohno’s stage personae, such as his mother or La Argentina, are positive, life-affirming characters whose mission is to give and to share.

Perhaps to fully appreciate Ohno’s magisterial works, one should consider them in the broader context of his evolution as a human being. For everything is interconnected in his work. There is no boundary between the stage and everyday life. As one commentator put it in a nutshell, “Kazuo Ohno doesn’t commute.” Stepping onstage from the wings, Ohno invariably carries with him the shadow of his quotidian life; his joys and sorrows, fears and wonder permeate his every gesture. Nothing changes, and yet nothing remains as it was. His white make-up does not try to conceal his age-ridden face; his costumes do not camouflage his withering flesh.

While amiable and good-natured, Ohno is iron-willed. As many an interviewer has discovered, Ohno Kazuo is no easy assignment. He discusses readily certain aspects of his past and his cosmological views, but he has a tendency to turn every question on its head. Every answer leads back to his personal sense of attachment to the entire universe and his broader understanding of it. In one of his talks at the workshops, Ohno reflected aloud:“At some point or other haven’t we all pondered over the universe and its origins? The sky, the earth, the sun, the winds. What causes the winds to blow? Where’s that sun located? Over time, humans have given names to all these diverse phenomena. We even refer to ourselves as ‘people of the earth.’ The human species has a unique capability to immediately adapt to its environment. On reflection, however, it might be better that we call ourselves ‘children of the universe.’ Well, on second thoughts, you might argue that it’s inconceivable that such creatures could ever exist.

“Nowadays, I can’t get the universe off my mind. I’ve come to the conclusion that we’ll never be truly at home on earth until we experience becoming one with the universe. Domesticating ourselves isn’t what really matters. Above all else, we’ve got to realise that we belong to, and are part of, the entire universe. When and how, you might ask, did the universe begin? We merely confuse ourselves by trying to fathom the mystery of creation, and the origins of this world.”

Any review of an Ohno performance could stand by merely describing his charm and wonderful stage presence, and full of wonder it truly is. His sense of humour and childlike mischief are never far from the surface, and he takes impish delight in catching the audience off guard. Particularly impressive is the carnivalesque dance in The Dead Sea in which Ohno, in the guise of a Don Quixote-like figure, leaps out from the wings, flinging his cape jubilantly in the air as he charges towards the audience in total abandon.

Ohno is a dancer who explores the power of our emotional attachments, who through dance can justifiably, claim to have established a philosophy of life. He has constantly shown us what dance is capable of doing, and how it can make us feel. That, in itself, is a formidable achievement.

Ohno Kazuo passed away in 2010 aged 104.