[A]t 36, Kyoto-born butoh dancer and choreographer Katsura Kan has done what would have been unthinkable when the butoh movement began three decades ago. He has survived as an independent dancer, working outside the established butoh companies, after having left the acclaimed Byakkosha group in [seven years ago]. His own multinational butoh company, the Saltimbanques, has featured dancers from North America, Europe, Australia and Israel as well as Japan. He has also appeared as a guest dancer with other international dance groups.

When and how did you first get interested in butoh?

My father was an actor, and my mother was a Takarazuka-style dancer, but I didn’t think about becoming a dancer myself until about ten years ago. I started learning percussion and dance, and then I hit a wall. I needed a way to make progress, and to get to know my body. I’d become accustomed by habit to one kind of physical pattern, so I had to find something to get me out of the old pattern, and help me discover the source of my body’s power.

And that was what led to butoh?

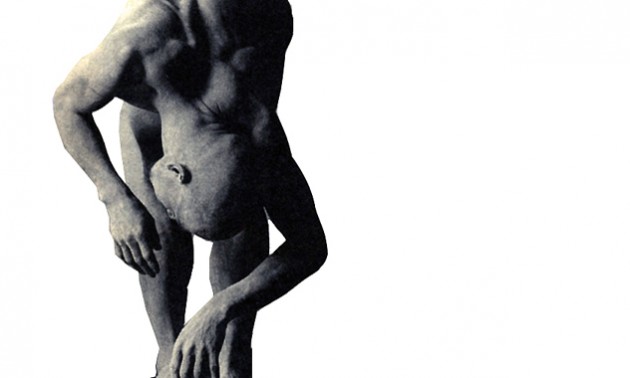

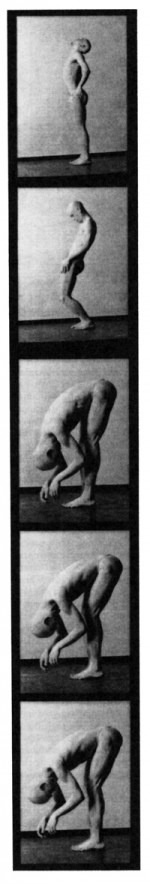

Not directly. It was only by chance that I was looking for a way to get over the wall at exactly the same time tat Byakkosha was forming in Kyoto, so I joined them and toured with them in Japan, Southeast Asia and South Korea. I was with Byakkosha for three years, and then I got very interested in the Noguchi Method of physical training. Noguchi Taiso is very Japanese, but is unique even among Japanese style of bodywork. It’s the opposite of the Western idea that the body is anatomical, that it’s a system of bones and muscles that have to be developed and coordinated, usually in ways that are very forceful and fast.

The main principles of Noguchi Taiso are friction and gravity. Noguchi imaged that the skin of the body is a flexible bag or vessel full of liquid that should move around freely, like waves. The water in the body is drawn downward by gravity, but it also wants to move up into the air; and it also seeks the light, which is why we have eyes. So when you practice Noguchi Taiso, you don’t have to strain and use a lot of energy. You just relax, and let the liquid in your body flow naturally and easily.

Byakkosha has no method of butoh, so Noguchi Taiso gave me what I needed: a set of principles and techniques that I could use for training my own body.

How did you decide to leave Byakkosha and work as an independent butoh dancer, and form your own international butoh group?

How did you decide to leave Byakkosha and work as an independent butoh dancer, and form your own international butoh group?

The experience of working with Byakkosha was very good. They were doing some new and very original work. But I wanted to find my own dance. I was still mainly interested in understanding my own body.

When I started teaching my own butoh workshop three years ago, I had no plan to form an international butoh group, or anything else. I just wanted to teach people who were interested in butoh. It just happens that in Japan, most of the people who are interested in butoh are not Japanese. Part of the problem is butoh’s identity. The Japanese are very conservative. But butoh itself is a very underground thing. It has a negative and dirty image.

I have a side business of teaching Japanese language. Well, Japanese don’t come to my school to learn Japanese. Only foreigners do. It’s the same with butoh, or other Japanese styles of movement. Not many Japanese are interested in learning them right now.

Your company, the Saltimbanques, has performed in Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto. Have the foreign members of your company gotten the same reaction that other foreign butoh dancers have — that it’s very interesting, and it’s very nice that they’re doing it, but it’s not really butoh?

