Marc Peter Keane and Jeffrey Irish

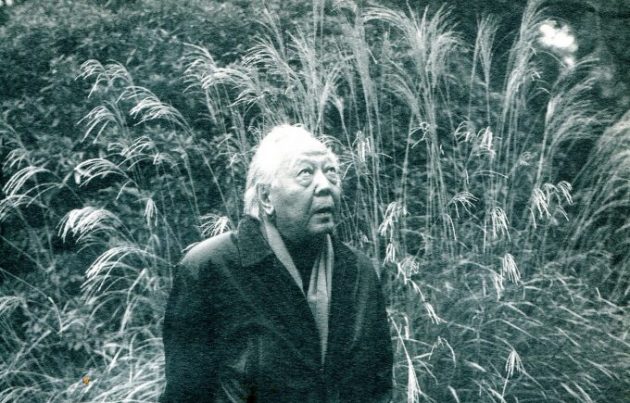

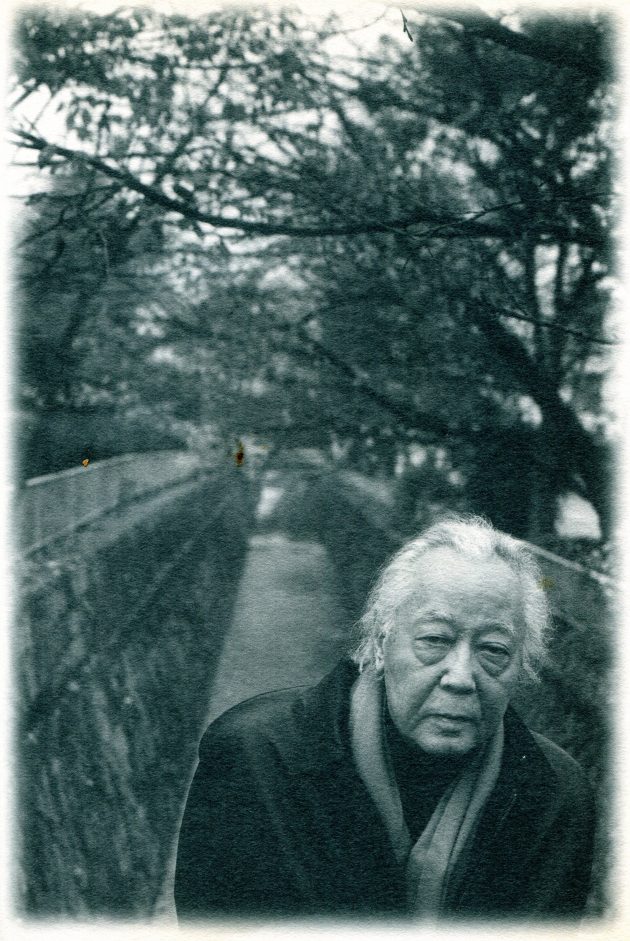

How does one become a citizen of the world while remaining devotedly Japanese? Katō Shuichi, 82, has surely shown the way. Cultural critic, literary historian, novelist, poet and dramatist, Katō is one of Japan’s major post-war figures, a cosmopolitan who illuminates such widely divergent topics as art, religion, literature, society and politics.

Fluent in German, French and English, Katō speaks a unique Japanese peppered with foreign words (in italics below), which rolled like thunder off his lips when he spoke last winter with KJ’s Jeffrey Irish and Marc P. Keane at Kyoto’s Komaitei, a turn-of-the century residence along the Biwako Canal.

Author of more than 100 books and a lifetime of essays, Katō is widely translated abroad but best known to the English-reading world for just three works: his encyclopaedic study, A History of Japanese Literature (1991); a critical work on Japanese art, Form, Style and Tradition (1994); and his autobiography, A Sheep’s Song (1999). Born in Tokyo just after the First World War, Katō began his career as a hematologist but shifted his sights to writing in the aftermath of his visit to a Hiroshima devastated by the atomic bomb. Therein begins our story.

jsi: We’re all shaped by our experiences. I imagine for you that your visit to Hiroshima may have been a particularly important time. Is that right?

Katō Shuichi: Yes. Very, very important. First, it was the first time I had spent time with a foreigner. Well, come on, Japan was a closed nation, at war, right? There were hardly any foreigners in Japan, and I’d never had the chance to travel abroad either. So I was traveling with a foreigner for the first time. And it was a small group, about six doctors from the American team and ten from the Japanese. Plus technicians. And I was working with Dr. Lodge, just the two of us. We were doing a follow-up report on people who had been exposed to radiation during the bombing of Hiroshima, but had since returned to their village homes in the surrounding areas. It was just the two of us, in a jeep, going from village to village, for about ten days.

There were a lot of unexpected things on that trip. The biggest, this really threw me, we would go into a village, the occupying army, right, in a jeep, with a rifle, in army uniform, just a month after MacArthur had landed, and everyone would turn out to welcome us. That really threw me. There wasn’t any anti-American sentiment at all. Dr. Lodge kept explaining to the Japanese doctors that he carried the weapon because he was required to, not because he felt he needed it. He excused himself over and over. He didn’t act overbearing because he was part of the occupying army. Compared to him, in general, the guys who became commissioned officers in the Japanese army were a bad lot, but he was really civilized. And after ten days together, we became good friends.

It’s hard to describe what it was like for me to get to know an American. You see, most people never met foreigners in those days and, of course, a private discussion was out of the question. I was denounced for that, for helping out with the medical study, you know, for not criticizing the Americans, for supporting their study which, by revealing the effectiveness of the bomb, also effectively supported their nuclear strategy. So, there were some things written (about me) and to some degree I can see what they meant, but they had no idea, really, about who I was or about the particular American that I was involved with.

mpk: I’m very interested in your first impression of Hiroshima. How did you get there?

Well, we took a military plane from Tokyo to Iwakuni, then another to Tachikawa. There was an armed soldier in the cabin, but he was just a ‘teenager’.

mpk: Did you know what you were about to see? Had you seen any photos?

