The word “nō” (or “noh”) means skill or accomplishment; those who become ‘nōgakushi’ or professionals of the nō theatre are expected to have highly developed skills in utai (chant), kata (dance forms) and the musical interpretation of texts, as well as to be accomplished in all phases of production. When nō is performed, professionals from four different groups gather to combine their efforts to interpret a play:

Nō as a performance art is governed by a strict hierarchical system. At the top of the structure is the Iemoto, the head of the school, who is responsible for seeing that its form and style are upheld by all members. He acts as role model and is the main representative to the public. Shokubun and jun-shokubun are professional actors from other families who generally take their positions hereditarily. Each actor also has his own group of amateur and semi-professional students whom he trains. The semi-professionals are known as shihan or licensed instructors. Depending on the status of their teacher and their level of interest and competence, they may help backstage at performances by their teacher or the main troupe. They are responsible for assisting their own master in training his students and in organizing the activities of his amateur group. These amateur students are all called deshi or apprentices. In the position of uchi-deshi or shosei, young apprentices whose training to become professionals, in the past meant living with actors and serving as their assistants in all phases of daily life, but in more recent years means commuting from their own residences.

The apprentice is expected to follow his master’s words without question. After ten years he is expected to assist or represent his teacher, again without question, nor expect any monetary gain for a minimum of five years. After that, the apprentice may act more independently, forming his own group of amateur students, for example. But he is expected to remain completely devoted to his master all his life, as if he was a parent.

The master actor in turn allows the apprentice to observe and take part in his life more intimately than anyone else. It is the apprentices’ duty to take full advantage of this opportunity: to observe acutely and absorb all that is being transmitted on every level. The apprentice, with strict personal discipline, seeks to exercise his talents to the utmost; to succeed, he must be completely open with no desire other than to absorb humbly and correctly.

In 1960 Udaka Michishige was the last to be taken as an uchi-deshi, or live-in apprentice, into the home of Kongō Iwao II, the head of the Kongō School at that time. This was at a time when uchi-deshi often started their apprenticeship upon graduation from elementary school, as Michishige did, while this is no longer necessarily the case. The only son of a gifted amateur singer of nō chants who was also a scholar and professional painter, Michishige brought with him (and further developed during his ten years there) qualities of perseverance, perfectionism, and an eye for detail.

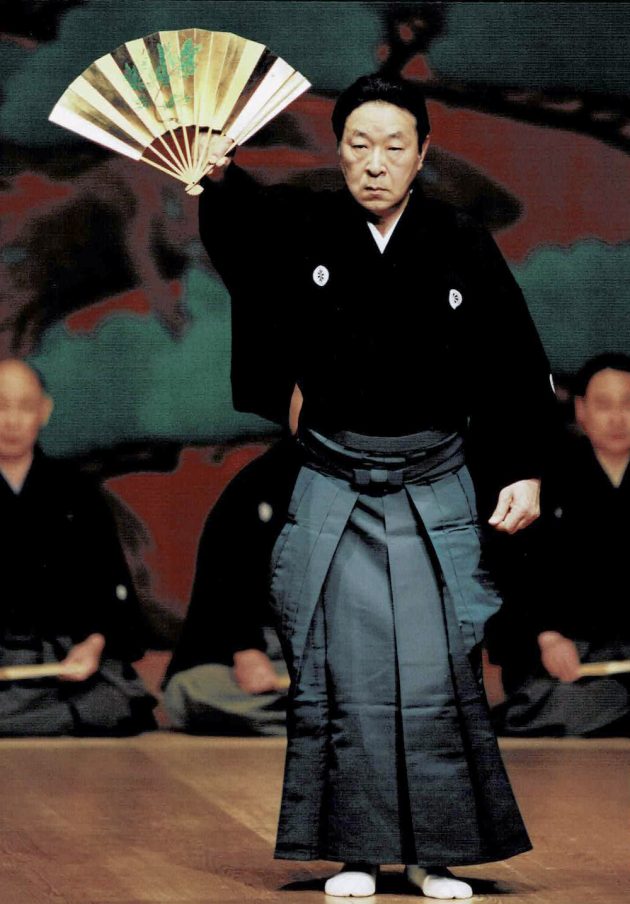

Michishige performed frequently throughout the year as a main or supporting actor, chorus leader and member and stage assistant, and vocal accompanist at recitals held by the hayashi-kata. He also led the Kei’un Kai, a group of Japanese students, and was the founder of the International Noh Institute, a group of foreign students of nō, who take part in annual summer intensive programs and in on-going training. Both groups include amateur, semi-professional, and professional students. He also carved masks for stage use and led the Udaka Michishige Mask Carving Group.

