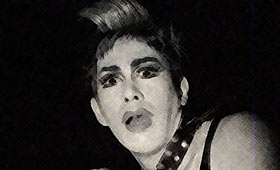

Furuhashi Teiji (1960-1995) was the director and founder of the internationally-acclaimed, Kyoto-based performance group Dumb Type.

[I] started studying painting when I was about five or six, because my father wanted me to. He used to paint Nihonga, that boring old stuff, but I guess he couldn’t make any money doing that, so he became a kimono designer and started his own company. I was more interested in music, because my brother was in a rock band. In junior high and high school I was a drummer in rock bands, and I got to be pretty popular on the Kyoto club scene. Then I became interested in composing, and started learning keyboards and guitar. After high school I of course Kyoto University of the Arts. I wanted to study something special, and I wasn’t interested in being party of the casual life of students at places like Doshisha or Ritsumeikan. In my second year I got into video art, through a course called Planning of the Arts. It included video, photography and film, and was quite unrestricted. My main teacher, Seikine Senosuke, was strongly influenced by the Dada movement and was very avante-garde. The university didn’t really approve of the course, although they had been doing it for ten years. Contemporary art wasn’t well-accepted in Japan then.

[I] started studying painting when I was about five or six, because my father wanted me to. He used to paint Nihonga, that boring old stuff, but I guess he couldn’t make any money doing that, so he became a kimono designer and started his own company. I was more interested in music, because my brother was in a rock band. In junior high and high school I was a drummer in rock bands, and I got to be pretty popular on the Kyoto club scene. Then I became interested in composing, and started learning keyboards and guitar. After high school I of course Kyoto University of the Arts. I wanted to study something special, and I wasn’t interested in being party of the casual life of students at places like Doshisha or Ritsumeikan. In my second year I got into video art, through a course called Planning of the Arts. It included video, photography and film, and was quite unrestricted. My main teacher, Seikine Senosuke, was strongly influenced by the Dada movement and was very avante-garde. The university didn’t really approve of the course, although they had been doing it for ten years. Contemporary art wasn’t well-accepted in Japan then.

While I was a student I won first prize at the Tokyo International Video Biennale in 1985, and the work was also invited to the museum of Modern Art in New York. But I was frustrated because video was still something static. Actually it was in 1984 that I started working with some friends at school who were also frustrated in their own fields. Our idea was to combine everything — film, people, painting, sculpture, music — so it became like theater. We named it Dumb Type because we didn’t want to use any dialogue in our performance. In Japan especially there is too much information, and most theater groups use lots of words. We doubted words were the main form of interpersonal communication, and we wanted to explore deeper levels. We sometimes use quotations from newspaper or a popular song in our performances, but words are never central to the piece.

There wasn’t really any mixed-media theater in Japan when we started. There was a big movement in the ‘60s, including the avant-garde tent theater groups. They were connected to the student movement and kind of hippie-style. They still do it, but it’s completely changed. It’s gone commercial since they no longer have anything to fight against. We wanted to synthesize the visual arts to make something beautiful and unique which would fit the world today. In 1985 I went to New York and saw all kinds of performance art, and I realized that lots of people thought like me. When I saw Einstein on the Beach at the Metropolitan Opera, I thought, “Wow!, Americans are really crazy, doing this at such an establishment place.” After that trip I was pretty sure about what I was doing.

In one of the short segments of my video work that was shown in New York [“Seven Conversation Styles”], I synthesized an image of myself on top of the monkey mountain at the Kyoto Zoo, where there was a lot of communication happening. One reviewer wrote that Japan is such a strict society that the people just want to shout when they are alone, due to a lack of personal communication. I was thinking something like that when I made it.

We performed Pleasure Life, in New York, London, and Germany in 1988, and the people thought it looked really scary. Actually, it had a lot to do with the reality of Tokyo. When we did it in Tokyo, many people thought, “That was fantastic, that was our life in the future and I love that kind of life. Everything is computerized and it looks very pleasurable.” Lots of people said “Pleasure Life” was futuristic, but we were describing Now. The things we used in the performance were all ready-made things we bought off the shelf. So it must be now. There was a political element there, but Japanese audiences don’t want to see that. They want to avoid it. They just want entertainment. Japanese audiences are very lazy.

