By Gunter Nitschke

Excerpted from a two-part article published in KJ 12 & 13 (Fall & Winter, 1989)

With the death of Emperor Hirohito in 1989, the 64-year Showa Era (era of “enlightenment and peace”) came to a close. The new era, Heisei (“achievement of peace”) was immediately proclaimed. Tens of millions of calendars were discarded and replaced as the nation literally went back to year one. Time has been renewed.

Through its rituals, Japanese society marks both historical time, that is, progressive irreversible time, and natural time, the cyclic eternal rhythm. Historical time was originally reckoned by counting the years from the enthronement of each emperor. Later, many special new eras were proclaimed at irregular intervals for reasons other than succession. Each of these eras has its own name (gengo, “origin marker” or nengo, “year marker”), consisting of two ideograms. This mode of measuring historical time was used in imperial China from 163 BC, and was introduced to Japan with the Taika Reform in 645. In 1867 it was decided that a nengo could begin only with the reign of a new emperor. Today the Christian year, e.g. 1989, is known by all Japanese and sometimes used, but it is the nengo year, Showa 64, which is generally used for everything from official documents and newspapers to automobile models. The Showa Era was the longest in Japanese history.

Renewal of historical time through renewal of the divine monarchy is effected with three sucession ceremonies. First, immediately after the demise of the emperor, are the rites of ascension to the throne and the transference of the sword and jewel which symbolize the Chrysanthemum Throne. Then the civil accession rites are celebrated after a year of official national mourning; these are of purely Tang Chinese character, adopted in the second half of the 7th century.

Finally the indigenous Japanese enthronement ceremony, the Daijosai or Great First Fruit Tasting Rite, is held. Traditionally it took place one to two years after the civil rites, but since 1915 it is held during the following autumn. The Daijosai is a religious festival in a class of its own, the highest Shinto ritual, according to the classification of festivals in the Engishiki of 927.

Emperor Hirohito declared himself a mere human being on New Year’s Day in 1946, and the state is expressly separated from religion under the present Constitution of 1947. But previously (and still, in the minds of many Japanese) divine rule rested on the myth that the imperial house is descended from Amaterasu-omikami, the “Heavenly Shining Grand Deity” or the Sun Deity for short. That is the story which appears in the oldest indigenous chronicles, the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) of 712 and the Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) of 720.

The divine body (shintai) of the Sun Deity, represented by a mirror, is housed at the Ise Shrine. This mirror is the third symbol of the throne. According to the chronicles, it was originally enshrined and venerated in the imperial palace, but was moved during the reigns of Sujin and Suinin (first centuries BC and AD) to various places on a long journey to the present site. From that time onward, ritual worship of the Sun Deity has been performed at Ise three times each year by the saio (consecrated princess), a daughter, niece or granddaughter of the emperor who officiates as chief priestess on behalf of the emperor and the nation.

The buildings of the Ise Shrine are presently being replaced for the 61st time, in an eight-year process that will be completed in 1993. This Shinto ritual, called Shikinen Sengu (Periodic Renewal of the Imperial Grand Shrine), is completed every 20 years. It was institutionalized by an imperial rescript recorded in the Engishiki, and by an older rescript of Empress Jito in 688 which is not extant. Recent research indicates that the first renewal of the Inner Shrine, dedicated to the Sun Deity, took place in 690, and that of the Outer Shrine, dedicated to the Food Deity, in 692; the earliest renewal recorded in the shrine records, however, was in 785. (Although the term Shikinen Sengu also applies to the renewal of certain other shrines, it is used here to refer only to the Ise rites).

Through the Shikinen Sengu, which in structure resembles one agricultural ritual year extended over eight years, natural time—time perceived as the eternal return of the seasons—is renewed by the cyclic reconstruction of Japan’s supreme sacred space, the shrine grounds of the imperial ancestors.

These two great rites of renewal, the Daijosai and the Shikinen Sengu, in ways which are outlined in this essay, resolve the ultimate “disease” of time, both historical and natural: the yearning for sacred authority and sacred architecture to be extremely ancient, yet ever pristinely fresh.

