“The achievements of the Japanese . . . have been cried down by the newspapers. But that’s only to say foreign news appearing in American newspapers is seldom accurate and not always honest. In large part, it is written by bitter partisans, and not a few of them seem wholly unable to distinguish between agreeable fantasies and objective facts.”

—H.L. Mencken, “A Word for the Japs,” The Baltimore Sun, August 13, 1939

[T]he Holy Terror from Baltimore had never set foot in Japan. But he understood instinctively that news from war-torn China often crossed the line into anti-Japanese propaganda. With Japan’s army sweeping through Shanghai and Nanking in an orgy of rape and slaughter, the facts were horrible enough. But what editors at the Hearst publications and Henry Luce’s TIME wanted was support for their friends in China, i.e. the Christian missionaries and the U.S. business community who then, as now, saw China as the world’s largest market for souls to be saved and profits to be made. American reporters in China were thus encouraged to go beyond the facts and adopt broad, sweeping generalizations about the behavior of the Japanese race.

The reports both Mencken and U.S. readers were fed represented the continuation of, rather than the exception to, a long tradition of Western journalism on Japan. After the West’s first Asian correspondent, Marco Polo, returned to Europe with tales of the mysterious Orient, an editorial policy slowly evolved for those who did follow-up reporting. Asia, and particularly Japan, was presented as The Other; a mysterious region diametrically opposed to Western civilization. When Francis Xavier arrived in Kagoshima in 1549 to spread the Gospel, Japan was fixed in the minds of the Western clergy, the most influential editors of the day, as a land of mythical beasts, castles of gold and rare gems, heathen natives who ran around naked and practiced strange rituals. . . in short, an alluring Shangri-La of all of the things that had to be classified, controlled, and, where necessary, edited for a God-fearing Western audience.

The exacting approach of the clergy differed in some fundamental ways with that of the merchant classes, who just wanted to do business. For them, Japan was a bizarre bazaar, often less inhibited than the world they left behind. A man could seek his fortune in the richness of Japan, where the streets were paved with gold, and where the ladies offered a special exotic charm that had to be experienced to be believed.

Thus, in the centuries following Marco Polo, two schools of thought towards Japan, which might be dubbed the Missionary and the Merchant, were born. The schools were not mutually exclusive ideologies but distinct approaches to understanding and explaining to the folks back home who the Japanese really were.

There were, however, fundamental differences. The Missionary School treated Japan philosophically, respecting aspects of Japanese culture but convinced the natives would be truly civilized when they had become Christian. The Merchant School was less concerned with spiritual dogma and intercultural theories. It relied on a universal language — money — as the primary form of communication and understanding.

The Missionary School reports ranged from high praise when it appeared the heathen were on the edge of conversion, to bitterness when they decided not to accept Jesus in their lives. The Merchant School’s reports on Japan contained less dramatic written prose (but, in the company of good friends, lusty tales of gold and girls). Their works were tinged with amusement or amazement at non-Christian customs rather than hostility. Both schools were to prove not without merit. The Missionary School encouraged a rigorous academic approach to understanding Japan while the Merchant School encouraged mutual cooperation and made for good diplomatic relations. Throughout Japan’s so-called Christian century (1549-1640), the Western world was exposed to both schools of thought. But it was the Missionary School that got the most attention among the powers-that-be. Missionary journalists dwelled on the “potential” for the Japanese to become “enlightened” but felt obligated to remind readers, through indignation at various native customs, that there was still much work to be done.

When Japan closed to the outside world in the mid 17th century, having decided that the nosy Church reporters were inciting the masses to an uncomfortable degree, the Missionary School had to make do with second-hand sources and pen op-ed columns along the lines of “Whither Japanese Christianity?” The few Missionary reporters who landed on Japan’s shores during this time hoping for a chance to interview the locals were either flogged and executed or deported.

It was here that the Dutch, who offered lots of dry, scientific reporting and shunned investigative journalism, managed to get the media monopoly on information to and from Japan. The Dutch were firmly part of the Merchant School. They convinced Japan’s leaders that keeping up their subscription to the Dutch World News Service would ensure a noncontroversial and profitable-for-all-concerned content provider. Dutch reporters, in turn, agreed, on pain of loss of exclusivity (and of life), not to say or write anything that would arouse the locals.

Thus, for next 200 years, official reports from the Dutch enclave at Dejima in Nagasaki had all the excitement of a government White Paper on sewage disposal. Of course, in private correspondence, the Dutch groused about the difficulties of being a Japan-based reporter, problems which, 300 years later, sound familiar to some foreign hacks: lack of access to official sources, a reluctance on their part to say anything of interest even when they did speak, and an inability to learn Japanese due to the difficult nature of the tongue and the guardedness of native interpreters jealous of their special status.