No, we hadn’t seen anything. Well, we had a report from Hiroshima. There had been some changes in the blood (of A-bomb victims). Something like anemia. But the doctors in Hiroshima had never seen anything like this before. Of course no one had, because it was from the effects of nuclear radiation, so they sent a report to Tokyo and since we were hematologists, we were sent to investigate.

mpk: Did you know it was an atomic bomb?

Yes, of course. But we had no idea what Hiroshima would be like. So we got in the plane, and the first thing I noticed was a ‘pin-up’ inside. In a military plane! You see, Japanese military equipment was the emperor’s equipment, it was sort of sacred. So I just couldn’t imagine the two together; a pin-up and a military plane? It was like a completely different society, a different language, and that alone was a shock. In any case, we never saw Hiroshima from the air. We landed and went in by jeep. We drove in and we could see across the entire city. There was nothing left. In Tokyo, after the fire bombings, at least there were things left, the remains of burnt buildings or concrete buildings, what have you, but in Hiroshima there was nothing. Literally nothing. Flat. Not one tree. No grass. It was September, right? But not even an insect. ‘Completely and absolutely nothing’.

mpk: Was it the shock of that scene that changed your life? Drove you from the medical profession?

No. It was the hospitals. You see we were sent on an investigative mission. A study. We were doctors but we weren’t there to treat or aid. And the patients, many of them really suffering, right, were simply turned into objects of our study. Objects for data collection. And there’s a hypocrisy in that I couldn’t abide.

mpk: Since the end of World War II, Germany has made it a point to apologize to neighboring countries regularly and emphatically. On the other hand, Japan’s apologies have been meager at best. What do you think is the main difference between the two countries that causes that?

Ohhh, yes. The biggest difference is the continuation of the ‘regime’. It’s somewhat true of Mussolini but the classic example is the Nazi regime whose members came from outside the established power of Germany. Hitler was a corporal, right? He wasn’t a general or anything, in any case he was not a member of the traditional ‘political, military, economic, cultural establishment‘. And he took power through violent force. And then that system fell apart. That’s not true of Japan.

Tōjō1 and the other Army leaders had complete control over Japan from the 1930’s, and their power base was within the army itself. It was a case of the establishment taking a change of direction and degenerating into fascist militaristic nationalism. That’s different (from Germany). And for Germany, after the war, the Nazis were somewhat easier to remove, after all they were outsiders to begin with. But in the case of Japan, things weren’t so simple because (the war leaders) in Japan didn’t come from outside the establishment, they were the establishment. So there was a strong continuity. And where does that show up? Well in many places but, for instance, who were Japan’s political leaders after the war? They were ministers from Tōjō’s cabinet. Take, for instance, Kishi Nobusuke.2 He was a minister in the cabinet that planned the attack on Pearl Harbor. The same cabinet that condoned forced labor policies [hundreds of thousands of Koreans and Chinese brought by force to Japanas thre wasn’t enough domestic labor], captive prostitutes for the army, abductions, and so on. And the person who executed that, perhaps you could say ‘brilliantly’ executed that, was the intelligent, capable cabinet minister, Kishi Nobusuke. And (after the war) that guy became Prime Minister! In Germany it would be inconceivable. A minister from Hitler’s cabinet? Impossible!

mpk: And so, because the regime continued it made it hard for them to apologize to countries that suffered in the war?

Sure. Government bureaucracies are organizations made up of specialists, right? So, if you take the whole thing away, it becomes impossible to govern. So, as for Japan, the occupying army came in, right, and they could have run the whole thing if necessary, you know, direct governance. But in that case, you’d have to bring in a huge number of specialists. From America, of course. It would’ve been unthinkable for MacArthur’s army to try to run a government of such size and complexity without help. In the end, they chose to govern Japan indirectly, that’s just to be expected. And that meant maintaining the existing bureaucracy. In Germany too, much of the bureaucracy remained in place, even the police. In Germany, in Japan, a large share of the police system remained after the war.

mpk: Didn’t the American army pretty much eradicate that…?

No, no. A lot was left. Bureaucratic organizations simply remain, no matter what. In Japan that persistence was absolute. The difference with Germany is the situation of political leaders. Adenauer, Brandt, Helmut Schmidt, the men who lead post-war Germany were all anti-Nazi, men who had fled the Nazi regime. But in Japan? We get Kishi Nobusuke, right? As far as people who were clearly against military nationalism and became political leaders there was Yoshida Shigeru.3 But Kishi and Satō,4 they just stayed on from before. So, in a nutshell, that’s the difference between Germany and Japan; the continuation, or not, of political leaders.

mpk: Does that difference account for Germany’s ability to make war apologies while Japan doesn’t seem able to do so?

Well yes, but also society and education. In the broadest sense, society itself educates, eh? So, school education but also mass media, movies, novels, everything, right? In Germany, all of that is ‘geared to’ an anti-Nazi message. Not so in Japan, right? There’s so much that isn’t said. The Nanking massacre, what have you. In that regard, Nanking and Auschwitz are treated differently. Japan tends to hide things, not talk about them. And this is not a result of government orders or police force, it’s more a ‘passive consensus’ within society in general. ‘”Let’s not speak about that.”’ Kyoto’s like that. It’s part of the traditional culture of the city. (Not revealing things overtly— Japan’s really good that way. There’s no law or police action to enforce it but, for some reason or other, you just know you should keep silent; speak out and it’ll be your own loss. Everybody’s in on it. Even newspapers with circulations in the hundreds of thousands, claiming they must respect the feelings of the general public, don’t speak out. The newspapers don’t write anything so the public doesn’t say anything. The public doesn’t say anything so the newspapers don’t write. In the end, nobody says anything!