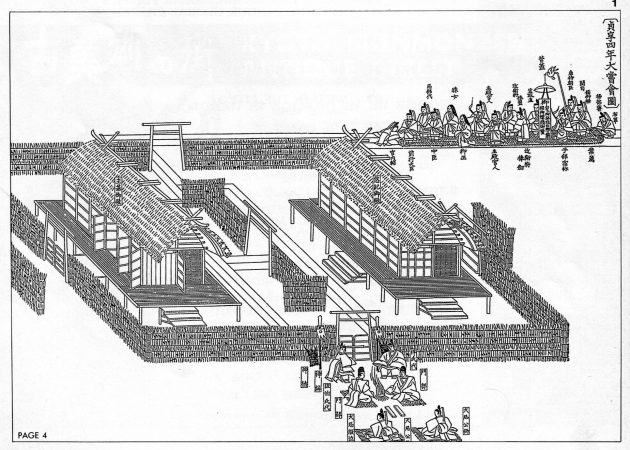

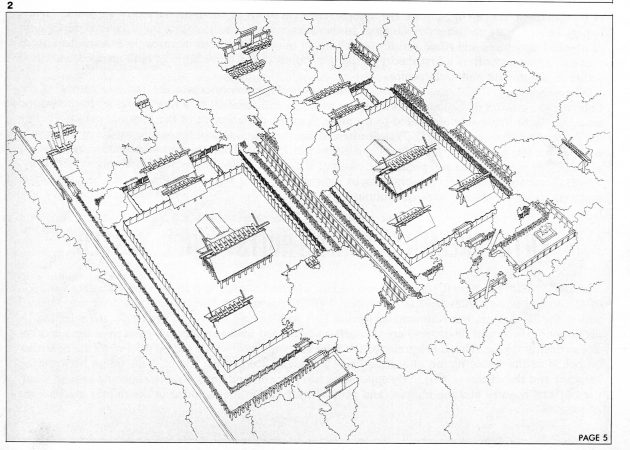

Renewal is a phenomenon in time. The occurrence of one thing after another in the temporal dimension is most simply expressed in space by placing things side by side. The two identical temporary lodges built for the Daijosai (fig. 1) and the two identical sets of structures on adjoining sites at the completion of the Shikinen Sengu (fig. 2), are the spatial representations of the most sacred of Japanese values, imperial sovereignty and ancestor worship. In these ceremonies we discover a multi-layered duplication of physical structures and ritual actions, which might have its justification precisely as a mechanism of renewal. This essay offers a first theory of the implications of the duplication of built artifacts and ritual action in Shinto rite and architecture.

The only other official rite of renewal related to the Japanese ruler was the Sento (Removal of the Capital), the custom of building a new capital with the enthronement of a new emperor. In prehistoric times, the Sento probably amounted to no more than the replacement of the imperial palace. During the Asuka and Nara periods (552-794), it often meant the rebuilding of the whole capital at a different site. Since the building of Heian-kyo (now Kyoto) in 794, the Daijosai rites of accession have served as a quasi-reenactment of the prehistoric custom; the palace alone is renewed, but only symbolically. The Daijosai appeared in its present form at approximately the time when the Sento, the institutional replacement of the capital, was discontinued.

ENTHRONEMENT: FIRST FRUITS TWICE TASTED

The Daijosai, the “great” first fruit tasting rite, celebrated once in a reign, is an elaborate variation of the annual harvest rites held at the imperial court, the ancient Niinamesai (new fruit tasting rite), and at the Ise Shrine, the Kannamesai (divine first fruit tasting rite). The first act is the selection by divination of two rural districts where rice will be cultivated under strict ritual rules over the period of one agricultural year. This is the grain for the food and wine sake which will be offered by the new ruler on behalf of the whole nation at a great harvest festival, a nocturnal rite of communion between the emperor and the deities (kami). By appointing two plots of land and two sets of people to tend them, the physical country and the human (and geopolitical) nation are included in the duplex mechanisms of renewal.

