[A]kebono desu ne, I said, pointing with a forefinger at a patch of grey: dawn. A grunt and a curt nod of affirmation. It was a conversation we had had before. His English was limited to a few words — herro, bye-bye, gullfriend-o — and my Japanese was little better. Still, I wanted to talk about it. Dawn.

Beta, he pronounced, indicating a patch of black, oily beneath a slick of capillary blood. Literally the word meant all over but, in this context, without gradation or, more precisely, an area densely charged with thick sumi ink. Akebono: dawn. Beta: darkness.

Sakura desu, he continued, playing the naming game appreciated alike by small children and adults with limited vocabulary. He pointed at a cuneiform motif in brilliant vermilion with a saffron center and foils of beetle green. Cherry blossom: fragile, evanescent. Sakura, sakura, sakura, he repeated, pointing at a succession of blossoms, some partially obscured by clouds of grey and black.

Sakura wa kirei desu ne, I ventured, and the tattoo master laughed. It was a good-natured laugh. He understood the difficulties of language, and he understood that I wanted to talk about it. It was my skin, after all. It was my life: interludes of color between the darkness and the dawn.

[Y]ears before, I had become entranced with irezumi, more elegantly known as hori-mono, the Japanese tattoo. Yet I had known, from its first vague awakening, that my interest somehow lay deeper than my skin. Then, as now, the result was of little consequence to me. Rather, I sensed that in essence a Japanese tattoo was more than a picture. It was a decision, an act of existential willfulness, not only unnecessary, but ill-advised, an act the effects of which were irreversible, and that to pursue such an action, fully cognizant that pain would be involved, as well as some degree of risk, was nothing short of sublime — a feat of grace. I resolved, one day, to do it. But my resolution entailed certain stipulations: it must be done in the traditional way, and it must be done at the hands of a master of the art. A dozen years passed, during which I experienced no inclination to have myself otherwise tattooed. And then, during an eight-month sojourn in Japan, with some difficulty — for in Japan tattoo is, as it has always been, a mysterious and clandestine art — I contacted an irezumi master.

[Y]ears before, I had become entranced with irezumi, more elegantly known as hori-mono, the Japanese tattoo. Yet I had known, from its first vague awakening, that my interest somehow lay deeper than my skin. Then, as now, the result was of little consequence to me. Rather, I sensed that in essence a Japanese tattoo was more than a picture. It was a decision, an act of existential willfulness, not only unnecessary, but ill-advised, an act the effects of which were irreversible, and that to pursue such an action, fully cognizant that pain would be involved, as well as some degree of risk, was nothing short of sublime — a feat of grace. I resolved, one day, to do it. But my resolution entailed certain stipulations: it must be done in the traditional way, and it must be done at the hands of a master of the art. A dozen years passed, during which I experienced no inclination to have myself otherwise tattooed. And then, during an eight-month sojourn in Japan, with some difficulty — for in Japan tattoo is, as it has always been, a mysterious and clandestine art — I contacted an irezumi master.

Our first meeting was a preliminary that precedes every compact between a master and his client. The master evaluates the client’s sincerity and character in much the same way that the client evaluates the master’s style and virtuosity, for the master believes that once he has put needle to flesh, not only does the client become the bearer of his design, but of his honor, as well, and an earnest master will not commit either his skill or his reputation to one he deems unworthy of its custody.

Tea was brought. Meishi (the ubiquitous business cards) were exchanged. Polite questions were asked regarding family, credentials, and status. Akasaka, whose working name signifies an ascending path, exhibiting mild amusement at the notion that a gaijin should want traditional tattoo, made jokes at my expense that, innocuous though they were, nevertheless caused faint blushes among the several apprentices who had gathered around. I presumed I was only being tested which, perhaps, was itself the objective of the test, and therefore remained composed. Form.