So we have said that there was a continuation of bureaucracy and moreover a continuation of political leaders, and now we see that there is another form of continuity, that of certain social ‘mentality’. And that ideology is ambiguous. The Nazis controlled not through regulations but through an incredibly severe ideology including, of course, racial prejudice. For Japan, there’s the imperial system. Even now, they keep handing out imperial decorations. So, why does Japan not apologize? Well in Germany, until recently the official stance about all the Jews killed in Auschwitz was that it was not the German public-at-large who killed them, not the German army, it was the Nazis. Until about two years ago that was the story; the Nazis killed the Jews. Trouble is, for Japan it was the national army. What happened in Nanking, it was the army and nothing but that. But now they won’t acknowledge what happened there. There again, it’s a problem of the continuation of the regime. As long as it is a continuation from the past, it will be very hard to acknowledge the crimes of the national defence force. Same with Vichy.5 France also has a hard time acknowledging the past crimes of its military. For instance, one clear example is the government of Algeria. And America, too. Vietnam. The burning of villages and such, well that’s just the tip of the iceberg, right? There were an incredible number of civilians killed. And the question is, is that a crime of the army itself, as an organization? If that’s so, it won’t be acknowledged.

jsi: You’ve written that the particularly horrible thing about the Nanking massacre is that, unlike Auschwitz, Nanking wasn’t a planned act.

Yes. Spontaneous; not planned out at all. It wasn’t run on orders from the military commander, it just happened. That doesn’t mean that the commanders are absolved of responsibility in the matter. No. Not at all. After all, they kept silent. They didn’t try by whatever means they had to stop the massacre, they just kept silent. And it wasn’t just one event; it went on for days. So, of course, the commanders are responsible. And then after the war, all these guys go home and return to being normal family men, nice neighbors, just regular, quiet citizens, right? The guy next door with a nice family, you know, is, under certain circumstances, potentially capable of incredible brutality. According to the situation they’re in, ordinary people can go beserk, and if the same circumstances were to recur, the same people might do the same things again.

jsi: Do you think that is peculiar to Japanese or fundamental to all peoples?

kato: Well, of course it’s not just because they were Japanese, all people are capable of that but, then again, there is some aspect of being Japanese that allowed for it, in particular the aspect of Japanese society to ‘conform’ to the majority. Perhaps among Americans there are many people who would refuse; that’s the great part, I think, of individualism, and being faithful to one’s conscience. If your values are strongly internalized, then they won’t change easily with the circumstances you find yourself in. For Japanese that attitude is rare. Not non-existent, but certainly rare. There just wasn’t the environment for developing that kind of individualism. In the samurai class of the Edo period certainly there were many people who held some internalized values and were faithful to them. A great number. But since the Meiji period that’s been growing steadily fewer and nowadays, of course while there are some people like that they are rare and in general the degree to which most Japanese people link their values to their circumstances is very high. And of course this is exacerbated by the ‘group mentality,’ people following the majority.

jsi: Could you tell us a little about Japanese ethics?

I see it like this. In the fifty years since the end of WWII, Buddhism has provided little or no ethical background. Then there was Confucianism which didn’t exist in its pure form but still did provide some form of ethical system. But that was only until WWII. Then there’s the nationalism and emperor worship that has existed since the Meiji period (1868-1912). That required a sort of ethical discipline. But following WWII these various Confucianist-based ethical values were almost completely destroyed. The number one reason for this concerns the all-pervasive, extreme male-female prejudices of the Confucian system. After WWII, in light of the new interest in social equality and human rights, the conflict of these with the Confucian system became exceedingly clear and the system was not able to continue as is. It would be nice if they could have kept the good parts and gotten rid of the bad, but things don’t work out so well, so the influence of Confucianism general declined. No Buddhist ethics, no Confucian ethics. Christianity is too rare to be mentioned. Shinto and emperor worship? Well, among the ruling class there are some who still place importance on that, who try to benefit from it, but after all, those are the ideologies of the ruling class. In any case, that stems from after the Meiji period so its relatively new and hasn’t deeply permeated the general public and hasn’t been really vital in the fifty years since the war. There’s just nothing left, an ethical vacuum.

So there’s a vacuum, yet for instance, people follow traffic rules to a degree that allows driving; the streets are safe to the degree that allows women to walk alone, even at night; the crime rate for brutal crimes is very low. It’s natural to ask, “why”? If there’s an (ethical) vacuum, then why doesn’t everything become ‘chaos’, revert to ‘jungle law’. Only the strong survive. Why didn’t that happen?

Well, I think it’s because of this ‘group mentality‘. So the Confucian ideology that encouraged the extended family disappeared but family connections remained. And community connections remained. And as we talked about before, the group mentality remained pretty strong. So it’s a type of conformism, not loyalty but conformism or collectivism and although that is not truly an ethical system, it plays the role of an ethical system in society. So it’s ‘ersatz’.

But over the past fifty years family structure has gradually been breaking apart. And local communities too, especially agricultural villages the population of which rapidly declined after the exponential in growth of factories in the 1960s. And those villages, which had extremely strong communities, have gradually weakened. As the cooperative body of families and villages break up, the consciousness of belonging to a group also erodes. And since this group conscience is acting as a substitute for ethics, if, in the future it goes completely then there truly will be ‘chaos. Terrible. Frightening.’

jsi: What do you think of the attitude of Ishihara Shintaro’s6 views on Japan and Japan’s role?

Ishihara says the most impossible things. For instance, I too am opposed to Japan’s dependency on America, and its policy toward military bases is a little scattered, but Ishihara, well he’s a little different. He’s not just against the bases, or just proposing the elimination of all bases, from time to time he’s been calling for an independent Japan with full armaments, which includes nuclear weapons, of course. He’s actually written this. But this is just blatantly impossible. Japan going independent from America and stocking nuclear weapons, well, it just like going back to the past isn’t it? Let’s say we tried to do that within the next ten years, well we’d have the entire world as our enemies. The Chinese would rather die than allow that. America wouldn’t be thrilled with the idea of a nuclear Japan. Russia? Of course, they’d oppose it. Right? So, America would be against it. Korea would be vehemently against it. Russia’s against it. Europe would say, “not again?” There wouldn’t be a single country supporting Japan in the world. So when Ishihara proposes a ‘pure Japan’ he’s living in a dream. The whole idea just keeps slipping away from reality until it becomes fantasy.

jsi: Can you imagine a Japan without the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty (Anpo boshō jōyaku)?

Yes, I believe it is possible to attain a situation without the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, In my opinion, getting rid of the Treaty is not such a big deal. Where’s the threat? Korea? Mmm. In any coercion or attack there’ll always be benefits and losses. Everything has pluses and minuses, right? I don’t think there’s a country for which the benefits outweigh the losses. China’s not a problem, Russia’s not really in the position right now. Korea? North or south, well certainly there’d be some benefit, but not so much, and the losses would be catastrophic. And to begin with, there’s no such intent shown on their part.