In 1989 he was working on a collection of reminiscences and observations of the world of nō which he hoped would make this complex, sometimes arcane form of theater, more accessible. The following are excerpts from that work.

MY FATHER’S UTAI

When I was a child, my father took me everywhere on his bicycle. Clinging to his broad back, I listened to the nō chants he always sang as we rode. Since it invariably was Shōjō, I soon knew it by heart.[1]

Now, in recalling those times, I see that my father not only loved nō chant, but also was quite a good singer. He had entirely committed to memory a number of pieces, and would often spontaneously sing them loudly, sometimes to my great embarrassment.

But as I rode along on my father’s bicycle, my ear pressed against his back, I could feel the mysterious way in which the sound of his voice vibrated along with the warmth of his skin. It was a living vibration, that arose from within his body; through it I felt both his identity as my father and, beyond that, his tenderness as a human being, the “spiritual vibration” each is endowed with at birth. To me, as a child, that vibration was indeed mysterious, and as I pressed my ear close, it seemed that somehow I heard my father’s voice coming from his stomach. “A-ha! You produce your voice with your stomach!” I thought. Not until thirty years later did I recognize that this was an acute intuition of the fundamental principle of voice production.

THE RIGORS OF TRAINING

Though at first I could not even put on my formal kimono or hakama by myself, by the time I was a second-year junior high school student, I had at last become accustomed to things. I had more opportunities for lessons and also to appear on stage. In June of that year I made my first appearance as a professional in the kuse dance section of Tamura.

Preparing for and performing the dance, Tsurukame, was a terrible experience. Though the day of the performance was approaching, I didn’t know what to do to study; I had learned that there was something called a katazuke, a book in which dance movements were written. Fortunately, there was a book entitled Shimai-katazuke in the Iemoto’s room. Luckily, it contained Tsurukame. I had asked the Iemoto many times for a lesson; but it was just three days before the performance that I finally arranged to be taught. From the start, the Iemoto, who had just had a bath, was in a bad mood. Without much confidence, I went through the movements I had been lucky enough to find and had learned vaguely. The book had said the dance started with a shikake-hiraki (a combination of movements involving stepping forward, pointing with a fan, stepping back while spreading the arms to return to the original position), so I began with these movements as I had been taught them. I was shocked to see the Iemoto, who before had only been in a bad mood, fly into a fiery rage and go abruptly upstairs.

The faint hum of a fluorescent light sounded hollowly on the jet-black stage where I continued to stand, a solitary figure holding an open fan.

The katazuke had been wrong.

Two days later I was able to have another lesson, but on the day of the performance I was under quite a strain on stage. I finished the dance but made a mistake at some point; just as I went through the kirido the Iemoto slapped my left cheek.

For the first time I realized that a professional’s training meant intently watching the Iemoto first of all, then the other professionals on stage, and listening with careful attention to the utai and the musicians. After that incident I got a buzz cut and resolved to be strictly disciplined while in training.

I made it a special point to spend more time on the stage. Day after day, after wiping the stage clean with a damp cloth I polished it with a cloth bag filled with roasted rice bran. The time I spent polishing the stage was the only time I could call my own.

Whether day or night, the Iemoto would call for me, and without uttering a word, tap his shoulder meaning, “Massage my shoulders!” After I had massaged his shoulders, he would then tap his legs and I would then massage his legs. Fortunately, or unfortunately, I was good at massaging shoulders and legs. Even if I had a cold and a fever, even before tests at school, or late at night, I would be called on to massage his shoulders and legs. Another of my duties was to help prepare the costumes before each performance and iron and put them away afterwards.

Before I knew it, I was preparing to start my fifth year at the home of the Iemoto.

At this point the Iemoto had been in bad health for some time and tended to keep to his room. Once I secretly caught a glimpse of him in his suffering. When I think about it now, I believe that his suffering was inevitable.

The previous Iemoto, who had been both his father and teacher, had passed away at an early age. When I became a live-in apprentice the Iemoto was, at thirty-six, head of the Kongō School and thus the main representative of one of the five schools of nō. As such, he was expected, as a matter of course, to possess the pride of an Iemoto, and power as a nō actor that could compare well with actors of other schools. But because the previous Iemoto had died early, he had not received adequate training in nō. Even though he had been born with what seemed to be the perfect instrument: inborn genius, a natural elegance, the physical characteristics to best express the beauty of nō — he had lost his living example of the art. Thus, performance by performance, he was continuing in self-instruction, pursuing his studies through times of mental and spiritual torment, worry, disappointment, dejection, and loss of self-confidence. Through this excessive pressure and pain he was finally destroying himself.

