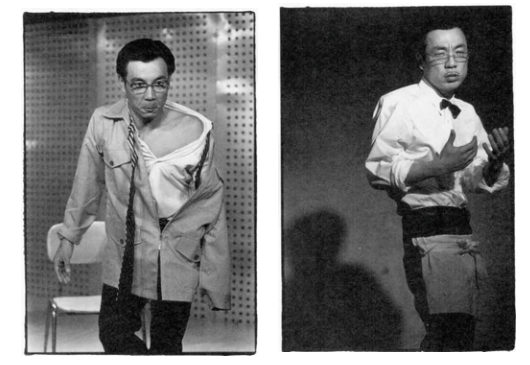

MONOLOGIST, TELEVISION AND FILM ACTOR, short story writer, illustrator, Issey Ogata is a renaissance man in the stratified world of Japanese arts. On stage, his breadth and depth are unparalleled and his artistry shows the marks of genius: original, immediately recognizable, and impossible to imitate.

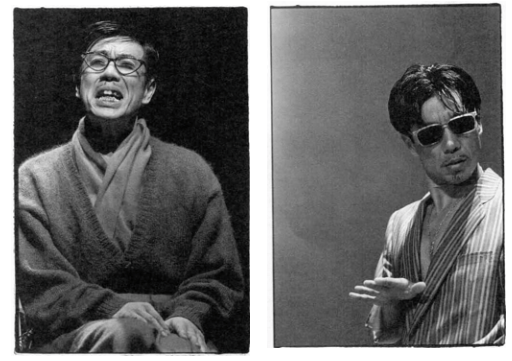

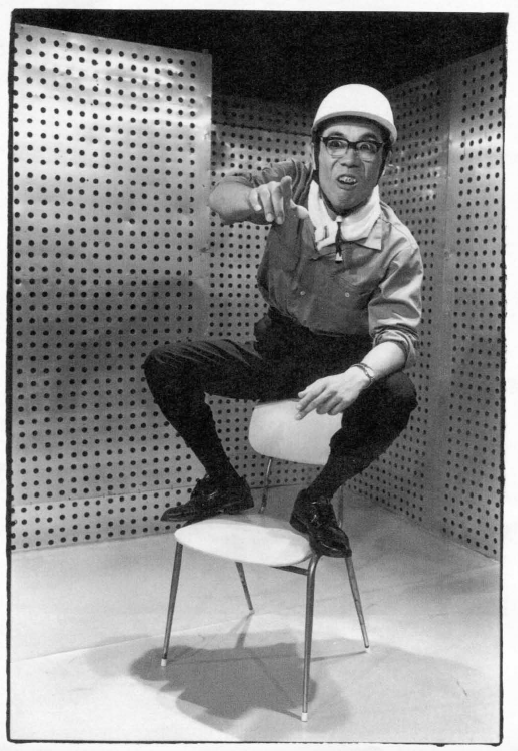

In the live performances which vaulted him to fame, Ogata introduces a human zoo inhabited by society’s male dropouts and down-and-outs: the failed salesman, unhappy lover, lecherous teacher, panhandler, ex-husband, lonely civil servant, workaholic father… A few of them keep reappearing as familiar friends, serial players in the lonely-hearts club band: the acerbic Bartender, the unemployed Man with the Eyebrows, the Born-a gain Evangelist. But most Ogata characters are one-timers, destined to make a quick, often indelible mark on an audience and never to return.

Many who admire Ogata’s work mention the ” backbone” to his art. Even the lighter pieces have profundity, and the heavy themes are tinged with humor. Always apparent is a respectful sympathy for the foibles and frustrations of modern man. It is fleshed

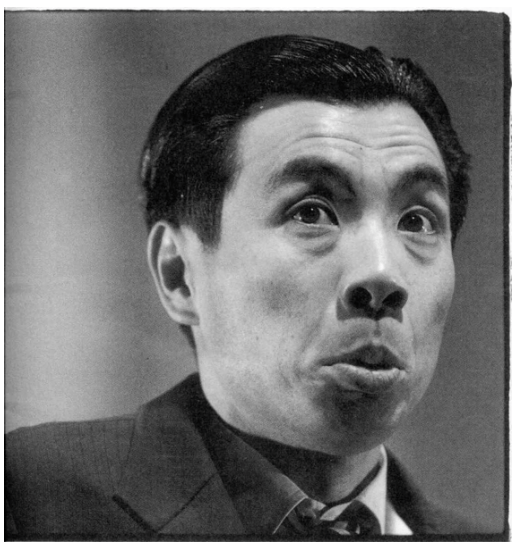

out with remarkable physical dexterity and expressive range, a chameleon-like ability to transform the face with a dab of make up or flick of a comb, and exquisite timing both within the scene and between performer and audience.

