Many artisans of traditional Japanese crafts are facing a growing problem: difficulty attracting apprentices to carry on the work in addition to decreasing sales as younger populations eschew traditional items for cheaper, trendier alternatives. However, in Tokyo’s Shitamachi neighborhood, a high concentration of artisans persevere.

This culture, rooted in the tradition of hand-crafted items, may seem mismatched to the high-tech, fast-paced futurism of Tokyo. But the history of Shitamachi’s artisans is emblematic of a distinct Tokyo-style aesthetic, largely an Edo-period development, that established iki, a cool elegance which remains deeply infused in artisan sensibilities and in modern Tokyo fashion, architecture, and design. Some Shitamachi artisans are working to marry their historic relevance with contemporary interests, attracting younger generations to take up traditional tools or incorporate these creations into their modern lives. The following artisans are examples of those who are connecting with younger creators and customers, transmitting the value of craft culture to the next generation.

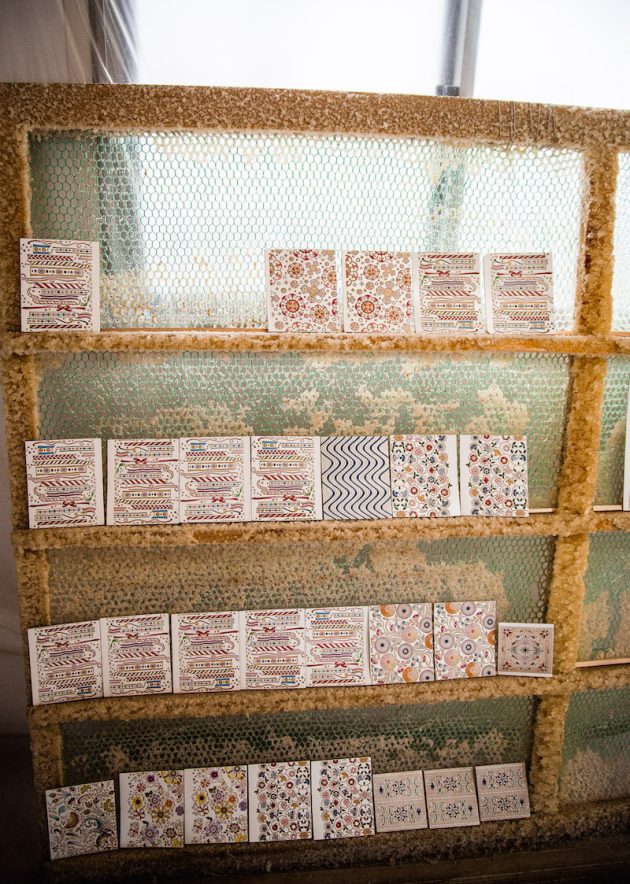

bunkogawa leather

Handmade embossed leathercraft makers, producing wallets, coin purses, book covers, and other small items using methods that have been passed down for three generations. Many of Bunkogawa’s artists are young creators whose colorful, sleek designs attract an array of customers.

“I believe it is important to be constantly evolving, and to think about how to evolve.

While bearing in mind that the present exists because of the past 92 years, we inherit the good elements of the past and change what does not fit with the present. Without adjusting to the changing environment, we would just be following the path to extinction.

I believe that tradition is something that is built upon the results of successful change and adjustment.

We are dedicated to creating products that can be enjoyed by both younger and older generations. There is no distinction that considers one type of product for certain customers because they are younger, and another type of product for other customers because they are older. It’s really a global design.

We do get applications from young people, but also from people in their late twenties, people starting their second career in their 30s, or even housewives whose children do not require so much work anymore. There are many people who are interested in working as an artisan. Rather, I think the successor problem can be solved by creating a proper supporting environment that is compatible with today’s society for those people.

I believe the future is extremely bright, as long as we keep reacting to the times’ changes. If you let yourself be crushed by the word ‘tradition’ and fear change, the future will be dark.

I am certain that the right way is to be constantly implementing change as an answer to the customers’ needs.”

Website (Japanese): https://www.bunkoya.com/

kazari kanzashi

Takashi Miura is a fourth-generation kanzashi artisan—intricately handmade hair ornaments that are traditionally worn with kimono. His workshop includes a small museum detailing the history of kanzashi, alongside a small collection he has curated to display their various styles.