While the Dutch provided perfunctory details about commercial transactions, spiced with the occasional shocked or amused vignette about the habits of the natives, the Missionary School wrung its hands in frustration. Denied access to primary sources, they resorted to spreading tabloid stories about a country virtually no one in Europe had ever seen. Over the years the legends grew, and with them curiosity. Finally, when Japan reopened its doors to the West in 1868, a second wave of foreigners rushed in. Missionary-like in their zeal to discover and “educate” the heretofore mysterious Japanese, they were not, like the Roman Catholics of old, ordained men of one faith but a diverse, non-denominational lot that ranged from Puritans to atheists: stern military officers, prim and proper English teachers, vagabond writers, con artists peddling every conceivable scheme, distinguished diplomats, gamblers, thieves, escaped criminals, drunks, respected corporate titans and a hundred other types.

What they had in common was an urge to explain, either in serious magazines or pulp fiction novels, how Japan was different, innocent, and bizarre compared to Victorian England or the America of Teddy Roosevelt. Lafcadio Hearn, a journeyman writer of little previous note, became one of the most widely read chroniclers of Japan. Others, from a diplomat’s wife who wrote about her travels around Japan to a military officer who penned a small work entitled My Musume — a whimsical account of his marriage to a Japanese woman — set the tone. The assumption on the part of the writers was that Japan was a quaint Lilliput, but one seeking to embrace Western civilization.

But the reporting soon turned from wondrous to nasty. As the 20th century progressed, a wave of Japanese immigration to the U.S. sparked racist sentiments. At the same time, American and European attention and sympathy turned toward China. U.S. businesses, afraid the European colonial powers would keep them out, insisted on an open-door policy for China and used their considerable clout with the media to ensure favorable reporting.

Anti-Japanese sentiment was also fueled by resentment, as Japan had gone from star pupil during the Meiji period to a threatening rival for power in Asia during the Taisho and Showa periods. During the 1930s, the U.S. media could find little good about Japan. Immediately after Pearl Harbor, one of the first institutions to take advantage of hostility towards Japan was Hollywood. Frank Capra’s “Why We Fight” series of movie shorts was explicit, racist, and very effective in mobilizing U.S. anger. From 1941 to 1945, as reports filtered back about Japanese war atrocities against U.S. troops, hatred of Japan rose to the point that, by the end of the war, few in the U.S. media questioned the president’s decision to drop two atomic bombs on civilian populations.

What followed was, perhaps, the Missionary School’s high water mark, as the Merchant School, with its emphasis on getting along and just making a buck, was discredited. Fresh-faced reporters who arrived with the American Occupation had the reformist zeal of Xavier and a military backing he could only have dreamt about. The media followed the fundamental tenet laid down by Editor-in-Chief Douglas MacArthur: Japan had taken “a wrong turn” in the 1930s towards militarism. Under U.S. guidance, it would once again become a model democracy. Later, when it became necessary to portray Japan as a staunch U.S. ally in the fight against communism, the Missionary reporters hailed Japan as a “democratic nation and bulwark against communist expansion.”

The view of Japan as America Jr. remained largely intact until Toyota, Sony, and Panasonic began receiving blame for putting American workers on the dole. In the late 1980s, as the Cold War faded, the Missionary School found itself challenged, not by the Merchant School but by The Four Heretics — two journalists (Karl van Wolferen and James Fallows), an academic (Chalmers Johnson) and a U.S. government official (Clyde Prestowitz) who argued the Occupation view of Japan as “just like us” was wrong and that the Editor/Priests ordained during that time were writing about a country that did not exist. Japan, they argued, was not like the U.S. and never would be.

Who, exactly, where the members of this new version of the Missionary School? Largely, they were young American journalists working with the wire services and the major newspapers who had crawled their way up the Pacific Islands with the Marines, watched as Japanese kamikaze pilots dive-bombed into ships and shuddered in horror as civilians jumped from the cliffs of Saipan. They arrived in Tokyo in September 1945 grateful to be alive, and determined to do their part in making sure Japan never threatened anyone again. As the years passed, they moved from reporting to editing, becoming Editor/Priests who reflected, rather than questioned, U.S. goals at democratizing (the 20th century word for “civilizing”) Japan.