All the while Akasaka worked kiku, chrysanthemum flowers, upon the shoulder of a young man who ground his teeth and clenched his fists against the mat on which he lay. Our eyes did not meet, except as they were locked upon this common object of our attention, the tattoo revealing itself in a blossom of blood from beneath the skin of that young man. Then, suddenly, Akasaka looked up and spoke to me directly. An apprentice translated for my benefit: Teacher Akasaka say he think he can make tattoo that will be please to you.

[I] had settled into a tidy four and a half tatami room in Minato-ku, a few blocks from Tamachi Station. The elevated Shuto Expressway ran past the front of my grimy apartment block and, in the rear, a salt-water canal flowed by beneath my window, home to egrets, cormorants, crabs, and square-shouldered, bob-tailed alley cats. An arching bridge spanned the canal to the north, across which working men marched toward the docks each morning in a silver light, reminding me fancifully, if unoriginally, of Hiroshige. Noodle-sucking Japanese inhaled their breakfasts in noodle stands along this path, and gangs of workmen, uniformly dressed in khaki, with white plastic helmets and close fitting jika-tabi, split-toed canvas work boots, performed calisthenics to amplified plink-plonk Romper Room ditties. Grave, grey-clad schoolgirls made their way toward a nearby private high school and blue-suited salarymen and prim office women strode to their office buildings. Ambling in the direction of the train station, an outlandish round-eyed head bobbing like a beachball upon a sea of raven-haired congruity, I daily breasted this purposeful crowd and left it astonished in my wake.

One day, wandering among houses with arching tiled roofs and gardens of bonsai delicacy, a striding monster breathing smoke confronted me. Not Godzilla, but a fifty-foot billboard of the Marlboro man. In the summer of 1995 Waterworld, the time that land forgot, was big in Tokyo. Kevin Costner, exuding fair-haired American charm, appeared on talk shows ad nauseam. But, by far the most insistent, the most gleaming, the most awesome star writ large by Japanese television in the summer of ’95, the fiftieth anniversary of the leveling of Nagasaki and Hiroshima with atomic bombs, was Enola Gay, the B-29 that delivered them, demonstrating once and for all that, in Japan, America was larger than life — that, in Japan, America somehow loomed larger than death itself. Was it love, or was it mere fixation, the unwitting daydream of a Freudian aspiration?

At first I found it hard to reconcile this improbable crush. At that time I considered the America I lived in to be cynical, self-indulgent, and derivative. Yet, as I grew to know Japan (however imperfectly), I realized that what Japan found irresistible about America was not different in principle from that which my own naive blue eye, in its unblinking optimism, had found irresistible about Japan. Thus, even as Japan, like a besmitten teenager, pursues the buxom fantasy of its American sweetheart, a romance of furtive gropes and fumbling, so its sophomoric advances are awkwardly returned, as when an American friend, enamored of the Land of the Rising Sun, had a pair of geta, wooden platform sandals, custom made for his size thirteen feet, in which he looked like nothing so much as a man standing on a matched set of small coffee tables.

[T]he evening of my first appointment with Akasaka, I took the Keihin-Tohoku rail line to the outlying suburb where he kept his studio. Arriving early in order not to be late, I sat outside on the street corner to await the precise moment for a timely appearance since, in Japan, timeliness is important, and premature arrival is as indefensible as tardiness. The neon lights of love hotels winked and hummed beneath a harvest moon, and black bicycles rattled by, uniformed high school girls standing erect in slouching knee sox and loafers upon the rear hubs, hair and skirts flying. Their small, white hands lay like smudges of powder beside the high tunic collars of their lean, furiously pedaling boyfriends.

At exactly seven o’clock I entered the small studio through a discreet door. Several apprentices and their clients acknowledged my sudden appearance with alarmed expressions, a common greeting for foreigners who materialize in places where foreigners are never seen. One wonders if one has inadvertently trespassed, a thought shared by both parties. The senior apprentice, a man tattooed from his neck to the koi that swam upon the tops of his feet, rose hastily and disappeared up a narrow flight of stairs. I waited until he reappeared, beckoning me with a fluttering of the fingers that in the West means ‘shoo’.

