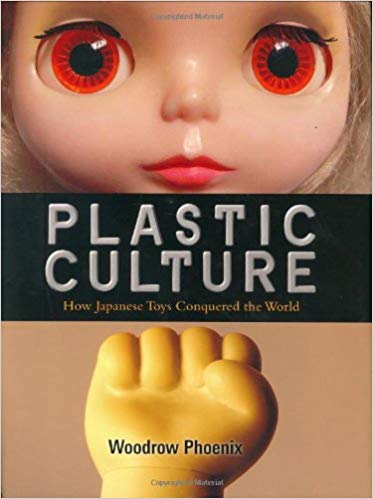

Plastic Culture: How Japanese Toys Conquered the World, Woodrow Phoenix, Kodansha International, 2006, 112 pp.

[I]F YOU VISIT JAPAN, you are likely to get the feeling the country is obsessed with characters and toys: children and adults play video games on trains, there seems to be a character mascot for every single product, and a Murakami Takashi toy/sculpture may be exhibiting at the local museum. Toys are everywhere.

[I]F YOU VISIT JAPAN, you are likely to get the feeling the country is obsessed with characters and toys: children and adults play video games on trains, there seems to be a character mascot for every single product, and a Murakami Takashi toy/sculpture may be exhibiting at the local museum. Toys are everywhere.

Designer/illustrator and critic Woodrow Phoenix, in Plastic Culture: How Japanese Toys Conquered the World, persuades us, however, this phenomenon is no longer unique to Japan. Defining a toy as “an abstraction distilled into concrete form,” Phoenix draws our attention to how toys have grown from being playthings for children to entering the mainstream, surrounding our lives, whether as art or furniture. He gives examples of famous companies and toys and tells their histories.

Beginning in postwar America, Phoenix describes how plastic was increasingly utilized, first to make generic toys (trains, dolls, tanks), then eventually, with plastic’s malleability, more detailed toys as with comic superheroes and television characters of the ’60s. Shirley Temple dolls, Batman and Buck Rogers figurines became increasingly popular.

In postwar Japan, Phoenix stresses the importance of toy-maker Kaiyodo, re-sponsible for making the plastic versions of such well-known characters as Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy), Dragonball and Godzilla, as a “key part of Japan’s otaku or “geek” culture.” Toy exports of companies like Kaiyodo to the West “have had an effect on the imaginations and markets of the West far in excess of their size.”

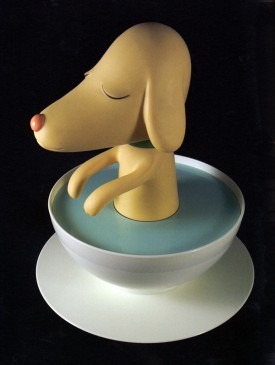

With the appearance of “urban vinyl” in the late ’90s, however, toys began to morph with design and art. Urban vinyl refers to “designer toys” or “boutique toys,” a movement of individual designers/toy-makers who make original characters for expression, rather than a mass marketing scheme. Influential designers include Junko Mizuno and Hong Kong artists Michael Lau and Eric So.

Well-illustrated and with short succinct essays, the book is an entertaining read. However, one is left with the feeling Phoenix is sharing his passion for toys with a friend rather than explicating the sociological mean-ing of toy culture. His cursory treatment of otaku culture, for example, a loaded term describing anime/manga geeks in Japan, does not do justice to how prominent and complex this subculture is.

Equally under-analyzed is his chapter on “The Toy as Art,” describing the Japanese Superflat movement led by Murakami Takashi and his Kaikai Kiki company. No doubt Murakami’s work, paintings/sculptures/toys of anime-like characters, derives from Japanese post-war consumer culture, yet Murakami has expressed in his Little Boy exhibition of 2005 his interest in exploring how Japanese culture was re-invented after WWII under U.S. occupation. His work is more complicated.

And the question remains, how and why have Japanese toys conquered the world? Stylistically, have Western toy designers been specifically influenced by Japanese designs? Japanese toys have indeed been exported to the West, but one can argue anime/manga characters and urban vinyl still cater to a minority. If the world was conquered, too few people seem to know about it.