This sickness of the soul could not be understood by others. Though there were people around him, none who could support him through this. The extent of the Iemoto’s suffering was limitless, his sadness deep as the ocean. For me it was like seeing hell itself. The Iemoto’s trials followed one after the other with each performance.

At sixteen this was the first time I had seen “the hardships of life,” and how a person could continue to walk on one path in pain, to the point of madness.

EFFORT, DESTINY AND GUARDIAN DEITIES

In the fourth year after receiving independence from the Iemoto I debuted in the virtuoso play Shakkyō, followed by debut performances of Shōjō-midare and Mochizuki.[2] Five years after that I produced my debut performance of the virtuoso piece Dōjō-ji.

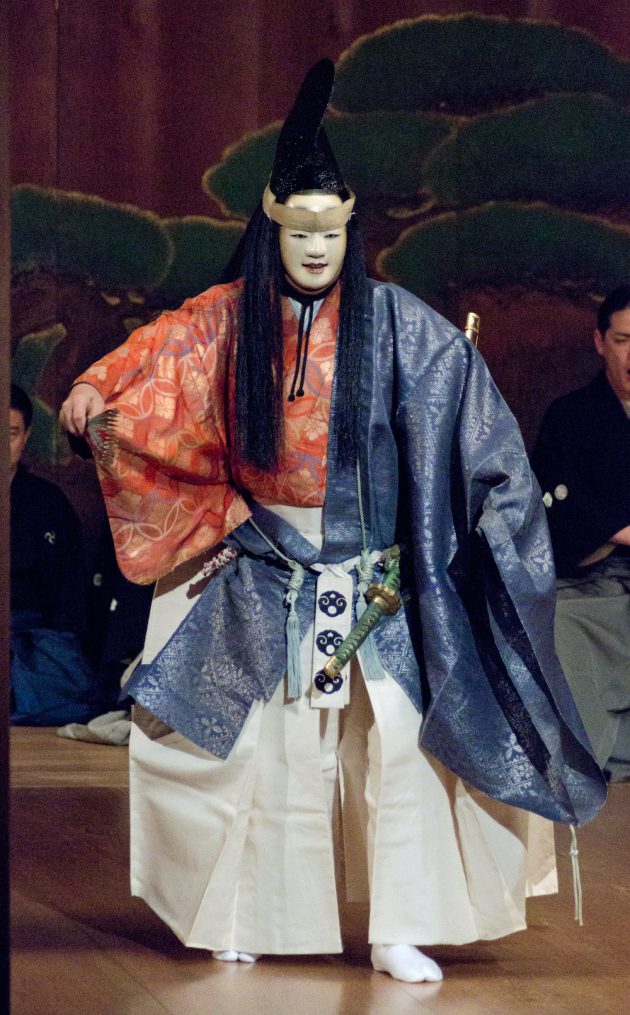

The thought of performing Dōjō-ji was like a dream within a dream, a thing far, far beyond my reach. Of the two hundred-plus nō plays in the present repertory, Dōjō-ji is the most difficult of the difficult, virtuoso, pieces. The actor risks his life in the instant when he leaps up into the heavy bell as it falls. It is such a difficult piece that it is said that the actor who completes Dōjō-ji safely has become a true nō master.

But the truth of the situation was that I had to perform Dōjō-ji. Thirteen years after becoming independent, my nō performances numbered about forty, and to properly be considered a member of the elite among nō masters, I was deeply involved in training for serious nō. And as I prepared for Dōjō-ji I felt I would be crushed by an unsparingly ponderous agony and tension that could not compare with my previous nō experiences.

That year I was thirty-six years old, by coincidence the same age the Iemoto had been when, as a first-year junior high school student, I had become a live-in apprentice.

I now knew that the suffering I was undergoing was that which the Iemoto had felt, the suffering for nō I had glimpsed during those years as an uchi-deshi. For the first time I realized the greatness of the Iemoto’s stature; I thought how strange it was that I should be living now in the same world as he had been living in then; at the same time it gave me a curious feeling of reassurance.

In addition, the fact that I had safely and thoroughly completed my time as an apprentice with the Iemoto was a fact of such historical importance that no words could express it. I understood now that no one could change that fact or deny its merit. At the same time, I had the premonition that in the future as I prepared for nō performances I was destined to experience many times over the suffering I had gone through as a live-in apprentice.