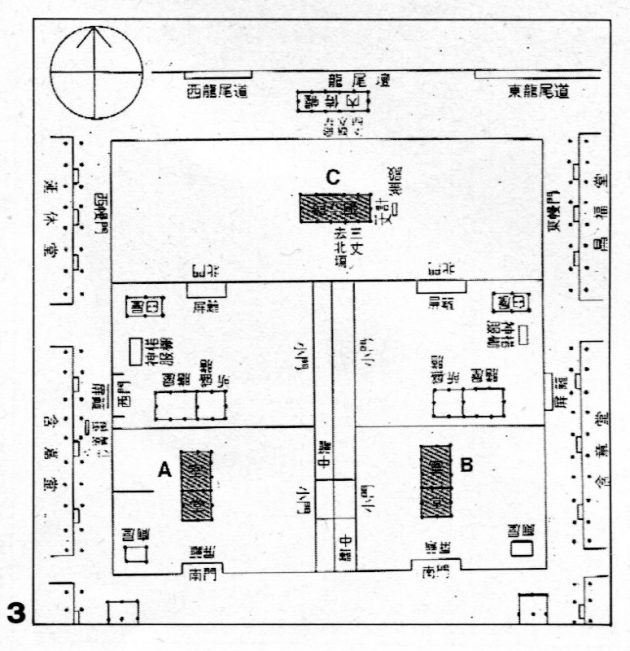

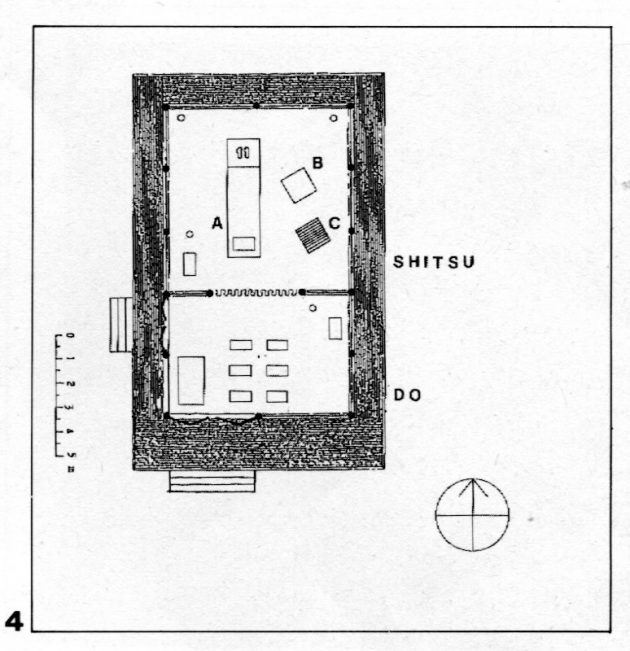

The selection of two sacred plots of land is echoed in the dual layout of the Daijogu (Great Harvest Palace), which is erected five days before the night of the rite and dismantled immediately afterward. According to Professor Masaru Sekino’s copious analysis of the Jogan gishiki (Ritual Guide of the Jogan Era), in the 9th century this temporary ritual palace must have consisted of about 90 primitive buildings arranged in two identical sets, each with a larger outer and smaller inner precinct, allowing a separate building for each function, as at Ise. Only the three main components of the inner precinct are built as the Daijogu nowadays, at the Kyoto Imperial Palace. There are two identical primeval lodges, the Yukiden (Hall of Purity) to the east (fig. 3A) and the Sukiden (Succeeding Hall of Purity) to the west (fig. 3B); and the Kairyuden (Hall of Recurring Flow) to the north (fig. 3C).

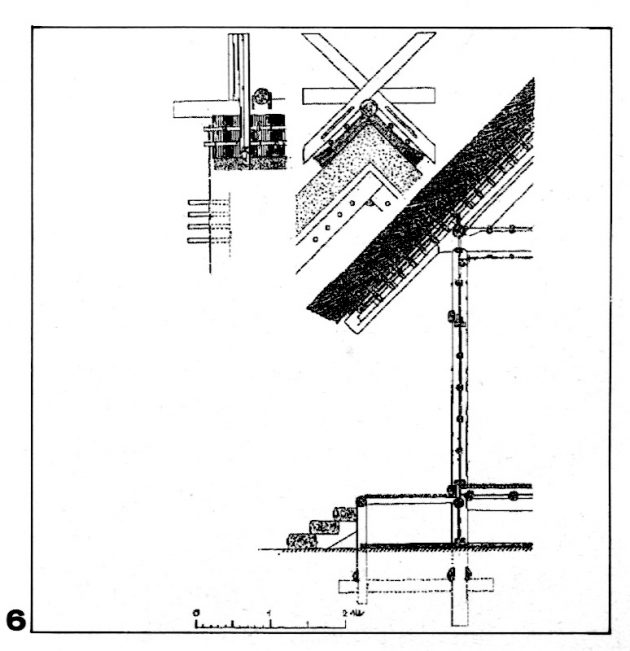

The architecture of these three buildings recreates the earliest dwelling or “palace” architecture of Japan: The structure is of pillars of unpeeled timber sunk into the ground, with reed thatching and grass walls, and the ridge is ornamented with chigi and katsuogi (fig. 6). The floor is raised from the ground, although not as high as in ancient granaries, which are usually regarded as the pattern for the Ise Shrine buildings. Finally, the plan, measuring two bays by five, is divided into a two-bay-deep antechamber (do) and a three-bay-deep inner chamber (shitsu) (fig. 4). The recurrence of these structures at the start of each new reign is a ritual transport back to the origin in Japan of, if not building, architecture as such.