“Kanzashi are based on motifs such as animals and plants in nature. Because my craft is about representing living creatures using metal, I make a habit of consciously observing nature. By being in touch with the 5 senses—vision, hearing, smell, feeling and taste, I try to encapsulate the feel of nature in my work.

Due to the lack of potential successors and a decrease in demand, we are practically an endangered species. Because of that, I started to actively create kanzashi that are not only for Japanese hairdos but can also be used by a more universal clientele.

I employ social media to spread information about our products, the craftmanship that goes into the product, as well as demonstration events. Additionally, we provide kanzashi-making experiences at the workshop in order to attract attention to the craft.

With being an artisan comes the struggle of creating, but the happiness after completing a product fuels the step towards the next creation. Hearing the delighted feedback from customers is also a source of energy.

In the future, I wish for the young people not to retreat into a box, but to jump out into nature to cultivate a rich and creative heart.”

Website (Japanese): https://kazashi.exblog.jp/

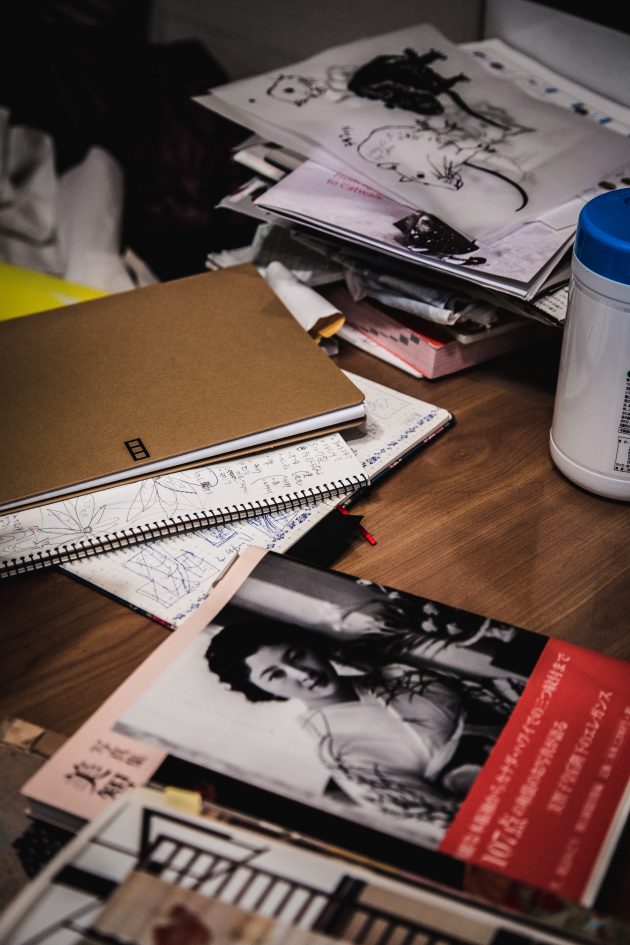

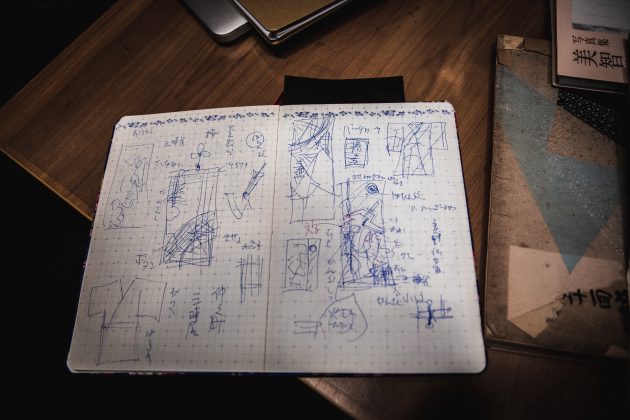

rumix design studio

After obtaining fashion degrees and formal training in traditional kimono design, Shibasaki Rumi combined her professional experience and personal artistic aesthetics to start her contemporary yukata brand “Rumi Rock” by Rumix Design Studio in 2005. She and her team create distinctly modern, edgy patterns and designs that draw from a wide range of artistic inspiration, such as motifs from works by author Yukio Mishima and the Daigo Fukuryū Maru (No. 5 Lucky Dragon, a Japanese tuna fishing boat that was contaminated by nuclear fallout from an American weapon test).