Secondly, though this isn’t as important, they don’t have the capability. Theoretically, they have the capability to attack, let’s say a missile attack and they could destroy parts of Japan, but after that, they simply don’t have the capability to occupy Japan. Present-day China? There’s no way they could occupy Japan. Even Taiwan. Their intention is strong in that case, but let’s say China did attack Taiwan, even if America didn’t intervene, well, it’d end up a real mess. And Japan? I think it would be impossible; technically impossible.

jsi: A bad situation for all concerned.

Yes. That’s right. It might amount to some form of harassment but a ‘serious aggression’? I don’t think they have the necessary military capabilities. Europe couldn’t do it. Nor Russia. In fact, the only country these days with the ability to cross over to another continent and attack and occupy another country is America. And the only fear in northeastern Asia is Japan itself. If someone like Ishihara gets control of Japan in the future, Japan would be second to America. The problem isn’t threats against Japan, the problem is Japan’s potential threat to other countries. So, the long and short of it is that even if the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty was dropped, and even if there were no nuclear safety umbrella, Japan would be just fine. No big problem. In fact, better, because it would remove some of Japan’s potential to threaten others.

mpk: If the Peace Treaty were abandoned wouldn’t that require Japan to enlarge its military to some extent?

The Self Defense Forces are already pretty big, but I think a smaller force would be just fine. There just isn’t really a role for them to play now. There’s no real threat against Japan now and Japan has, for the moment, no intention to use military force against other countries. Whether or not there may be a potential for either in the future, there is none now. Since the danger lies more with what Japan might do to other countries, rather than what they might do to Japan, I feel that there is no real problem with a reduction in Japan’s military forces; something like a ‘Coast Guard‘.

jsi: Living in Japan, how do you keep up with what is happening in the rest of the world?

Well, of course, the Asahi Shimbun newspaper and NHK alone is not going to do it. So in my case, for daily newspapers, I get the International Herald Tribune. For other countries, to get their newspapers daily is too expensive so, for France, I get the weekly summary of Le Monde, Selection Hebdomadaire. With that you can grasp the most important aspects of what France is talking about. For Germany, there is a weekly called Die Zeit and for Italy, La Republica. So I get the gist by scanning those four.

mpk: What about CNN?

Yes. If something big’s happened I’ll look at CNN or BBC.

jsi: BBC and NHK are so different, sometimes it’s hard to believe they’re reporting the same news.

kato: Oh yes. NHK is just interested in natural phenomena, right. Weather, earthquakes, floods. Things that affect everyone. They really focus on that. Next is kids. “So-and-so kindergarten went on a field trip today. Children and mothers are having a good time playing together. NHK.” They present it really majestically but, come on, it’s just a kindergarten field trip. Then there’s birds, animals, flowers. And if there’s news related to people it national news, right. NHK doesn’t run any in-depth, international news, and the Asahi Shimbun doesn’t print much. As far as the Japanese media is concerned were still in a state of national isolation.

jsi: What are your personal religious beliefs?

Me? Right now I would say that I do not believe in a god. I am not a theist. I pretty close to being an atheist but more than a radical atheist I’d say I’m ‘not a theist.‘ Well, come on, they’re just about the same thing right (laughs)? My mother was Catholic and I was taken to church when I was young, and because of that you might say I have a certain close feeling for that religion. Even now, as an adult, in my professional life, I find I have a great interest in Catholicism, the New Testament, and the broader culture that surrounds them. I’m not very knowledgeable but I do have a great interest. In any case, I would think far more interest than the average Japanese person. Also, within the Japanese context, of course you’ll come in contact with Buddhism, and within Buddhism what attracts me most is the whole peripheral culture of Zen. I’m not sure you’d call that religion but I find fascinating the whole culture that derives from Zen. Before I said I reject theism and was closer to atheism, well that might be part of my attraction to Zen. In any case, Zen is not theism but whether it’s a religion at all, now that’s a subtle question. In any case, I have a deep interest in the culture of Catholicism and of Zen. You might say a kind of ‘affection’.

If you look at the history of Christianity objectively, the first real threat, the first powerful enemy of the Catholic church, was ‘natural science‘; Galileo and the theory that the earth revolves around the sun. And next, of course, Darwinism. So in the face of natural theology or natural philosophy, this natural science was a real threat. Another was that, from Descartes to Kant, deism radically abstracted the concept of god and thereby radically moved away from the kind of belief in a god with a personality or individuality. God is still a god but has become a so-called ‘philosopher’s god‘ infinitely removed from a ‘personal god’. And through that rationalism, there was a kind of liquidation or cancellation of the concept of god, but since god can’t be eliminated, rather the concept was abstracted instead. That’s up to the end of the 19th century. Then into the 20th century, the situation changes. Natural science is no longer the enemy, rather cultural anthropology and the study of comparative religions, those kind of self-styled history of religions take its place. Because according to the study of comparative religions, well you can find Maria everywhere, right? The predecessor of Maria is first seen in Egypt, then moves over to the Middle East, then Rome. And seen historically, it’s no longer a doctrinal question of Maria or the virgin birth, seen historically there are any number of Marias. She becomes one of many ‘goddess faiths‘ and if you see things that way, wholistically, it’s a real threat (to the traditional religious doctrine). And we find that Christmas is really folklore and, of course, so are the devil and angels.

So first there was the threat of natural science in the 19th century, then of cultural anthropology and such in the 20th century and now, in the past thirty years or so, we have a ‘comeback’ of sorts of natural science in the form of neurobiology; the incredible phenomenon of neurons firing within the brain and so religious phenomena become the firing of a certain nerve cell; close to a kind of physics. And the important thing is no longer ‘god‘ but ‘spirit’.

jsi: What about Japan’s New Religions?7 How do they stand?