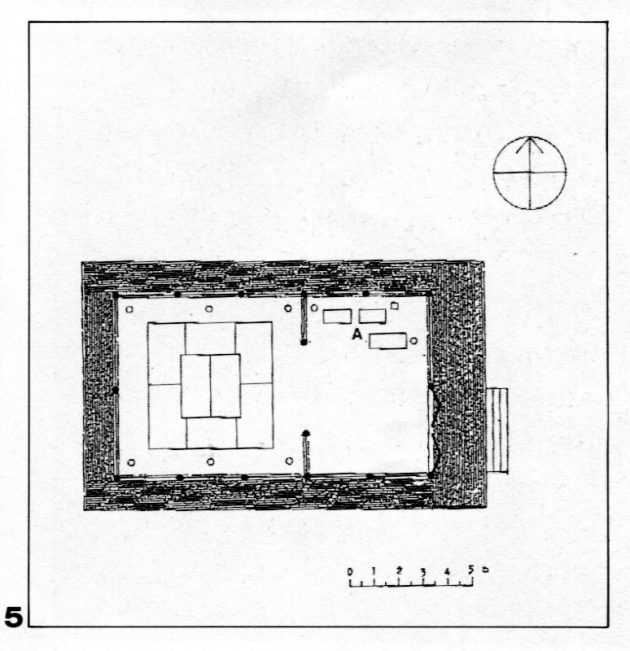

The Daijosai proper is preceded by the Chinkonsai (rite of quietening the spirit) performed by the emperor the day before and followed by the Enkai (festive banquet and dances) the day after. At the climax of the Daijosai, at 8 p.m., the emperor takes a ritual bath in an onyu no June (hot water boat) (fig. 5A) in the Kairyuden building, puts on a white silk ame no hagoromo (heavenly feather coat), proceeds barefoot on a carpet which is unrolled in front of him to the Yukiden, and seats himself in the inner chamber beside the shinza (deity seat), a bed of three piled-up pressed straw mats, facing a food offering table to the southeast, the direction of Ise (fig. 4). To an accompaniment of kagura (divine music) he first offers the food and wine supplied by the Yuki district to the deities, and then, symbolically, partakes of them himself. Around midnight the emperor returns to the ablution hall where he again bathes and changes his garments, and from 2 a.m. he performs an identical rite in the Sukiden.

The mysterious duplication of the structures and ritual actions, which is the theme of this study, is explained by D.C. Holtom as follows: “In the primitive situation, at the death of a ruler the successor purified himself, went to the dwelling of the dead Emperor, secured from the couch-throne the three sacred regalia, and carried them, after a second purification, to a new dwelling which he had built for himself The Daijo-sai dramatically re-enacts this primitive procedure. The Yuki Den stands for the dwelling of the dead Emperor, the Suki Den is the dwelling of the new Emperor.” In this sense the Yuki district should symbolize the domain of the dead emperor and the Suki district that of his successor.

Succession in time displayed ritually in space results in side-by-side placement of two dwellings. The same phenomenon is visible in the last stage of the Shikinen Sengu, during which the old and new shrine complexes coexist on adjacent plots (fig. 2). Even under ordinary profane circumstances, one must have a new abode before moving away from the old one. It would follow that the Daijosai rite of renewal for Japanese sovereignty is not only of agricultural character as a harvest festival, but also has territorial origins.

Disagreeing with Holtom’s theory, R.S. Ellwood interprets the Daijosai rather as “a visit to female kami” by focusing on the presence of a bed in the lodges. He emphasizes the theme of Hieros gamos, sacred marriage. “The marriage is at once heaven with earth and the sovereign with his (womanly or spiritual) consort; the child is at once the harvest and the next heir to the throne.” For Ellwood, the Daijosai is mainly a “marriage feast.”

Admittedly, such a theme is obviously suggested by the couch throne and the nocturnal schedule, which is hardly suggestive of any sun cult. This may point to a strain of symbolism in the Daijosai which preceded its obvious agricultural elements. But an interpretation of the ancient Daijosai as marriage feast throws no light on the strange duplication visible in its architecture and enacted in its ritual, unless one assumes the ruler originally slept with a heavenly or earthly maiden once before and once after midnight, or with different ones in the evening and the morning, with a bath in between.