The Issey Ogata-live phenomenon is actually a full partnership between Ogata and director Morita Yuzo. Since 1971, when they met at an acting school in Shinjuku, they have worked exclusively together: Ogata’s live theatre is directed only by Morita, and Morita directs only Ogata (and his rare guests). Morita does not move all his attention to new works at the expense of established or classic pieces. He attends each performance and comments on it afterward, deliberately preventing Ogata from falling into habit. The result is that even plays seen on consecutive nights following viewings on video maintain their improvisational verve. The duo has created more than 200 sketches since 1980 and continue to produce new plays at the rate of a dozen a year.

Recently, Morita and Ogata have been moving away from realism, which they find too facile, toward a kind of postmodern absurdism which Morita describes as ” beyond Beckett.” Brain Control Band presents a man whose body won’t listen to what he tells it, whose spastic, robotic behavior threatens his very life. Hey, Taxi! begins with the realism of a drunk salaryman unable to find a cab and ends with the man stuck in the crack between two buildings and wondering if other unfortunates are lined up behind him. Audiences start out laughing, but soon change to nervous giggles, and finally become choked witnesses to a rather desperate loneliness.

Popular comedy in Japan has been restricted to a few established genres: the venerable, elegantly stylized kyogen farce; the virtuoso storytelling of rakugo; the vaudeville standup of manzai; and the broad slapstick of Yoshimoto new comedy. Ogata-Morita comedy was clearly nurtured in this environment of Japanese styles, but it is unique.

Like kyogen, the plays are about everyday characters, but Ogata’s rubber face opposes the deadpan of the kyogen actor, and his delicate mime is more suited to studio theatre than to broad-gestured kyogen’s outdoor stage. The intimacy of the 100- to 300-seat theatres where be usually performs a allows Ogata to bring the subtle gestures and inflections of real life to the stage. He shares with the rakugo raconteur a love for the weak and grotesque aspects of the human comedy but refuses to step outside them for narrative frame; he is not a storyteller; his character is the story. Nor do Ogata’s caricatures speak directly to the audience, in the standup or manzai style. They are observed through the “fourth h wall,” talking to a class, a wife or mistress, an interviewer, colleagues, or just to themselves. Mo re elegant than the standard, gag-heavy fare of the stylish new comedians, Ogata’s material stands largely on sustained dramatic force. There is a conscious effort by Morita to remove cheap laughs, to create laughter not through shtick or shock, but from recognition of the absurdly familiar.

In the 1970s, after acting in various productions, including plays by Pinter, Beckett and Brecht, Ogata became disillusioned with the realism and commercialism of shingeki (modern theatre). He worked for a time as a construction day laborer, and as a bartender, experiences which were to provide much of the raw material for his monologues. In his first solo play, put on in 1981 at the nightclub where he was working, he played a bartender opening the bar, chatting with the help, revealing his own neuroses, and closing up. That 90-minute show was elaborated to a series of 20-minute sketches which he presented in Tokyo clubs and small theaters. With director Morita, he added vignettes of loan sharks, drunken salarymen, barkers and others from the lower depths of the Tokyo night. Their characters and their telling physical quirks – a slouch, a leer, a grunted laugh- were delivered in Ogata’s trademark realer-than-reality style.

The first break came in 1981 when he won a gold medal on the television program ” A Co mic Star is Born!” Unlike the competition. Ogata’s sketches were remarkably free of gags, punchlines, farce or vulgarity. The appeal was limited, but those who liked him were fanatical. Ogata then began a series of performances in small theatres, consisting of six or more solo sketches of five to thirty minutes. Bet wee n acts, he would dress and make up for the next role right on stage, at once playing to the audience’s voyeurism and underlining the common, human source of all his characters.

It was Morita and Ogata ‘s principle at the time never to repeat a play on stage. This was partly to keep the material fresh, a rebellion against the slick shingeki long-runs, but mainly to please their small but loyal following. Yet they never put on an improvised sketch, sticking instead to well- rehearsed pieces with excruciating detail. In e effect, Ogata and Morita were creating the carefully defined kata, or formal pattern, which is the core of each of Japan’s traditional arts. Ln place of the usual generations of master to-disciple training, they tele scoped the process of forging the kata into a few intensive years of endlessly repetitive rehearsal, continuous directorial notes and incredible feats of memory.

An eager cult awaited the next in the “Urban City Catalog” series followed by “Issey Ogata’s Non-Stop Live.” They told their friends. Today a newspaper listing or a poster at the theater is sufficient to sell out a show within hours.

