Catherine Ludvik

The history of the pilgrimage is traced back to the monk Kūkai 空海 (774–835), a native of Shikoku, from the province of Sanuki (Kagawa), who established the Shingon sect of Buddhism in Japan.[3] Posthumously known as Kōbō Daishi, among devout pilgrims he is called “Odaishisan” お大師さん, and figures prominently in legends and miracle stories. Numerous sites around the island, including the 88 temples, are associated both with the historical Kūkai and even more so with his deified counterpart, the legendary Kōbō Daishi of popular faith.

Simultaneously at different levels, Kōbō Daishi is ever-present in the pilgrimage: in addition to being worshipped at the official “88” and many other temples, roadside shrines, and small statues of him along the way, he himself is also believed to be continuously circumambulating the island, and is furthermore represented by the pilgrim’s staff (kongō-tsue 金剛杖), providing each individual with physical and spiritual support, protection, and guidance. As a material embodiment of Kōbō Daishi and as the pilgrim’s very own, personal Kōbō Daishi, the staff is an object of particular reverence for the devout. Through it, they continuously keep company with him, as expressed in the well-known phrase dōgyō ninin 同行二人: fellow travelers on a physical and, above all, spiritual journey, wherein the two participants (二人), the pilgrim and Kōbō Daishi, engage in the common practice (同行) of performing pilgrimage. The central concept of dōgyō ninin is further reinforced through the inscription of the characters on the staff and on other pilgrimage items.

The Heart Sutra, which is recited at every temple and hand-written copies of which are offered by especially dedicated pilgrims at each of the 88 temples, is also inscribed on some staffs. In fact, there are some pilgrims who make their own staff and write out the sutra on it. Thereby they undergo spiritual preparation before their pilgrimage by further personalizing their relationship with Kōbō Daishi and, in the process, lending another layer of depth to their devotion to him. The staff is therefore also a product, an embodiment, and a witness of their faith, which transforms a walking stick into a pilgrim staff. While the staff may identify a person as a pilgrim, it is actually the pilgrim who through his devotion brings to life the symbolic potential of the staff. During the pilgrimage, at the end of each day, devout pilgrims clean the bottom of their staff, as if washing Kōbō Daishi’s own feet. And since the top of the staff, on which is placed an embroidered cover with an attached bell, would represent Odaishisan’s head, out of respect the occasional pilgrim will not grasp that topmost part as a handle, but rather hold the staff at a lower point. A literal reading of the symbolism of the staff thereby transforms it, in the eyes of the devout, into an actual image of Kōbō Daishi. With long-time use, the precious staff grows shorter, but even after it has outlived its practical use, some may be unwilling to part with it. We once met a schoolteacher from Hokkaidō on his 10th circumambulation of the 88 temples, who carried a very large backpack, but no staff: when we arrived at the next temple, however, his staff emerged from his pack, exceedingly shortened from thousands of kilometers of service and cracked in the middle. No longer a functional object, it had become a pure expression of his devotion and gratitude to Kōbō Daishi, which he carried with reverence. Having ceased to exist as a walking stick—and having always been much more than just that—it embodied his profound sense of the very real presence of Kōbō Daishi in his spiritual journeys, and encapsulated the memory of the joys and sorrows, and trials and tribulations of his repeated pilgrimages.

When my mother fractured her knee last year, in addition to other challenges, and arrived in Japan three weeks later with a brace on it, it became clear that Kōbō Daishi would have to be on double-duty if she would have any chance of walking Henro trails the following month. Her pilgrimage staff took the form of two new, smart-looking hiking sticks, and invoking Kōbō Daishi’s blessings for our dōgyō sannin (three of us journeying together), we set out. Miraculously we walked up and down mountains, reciting Namu Daishi Henjō Kongō 南無大師遍照金剛 (invocation of Kōbō Daishi),[5] keenly aware of the blessing of being able to walk at all, and especially so on these spectacularly beautiful pilgrim trails.

I must admit, however, to lapses in my own reverence, in having repeatedly forgotten my staff in various places. Sometimes its retrieval required just a few steps back, other times a prolonged jog—which I interpreted as being called back to the temple for further prayers—and once a steep drive up a mountain on a temple’s shuttle to their Okunoin 奥之院 (inner sanctuary). The most memorable recovery of my staff, however, was by an employee of JR Iyo Saijō Station, who upon hearing I had left it behind, unhesitatingly jumped into his car and, to my stunned amazement, drove two train stops to retrieve my staff! Would the railway employee have shown me such unbelievable kindness and urgency in assistance had I forgotten another item, unrelated to the pilgrimage? Kindness, perhaps, but not necessarily urgency: it may well be that the particular swiftness of his response was precisely because it was my pilgrim staff, imbued with such profound significance. After all, without Kōbō Daishi by my side, how could I venture further? Each of these instances, therefore, was indeed a learning experience, both in alertness as well as in awe and gratitude at the astounding degree of kindness and support shown to an absentminded pilgrim.