At times in fact, I thought my life as a live-in apprentice had been far more comfortable, and I longed to return to those days. This was how difficult my present reality was. In a way my training as a live-in apprentice had been a struggle between myself and the Iemoto. Now, after my independence, my battles were with myself alone.

Wanting to acquire my best possible physical condition and spiritual energy, I spent much time in training, running at a neighborhood playing field at night.

Not many people passed the spacious playing field after nightfall, when the field became very very dark, the light from the streetlamps barely penetrating the tall poplar trees that surrounded the area.

One night, after I had run the usual three or four laps and had stopped in the southeast corner to catch my breath, I suddenly seemed to feel something warm in the sky; I looked up and I saw a truly strange object flying slowly over, without any sound.

It was completely flat, light brown in color, and well over twenty tatami mats in size; for some reason, I instantly thought that it must be a bird. The object was moving slowly from the northwest to the southeast; city lights shone faintly on its edges, which resembled a bird’s wings. For about fifteen seconds I stared, until the trees obscured it as it disappeared into the darkness to the southeast.

I remember thinking that there were living creatures on earth that we know nothing about; and no matter how I pondered it, I didn’t know what this was.

Certainly, from the time I could think for myself I have believed that there are inexplicable natural phenomena.

At times they appear in a particular shape, at other times they ride the wind and are not like words or signs, but more like telepathy. On many occasions they have addressed me. But at that time I was too immature, both in age and knowledge, to understand the messages.

During one especially difficult period, when I had been experiencing disappointments in nō training, performances, and in my personal life, for almost a full week I was not able to sleep, no matter how much I drank and otherwise abused my body. When at last I succeeded in getting some sleep, even though for only three hours, what a blessing it was!

Then one night, not long after, when even in my dreams I was at the lowest level of my suffering, creatures such as I had never seen before, two great snakes, completely black with a pattern in white on their heads, glided into my awareness. These two snakes coming quickly to me, slid under my legs. Raising their arching necks they took me upon their heads, and before I knew what was happening, were taking me away. When we arrived in front of a certain house the two great snakes slithered off to the right and left and disappeared.

That was a turning point in my life. After that dream my fortune turned for the better.

Three or four years later, when my memory of this strange experience was getting hazy, these two great snakes appeared to me again in a dream. Moreover, in this dream they appeared to me clearly on the nō stage.

In this second dream the weather was very fine, and I was just about to go through the kirido (the low door on the side of the stage used by chorus members, and actors in some cases, for their entrances and exits) to practice. According to a person standing on the hashigakari in my dream, whether it would be quicker to say: “With this fine weather it is a Day of Double Beams of Happiness and you are being watched over this day,” or to signal: “Look there!” the two great snakes that had appeared to me before in my earlier dream were coiling and twisting together across the stage

Upon awaking soon after, I thought over the syllables I had heard, “Sō-Kō-Shō-Jitsu,” and strangely enough the characters for the phrase: ‘Pair, Light Rays, Good Omen, Day’ formed effortlessly in my mind.

For a long time I did not understand the meaning of this portent. It was six years later that I learned that these two great snakes were dragon gods and had been watching over me since my birth.

Dragon gods, as the guardian deities of Buddhism, are part of the assembly of the Buddha. Deep within the earth, or in the lower depths of bodies of water, they wait in stillness a thousand years, three thousand years, for their time to act. It is said that once that time has come, what has been set in motion will not be stopped. Even now the words that were impressed on my mind remain a mystery. But I am sure the day will come when I will understand what happened in this dream.

A WARNING

In 1984 I attended a symposium to discuss Kyoto as representative of Japanese culture. Other members of the group included famous scholars and business leaders.

While Japanese culture was the theme of the symposium, the discussion centered on new architectural styles or techniques to be used by the vanguard of industry in the future, or education in Japan and how it would be supported by high technology. If anything, it seemed to me as though everyone was absorbed in playing at debating controversial issues of technology. While the discussion was to have included Kyoto’s 2,000 years of culture, not once was the topic of nō, recognized the world over, not only as being pivotal in the traditional performing arts, but also as part of an aesthetic literary tradition, brought up. It seemed that to those in the position to lead Japan into the future, nō was a part of their heritage already shut away and forgotten, as though in a museum.