The Four Heretics were greeted with hostility in the academic world, which, at that time, consisted of many U.S. professors who had served with the Occupation and who had spent the Cold War painting a picture of Japan as a modern democratic state that adhered to free market principles. More importantly to the U.S. State Department and the Pentagon was the fact that Japan continued to host nearly 50,000 U.S. troops. Many in Washington D.C. joined American Japan scholars in condemning the views of the Four Heretics out of fears, real or imagined, that they posed a danger to the U.S.-Japan security relationship. But the Four Heretics found a ready audience among some in the U.S. mass media, and were to have a profound effect on the way the Western media dealt with Japan and the forcefulness of their views shook the Occupation Editor/Priests. Younger U.S. reporters and editors felt the Heretics, not the grizzled Occupation vets, had a better handle on the “real” Japan. Every new Japanese political and business scandal seemed to provide supporting evidence that, no, in the end, Japan was not a Western style democracy but a unique system not necessarily compatible with the rest of the world.

Today, ten years after Japan’s bubble economy burst, the intense clash between the Occupation Editor/Priests and the Four Heretics has faded. In its place has arisen greater demand for “just the facts”, and the Merchant School finds itself somewhat back in vogue. Where just a few years ago, U.S. reporters would try to explain the “real” Japan based on one school or the other, today, they are more likely to offer reports on Internet users and the number of failed banks. On military issues, the Occupation Editor/Priests do continue to inspire devotion among American scribes, who write about how quickly the region would descend into chaos without the Marine presence on Okinawa. But these claims are under serious questioning elsewhere. Meanwhile, the more dire warnings of the Four Heretics about Japan taking over the world sound outdated and foolish.

Of course, the technological changes of the past decade now mean that a handful of Western media are no longer the sole means by which information on Japan reaches the outside world. But they are still the main source of information for the movers and shakers in New York, Washington, London and Continental Europe, and, by extension, those who are moved and shaken. A New York Times or Independent piece on elevator girls and teenage prostitution, or a BBC piece espousing the latest electronic gizmos in Japan, have much more of an impact on public policy than less influential, but better informed, media reports on the problems of Japan’s elderly or the criminal negligence of the country’s nuclear power industry.

Thus, despite the changes and the multitude of information choices, the bitter partisans Mencken spoke of 60 years ago remain with us, influence perhaps weakened, but still fighting to shape the West’s intellectual approach towards Japan and still providing readily accessible intellectual, spiritual, and economic comfort stations for those who cannot be bothered to seek the “real” Japan for themselves.

Eric Johnston is Deputy Editor for The Japan Times Osaka office and veteran of UN conferences in Japan and abroad, including the 1997 Kyoto Protocol conference and the 2009 Copenhagen conference. He covered the 2010 COP10 conference in Nagoya for The Japan Times, also contributing significantly to KJ’s special issue on Biodiversity, produced for that conference.

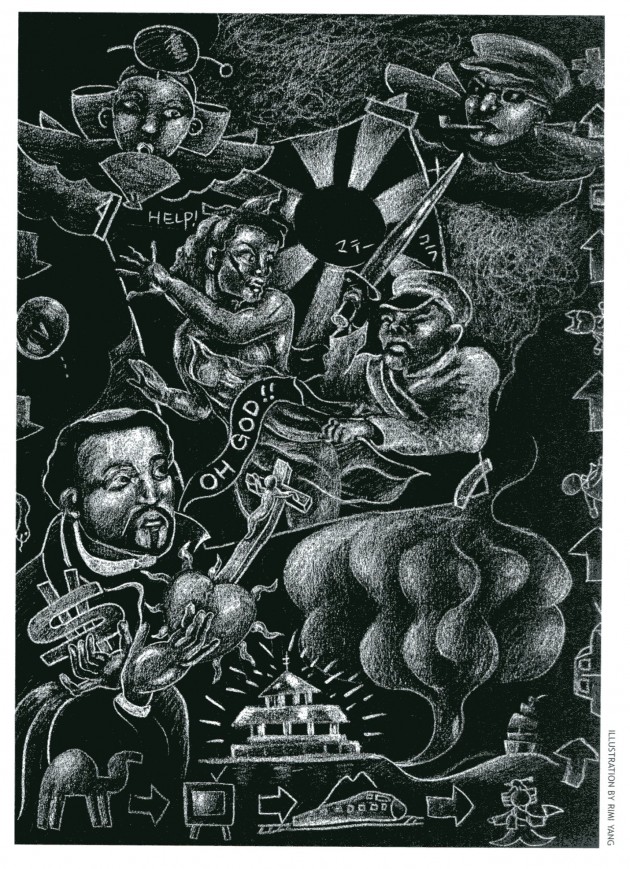

Artwork by Rimi Yang