Well, the New Religions are somewhat different. I think the most important thing in connection to the New Religions, and this is not limited only to Japan, is that they have appeared since the onset of the ‘high tech’ society and a high tech society is based on completely rational, ‘scientific technology’. But the nature of things high tech is that they are extremely useful but the mechanism that drives them is not understood by the average person. Before the advent of ‘electronic injection’ if your car broke down you opened the hood and fixed it yourself, or at most, you went to the gas station and had them fix it. But with electronic injection, well its going to take some sort of ‘factory specialist’ to analyze and fix the problem.

Or television. You flip the switch and there’s channel after channel of programs but as to why those images actually appear, you don’t understand the mechanism. And you put all those things together and everything around you is high technology and eventually even one’s own living environment itself comes to be ‘beyond your understanding’. So when things go wrong, you get fired or your company goes through down-sizing, whatever, you don’t have the inherent habit of figuring out for your self what to do. So you turn to Asahara-san8 for help. I think that kind of New Religion is deeply connected to high tech.

jsi: Considering the influence of the computer, what do you think will become of kanji bunka [the culture of using Chinese calligraphy]?

Yes. Computers have a really big influence, the biggest part of which is that people can read but they can’t write. It used to be that people needed to write to some degree just to get by in daily life but now, with word processors, if you know the sound of a word, and if you can recognize the character, that’s all you need. You know, if you need a language, you’ll learn it. Kanji take time to learn, and it’s difficult to learn but you manage to do it. Anyone can. But, if it’s not necessary, no one’s going to learn it. So people will steadily lose their ability to write kanji.

jsi: It’s a vicious cycle. As the number of kanji used in newspapers becomes fewer people are able to read less and then the kanji used become even fewer, and it just goes on. When I interviewed Umesao Tadao [see issue KJ43] he said that he thought that kanji should be largely done away with. “It just can’t be helped.” One reason I admire Japan is for its kanji culture so it was a real shock for me to hear that. I would think you might have different thoughts…

Me? Precisely the opposite. Well, in the past I had thought about that — the abolition of kanji — but now, contrarily, I’ve taken the opposite point of view; the revitalization of kanji. Make kanji education stronger. Until the middle of the 19th century there was a kind of “kanji sphere” including China, Korea and Japan and because of that educated peoples could communicate through writing. All the Chinese classics. The written language was kanbun, ‘classical written Chinese’ and because of that, all three countries could communicate with each other. For the educated class it was easy to write, so as long as you had paper and pencils, well not pencils, a brush, right, you could communicate. It might have been high level diplomatic negotiations or matters of etiquette or, of course, literature, just for one’s pleasure. For instance, if an official visitor came from Korea, Japanese Confucianists or poets might compose Chinese poems. Korea was considered to be an advanced nation at the time. So they could carry on really high-level communication that way; social matters or government matters. It had a real impact. It’s not something they could have communicated orally because, already by the Edo period, the pronunciation of the words in China and Korea and Japan was different. What they couldn’t get across by speaking, they could through writing. So in a way it was like Latin in medieval Europe.

mpk: Kanji was a sort of lingua franca?

Not quite. For certain periods communication through kanji was possible. I suppose with Vietnamese, even with Thais. The pronunciation of classical Latin is known, it’s been reconstructed. And when it was used, the Italians spoke Latin with an Italian accent and Germans with a German accent. But the Catholic church, the Vatican, had such a large influence on what was being communicated that whether the priests were German or Italian, they spoke Latin in an Italian manner so they could just start up speaking and understand each other. At least the priests could. But in the case of China that’s no longer true. So kanji was a ‘quasi’, or a ‘semi lingua franca.’ When written it could be broadly understood but not when spoken. In any case, even if not completely, kanji was a kind of lingua franca and that’s an incredible thing. An incredible thing! So rather than think about something ridiculous like making English the official language of Japan we should focus on the strengthening of kanji culture.

Developing this kind of ‘lingua franca’, a regional international language for Japan, China and Korea, would lead to more trusting relationships and ultimately be the foundation for cultural creativity and regional security. The relationship of Japan and China in East Asia is like that of separatism in Europe. With the years of war and such, complete integration is probably impossible but in any case, a kind of trust has developed there. For instance, at this point, I don’t think there is a Frenchman who believes that Germany would attempt to launch an attack against France. Not just the national leaders either. It’s just incredible. After all, there was the Prussian War in the 1870’s and then World War I and World War II and in all three cases it was the Germans who were the aggressors and yet very few Frenchmen believe that there could be a fourth case. That’s amazing. And why? For one thing the unequivocal German attitude that Nazis are completely and utterly criminals, which is expressed on a daily basis. Compared to that, the Japanese have done absolutely nothing.

mpk: The acceptance of responsibility?

Just nothing. Close to zero. So, I think that’s the most important thing. That and language. That’s why I say that we need to strengthen kanji culture among Japan, China, and Korea, but I doubt it will come about. The things I suggest rarely come true. But I keep hoping.

mpk: I think you can really sense the expressive power of kanji in poetry, especially short poems.

Yes. That is originally the best aspect of kanji. First of all, ancient Chinese civilization was extremely developed. With regard to presently extant cultures, the only thing comparable to ancient Greco-Roman civilization is ancient China. Well there’s Egypt, but that died out right? As for civilizations that continue to this day in European culture the foundation is Greco-Roman, in other words Hellenism, and ‘Judaism’ or ‘Christian culture’. The only other example comparable is Chinese culture. That’s the first point. And that can’t be thought of separately from kanji culture. So that’s the second main point, that kanji culture continues, and it allowed for the development of an abundance of things. Hey, that’s not something you can just snap together in a century or two.

The third point is that what’s called modern culture originated in Europe. What’re you going to do when you try to import that knowledge? When it came time to translate, that was the Meiji period in Japan, and China is into that stage right now, kanji exhibited its ‘tremendous’ capability. To take the point to the extreme, without kanji there would have been no translations. Without translations there would have been no modern Japan. In short, without kanji there’d be no shinkansen (bullet train). That’s because so many social organizations and social ‘ideas’ including legal systems, begin with translations. And how do you translate? Well that’s where kanji came in. It’s so important I think they should make a kanji shrine!