How has Ogata managed to touch the funny bone of Japanese from every class and region? He is not a gentle exposer, nor scathing satirist, nor parodist of stereotypes, but a prober at the boundaries of the Japanese sense of self. Ogata skates along the cracks of middle-class identity, and especially along the division of tatemae and honne. Tatemae is the ideal, the “front” presented to strangers and the public at large. Japan’s famous sensitivity to hierarchical distinctions, to inside/outside and to formal etiquette are part of the c crucial need to maintain tatemae. Honne is the true feelings, expressed only to close friends, family members, or oneself. Amid an exaggerated display of tatemae—the solicitous father’s pretense of enjoying the family’s once-a-year trip to the hot springs—Ogata injects a spurt of businessman honne—demanding that his wife drink her ” quota” of beer. The Midsummer Night’s Bartender uses his age and position to harass a waiter yet reveals his own restless insecurity beneath the bravado. In The Parking Lot a blue-suited young salesman is waiting to take a client out on the town, and when the client fails to appear, he rummages through his briefcase and pockets because he cannot recall his own name, or what company he works for.

To a people deeply accustomed to the s tress of putting up a front, a face, to the world, these glimpses of imperfect make up and armor gone awry are deliciously appealing. This is the Rea l Japan, where people caught in the white lies of tatemae are exposed in the full aching humanity of their honne. In his short plays as well as his caricatures, Ogata uncannily sums up the inner and outer man in an abstract yet hyper-realistic portrait. He shares with Daumier. Grosz, Bacon or Lucian Freud the ability to cut to the heart of the subject, exposing it with unflinching wit as well as indefatigable humanism.

Having proven themselves in venues all over the home islands, Ogata and Morita were anxious to see if their archetypal l Japanese miniatures, nurtured as carefully as bonsai, could be transplanted to other soil. fs the Rea l Japan the same as the Real World? The answer seems to be yes, if the real world includes New York, where Ogata’s first overseas tour, in October 1993, won audience and critical acclaim. Simultaneous English translation, literal and also faithful to the sound, was available on head phones, performed by actor Mark Cote. About a third of the audiences were Japanese (there is an Issey Ogata video circle in Manhattan where expats gather monthly to watch the latest t stuff), but most of the locals knew next to nothing about him. To “situate’· Ogata in an American context, an introduction referred to evolutionary monologists Jerry Lewis. Woody Allen, Robin Williams, and Eric Bogosian.

Tours to Paris and Munich this year will further test the universality of Ogata and Morita’s comedy. If they succeed, it will no doubt involve transforming a contempt for Japanese as social sheep and economic wolves to a sympathy for the underdog. For the New York debut, producer Paula Lawrence of The Japan Society selected pieces which deflate the stereotype of the loyal, workaholic, buttoned-up salaryman cum foot soldier of Japan Inc. Far from exotic, the characters resonated with the Village Voice critic as “citizens of the world of urban neuroses.” They included the subway rider who loses both dignity and sanity in the crush, the bartender eruption with petty cruelties as he flicks his fan at the oppressive heat, the 40-something classical musician who can find no one to replace his dear departed mother, and the businessman at the hostess bar who is alternately obsequious, pained by his ulcer, lecherous and bored. of the notion of tatemae/honne is not well known, the gap between stuffy ideal and pathetic reality is both older and newer than Prufrock. The Voice critic took pleasure in watching salarymen “wriggling on their pins of decorum or unexpectedly, disastrously getting loose.”

In Japan. thanks to careful attention to the questionnaire given out after every show. the Ogata cult has grown to a national network of devotees, many on the mailing list for newsletters and postcards. A video series (15 so far), two published script collections, a photo calendar and collections of short stories have steadily built up Ogata’s reputation, as have his frequent appearances in films and in television programs and commercials. The cameo format highlights Ogata’s mastery of nuance and caricature, blending a strong sense of deja-vu with an instantly appreciable (or detestable) characterization.

Despite the fame and lucre of television, live performances remain central to Ogata’s artistic life. While they continue to create new sketches for Tokyo connoisseurs, Ogata and Morita use regional tours as chances to perform classics. (Ogata recently conquered claustrophobia and began riding the bullet train network.) The most recent pieces reflect Ogata ‘s reactions to New York, including the opening of a grande dame’s exhibition. Who will guess what will happen now that Ogata’s wit has been unleashed.

Jonah Salz is a theatre director, producer, teacher, scholar and translator based in Kyoto. In 2000 he founded Traditional Theater Training (T.T.T.), a three-week summer intensive training program that introduces the traditional arts of Noh, Kyogen, and Nihonbuyo. He is the editor of “A History of Japanese Theatre” published in 2006 by Cambridge University Press. This article by Jonah appeared in issue KJ26, published 1994.

Photos by Makoto Kemmisaki

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013