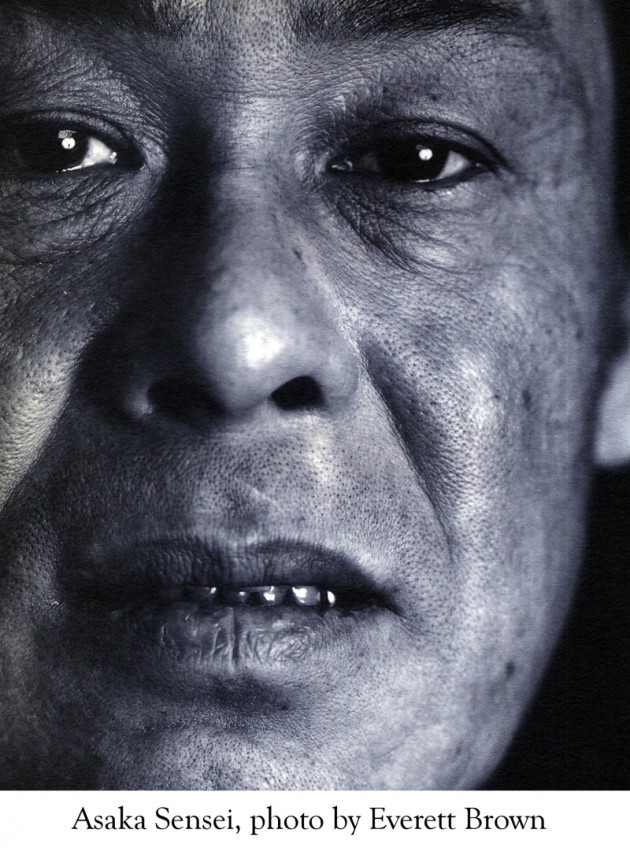

Akasaka was seated on the floor soldering together bundles of needles. As it happened, Akasaka-sensei was one of the most venerated tattoo masters in Japan, twice world champion. I did not know this when I had first sought him out. I had merely seen a picture of him and had been impressed by his sober demeanor. At forty-four, I would have guessed his age to be fifty-four. He was unbendingly dedicated to his art. He was a hopeless English student. There was no vestige of piety about him, a man of the world who loved enka, the proletarian soul music of Japan, luxury automobiles, girls, all the simple pleasures of the flesh. He ate o-bento from the convenience market, smoked and drank. Yet when once I asked him about a photograph in his studio of a man silhouetted against the backdrop of the Taj Mahal, he pointed at his own nose and told me about having visited. Finding the paving stones strewn with leaves and dust, he had asked for a broom and had swept them himself in the fast belief that a monument of such age and distinction should be tidy.

I bowed.

He dipped his head and shoulders, returning to his work while I removed my shoes and coat and sat down on the zabuton that the apprentice had positioned, just so.

O-cha, green tea, was served. I waited.

The apprentice kneeled beside the master.

We waited.

At length, Akasaka made a noise in his throat, a sort of uhn that means… I do not know what it means, but in Japan it is ubiquitous and addictive and I, myself, still fall into the habit of it from time to time. He looked up and a smile divided his face. He nodded and gestured toward the mat laid out on the floor before him. I removed my shirt and positioned myself in front of him so that my knees touched his knees. He drew deeply on a cigarette (Hope brand), from a packet placed and perpetually replaced within reach by his attendant), tilted his head, and squinted through the smoke at my chest and shoulders. Then, with the tip of a sumi brush, he drew the first strokes of his design upon my skin. And I realized that thereafter nothing in my life would be quite the same.