The Daijosai, the indigenous rite of renewal of divine kingship, is definitely tied to ancient Japanese harvest festivals in general, and to the Ise cult in particular. Hence a closer look at the renewal of crops in the annual liturgical agricultural cycle of the Ise Shrine might be revealing for our purpose.

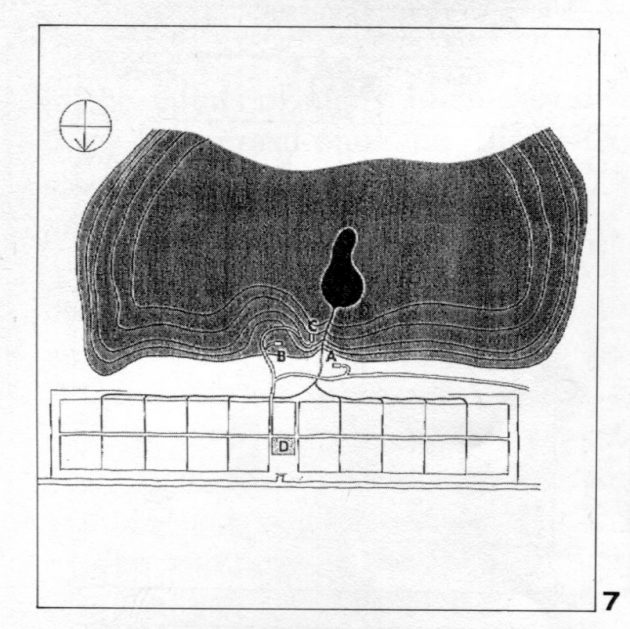

The rice and sake which are dedicated to the Sun Deity at Ise, in rites performed every morning and evening, and during the Kannamesai harvest festival and two other major annual festivals, are prepared from grain grown in the shinden (divine fields) situated some distance north of the shrine, at the foot of Yukuwa Yama (Taboo Hoe Mountain). These fields present a model of the Japanese agricultural topography and an archetype of the ancient sacred precinct. The elements are clear: mountain, water, fields and a torii (“bird roost”), the trademark Shinto gate signaling the main passage into a sacred domain and separating it from the profane world of human settlement (fig. 7).

The Shinden Gesshusai (rite of bringing down rice seeds and sowing them in the divine fields), is the first of a sequence of rites leading to the annual Ise harvest festival, held October 15-25. The rite is of ancient origin; it is described in both of the oldest extant sets of ritual regulations, the Kotai jingu gishiki cho of 804 and the later Engishiki. It is held in early April, at four designated places within the shinden field precinct.

First, the attending priests and farmers, along with three wooden boxes containing the seeds, offerings and ritual tools, are purified at the haraisho (purification place) at the foot of the mountain (fig. 7A). Next, food and a norito (Shinto prayer) are offered to the mountain deity at the yamaguchi-saijo (festival place at the mountain mouth) (fig. 7B, 8), at the end of which a consecrated young boy performs the symbolic action of cutting grass with a sickle and opening the ground with a hoe.

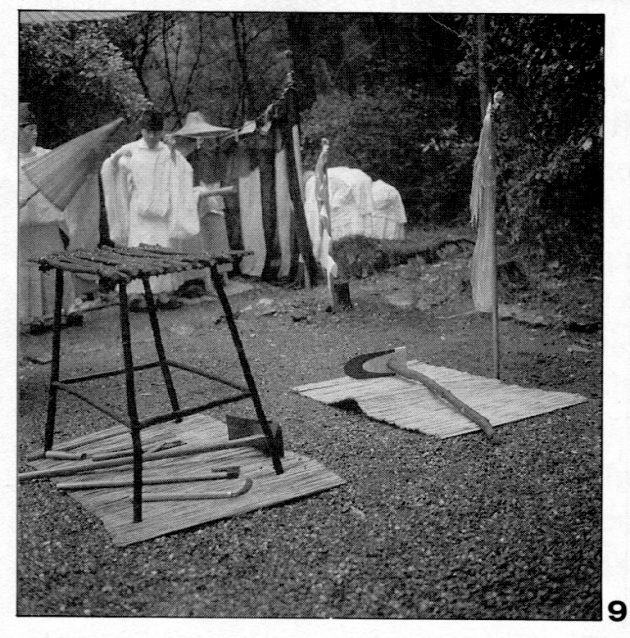

Then the retinue moves slightly higher up the mountain to the konomoto-saijo (festival place at the tree source) (fig. 7C), where the tree-source deity is offered food and a prayer, a small box of katashiro human effigies is buried beneath the tree, and the boy again performs the symbolic cutting and hoeing. At that point a small tree is felled and formed into the handle of a new metal hoe. The new hoe is then laid in front an old one under the offering tables, as if here also renewal is best stated visually by juxtaposing the old and the new. (fig. 9).