The finesse of a man like Motoori Norinaga9 just couldn’t be attained with only hiragana. Neither could legal terms like the Napoleanic codes or technical works like medical information. You know, there was just no pre-existing terminology. One way, for instance with the word jiyū (自由liberty), two kanji were put together to make a new word. The kanji combination jiyū appears quite often in classic Chinese texts, especially in the likes of Lao-zi (Lao-tse) and Zhuang-zi. The word shows up a lot but it has the meaning of a ‘social gathering‘ not ‘citizen’s liberty‘ or ‘freedom of debate.’ Close but really not the same. So the meaning changed from the abstract concept pre-existing in Chinese tradition to the Western concepts of ‘freedom‘ and ‘liberty.’ It was used in translations to express the thoughts of John Stuart Mill. So that’s one way (kanji was used). Another would be that they would look as hard as they could in classic Chinese but, not finding any good examples, they’d make up a new word from scratch. In that we see the inherent linguistic creativity of kanji. If you put a couple of kanji together you can make any word you can think of. The classic example is kenri, [権利]the ‘rights‘ in ‘human rights.’

mpk: Kenri was invented in Japan?

kato: Yes. That was made in this country. It’s not in Chinese. At first it was written two ways; one with the ‘ri’ of ‘rikutsu’ or ‘risei’ (理) and another was the ‘ri’ of ‘rieki’ (利). Anyway it’s the second that lasted. And, interestingly, that word, kenri, has been imported into Chinese language and now is used there, pronounced in a Chinese manner. It was because of kanji that the Japanese translators were able to put a few ideograms together and make a new word.

And also the types where the word existed but the meaning would be shifted toward a new purpose like ‘kakumei’ [revolution]. ‘Kakumei’ comes from Mengzi [Mencius10], from the Wu dynasty, in the four-character expression ‘ekisei kakumei’ [change by divine intervention 易姓革命]. ‘Ekisei’ implied that the world would change, in other words that the dynasty would change. And ‘kakumei’ meant ‘divine intervention‘ in other words an edict from heaven would change the dynasty, the lord or king —at least the name. So as the ruler’s name changed so did the will of heaven. It’s what we now call ‘heaven’s mandate.’

That’s a little bit different from the ‘French Revolution’. In the French revolution it wasn’t that the king’s name changed, so the meaning is different, but one thing that’s a little similar is that the Chinese word kakumei changed to mean ‘revolution’ [as in France]. And again, that was via Japan. It went to China and became the shingai kakumei (October 1910 Revolution) and the bunka kakumei (cultural revolution) and so on. So the words “Great Cultural Revolution” actually came from Japanese; originally. In any case, all of this just shows the ‘extraordinary’ creative linguistic potential of kanji.

mpk: There are certain customs we tend to think of as “typically Japanese,” such as the standard image of the gruff, distant Japanese father/husband. Or, for instance, giri and ninjō or tatemae and honne.11 Can you tell us from what era these stem?

Well, the kind of guy who basically pays little attention to his family becomes common from the Tokugawa period (1600-1867), the samurai class of the Tokugawa period. Before that it was different. And in the Tokugawa period there were really two important groups: the samurai class and the farmers. Oh, and then there were the townsfolk (chōnin, merchants and artisans) who were influenced by, and displayed the customs of, both the samurai and farmers. But the Tokugawa era samurai didn’t go to war, they were bureaucrats, middle class bourgeoisie who worked for the provincial lord. And there was, to some degree a Confucian ethical base to the samurai class. Now when the Meiji period begins, (with the elimination of the samurai class structure) we find the advent of the “salaryman” and men go to work for Mitsui Corp., or what have you, instead of the lord, but the bourgeoisie samurai values, to some degree, remain.

mpk: So are giri and ninjō or tatemae and honne samurai values?

Ohhh no. Well, tatemae and honne are classic aspects of the samurai class. But giri and ninjō are completely representative of townsfolk culture. And the farmers don’t pay any attention to any of that stuff. Their villages are based on ethics of cooperation, very clearly, and the organizational system of the central government didn’t really penetrate the villages. So, for instance, division of male and female is completely different, like arranged marriages; those are definitely indicative of samurai society and was continues by the middle class bourgeoisie of the Meiji period. But giri and ninjō, that’s really interesting. It begins in the Edo period and is ‘exclusively’ an attribute of the townsfolk.

mpk: Didn’t the performance arts that the townsfolk supported, like the puppet theatre (bunraku or ningyo joruri, often feature scenes of giri and ninjō?

Yes, of course. Giri and ninjō are the classic themes of puppet theatre. You see, giri is all about rules, and those rules, that ‘law and order’ was that of the ruling class, the samurai. And because it came from outside the townsfolk society, they never fully internalized the concept of giri. So the giri of the townsfolk was a superficial thing. The townsfolk had their own values, and that’s ninjō. Giri is rational, it’s the historical, social attribute of the samurai class and for the townsfolk, its an external concept. The concept that stems from the townsfolk themselves is ninjō. In French, a “pleased consensus.” And then it becomes institutionalized into townsfolk life. So in puppet theatre we see ‘lovers suicides’ [shinjo (as the result of not being able to resolve giri and ninjo)]. The townsfolk did not rebel against the tenets of giri; they accepted them. So if a servant fell in love with his employer’s daughter, which was prohibited by giri, he would agree, this is wrong. Yet that wasn’t quite satisfactory and what came out from inside, that was ninjō. Giri and ninjō in state of tension. The farmers don’t have it because they haven’t accepted the nature of giri. The samurai don’t have it because giri is already of their kind. Only the townsfolk. That’s what Chikamatsu captured.

jsi: Are there parallels in European social history?

Yes, there are parallels but the European knights, well, they had a system of ‘chivalry’, right. And that included a kind of “worship of the feminine,” sort of a twisted form of love, you know, for some princess locked up in a castle they’d never seen and all that. Devotion. Well, that kind of sentiment is ‘absolutely and totally absent’ from the lives of Japanese samurai. So perhaps the number one difference between Japanese samurai and European knights was their attitude toward women with the knights idealizing them. But in fact that kind of idealizing was a form of prejudice.

jsi: The face of Mary comes to mind; a virgin yet bearing a child.