“Regarding graphical concerns, I try to keep everything in mind that catches my eye.

Aside from that, potential themes for my designs are always on my mind. News, history books and literature are where I get most ideas. I take note of anything that feels close to my heart.

Looking forward, our lives need to be the opposite of mass production: a small and honorable living.

It is possible that for new artisans who used to be part of an ordinary company, this is a field that offers optimistic prospect. If the people do not craft a future for themselves, they will be easily disposed of. Reading and writing, soroban (Japanese ‘abacus’), hand-sewing, carpentry, cooking and farming—I would love for kimono to be a symbol of beauty that all these activities have in common. I believe that dyeing patterns onto textiles and bringing those out is essential for small countries and communities.”

Website: https://www.rumirock.com/

his factory

Katsuhiko Nakano creates one-of-a-kind, made-to-order leather bags. Nakano uses colorful fabrics and unique details for his bespoke goods, differentiating his work from that of traditional leathermakers in the neighborhood. He has been able to attract younger people to his handcraft through workshops and providing bespoke, high quality goods that stand out from fast fashion goods.

“I am the only one doing this. I have been working with leather and making bags in this field as a craftsman for 30 years, but I view my style differently from [traditional] kinds of artisans. Simply put it is a new style—if you want to call it that.

There are certainly challenges in producing custom made. Making just one single bag, from the zipper down to the last metal fitting, is very difficult. You might say it would be easier if we just kept the parts stocked, but the materials that are needed vary with every order. Usually, a craftsman will not—or rather cannot—do custom made for this reason.

Surprisingly, however, once I started down [this] path and made it work anyway, I had many customers who were bored by the bags they saw in the department stores. They are not interesting, they said. The customers aren’t able to find what they want anymore.

So, the times are changing and the number of customers who do not prefer cheaper mass-produced products is increasing.

My history is still very young, and these traditional artisans are much greater in that sense. I suppose I found out that I liked meeting and talking directly to the customer. Before, I didn’t see the world beyond ’this part‘ [of the business]. So inevitably, I had to butter up big companies in order to get orders. But now, I talk to the customers directly and it is a much more enjoyable experience for me as well as the customer. It’s a win-win situation.”

Website: https://his-factory.com/

wanariya

Aizome is a longstanding traditional dyeing technique that uses fermented indigo leaves to create the preeminent blue shades that distinguish Japanese indigo. Wanariya uses aizome technique for casual wear and runs workshops out of its studio in Asakusa. They aim to make the tradition and culture around indigo dyeing more accessible via their welcoming space and wearable products.

“One reason why aizome has survived until this day—by being utilized for kimonos and t-shirts alike—might be the fact that it is not simply beautiful, but practical as well.

Our concept is to create a space that is easy to enter, which disproves the commonly perceived high standard of tradition. I believe that traditional culture such as this will be able to persist in the future because of the people who connect and familiarize themselves with the craft.

With the Olympics drawing nearer, traditional culture is getting an increasing amount of attention. I have heard from many people that the idea of traditional crafts being rigid and unapproachable is still common. However, the reality of it surviving all these years just proves that a significant number of people have been practicing the craft. I believe the craft is not something special, in fact it has persisted to this day as a tradition precisely because it has been a common part of everyday life. We want people to understand that this used to be something any townsman could practice, so it is not difficult.

The most important thing is bringing the craft and traditional culture closer to the people. The more people we reach like this, the likelier the survival of the craft as a part of Japanese culture.”

Website: https://wanariya.jp/index_mobile_english.html

***

All of these artisans appear in the book Takumi: Downtown Artisan Culture (Kingyo Ltd. Hong Kong, 2019) by Manami Okazaki, who has extensively covered the worlds of Japanese art, crafts and fashion through her writing. We thank her for generously connecting us with the people who contributed to this piece.

Codi is a freelance journalist, photographer, and researcher. Her personal work focuses on how emerging technologies change human relationships and the impact of tech platforms on journalism, civic discourse, and democracy. http://www.codihauka.com/

All photos by Codi Hauka