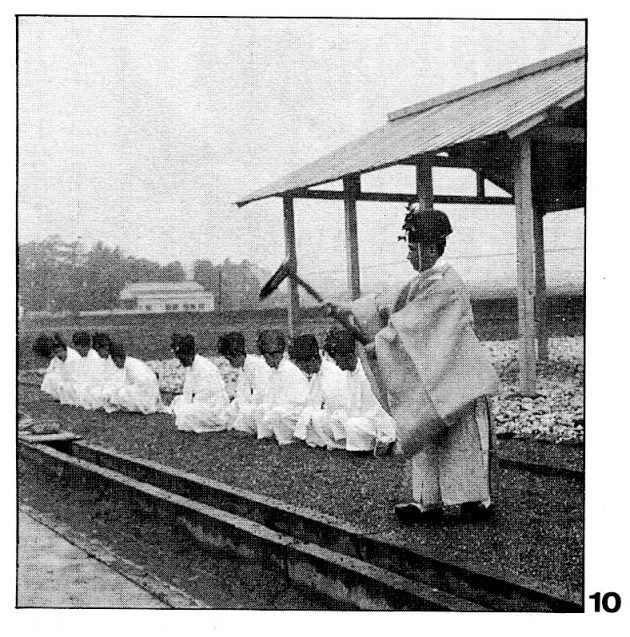

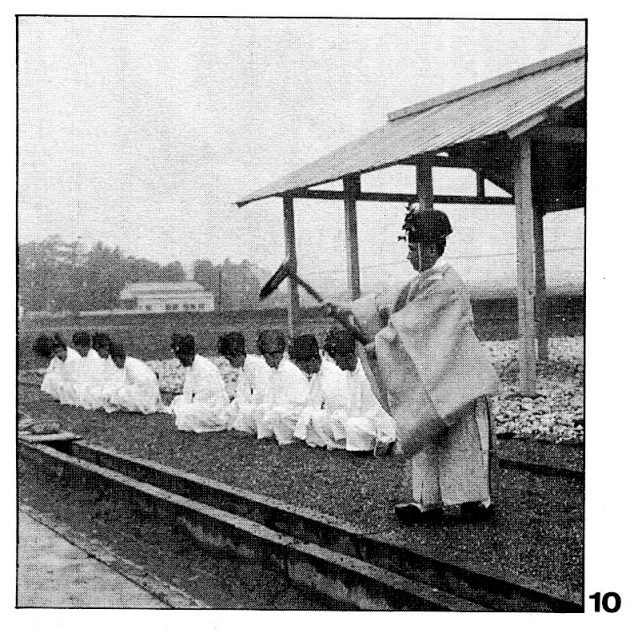

Decorating their hats with mountain creepers, everyone descends to a saijo (festival place) in the middle of the rice fields (fig. 7D). Here the new yukuwa (taboo hoe) and yudane (taboo seeds), on two tables one behind the other, are consecrated, food is offered and a prayer recited. An assistant to the priests swings the new hoe and then the rice seeds over the edge of the prepared fields (fig. 10). Then the actual sowing is done by the farmers while the others intone an ancient song: “Heavenly hoe / wearing a hat decorated with creepers, / the shrine folk at spring / celebrate in the august field.”

The belief that local guardian deities live in the mountains in winter as yama no kami (mountain deities), and are brought down in spring to energize and protect the crops as to no kami (field deities) until they are sent back in autumn, is spread all over Japan and ritually enacted in many farm communities up to the present time. The descent of the kami is typically visualized by bringing down a whole tree or a few branches, and their send-off back to the mountains by lighting fires.

The Shikinen Sengu, the vicennial rites of renewal of the Ise Grand Shrines, start on a day in May with a similar Yamaguchisai mountain rite in the morning, and a Konomotosai at 8 p.m. during which the first tree for the shrine construction is felled. It ends in October eight years later with the Sengyo (rite of transference). At that time the deities of the Ise Grand Shrines are presented not only with the new crops and new sake, but a whole new “suit” of buildings, too. In structure and rite the Shikinen Sengu imitates the ritual agricultural year. But the tree-taking ritual is shrouded in secrecy and held at night. The felled tree becomes one of the two holiest of holies at Ise.