Well, in a society (like medieval Europe) that strongly suppressed love relationships, it was one form of self-assertion of love. So, if you think of it that way, the double suicides of Chikamatsu and the worship of Maria — an idealized female — on the part of the knights, while different in expression are also similar in some ways.

mpk: And tatemae and honne?

Well no matter where you look, whatever age or whatever culture, you’ll find tatemae and honne. The unique thing about those sentiments in Japan is the degree of ritualization and with that, the degree of separation between the two. And the classic form exists among the Japanese samurai; they ritualize everything. Take seppuku [ritual suicide]. Even death is ritualized. And the peak of that ritualization for samurai was the Edo period.

mpk: So the words tatemae and honne also stem from the Edo period?

Yes, yes, of course. They didn’t say that in the Heian period. It was very much the Edo-period samurai class.

mpk: The Genji Monogatari is often called the world’s first novel. What was it about Japan in the 10th-11th century that allowed for that development?

Well, this isn’t just my opinion, many people say this, but I would say it’s the nyōbō13 culture that allowed it. The nyōbō were not outsiders, they were inside the court, but neither were they at the center of things. They lived a ‘marginal, peripheral existence’. For an ‘observer’ this is an ideal situation. That’s actually a lot like me, on the margins of Japanese society, without power to influence things, yet not outside and so still informed of inner circumstances. [In the West] Marcel Proust is the best example. He wasn’t from a high aristocratic society yet he wrote novels about the ‘haute societe’. He was able to attend the salons and at one such gathering, he was standing of to the side of the room and talking with someone who asked him “Qu’est-ce que vous faites ici?” to which he answered “J’observe.“14 There were people there who had much more influence and power and yet, they did not have the observational skills to be able to write ‘A la recherche du temps perdu.’15 I don’t think you can do both. And the court of 17th century France is much the same. Corneille, Racine, Moliere.

Then, there’s another case at another time. Just after World War II, in the northeast of America, there were sociologists, many of whom were Jewish.16 So they were insiders [to American society], in the way a Frenchman or Japanese wouldn’t be but they were also, because they were Jewish, not in central positions of power. This allowed them to be ‘observers, very sharp observers.’ So there are similarities there: the author of The Tale of Genji, 20th century American sociologists, and Racine and Moliere. Another those groups share is their ‘intellectual refinement’. They were all highly ‘sophisticated’.

mpk:So what allowed for The Tale of Genji to be created in Heian-period Japan was a kind of social recipe: one part culturally refined society, one part marginal observer?

Yes, and [in the case of the Heian period aristocrats or Louis XIV’s court], the societies were closed and politically and economically stable. Murasaki Shikibu17 lived completely off taxes, right? Didn’t work at all; she was a ‘pure and absolute consumer‘. She didn’t make anything, other than literature. Marginal observers in create a very special form of literature, like The Tale of Genji.

jsi: You’re a critic, and so an observer yet today I get the sense of another Katō-sensei as an activist. Is that correct?

Observer. Yes. You’re right about that. I’m certainly not at the center of the vortex. But this a society that does not invite criticism. I don’t get involved in elections. I can see the good in many of the parties. The more the better. But I don’t do public speeches or in any other way support any of the parties. Maybe it’s because I was formerly a scientist. Or because I was an academic. I like to see things objectively, and when I do, I like to express those thoughts. You know, seeing things objectively is a pretty difficult job. Not to jest but you can’t do it part-time. And I have the responsibility, when I write, not to make mistakes [in my objectivity] and also to write as persuasively as possible. I put all my energy into that. So whether my writing will be popular to a broad audience or make me affluent, well I’m not so interested in that. The purpose of my own writing, something I feel very strongly about, is democracy. I want to work to protect, you might say defend, democracy in Japan. So, of course there’s peace and harmony, yes peace and harmony is good but not in any form.

jsi: And what form should we be striving for?

kato: Well, I would say ‘human dignity.’ To me, that’s as important as democracy. And I will fight against any and ‘all possible forms of slavery’, including ‘intellectual and sentimental slavery’. But, of course our society is one based on power struggles, right? And power is open to abuse, right? So I do not accept the system of order imposed by those in positions of power. It’s like the word erai (eminent, celebrated). That’s used to describe someone who has accepted the hierarchy set up by those in power. I’ll sometimes use it, but that’s not right, people have got to have their own values. And I don’t use the word sensei.18 Well, that’s different for a real teacher, you know, someone who actually teaches. But I don’t use sensei in connection with politicians. Even for someone I has a great deal of ‘sympathy’ for, like Takako Doi, the head of the Socialist party. I just would never say, Doi-sensei. So I don’t praise politicians and, likewise, I never talk down to students. My attitude towards people remains equal that way. So I may meet a student and think, “Now here’s a real sharp one,” or it may be the Prime Minister and I think, “God he’s an dull-witted, idiot.” Whatever. It’s for me to decide, not something I take from an externally conferred ‘hierarchy’.

jsi: How do you imagine world peace? Do you see the United Nations playing a role?

Well of course peace in any form is important. War is horrific. The loss of human life, the destruction of human rights. War is unparalleled in that regard. And as a way solve problems, violence is almost always counter-productive. And of course this will be in the far future, but the must be some form of world government, something which has the power to regulate sovereign states. Right now that power is limited to the United States, right? Not China. Not Russia. And in the present United Nations, even thought there are five countries in the Security Council with veto power, the United States is really the only true world power, and so the balance is way off.

mpk: But you think that would be good. To have a world government.

Yes. I think so. It will be very difficult, but if you really want to end wars, the only way will be through a regulatory body, a world government with the power to enforce its ideals.

mpk: I believe it would be correct to say there was no concept of Asia until after the Edo period. What do you think of Asia, as a concept, and how does Japan fit within that Asian concept?