There are many ways to do the Shikoku Henro. Most Japanese travel in cars and buses, a smaller number are on motorcycles and bicycles, and then there are those who walk, which nowadays includes a growing number of non-Japanese. There are also a few who run the pilgrimage. In Matsuyama we met a Japanese man who had begun his running pilgrimage as a commemoration of his father’s passing, combining the Henro with his passion for marathons. Whenever he had free time from work, he would continue to run, dressed in marathon wear with bilingual signs in front and back identifying him as a Henro runner on his 3rd round at the time (at present, in 2018, he is on his 4th).[6] We actually met him twice that afternoon, at two sequential temples, which was a surprise as our walking pace could be no match for his running. As it turned out, he had detoured to go pay respects at his father’s grave. Reverential running.

For those who work, it can be challenging to find time to go on pilgrimage. For one postman, however, his day-to-day job is performed as pilgrimage: rain, snow or shine, blowing his conch, he delivers mail and offers prayers at temples and shrines on his route. We first caught a glimpse of him on a very snowy morning near Yokomineji (no. 60), as he sped by us in his red postal van. The road up to the mountain temple was closed due to snow and ice—which obviously did not apply to the postman—so the only way up for pilgrims was by foot, and indeed small numbers, dwarfed by the immensity of the white-blanketed landscape, emerged from the snow to offer prayers at Yokomineji, and then again disappeared down mountain paths. With the temple grounds wrapped in the deep quietude of the snow, we walked still further up, as we always do, to their Okunoin: from there, Shikoku’s tallest peak, sacred Mt. Ishizuchi (1982m), site of Shugendō mountain asceticism, can be seen and worshipped at a distance, and also approached through a Henro path from here leading to its peak. Another stop on the conch-blowing postman’s delivery route is Ishizuchisan’s large Jōjusha shrine (1450m), where we actually met him the next day.

To deliver mail to Jōjusha is no small matter: everyday the postman takes the ropeway to Jōju Station at 1300m, and then climbs about half an hour up to the shrine, all the while blowing his conch. On the way, he passes Okumaegamiji, the Okunoin of Henro temple no. 64, Maegamiji, located in the foothills of Ishizuchisan. Knee-high in snow on a quickly rising path, as was the case the day we were there, it was not an easy hike—and we were carrying neither a large conch nor the shrine’s mail! At Jōjusha, when we heard the sound of the conch, we assumed a yamabushi mountain ascetic was ascending Ishizuchisan, and what a surprise it was to see a postman! Prayers offered and mail delivered, together we took the ropeway down, and then he speeded off to another temple for more conch-blowing, prayerful post delivery. We had the good fortune to run into him again this year at Yokomineji, this time in light rain that turned the misty mountain scenery into Hasegawa Tōhaku-esque pine-tree forests, filled with mystery and divine presence. As we descended along the Henro path, even from a distance we continued hearing the heartwarming sound of his conch. In fact, as we walked I realized that we had heard his conch-blowing at Yokomineji already years ago, without realizing it was him.

In all seasons, in the snow, in the rain, and in the sun, the mountains and seascapes on the Shikoku Henro inspire awe and reverence. The pilgrimage has given rise to much poetry, as we see in the recent Haiku Path (haiku no shōkei 俳 句の小径) of Kiki in southern Tokushima Prefecture, on a slope above the sea:

静かなる浜に波と鈴の音

On the quietened beach, the sound of waves and of the [pilgrim’s] bell

—Tanabe Keiji 田辺恵司 from Tokyo

空海と紅葉を愛てる二人旅

Cherishing Kūkai and the autumn colors, travelling as two

—Nagao 長尾 from Anan City, Tokushima Pref.

