by Solène Bouda

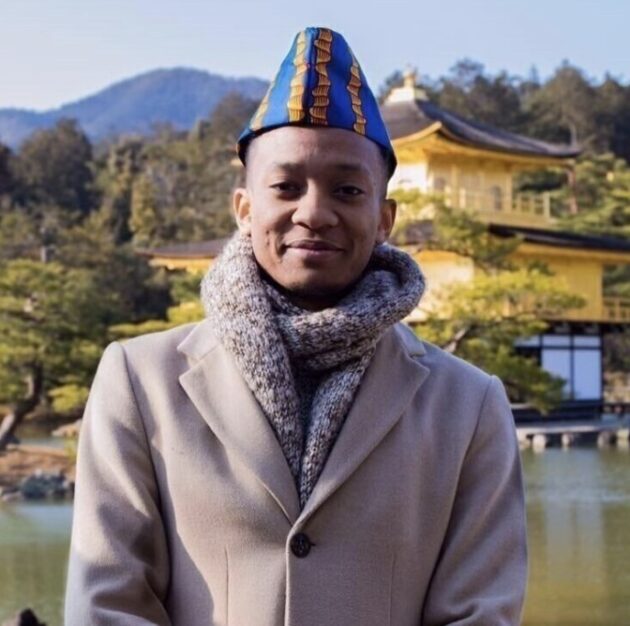

The African diaspora is one of the smallest but fastest-growing minority communities in Japan. Africans represent less than 1% of all foreign residents in Japan, yet within the last 30 years, their numbers have increased from a mere 1,000 in 1985 to 12,000 in 2014. “There are so few Blacks in Japan that when you see somebody, you see similarities, so you make it easier to be a connection and a meeting point for people,” says Sena Voncujovi, a Japanese Ghanaian entrepreneur and co-founder of Jaspora, an association created to connect the African diaspora in Japan and facilitate exchange between Japan and Africa. Sena was born in Japan, grew up in Ghana, studied in the US and China, and later returned to Japan. He is the son of a first-generation Ghanaian migrant who came to work in Japan in the 1980s, the early days of economic connections between Japan and Africa.

The first African community was formed in the 1980s by Ghanaians and Nigerians who were already working in Asia, primarily in China, and searching for new economic opportunities in an increasingly prosperous Japan. They were followed in the 1990s by other African immigrants through formal, economic, and educational channels, but most of the African residents in Japan today come from Nigeria, Ghana and Egypt. Many have secured long-term positions in the country, married, and started families. African migration continues in the 21st century as Japan is facing a workforce crisis, with an aging population and low birth rate compelling more flexible immigration policies.

Africans in Japan are part of a new wave of global migration driven by increased mobility and ease of communication. In that sense, they differ from the many diasporic African communities in Europe, the Americas, or the Middle East who have suffered historically from forced migration, slavery, and an inability to return to their homeland. Rather than emerging from a shared trauma, the African diaspora in Japan has developed as a community with a bond between their homeland and current home.

How do immigrants form an African identity in a country where Africans are so few? “I think when I came to Japan, where you are like the minority, you stand out so much… I realized, ‘Wow, this is it,’ [laughs] like, ‘this is me being African here, fighting for my rights’ [laughs],” says Hapra, a young Ugandan content creator. Being in Japan for over 10 years has shifted her perspective. Considering the few Africans in Japan, her identity as an African has taken precedence over her national identity, creating a sense of belonging to a broader community. “I think before Ugandan, I am African, you know?”

For some, being part of the African diaspora in Japan creates a sense of responsibility. “I think that Africans should put more value on themselves so that when they go abroad, they should be able to change this notion that people have about us… I have been an asset to this country from day one… because I totally worked hard towards it,” says Chike, a 33-year-old Igbo Nigerian urban professional based in Japan for more than 5 years. There is a sense of pride in being able to move across the world to work in Japan, a country renowned for high quality life and advanced technology.

Living abroad can be challenging and isolating, and many Africans have found ways to carve out spaces of belonging in Japan, ranging from informal meetings in the neighborhood—like for Hapra: “Yeah, I know Ugandans!!… Sometimes we meet on Fridays and have a drink or something”—to encounters in more formal places, such as churches. Chike says, “When I came to the church, they told me there was one Black guy who was coming from time to time… I was going one day to church, immediately he saw me and talked to me in Igbo language. There was this kind of connection. He was like ‘Wow, my brother, when I saw you, I knew it.’”

Many groups are working to build this shared community. Among them, Jaspora is a virtual and physical platform founded by two Japanese-Ghanaian brothers and one Senegalese student. They offer space for discussions around Africa and Africans in Japan, organizing networking events on themes like “The Evolution of Blackness in Japan.” Jaspora also took part in organizing the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in Tokyo. Sena explains: “Jaspora stands for Japan African diaspora, and I think that what makes us unique is that we are African-led… We wanted to create events and spaces that would allow Africans to network”. The brothers are active content creators on Instagram. Around 13,000 followers tune in to Sena’s reflections on African spirituality in Japan (@voncujovi), while his brother Pele makes videos about African experiences in Japan for 180,000 followers (@pelegroso_).

Online communities today play a major role in global immigrant communities. Platforms like YouTube and Instagram serve as both a lifeline to home and a platform for cultural exchange. They also allow Africans in Japan to share their experiences with an international audience. New technologies allow interviewees to stay connected with Africa on a regular basis, as Hapra describes: “I am really active on social media, yeah we keep in touch, we try every day.” Hapra runs a YouTube channel with over 4,500 subscribers and has collaborated with other African YouTubers she met through online informal networks. “Because we are in the same field, we follow each other on social media. So sometimes it would be like ‘Hey let’s do this video.’” Social media allows African YouTubers and subscribers to bond in a way previously impossible. “Sometimes [my African followers] comment on my videos, like ‘Oh thank you for representing us’, like ‘We don’t have many African sisters out there’ and I am like ‘Yeah thank you for supporting!’”

