But the mural is bold and powerful, and striking.

“Oh, it’s ugly,” some said at first after seeing the 5.5 by 30 meter mural in the station. Tarō wouldn’t have cared. Nor would he have cared that most people seem to appreciate it. He wasn’t the type of artist to gloat over his masterpieces, or to wallow in self-appreciation, and he certainly didn’t covet his creations, or even dwell upon them for long. Large, public works were only one facet of his creativity, but whatever he did, Tarō wanted it to be seen, which is why he did not sell his creations to private collectors. He also wanted his work to have an effect, however small — whether it be the chuckle elucidated by a cute little face at the bottom of a whiskey glass, the smirk prompted by a stool that refuses to seat anyone, or the “whoah” of disbelief brought out by a 70-meter tower resembling a sun-worshipping artifact.

Tarō’s landmark 1950 oil painting, Law of the Jungle, expresses his intentions well. A great monster impales victims with gigantic teeth as it rampages through the trees. Animals flee, frightened monkeys watch helplessly, and indifferent people look on from afar. But the brilliant red demon has a zipper running along its back, and the viewer is invited to reach in and open it to reveal the true nature of the creature — nothingness. As Okamoto explained it, people might be frightened by this violent beast, but in reality it is nothing. There is no need to fear it; just grab it and expose it for what it is. Myth of Tomorrow is similar in its intensity and handling of a serious issue, but all of Tarō’s works share a similar purpose — to elicit a response… and perhaps a tiny change. And should the viewer misunderstand, Okamoto was never one to brood over the failure of the public to grasp his meaning. He wouldn’t hold a grudge, even against one journalist who called him a better art critic than an artist. He might have just had a laugh over that, for he didn’t really care to be called an “artist,” anyway. According to Okamoto Toshiko, his long-time assistant and life partner, when asked his profession Tarō’s answer was simply, “human.”

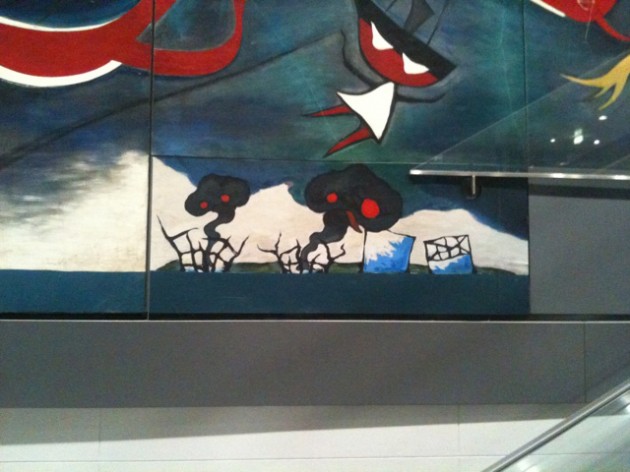

Myth of Tomorrow represents the culmination of Tarō’s concern over the horrors of war and the fear of atomic weapons. But it doesn’t lament the effects of war or contemplate man’s inhumanity to man so much as it says, “This is what happened. Let’s acknowledge it, remember it, and move on.” He had painted many smaller pieces in oil prior to this massive undertaking, exploring related themes, and he also did numerous studies for the work, but nothing quite like Myth of Tomorrow. The mural is not only about Hiroshima and Nagasaki; it has a great deal to say about the nuclear arms race.

Along the bottom of the mural one can see the surface of a large body of water. Bobbing amidst the waves is a likeness of Fukuryū-maru 5, the tuna fishing boat subjected to heavy radiation by the massive March 1, 1954 Castle Bravo thermonuclear test at Bikini Atoll.

This was a landmark event for the anti-nuclear weapons movement in Japan. The ill-fated crew members of the ship, thought at the time to have been well outside the danger zone around the Bikini testing site, suffered terribly from the effects of the “ashes of death” that rained down on them for hours after the blast — one of the largest nuclear explosions ever. And not only the crew were affected. By the time anyone realized what had actually happened, the ship’s cargo of nearly 17,000 pounds of fish had already been shipped out for consumption across the country. Fish quickly disappeared from tables all over Japan and the national market collapsed as the government scrambled to track down all the irradiated seafood. Mothers across the country banded together in protest against the cold war race to build the biggest bomb. The parallels to the situation Japan found itself in, following the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011, are obvious.