The question which remains is what was originally brought down from the mountain as the kuwa in the Ise rice-sowing ritual: a new handle of a metal hoe, as today, or a new wooden hoe, or just a staff or tree. In this respect I can only point out that in such ancient texts as the Harima fudoki, the term kuwa signifies a land occupation mark in the form of a wooden pole.

FIELD DEITY: TRANSPLANTING

The next ritual stop in the annual rice production cycle in Japan is usually connected with the transplanting of the young rice shoots into the paddies, a festival that is still held at Ise and many small local shrines. It is celebrated on June 24 in Isobe at one of the five bekku or outlying shrines of the Ise complex, Isawanomiya, which dates from the time of Emperor Suinin, and enshrines the “august spirit of the sun deity. The miryoden (august rice fields) lie about 100 meters south of a small wooded hill concealing the actual shrine buildings. The fields, like the “divine fields” of the Inner Shrine, are an archetypal image of the ancient Japanese sacred precinct.

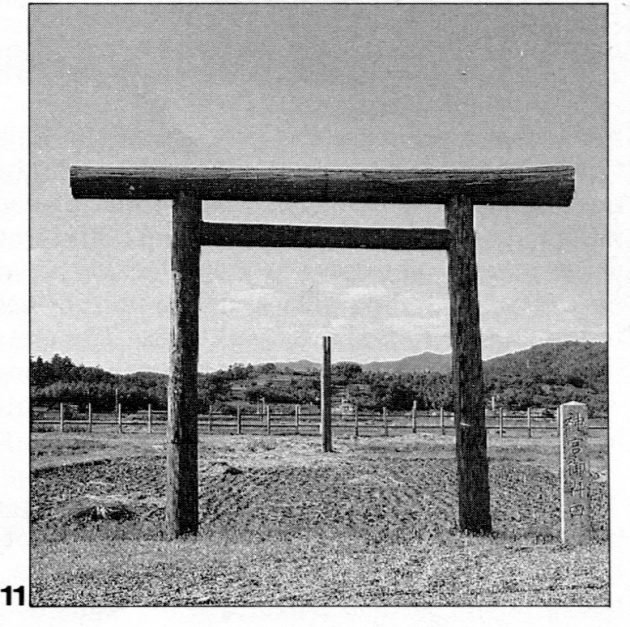

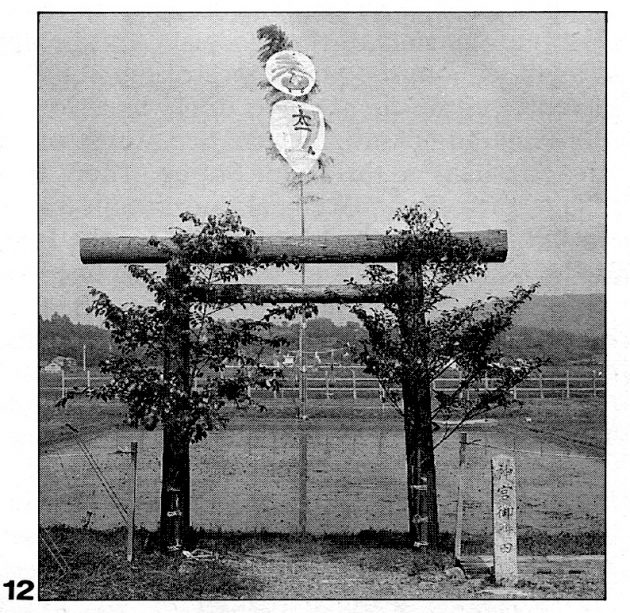

A space at the center of the fields is marked on the east by a torii gate and on the west by a double pillar, two pillars bound together, of approximately the same height as the gate (fig. 11). These are brought “alive” for the ritual: the gate is decorated with fresh sakaki evergreen branches with a new shimenawa (sacred straw rope) connecting them at the top; while a ten-meter-high new bamboo pole is bound onto the double pillar and adorned with painted banners portraying a treasure boat and the ideograms for dai-ichi, “great first”, (fig. 12) a symbol used for the Sun Deity in Ise. According to a recent study by Hiroko Yoshino on the Daijosai (1987), dai-ichi was adopted by the Japanese Imperial Court as a term for their highest ancestral deity, Amaterasu Omikami, from Chinese thought. In China the same term was one of the names for the north polar star, the supreme deity in ancient Chinese cosmology. Therefore, in the layout of the capitals and palaces of China and later of Japan, and finally in the layout of the Imperial Ancestor Shrines in Ise, the seat of power and respect was always in the north.