Well to begin with, I try not to use the word Asia. It’s sort of a geographical convenience, but I don’t think there’s and meaningful content in the word. In Europe, for instance, you have many countries, each with it’s own culture and language and yet here are many common aspects as well. Some very strong common links. Judeo-Christian culture, Hellenism, and concept of Roman civil law. So at the roots, there is a very basic interconnecting culture. So even in the 20th century, in Europe, in any case Western Europe, we find a very similar quality of life, level of industrialization, technological development, degree of education and so on. For instance, in Western Europe, at least in the 20th century, there’s no country with an illiteracy rate higher than 50%. But you can’t apply any of those standards to Asia. You can apply the name to a certain geographical area but, India? China? It’s just not the same. And religion? Well, Buddhism passed through the entire region, but it almost doesn’t exist any more in India so you see it doesn’t have a continuity. There is just no linking cultural “grammar” in the region. And illiteracy, well there are countries with more than 50% and those with less than 5% side by side. Technological development, level of education, customs, so much is different. So if there is a distinct region it is the area of influence of Chinese culture and with that, of course, kanji culture. But as for Asia, it really exists only in the negative; what it is not. Not Europe.

mpk: So there is no true Asia but, still, Japan has neighbors—China, Korea—and the relationship between the countries is not always the best. What is the first step to improving that situation?

Mmm… The first step? Well, I think there’s two, actually. The first thing is cultural exchange between private individuals. The sum total of many, many small activities. And that should be done as soon as possible. The second, and this of course must involve the government, is getting over the past. Like the Germans have done, you know, to the point where they say, “Come on. Haven’t we had enough of this?” To the point of being obstinate. Japan just hasn’t done enough. Well, of course, from Japan’s point of view they’ve been doing it, but from the point of view of those overseas, that intention is simply not getting across at all. Chinese? Koreans? No way. They just don’t feel that way. Nobody believes that Japan’s settled with its own past.

And how do the Japanese people think about all this? Well they have absolutely no interest. But you can’t pull the wool over anyone’s eyes. This has to be addressed directly and honestly. From private citizens to government action. And the German attitude would be a good model. Just look at the German weekly magazines. There isn’t a day that goes by without the words “settlement of the past” being printed. Even now. Even now! So if you want to learn some German, well the Japanese always go first for some food words like, “it tastes delicious” but more important than learning “es shmeckt mir sehr gut,” “that tastes real good,” you should start with “vergangenheiss verberdungen,” “settlement of the past.” That’s how important it is. That’s how often you hear the phrase. Even now! Fifty years after the war. It’s not a question of how many times you’ve apologized. There some people who say “but we’ve already apologized three times,” but come on, how can you be so stupid? We must simply keep on apologizing over and over. Forever!

That’s right. Forever!

1. Tōjō Hideki (1884-1948): Army general and Prime Minister during most of World War II.

2. Kishi Nobusuke (1896-1987): In Tōjō’s cabinet during WWII, imprisoned as a war criminal after the war, Prime Minister 1957-60; instrumental in forming the conservative Liberal Democratic Party in 1955.

3. Yoshida Shigeru (1878-1967): Politician, opposed Tripartite Pact between Germany, Italy, and Japan, as well as Tōjō’s war-time government. Arrested by military police in the last months of WWII.

4. Satō Eisaku: Politician; indicted in the 1954 Shipbuilding Kickback Scandal but protected from prosecution by Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru.

5. Vichy was the site of (and thus the common name for) the French war-time government

which supported German actions.

6. Ishihara Shintarō (1932– ) Writer turned politician best known in the West for co-authoring (with the late Morita Akio, founder of Sony) The Japan That Can Say No. At the time of this interview, mayor of Tokyo.

7. New Religions, shinkō shukyō, refer to the numerous sub-sects of Buddhism and Shintoism that have developed in Japan since the end of WWII.

8. Asahara Shoko was the leader of the Aum cult that carried out the sarin gas attack in Tokyo in 1995.

9. Motoori Norinaga (1730-1801): Classical scholar of the Edo period who fully developed the National Learning (Kokugaku) movement, which focusd on linguistic studies of ancient Japanese texts such as the Kojiki. Like Kato, Motoori began his career as a medical doctor.

10. Mencius (390-305 BC): Latinized name for Mengzi (Meng-tzu), Confucian writer; his writings, Mencius, comprise one of the Four Great Books of Confucianism.

11. Giri (duty, social obligation) and ninjō (empathy or kindness), tatemae (official stance) and honne (real intention)

12. Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724): Edo-period playwright of kabuki and ningyō-jōruri (puppet theater).

13. Nyōbō were the ladies-in-waiting of the Heian period (794-1185) court who were

trained in, among other things, the literary arts.

14. “What are you doing here?” “I observe.”

15. Novel by Proust, translated as In Search of Lost Time.

16. David Riesman, sociologist (Harvard), author of The Lonely Crowd; Robert Lifton, psychoanalyst (Yale, New York City University), active in psycho-sociological analysis of problems in the U.S. and abroad; Noam Chomsky, linguist (MIT), also engages in politico-social criticism of American society.

17. The author of The Tale of Genji, a nyōbō.

18. Sensei (the one who goes before) is used as a suffix for anyone considered erai: teachers, doctors, lawyers, and also often politicians.

From KJ48, published October 2001

Marc Peter Keane is a landscape architect, artist and writer based in Kyoto, Japan. His work is deeply informed by Japanese aesthetics and design: simplicity, serendipity, off-balance balance, and natural patinas. Working in situations as diverse as a 350-year-old house in Japan and a contemporary museum in the United States, he designs singular gardens that are both beautiful and contemplative. Keane is also known for his ceramic sculptures and his many books on Japanese gardens and nature including, Japanese Garden Notes, Japanese Tea Gardens, and The Art of Setting Stones. He hs been a long-term KJ contributing editor.

Jeffrey Irish, also a long-term KJ contributing editor lives in Kagoshima Prefecture, where he has twice been elected head of his village (see ‘In a Garden of Learning,’ KJ79). He is the author of Island Life, and several books in Japanese, and translator of a number of books including The Forgotten Japanese: Encounters with Rural Life and Folklore, by Tsuneichi Miyamoto; Doctor Stories from the Island Journals of the Legendary Dr. Koto, by Dr Kenjiro Setoue; and My Nuclear Nightmare: Leading Japan through the Fukushima Disaster to a Nuclear-Free Future, by Naoto Kan. He also films and directs documentaries for local television in Kagoshima.

Images sourced from Amazon, Facts and Details and University of California Press.