[I]t is usual for the irezumi master and his client to negotiate the iconography of the tattoo. This is in part a matter of aesthetics, design, and in part a question of signification, for the tattoo must mean something, must say something profound about the person upon whose skin it is inscribed. Japanese tattoo is an unforgiving medium that does not make allowances for duplicity or self-deception. The tattoo is, after all, not an investiture that can be sloughed off like a business suit, a uniform, some hip ensemble. It is as real as flesh. It is the very skin of truth. I had selected a classical motif called sakura-hubuki, literally “cherry blossom storm”. At Akasaka’s behest we added ryu, the Japanese dragon, accompanied, as always, by taifu, typhoon, the divine wind. In the Japanese arts, cherry blossoms, which survive in splendor for a day or two only before being blown to the ground, symbolize the transitory nature of life. Ryu, a water motif related to the naga of Southeast Asia, and invested in the ancient cosmologies of Hinduism and Buddhism alike, symbolizes the force that compels being and nothingness to issue one from the other. To my mind, the dragon is neither good nor evil, neither dark nor light, but is responsible for the tendency of all things simply to be or not be. Dragon and typhoon, cherry blossom and storm. Being and nothingness, and that which arouses them to issue one from the other. It was an elementary dichotomy, yet for me a symmetrical one that fit with equal aplomb the analogous nature of my mind and the reflective congruity of my body, the right side and the left side which, meeting, comprised the center.

Traditional Japanese tattoo is executed following a bipartite process. The outline is inked in first. It may be drawn using an electric needle (the single, electrically-driven needle is utilized only as a time- and cost-saving device, and while it is not scorned by the master, apprentices — in the way of students — will occasionally speak of one-point, or American style, tattoo with thinly masked derision), but if it is incised in the traditional way, it is done with no more than two or three hari, needles, bound together and mounted in a wooden grip. The coloring of the design comes later, one hue at a time — more or less, as the tattoo master usually works areas of the design defined by the contingencies of time: the length of the appointment, the depths of the client’s pocketbook, the limits of the client’s capacity for pain. Coloring is considered to be the most important part of the work, and is strictly the domain of the master. Indeed, if any part of the tattoo is colored by anyone other than him, the master will disavow it.

Broad areas of color are charged with as many as ten needles mounted together in a wooden handle. The master spreads the skin of the area to be colored between his thumb and forefinger. The wooden handle rests across the thumb and is worked by the other hand in prodding strokes. Each stroke pushes the inked tips of the needles into the lower epidermis rapidly and accurately. Lighter tones are effected with a shallow infusion and a sparse pattern, while intense color is injected deeply, in a dense pattern. One learns to associate luxuriance with the sharply rising curve of pain, and with the alarming rhythmic sound, not unlike velcro being pulled apart, of ripping flesh.

Pain is the cornerstone, the mystical heart, of traditional Japanese tattoo. Another name by which tattoo is colloquially known in Japan is gaman, meaning patience, and a word one often hears softly spoken in the course of tattoo work is ganbaru: bear it. An American scholar of Japanese culture, who had written a book about irezumi, once asked me to describe the pain involved in Japanese tattoo for, in spite of his close affiliation, none of his Japanese correspondents had been willing to talk about it. Form, a sort of unspoken code of honor, prohibits those initiated into the mysteries of Japanese tattoo from admitting to the pain involved. The client who never flinches, who never grimaces or grits his teeth, will win the master’s heartfelt respect. Of course, such forbearance is sometimes nothing more than macho posturing but, given the depth of the pain, one can only sustain one’s disingenuousness for a relatively short period of time. The person who genuinely seeks to take possession of his pain steps forth boldly to meet it and, having done so, discovers that it is less frightening than he had expected. It is a relative condition, not unlike pleasure, though at the opposite end of the scale that can be experienced with or without tolerance lightly or profoundly, hedonistically or profitably, depending upon the focus of one’s attention. The experience of pain, but one of the body’s many ecstasies, is ironically the truly enduring mark of traditional Japanese tattoo, for it becomes engraved upon the soul, just as pictures are engraved upon the flesh, and the deeper memory of it relentlessly wakes the bearer from his unrepentant slumbers, reminding him, and often him alone, to know all the moments of his brief existence.