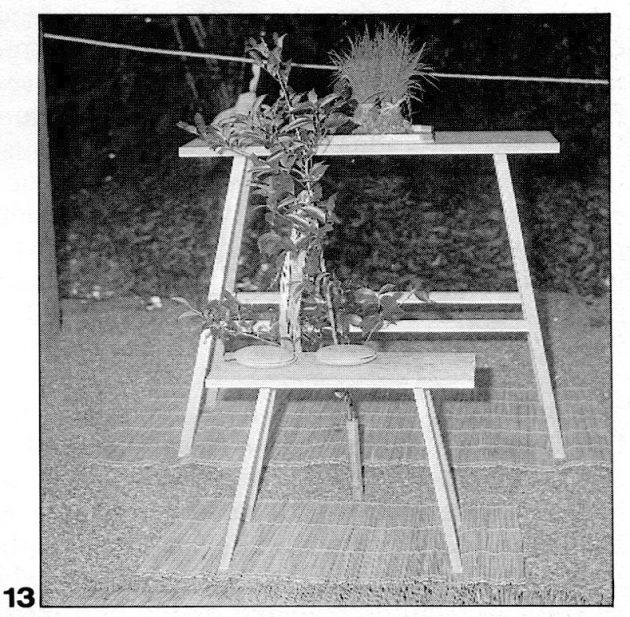

The ceremony begins at the upper shrine grounds with the purification of two bundles of rite shoots and of the attending priests, farmers and fishermen (fig. 13). Then the rice spirit represented by the two bundles of shoots is carried in a solemn procession down to the sacred fields. The action at first centers on the bamboo pole, which is slowly lowered and swung over the inundated opened ground and finally dropped into the mud. A group of naked fishermen—the festival being equally celebrated by the rice farmers and the fishermen of the nearby villages—then fight for a piece of it. Such mudfight rituals are still performed in the spring in many places. The logic here is that once a year one should taste directly the very mud from which one is made and nourished (fig. 14). A fishermen who captures a piece of the pole will proudly fix it to the center of his boat as the funadama (boat spirit) to secure a rich catch in the coming year. The ceremony concludes with the actual transplanting of the rice shoots by rows of festively dressed maidens. Ancient field music is intoned, and a young boy is pulled in a wooden boat-shaped vessel in front of the advancing line of planters.

It is difficult to state which is most captivating, the simple archaic building and marking of a sacred precinct, or the clarity of the ritual action. Both echo the Nature Shinto of the distant past before permanent shrine buildings.

In the Ise sowing rite, the deity is invited down from the mountain in the form of two hoes, old and new; in the Isawanomiya transplanting rite, in the form of two bundles of rice shoots. The unanswered question, which is never even raised in the Japanese literature, is the meaning of the double pillar. My theory is that in the original form of this rite, a single pillar was renewed, that is, replaced by a new one, freshly cut and brought down from the mountain like in Ise, and the older one was taken down and its pieces fought over as sacred talismans.

The Isawanomiya pillars resemble the two shin no mihashira buried respectively under the Inner and Outer Shrines at Ise. They stand separate and invisible for nearly 20 years on the two respective adjoining shrine sites, while those at Isawanomiya are joined and exposed to the eyes of the worshippers.

This article is featured in our Understanding Japan Bundle

GÜNTER NITSCHKE, born in Berlin, has degrees in architecture (Germany), town planning (London), and Classical Japanese (Tokyo). He taught East Asian architecture and urbanism at Princeton University and MIT full-time for 18 years, as visiting professor at UCLA and California State Polytechnic University at LA Pomona, and since 1987 for 20 years at Kyoto Seika University. As well as numerous critical essays in international professional publications, he has authored The Architecture of the Japanese Garden – Right Angle and Natural Form, (Taschen, Koeln, 1991) and From Shinto to Ando – Studies in Architectural Anthropology in Japan, (Academy Editions, London, 1993). He is also Director of the Institute for East Asian Architecture and Urbanism in Kyoto. http://www.East-Asia-Architecture.org.

This is an excerpt from a two-part article that was published in KJ 12 & 13 (Fall & Winter, 1989)