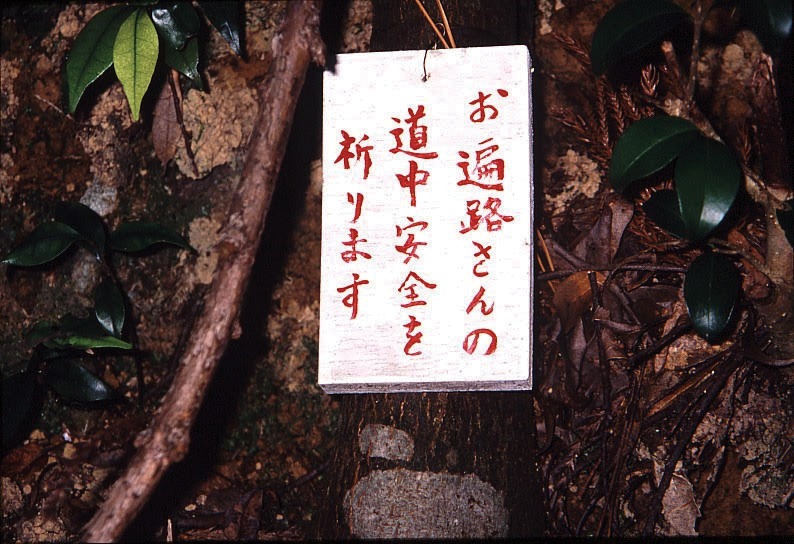

Walking in nature fills the body with clean air, purifies the mind, and uplifts the heart. In the mountainous areas, besides Henro markers on the way, from the trees hang messages of encouragement and words for contemplation, especially on the longer stretches up and down forested paths: “please do your best” (ganbatte kudasai がんばってください); “both in life and on the Henro pilgrimage there are mountains and valleys” (jinsei mo ohenro mo yama ari tani ari 人生も お遍路も山あり谷 あり); “attaining Buddha[hood] in this body” (sokushin jōbutsu 即身成 仏). The outward, physical journey on the Henro path is a reflection of the inward spiritual pilgrimage through sacred space, most intimately recognized as such in the awesome beauty and silence of nature: this is the pilgrimage between the temples. Two years ago we met an American pilgrim at Iwayaji (no. 45), another among our favorite temples, who would be so moved by the beauty of nature on the Henro paths that he would weep at the sight. Iwayaji itself is perched high against a rocky mountain with caves and treacherous peaks as sites of ascetic practice and worship. For walking pilgrims the main halls are descended to from an extraordinarily beautiful mountain path via the temple’s isolated Okunoin, where Kōbō Daishi himself is said to have engaged in spiritual practices. On our very first pilgrimage, we happened to reach the entrance to this Okunoin (known as Seriwari zenjō Hakusan gyōba) just as a group of hardy and utterly fearless silver-aged Japanese pilgrims were unlocking the gate with the temple key. They invited us to join them in crossing the threshold into this mysterious, normally closed away world, in which faith is wedded to the rugged beauty of nature in the veneration of mountains (sangaku shinkō 山岳信仰). We instantly dropped our belongings outside the gate, like worldly attachments for which there is no space on this part of the journey, and eagerly accepted this unexpected blessing, with absolutely no idea of what was to come. First we all climbed up a long narrow crevice between two cliffs, whence comes the name seriwari zenjō 逼割禅定 “crevice meditation,” as both the arresting form of the cliffs’ natural features and the sheer difficulty of the ascent necessarily command single-minded concentration. Then, holding on to chains, we scaled up another near vertical stone surface devoid of almost any foothold, and finally we walked up a dizzyingly high ladder leaning against another cliff. At the top was a small shrine to the mountain deity Hakusan Gongen (hence the name Hakusan 白山 gyōba 行場 “practice site”), around which we all crouched, holding on tightly to a metal rim, and most earnestly chanted the Heart Sutra.

As reverence is practiced, reverence is taught. Indeed we might say this of our own experience at Iwayaji’s Okunoin under the guidance of our devoted white-clad pilgrim group, to whom we are deeply grateful. One can also often witness this, especially on weekends and holidays, when families with young children come to the temples. Most are in cars, but some are on foot, occasionally traversing considerable distances. Many years ago we met a Pure Land sect (Jōdoshū) priest and his wife from Hokkaidō accompanied by their two young grandchildren: remarkably, they were walking the challenging but beautiful stretch up and down three mountains between temples no. 11 (Fujiidera) and 12 (Shōsanji) in straw sandals.

As the families go on pilgrimage together, whether or not in pilgrim wear, the tradition of performing pilgrimage, of lighting candles and incense, of reciting the Heart Sutra and so on are passed on to the next generation, in whom memories of the Shikoku Henro take form. We have sometimes seen children taking particular delight in these family pilgrimages, rushing forward to ring the temple bell, to light the incense and candles, and to bow at each of the temple halls. Some of the parents are particularly intent on having their children not only perform the prescribed actions, no matter how enthusiastically, but actually to learn the recitations. During the Golden Week holiday this year, in Tokushima we saw a family whose little boy of perhaps 5 years old was being taught the Sanskrit derived, sometimes rather complex invocation mantras for the Buddhas and other figures of the Buddhist pantheon enshrined in the temple halls: his mother would say it, and he would repeat it until he got it right. Some two years earlier at temple no. 44, Daihōji, we had met another boy aged 5 on pilgrimage with his father: to our total amazement, this child in immaculate pilgrim wear could chant from memory the Heart Sutra and invocatory mantras! Still more remarkably, he was not an isolated case. Years earlier at temple no. 7, Jūrakuji, we were astounded to notice a family whose children also knew the sutra by heart. Likewise at temple no. 36, Shōryūji, we had run into a grandmother and her 7-year-old granddaughter who had the ability to chant the Heart Sutra loudly and impressively well! These and other examples we have encountered are reminiscent of the famous “tiny tot pilgrim” (chibikko ohenrosan) Yokkun Sensei, who in 1997 at age 3 had begun Henro pilgrimages with his grandmother, quickly learning the Heart Sutra and mantras, and by age 15 had completed 25 rounds! [7]