Japanese tattoo was conceived in shadow, and it abides in shadow today. Yet, in the course of its long and obscure history, it flourished. It is one of Japan’s high arts and is widely recognized by the rest of the world as the pinnacle of the craft, though it has been disowned in its native land. Its vague early history consisted in a nebulous medley of poignant marks that little resembled the complex, decorative designs of the art in its maturity. There were tattoos that identified criminals. There were tattoos assumed as indelible pledges of love, the beloved’s name inscribed upon the flesh of the lover with the ideograph for inochi, life. There were tattoos that inveighed religious piety. There were tattoos that rendered marginalism precise.

The decorative pictorial tattoo evolved gradually during the Edo period, hand in hand with ukiyo-e, the popular woodblock print. Some of the great masters of ukiyo-e were also tattoo designers, and their iconographies and sense of style survive to this day in the designs of Japan’s traditional tattoo artisans. Even the gestures inherent in the creation of traditional tattoo are remarkably similar to those of the woodblock designer and carver, and the word hori, itself, from which the name hori-mono is derived, articulates the motion of digging or gouging or carving.

[T]he most assertive single influence upon the development of the decorative tattoo in Japan was the translation and publication, in the middle of the 18th century, of the classic Chinese novel, Shui-hu Chuan (in Japanese, Suikoden), variously rendered into English as The Water Margin and All Men Are Brothers. This hugely popular work recounted the exploits of Sung Chiang and his rebel companions during the years 1117 to 1121. Outlaws and brigands, they nevertheless were men of honor, and each section of the book tells of one man’s exploits in revolt against a corrupt government. Significantly, a number of these champions were tattooed, and were so depicted in accompanying illustrations by Hokusai, and later by Kuniyoshi, in the Japanese editions. What is historically incongruous, yet noteworthy, about this novel was its overwhelming popularity during the reign of the Tokugawas, a regime whose indelible totalitarian mark upon the Japanese people is undeniable to this day. It is an epic rife with personality and rebellion, and its favor bears witness to the alter ego, albeit reserved, of a people whose extraordinary passion would, and will, not be snuffed by the blank hand of bureaucracy, even when that hand is its own.

The proletarian classes of Edo embraced the virtues of Sung Chiang, virility, honor, and self-determination. The full body tattoo provided this circle of working men, in ostentatious imitation of their heroes, with a means of subsuming values they admired while, at the same time, and in an explicitly Japanese way, pledging their nakama, their insiders’ clique, all members of which would bear similar tattoos. Predictably, it was not only honest working men who found the qualities attributed to Sung Chiang and his band of outlaws appealing.

In Akasaka’s studio I often encountered formal Japanese wearing — or at those moments not-wearing — clothing of questionable taste, with full body tattoos in various stages of completion, who revealed not (except in their too perfect concealment of it) the slightest surprise at the appearance of a tattooed foreigner among them, maintaining a prim indifference and never speaking to me directly, yet with respect to whom Akasaka would archly say, gangsta’, cocked forefinger pointing at my chest like the barrel of a gun, upon their departure. Akasaka’s connection with yakuza, the Japanese underworld, was given, though unspecified. In Japan, the traditional tattoo is the mark of a gangster, and Akasaka’s position in the guild made an alliance inevitable. That he was, himself, a ‘gangsta’ seemed entirely unlikely. Nevertheless, he commanded perfect obedience and loyalty of his students, a pervasive, if archaic, Japanese ethic that is ardently revered but is nevertheless comparatively ephemeral in modern Japan outside the strictures of such conservative nakama as the yakuza. One of Akasaka’s apprentices, a young man from Kobe, even wore the tattooed kanji characters for Akasaka family member in a prominent line down his belly.