It’s more difficult to do creative theater in Tokyo than in Kyoto. Here, there is less pressure so we can be more free, more adventurous. Kyoto people are more open to something experimental. For example, when we took “pH” to Spiral in Tokyo, they wanted tickets to cost 5000 yen. I finally talked them down to 4000. They said if the tickets were too cheap, people wouldn’t come! And they insisted that we make the performance “perfect” and totally understandable. It was like providing a service. In Kyoto the tickets were 2500 yen, and I could make changes from one day to the next. I wasn’t sure they would work, but I wanted to try, so we just did it.

We don’t want to live in Tokyo because we’d have to live like Pleasure Life. Those commercial things, the show business idea, are the enemy for us. We want to break it. That’s why we’re doing this. And the younger artists in Tokyo think even more commercial than the rest. They don’t have any political ideas. They just love Japan, and that’s very scary to me.

All of Dumb Type members are “part-time artists.” We have to have other jobs, like most Japanese artists. I compose background music for promotional videos and “fashion buildings.” This work is very stupid, and it’s too bad that I can’t live without doing it. In the Western world artists like me get money from governments and foundations, but there are very few grants in Japan, and they are mainly for traditional artists. I also do TV work. I’ve helped NHK with some special arty programs. I could even say I’ve directed, because they usually have no idea about creating art programs. That’s why they hire someone from outside like me. I did the picture boards and wrote some of the texts. But even though the directors liked my ideas, they couldn’t change much because NHK is such a bureaucracy. The head people think a TV program has to be understandable to everyone from five to sixty years old.

The idea for Diamonds Are Forever parties was born in New York back in ’85. My first night there I went to a disco in drag. Two weeks later a friend and I did a show at New York club. We called ourselves the Kookie Kabuki Sisters, and we did ikebana, sushi and tea ceremony in a very kitschy, Takarazuka style. We were wearing outrageous underwear under our Japanese costumes, and at the end we stripped down. The crowd loved it. When I returned to Japan I found the nightlife really boring. I wanted to put some new life into this uptight society, and fortunately I met Simone Fukayuki, the queen of the Osaka drag queens. We did the first Diamonds Are Forever party last December, with two shows. The Diamonds Are Forever parties in Kyoto and Osaka are getting very popular. We had 1300 people in Osaka for the opening at Paranoia. We don’t make much money, they’re just for fun. I do lipsynch — Julie Andrews, the Three Degrees, Shirley Bassie, Madame Butterfly. Next time I’ll do Vivien Leigh, from Gone with the Wind.

Recently Dumb Type has been trying to represent on stage what this world is really like. “pH” doesn’t have a specific theme because contemporary society doesn’t have a specific theme. We would have to force it and it would be a lie. In this piece there are two metal bars which move back and forth over the performance space. They are independent of each other, computer-controlled. The upper bar moves over the performers’ heads, projecting a lot of slide images on the floor. They’re just bars of light so the performers don’t notice them but they are unconsciously influenced by them, like the mass media. But the audience sits above the stage, so they see both performers and images. The lower bar travels at knee level, so the performers have to jump over it or lie down. They have to be very conscious, because it is dangerous. It is a real power to them. I think daily life in Japan is very comfortable. The images projected by the upper bar makes our lives pleasant and guides us, but we don’t have to be conscious of what is going on. I put in the lower bar because I wanted to express that there is a great power in this world which we usually don’t we notice. We don’t want to see it because it’s an uncomfortable power.

We want the performers to describe human beings and life. In Japanese society, the city is like this architecture and it doesn’t care about these performers. pH is a scientific term, and pH7 is the center, where things are balanced. It’s like heaven, limbo and hell. Japanese society now, especially Tokyo, is like limbo. People think it’s heaven but it’s not. It’s really destructive.

In November we will perform “pH” at the Nagoya Institute of Contemporary At, which is the best art venue in Japan. In 1991 we wil take it to New York, on a tour that will be co-sponsored by the Japan Foundation. In March we are doing it at the Kyoto Municipal Art Museum, right next to the Kyoto Zoo and the monkey mountain — back where I started! I wish I could invite the monkeys into the museum…

![]()

(The fourth, sixth and tenth paragraphs are quotations which appeared in the article “The Future Is Now: Kyoto’s Dumb Type” by Steven Durland in the Summer 1990 issue of High Performance, A Quarterly for the New Arts.)