Children are also taught the age-old tradition of charitable giving (osettai お 接待).[8] Sometimes parents instruct their little ones to give us candy or a cookie, and other times it can take the form of a more elaborately prepared class activity, as we witnessed a few years ago at temple no. 18 Onzanji. Having set up seats and a table for pilgrims to take rest, primary school children served us juice and a snack, and also gave each of us a package, including candies and a personal letter handwritten by each child! A tradition learned in this way, as we discovered, may then become a tradition applied. At the end of one of our pilgrimages, as we were waiting to catch the train at a small station in Tokushima, a junior high school student who was also there waiting, suddenly stepped out of the station and came back with two PET bottles of tea he had purchased for us from a vending machine! We could hardly believe that this young boy could show such thoughtfulness to two probably somewhat tired looking pilgrims. To receive osettai from anyone is always a heart-warming experience, but to receive it from a child is more moving than words can express. It is these children who may well one day bring their own little ones on pilgrimage. Traditions are preserved because they are practiced.

Nowadays family pilgrimages may sometimes also include other much-loved members: pets who can also be dressed in pilgrim wear. They are not stand-ins for people, like the okage inu お陰犬 dogs on pilgrimage to Ise in the Edo Period, but rather pilgrimage companions for those travelling by car. Above all we have seen dogs, but last year we also met someone travelling with two cats in pilgrim wear, including small hats. The pets are not left in the car, but accompany their owners to the temple halls and attend the rounds of incense and candle lighting as well as sutra chanting. Having participated in the family’s acts of reverence, perhaps karmic seeds are sown for the pet’s future birth as a pilgrim.

Pilgrimage can be and often is a transformative experience. What then has been transformed on our journeys of reverence over the last twenty-three years? Perhaps it is an increased sense of overwhelming gratitude for the countless awesome experiences of pilgrimages past and present, for the opportunity and tremendous joy of chanting at temple halls, and for the blissful experience of the profound beauty and silence of nature as sacred space. It is also a heightened awareness that reverence in itself is a precious gift, without which the journey would be only a hike.

[1] New York: Morrow, 1983. [2] On the Shikoku Henro pilgrimage, see Ian Reader, Making Pilgrimages: Meaning and Practice in Shikoku (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2005). [3] On Kūkai, see Yoshito S. Hakeda, Kūkai: Major Works Translated, with an Account of His Life and a Study of His Thought (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1972); Ryūichi Abe, The Weaving of Mantra: Kūkai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000). [4] On Kōbō Daishi faith, see Hinonishi Shinjō (ed.) Kōbō Daishi shinkō 弘法大師信仰 (Tokyo: Yuzankaku, 1988). [5] On this mantra invocation, see Hinonishi Shinjō, “The Hōgō (Treasure Name) of Kōbō Daishi and the Development of Beliefs Associated with It” (William Londo transl.), Japanese Religions 27:1 (2002), pp. 5–18. [6] www.shikoku88.jp [7] See John Shultz, “Pilgrim Leadership Rendered in HTML: Bloggers and the Shikoku Henro” in Japanese Religions on the Internet: Innovation, Representation and Authority, eds. Erica Baffelli, Ian Reader and Birgit Staemmler (New York: Routledge, 2011), pp. 110–112. [8] On osettai, see David C. Moreton, “The History of Charitable Giving along the Shikoku Pilgrimage Route,” M.A. Thesis, University of British Columbia, 1995. Available online at www.shikokuhenrotrail.com/shikoku/moretonThesisComplete.pdf

CATHERINE LUDVIK obtained a Ph.D. at the University of Toronto and teaches Japanese religion, visual arts, and culture at the Stanford Program in Kyoto, Doshisha University, and Kyoto Sangyo University. Spanning Indian and Japanese religions and their visual arts, her research interests focus on the metamorphoses of the originally Indian goddess Sarasvatī/Benzaiten in the texts, images and rituals of Japan (see KJ62), as well as on the circumambulating practice (sennichi kaihōgyō) of the monks of Mt. Hiei and the Shikoku Henro pilgrimage.