Centuries ago, criminals were tattooed beneath the arm, and the decorative tattoo, according to legend (although not necessarily in accordance with historical fact), evolved as a means of concealing such marks within the depths of its fantastic iconography, the decoration absorbing the aberration as the criminal vainly hoped he would himself be reabsorbed into the dense enigma of his culture. It is supposed that the convention of leaving the underarm unmarked proves that the bearer of traditional tattoo is not a criminal. In modern Japan, however, the traditional tattoo no longer conceals, but is itself concealed, and it is virtually impossible for the post-War generation to dismiss the stigma of tattoo from its consciousness. Even I, a henna-gaijin (crazy foreigner), of whom virtually all transgressions were forgiven — and in Japan the number of possible transgressions that one may wittingly or unwittingly commit are uncountable — with great sadness lost several friends to their prejudice.

The fear and loathing that most Japanese adults feel toward irezumi is more than simple prudery. Traditional tattoo provokes a resonant abhorrence (and concomitant titillation — historical books on irezumi, for example, are consigned to the back rooms of Japanese porno emporia) in Japan. It is like the mark of Cain, only relatively more serious. The yakuza correlation was cited by every Japanese person I asked as the reason they believed tattoo was morally wrong. I accepted this, though it was, I felt, at once the root and far from the root of the issue. The root itself, in the nature of roots, diverges interminably. One must ask why and why and why again. Why does the association of tattoo with the underworld make tattoo bad? Because the underworld is frightening. It is unpredictable. But most people who have borne traditional tattoo throughout its long history have not been affiliated with the criminal element. Even today tattooed people are not necessarily lawbreakers. Why are these tattooed people bad? Because they are different. They have set themselves apart. Is this wrong? Is it not their choice to do with their body what they will? No, it is not their choice, because their body does not belong to them. A person’s flesh is indistinguishable from the flesh of his parents, or of his parents’ parents. By indelibly tattooing the flesh of one’s body, one sets apart, and thus dishonors, the flesh of one’s ancestors.

[I]n 1996 I returned to Tokyo to do some work for a major museum, work that occupied my days with the same frantic (but nevertheless regulated) precariousness that propels Japanese people headlong down the corridors of their lives. I filled the nights with appointments at Akasaka’s small studio. After two weeks, on the evening before my departure, I arrived at the studio for a final visit. Akasaka’s apprentices were seated downstairs, and we exchanged greetings. I sat down in my coat and looked meaningfully in the direction of the senior apprentice. The formalities had been dealt with and I was ready, if not a bit impatient. But he avoided my glance and uncomfortably lit another cigarette. What’s all this, then? I thought to myself.

Eventually he rose from his seat and ascended the stairs, soon to return. Teacher Akasaka had confirmed that there would be no appointment that evening. Betraying no emotion, I replied, ah, so desu-ka. Not an insistent why, the plaintive demand of a Westerner, but more politely: oh, is that so. The other apprentices had fallen silent. Nervously, the senior apprentice explained to me that Akasaka-sensei had decided he would like me to accompany him, as his guest, to an onsen, a natural hot spring, at a resort in the mountains north of Tokyo.

Fully aware that tattooed men were banned from public baths in Japan (the international pictograph for “no tattoos allowed”, decorated limbs with a canceling diagonal slash, is prominently displayed), I realized that this would be a special onsen and that its patrons would therefore, on this occasion, undoubtedly all be tattooed. I was stunned. I was, after all, gaijin, a foreigner, an outsider, and the nakama of men bearing traditional tattoo was so private, for obvious reasons, as to be virtually invisible. Surely Akasaka was joking?

No, we would leave in half an hour.