Tarō’s perspective on art had been forged during the decade he lived in Paris. (His parents took him there in 1929, and in 1940 Tarō fled on the eve of the German invasion.) In Paris, he was influenced by encounters with Pablo Picasso — both Picasso’s work and the man himself — and he surrounded himself with creative people. He became involved with Abstraction-Création, an association founded in 1931 by Belgian sculptor Georges Vantongerloo, Piet Mondrian and others to advance abstract art and also to counter the rising surrealist movement. For its members, abstraction was freedom itself, vital for them in that era of ever-increasing state subjugation of individual expression across Europe. Tarō — young, inexperienced, and still struggling with the French language — was much liked by the group, and they took him under their wing. His friendships extended to photographers as well. He got to know Robert Capa, Man Ray, Brassai and Florence Henri, and among them he was more than a tag-along. Capa’s companion and fellow photographer, Gerda Pohorylle, was actually better known as Gerda Taro, having taken Okamoto’s first name as her professional last name — a move which helped her match Capa’s own adoption of a catchy four-letter moniker to replace the less memorable Friedmann. In addition to these and other Paris circles in which Okamoto moved, he studied for a time under the legendary French ethnologist Marcel Mauss. He learned to play the piano as well — a skill that would bring him great pleasure in his later years when he played on the upright in his studio, said to have been a gift from poet Yosano Akiko.

Tarō would probably be happy with the placement of his great mural in Shibuya Station, for there it can be viewed by the maximum number of people. But he was not always mainstream enough to have his works displayed in such places. After WWII, when he returned to Tokyo from military service in China, he went to the site of his family home in the Aoyama district only to find a field of weeds. The allied bombing campaigns of 1945 had done away with his childhood home and with it all of the drawings and paintings he had stored there. Okamoto simply started over, almost entirely from scratch, forging a path into the postwar Japanese art world, which was dominated by masters of traditional forms and techniques. Other artists who worked on the margins were generally less radical than Tarō. To the critics his colors were ghastly, his style naïve. They wanted to see some element of tradition, but he gave them none of that. Yet his work was distinctively Japanese; it just wasn’t what they expected. Most of the art experts who didn’t criticize Tarō ignored him, and as a result the general public remained largely unaware of his work for years.

For his part, Tarō despised the Japanese art world of the late 1940s and early 1950s, or more precisely, he despised the way that the elite and elderly critics controlled the art scene. He did not hesitate to castigate them, writing opinion pieces in magazines and newspapers. When they lambasted him for his bold use of primary colors and then waxed eloquent on the rustic grandeur of ancient Buddhist temples and iconography, he pointed out that many of these had in fact originally been brightly painted and decorated. He also had no interest in the arguments between leading critics and historians of the time over which master had made which Buddhist statue. To him, each was an individual work of art in and of itself and only the form mattered. Tarō made waves in 1947 by declaring in a newspaper article “The stone age of art is over!” For Tarō, tradition changed by necessity. Tradition, he argued, belonged to everyone, not to the elite guards, and it was meant for everyone. It cried out to be grappled with and bent and twisted into new forms and to be injected into new trends, which in turn also needed to be embraced fully to be understood. The new will invariably replace the old, but this interchange of processes — and the forms that the new will take — are up to us.

By the time Tarō built a new studio and house for himself on the site of his prewar family home in Aoyama in 1954, he had begun to attract some positive attention, largely due to the support of a few loyal friends. One strong supporter was author/politician Ishihara Shintarō, known in the 1950s as a writer of unconventional fiction, such as Season of the Sun and Crazed Fruit. Ishihara wrote the cover notes for a paperback edition of Tarō’s bestselling 1954 book, Art of Today, in which he praised Tarō for his radical views on contemporary art, and for his eloquence. The Ishihara family remained close to Tarō over the years.

Several art critics also helped Tarō in the early postwar period. One especially strong supporter in the art world was Kaitō Hideo, who arranged for Tarō to have solo exhibits in both New York and Paris in the winter of 1953, giving him his first chance to return to the City of Lights since his departure in 1940. There, Tarō was reunited with Max Ernst and Jean Arp, among others, who had been like brothers to him in the 1930s. Although the Paris show was deemed a great success, the New York exhibit failed to attract much attention; after all, it was held in Tarō’s absence because he was unable to obtain permission to enter the United States, either from Tokyo or from Paris. No clear explanation was ever given, but his name had probably wound up on a blacklist because of his affiliation with avant-garde art and literary circles in early postwar Tokyo, especially Yoru-no-kai (The Night Club). Tarō wasn’t strongly political himself, but such groups tended to lean to the left, and some ranking members of Yoru-no-kai had ties to the Communist Party. After all, it was the era of the Second Red Scare, and the occupation of Japan was shifting from its initial goals of creating an egalitarian democracy to building a strong bulwark against the spread of socialistic ideology. Nevertheless, Tarō remained extraordinarily productive, which eventually paid off.