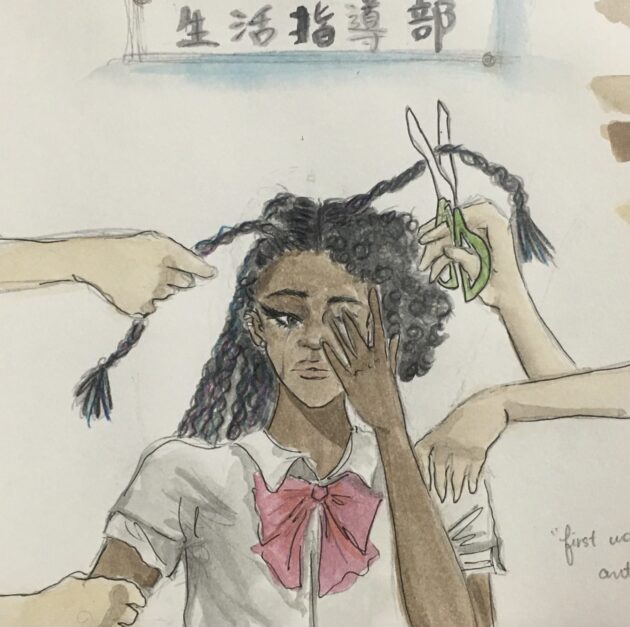

Japan can be a hard place to fit in, even for those born and raised in Japan by a Japanese parent. Mixed-race people, sometimes referred to as hafu, a Japanization of ‘half,’ report experiencing social marginalization, especially at school, and other forms of xenophobia throughout their lives. Ark Miura, a young Japanese woman with Ugandan origins, experienced racism and bullying as a student. “When I started Japanese school, sometimes I would be called ‘Bobby’ [a Nigerian TV personality in Japan] and my classmates would ask, ‘Can you speak this weird Japanese?’ or say things like, ‘Do you run fast?’”

Realizing one’s Otherness, one’s Blackness, is often related to traumatic early memories of not belonging. Ark says: “I feel like my earliest memories… you know when you start going outside, when I was with my mom, or ever since I was young, there would be, like, people staring at me.” For some mixed kids, being raised in Japan, where so few African people live, is to stand out in a negative way, through intense stares or bullying. “I think that from a very young age, I understood that I was different, that I was African black.” Challenges to assimilation are systemic, but experiences vary depending on the school or the social environment. Though for some having a multicultural background can be positive, the experience of standing-out is shared in common by all hafu.

For minorities, to be represented is to be heard. Now 22 years old, Ark is a Tokyo-based artist creating movies, songs, drawings, and short films based on her life and the experiences of people of African descent in Japan. She is the director of Keiko by Ark, an upcoming autobiographical documentary project recounting her life and drawing parallels with Keiko Clark, a Japanese woman born to an African American GI and a Japanese mother during the American occupation of Japan. Ark also founded the African Youth Meet-up (AYM)with members from the non-profit organization African Japan Forum in 2019. “For the majority of my life in Japan, I never fit in. So, the main goal is, like, young people with African descent… during AYM, they are allowed to be themselves… I think I would have gotten much more confident in myself, having these communities or representations when I was young.”

The presence of Africans and their mixed descendants in Japan provokes a redefinition of Japanese identity. Though Japanese African hafu are Japanese citizens, by being perceived as a distinct group, their presence calls into question the notion of Japanese homogeneity. Officially a binational citizen in Japan must choose one citizenship by the age of 20. Many hafu, however, whether African or from other continents, are able to use loopholes to keep two citizenships.

What is it like to grow up as a young African or hafu in 21st century Japan? In many cases, connections to Africa are not preserved due to geographical distance and a lack of time. Concerns about social exclusion also discourage many first-generation parents from passing on their African identity. Some parents deliberately distance themselves from their African identity in order to facilitate their children’s social integration. Still, for many people of African descent in Japan, this issue reflects a deeper, dual challenge: a sense of distance from both their African roots and Japanese society.

Other mixed couples take the opposite path, leaving Japan to live in Africa. The parents of Sena did just that. “We went back to Ghana because of the potential discrimination that we might face in Japan, as Black Japanese people. And my father strongly believed that we would grow up to be much more confident and positive about our Blackness and our African culture if we were raised in Ghana.” Hafu who grow up in Africa often have an attachment to Japan as adults, wanting “to know more about [their] Japanese roots”.

The experiences of African residents in Japan are diverse but they all reflect the fluidity of both African and Japanese identities. Despite their small number, the African diaspora and new generations of Japanese Africans challenge the narrative of Japan as a culturally and ethnically homogeneous nation. African community-building initiatives to promote multiculturalism are fostering an environment where African residents and their descendants can take pride in their heritage without facing social exclusion. Africans are creating a new home in the heart of Japan, where cultures intersect, sometimes clash, but ultimately evolve together.

SOLÈNE BOUDA is a French-Burkinabè graduate student of International Politics, who has lived in both Africa and Asia, and is currently based in France. In 2025, she interned at the Consulate of France/French Institute in Kyoto, where she deepened her interests in diplomacy, community, photography, cinema, literature, and much more. This article is adapted from her graduate thesis, advised by Dr. David Ambrosetti.

Learn more about Ark Miura’s documentary, Keiko by Ark, at https://www.coyotesunproductions.com/