We took one of Akasaka’s plush vans, detouring to pick up my belongings, as we would spend the night at the resort, from which I would be driven the four and a half hours back to Narita Airport in the morning. The young apprentice from Kobe was my chauffeur. He demonstrated for me the van’s satellite navigation system, and then we talked until conversation had exhausted itself (and me). Eternally solicitous of my needs, real or imagined, he then switched on the miniature television set mounted to a swiveling bracket beside the steering wheel, and commenced a running commentary of the game show to which it was tuned, while I quietly dozed off.

Having stopped only for a quick meal at a roadside tonkatsu-ya, we arrived at the onsen at about eleven o’clock. Akasaka and several of his younger apprentices including, unusually, a young woman who was presumably also his mistress — a different one from the girl I had met the year before — were just arriving. To my great happiness, Akasaka had brought his kit with him and proposed that we accomplish some tattoo work before partaking of the hot springs. We arranged ourselves on the tatami mats in my room, switched on the TV, unpacked the beer, and were soon riding high upon waves of cross-cultural hilarity. Outside the somber confines of the studio, it was the young peoples’ opportunity to let their hair down a little, and they asked frank questions about my person and my profession. My judicious answers only provoked further and more candid lines of inquiry, and soon they were scrutinizing the snapshots of girlfriends in my notebook and pressing me for details concerning my love life. Akasaka worked industriously on my tattoo. He had asked me what part I would like him to finish that night, and when I had chosen the dragon, he had nodded his approval.

Eventually, cued by a glance from his teacher that did not escape my notice, one of the apprentices asked, how long can you stay? Momentarily confused by his ambiguous English, I hesitated, and as I did so I saw the young man’s brow furrow and his eyes flicker in the direction of his master’s face. In that instant the subtext of his question became clear to me: Akasaka was fatigued, but good manners forbade him from saying so. I’m tired, I said, can we stop now? An audible sigh made a circuit of the room, and we all smiled.

A tattoo appointment is always properly followed by a hot bath, the pangs of which are exquisite. In addition, the steaming bath is the best venue for seeing tattoo, as well as for being seen, since the skin’s surface dryness is quenched and the heat produces a flush that intensifies the colors and, as the blood rises, transfuses and enlivens them. Gathering in the large tub, we examined each other without pretense, appraisingly. I was surprised to discover that Akasaka, himself, was only sparsely tattooed, and that his calves, like those of his apprentices, were a cacophony of random marks, mere scribble boards for testing colors and experimental configurations. The only woman among us, Akasaka’s student mistress, also tattooed (but whose tattoos we would have to scrutinize in imagination only), called to us over the wall that divided the men’s bath from the women’s side, making the boys laugh and fidget with unrequited emotion.

Then, because it was seemly and decorous, and also because it simply pleased him to amuse himself in this way, Akasaka instructed his youngest disciple to wash me. As we stepped from the bath and I seated myself on a low plastic stool beside the faucets, the poor boy’s discomfiture provoked roars of laughter from the others who, undoubtedly, had themselves been subjected to similar mortifications. All I could do to save him was to maintain a straight face and allow him to proceed. With a pleading look in his eyes, he pointed questioningly in turn to my arm, my leg, my back, chest, stomach, and from his perch on the edge of the great, steaming tub, his master invariably acknowledged his inquiries with single firm nods. I have, I must admit, never been so intimately soaped up and scrubbed down by a young Japanese boy.

I had been honored, but was still, as I had been from the beginning and would ever be, the object of Akasaka’s harmless little jokes. Yet, some nights before, as I had lain on the familiar mat in his studio, I had allowed my eyes to examine, object by object, the trappings of the room. All the larger accouterments, the samurai armor, the swords, the Buddhist saints and deities, all the knickknacks, the equipment, the small toys, were in their places. The nattily framed photographs on the wall, all were familiar from the previous year, but one. During a break I walked over to examine it more closely. In it Akasaka bent over a recumbent form, working assiduously. The outline of the client was both familiar and unfamiliar to me, but I recognized the tattoo’s motif. Sakura-hubuki. Cherry blossoms, some obscured by clouds of grey and black.