While to some nō seems at least on the surface to be maintaining 600 years of tradition and to be passing on this tradition to successors through training, it should be pointed out that in actuality nō owes its present existence to a limited number of devotees. It is the general nō enthusiast who, by buying admission tickets, supports the actors’ livelihood and performance costs. In turn this creates support for the traditionally structured world of nō: the Iemoto, or heads, of the five schools of shite (main actor), and the Iemoto of the sanyaku (waki, kyogen, and musicians) stand at the pinnacle of a feudalistic pyramid, with absolute power. Each school maintains its own particular style, and plans for expansion. Within this vertical society the professional nō actor is kept in his place at the base.

It would be no exaggeration to say that 90% of these fans are deshi (students or apprentices) of the various actors. In other words, nō exists at present because of these students. And certainly if the number of students increases, nō would flourish according to plan.

But if we ask the professional nō actors what nō is, why they perform, or if they understand the essence of nō, we find problems. Rather than consider such questions, their thoughts focus on what to them are the more important activities, i.e., continuing traditions and maintaining their particular schools. For that reason, nō today exists only to protect the actors’ livelihood, not to represent the real essence of nō.

According to my studies, the roots of nō are to be found in a variety of literary sources, the Kadensho of Zeami and Komparu Zenchiku’s treatises on the life and art of the nō performer being of primary importance. Also, I have searched for the roots through my own experience in performing nō, in the literature of the texts of the plays themselves, in the forms of nō movement, and in the carving of the nō masks, of central importance to the actor. I have found spiritual sources for nō, too, in accounts stating that nō began with the Buddha, or was passed down from the Age of the Gods.

Through nō, the land is protected, the Buddha praised, and evil spirits subdued. There is nothing that could be more profound and sacred, more elegant and simple. Beyond this, there is evidence, too, that the movements of nō were derived from the mudras formed by Kannon, and the chant from the words of the Buddha. The primary inspiration of nō then, so linked with a spiritual past, must be redemption and salvation for all living beings.

Zeami’s son-in-law, Komparu Zenchiku, believed that nō was an art with the power to relieve suffering. He thought of nō as equal to religion on a spiritual level, and even felt that it should be left to the world in the form of a religion.

Nō is the ultimate dance form, in which heart, body, and words become as one. It could be called an art form of enlightenment, with the deep contemplation or meditation, found there as yugen (subtle profound beauty) or hana (flower, a transcendent moment), something like enlightenment or perfection in the present existence.

While Buddhism, as practiced today, slips into a materialistic decline, though nō has spiritual and religious qualities it exists in a different space, separate from religion. This is because it is an art which rises above religion. However, for it to be an art form which truly moves the viewer, the mountain of its spiritual qualities must first be scaled and conquered. Then for the first time, on a higher plane, true yugen will be revealed and true hana will appear.

I have been thinking for quite a while that there are great errors in nō today. Something is wrong — something has gone awry. I believe the essence of nō is being transmitted incorrectly, and its spiritual qualities are lost in present-day nō. To try to portray the various roles of nō — gods, demons, madmen, the spirits of the dead suffering in agony, the paths to salvation from the illusions of life — without any spiritual preparation, but superficially, simply imitating outer forms, is a grave error indeed.

Sadly, Udaka Michishige passed away in March 2020. This article was originally published Summer 1989 and revised May 2020.

The International Noh Institute

[1] A popular short play, often one of the first learned by a student of noh chant, Shōjō tells the story of a youth in China who is rewarded for his filial devotion with an inexhaustible jar of sake by a shōjō, a sake-loving water sprite from the sea.

[2] Shakkyõ, Shōjō-midare, Mochizuki, and Dōjō-ji are considered hirakimono, virtuoso plays requiring the direct transmission of unique features when being performed for the first time. Especially for a young actor, they are considered vital indications of growth and proficiency.

See also: Udaka sensei’s piece on Noh masks in issue KJ90; and Step Inside the World of Noh with Diego Pellecchia

Udaka Michishige, professional Noh actor and mask carver, taught and performed in Japan and abroad, and also authored Noh plays. In 1991 he was designated a representative of a National Intangible Cultural Asset. In 2019 he was the 29th recipient of Hōsei University’s Saika Award for lifetime contributions to noh.

Rebecca Teele Ogamo, Senior Director of the International Noh Institute, started training in Noh and mask carving with Udaka Michishige in 1972. She received her certification as a licensed instructor of the Kongō school in 1980 and became the first non-Japanese member of the Noh Performers’ Association in 1996.

Photography by Massimo Fioravanti. Contact: fabiomassimofioravanti@gmail.com