Butoh dancers, and other Japanese dancers, don’t know very many foreigners and they no way of knowing what foreigners can or can’t do. One advantage of a butoh teaching system based on Noguchi Taiso is that anybody can know it. If a foreign dancer wants to learn butoh, it doesn’t matter what his or her background and culture is. Anybody can do it.

Last year, when I did my summer workshop in Israel, I saw some olive trees that have been growing beside the Sea of Galilee for 5000 years. They reminded me of butoh. So did the obelisks I saw in Egypt, and some of the things I saw in Europe, especially the London underground. There are butoh-like images everywhere.

In Japan there are always people who believe that foreigners can’t understand the Japanese language in dept, or can’t become good at kyogen, or whatever. I don’t believe this. If the teaching method is good, and is designed to teach anybody, from anywhere, then it will work, and they’ll learn.

Over the last 30 years, butoh has begun to coagulate into a conventionalized art, and now dance critics argue about which of the new variations are really butoh, and which are not. What is true butoh, as you see it, if there is such a thing?

That’s very hard to say. When Tatsumi Hijikata first created butoh, it started at a very high level and was almost perfectly complete, both artistically and spiritually, so that nobody else could develop it much further, much less surpass it. The original butoh that Tatsumi created had the very deep spirituality that’s typical of art from the Tohoku region. As butoh spread through Japan, it had to be adapted to the styles of other areas. Companies such as Dai Rakuda Kan, Sankaijuku and Byakkosha have all created their own variations on Tatsumi’s original idea, but none of them has matched the depth and quality of his work. None of them has taken butoh beyond where Tatsumi left it. That’s what I want to do but I don’t yet know how to do it. Butoh may have already passed its peak. In Europe there are dancers who are now working in post-butoh styles.

In a way, today’s Japanese butoh groups are like traditional theatre companies. In noh you have the Kanze School and the Kongoh School. They work separately, but they don’t see themselves as competing with each other. They feel that competition only wastes their strength.

The weak point of butoh companies isn’t competition with other groups. They have the internal problem of company leaders becoming iemoto. Ashikawa Yoko, without really wanted to exalt herself, has been elevated by others into the iemoto of the Ashikawa Ryu. There is also a Dai Rakuda Kan Ryu. This is dangerous.

Which of the butoh companies do you admire most?

I admire Dai Rakuda Kan. They’ve developed a kind of butoh that’s a lot like kabuki. Sankaijuku’s work is very beautiful, and has become very close to modern dance; they’re one of the groups who started with butoh, then moved in the direction of modern dance. Byakkosha has been successful in creating perormances that are like happenings, or art events. There are now many butoh dancers who think very seriously about what kind of butoh they want to create, and how they can combine butoh with other dance styles. I especially admire Ashikawa Yoko; after Tatsumi Hijikata, she’s certainly the most important figure in the butoh movement.

Kyoto doesn’t have very many butoh dancers. What are the special challenges and pitfalls of doing butoh in a city as conservative, and as closely tied to its past, as Kyoto?

There are many butoh dancers in Tokyo, but the only ones who are active in Kyoto right now are Byakkosha and me, and maybe three others. Tokyo people are very busy. They’re always dealing with new information. They want to become famous, to win prizes and appear on TV. So they’re always on the run. But Kyoto is a much slower place, and because it’s an important center of traditional art, it always views butoh and other kinds of modern dance against a classical backdrop.

What’s the future of butoh? Where will it be 20 years from now?

Butoh has already become one of the most influential forces in contemporary dance. Some of the new choreography that Maurice Bejart has done in Lausanne is full of butoh movements. Butoh is about to change into something much more international, and we’ll see more and more fusions among butoh, classical ballet and modern dance. This will have an effect on the shape of dance everywhere. Western dance will also be influenced by classical Indian dance.

This is ironic, isn’t it? Tatsumi Hijikata intended that butoh would be something completely new, having no connection with either classical Japanese dance or Western dance. Maybe this idea of a “pure” butoh was impossible, like expecting butoh to live in a test tube.

Human beings change. Today’s young Japanese can’t understand the old Japanese spirit. As people change, and their ideas change, dance has to change too. And people have to move. When new students from Europe come to my workshop, I get new ideas about dance from them. And as foreign butoh dancers leave Japan, they begin to create American butoh, French butoh, English butoh. They invent new movements in butoh style. I know an English butoh dancer who’s been criticized in London for doing something that only looks like butoh. But he’s really doing something that has the form of butoh, and resonates inside with the history and culture of the place where he’s dancing. He’s filling the form with something new, something that is his own.