By the 1980s Tarō had become somewhat of an art icon. His “Tower of the Sun” had served as the centerpiece of the Osaka World Expo in 1970. He had authored numerous books and articles on art, tradition and society. And he had become associated with, and influenced, a number of the most famous designers, artists and writers in the country. Among his creative friends and associates were Isamu Noguchi, Arakawa Shūsaku, and Abe Kōbō. Tarō was brimming with ideas. Whenever he spoke, his partner Toshiko would take notes so that he would be able to go back over them and return to certain ideas. Tape recorders were insufficient because with recorded tapes it was too difficult to find the right thought, but when he said “tape, tape” – that was Toshiko’s signal to switch to note-taking mode.

Tarō wanted badly to share his ideas with the public, and would try just about anything to do it. He used a helicopter to write in the sky with a light. He painted a dirigible and had it fly over Tokyo. And, at Toshiko’s suggestion, he went on television as often as he could. Tarō did commercials, and the line he spoke in one of them — “Art is explosion!” — earned him great fame. But he only did commercials on his own terms, saying what he wanted to say and nothing more. He didn’t deliver lines penned by anyone else, nor did he explicitly endorse the products being advertised. He simply made brief performances to convey his messages. Tarō also appeared on variety shows — most notably “What a Fantastic Night!” with Morita Kazuyoshi (better known as Tamori), and Kuroyanagi Tetsuko’s program. He chatted about all sorts of things, giving his opinions on whatever came to his mind, often surprising both the host and other guests with his unconventional ideas — ideas that most people did not expect to come from a man in his seventies. He even dressed up in strange costumes and danced. Always true to the avant-garde, he continually strove to help the public think outside the box — both through his art and actions…through his very life. Moreover, he wanted them to have a bit of fun. But he may have largely been misunderstood. Although Tarō’s art was becoming increasingly visible, and he had found considerable fame, it is likely that most viewers merely pointed and laughed. They might have been impressed by his paintings and sculptures, while being confused about the man himself.

No, the art of Okamoto Tarō was most definitely not deemed worthy of the public’s attention — or tax money — when he made his early post-war debut with a solo show at the Mitsukoshi department store in Ginza. But today his works are everywhere. One might encounter a Tarō sculpture in a secluded corner of Tokyo, outside some non-descript train station, or in front of the National Children’s Castle. Tarō’s massive tower still stands at the site of the 1970 Expo in Osaka, his home in Aoyama is open to the public as a museum, and there is a larger museum dedicated to him in Kawasaki, the city of his birth.

And now, Myth of Tomorrow dominates the interior of one of the busiest rail hubs of Tokyo, offering a message — posing a question — to Japan of the early 21st century as it grapples with a new nuclear emergency. The controversial Japanese art group Chim|Pom answered this question in their own way by attaching a graphic postscript to the lower right corner of the great mural seven or eight weeks after the Great East Japan Earthquake — a small Tarō-esque depiction of the damaged Fukushima Dai-ichi reactors, complete with black mushroom clouds. Although their action provoked criticism, it is unlikely that Okamoto himself would have taken offense — his response would have probably fallen along the lines of his rather nonchalant reaction to the destruction of his massive ceramic reliefs, Sun Wall and Moon Wall, along with the old Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building that housed them, due to that structure’s replacement by the current tower in Shinjuku. In fact, Tarō would likely have been pleased by the extra attention, if nothing else. Myth of Tomorrow was actually executed in Mexico during the 1960s for a hotel which was never built, and the panels subsequently went missing. One of the last things Tarō’s partner Okamoto Toshiko did during her lifetime was to find the badly-damaged missing panels and arrange to have them brought to Japan for repair and display. Unfortunately, she passed away in April 2005 at the age of 79, only weeks before their arrival. But thanks to her, and to the efforts and assistance of a great many other people, including Ishihara Shintarō, Tarō can now communicate with the masses passing through Shibuya Station.

Even if his messages have been misinterpreted, they are still out there, and they are reaching the people. Being ignored, misread, or laughed at didn’t bother Okamoto Tarō. If only one person were to find inspiration and experience some sort of change from seeing Myth of Tomorrow or any of Tarō’s many other works, he would consider it job well done.

Donald C. Wood, a cultural anthropologist, is an associate professor in the Graduate School of Medicine, Akita University, and Akiko Takahashi is an independent researcher in Akita. This essay is based heavily on her research.

Photograph by Nakahara Mizuki; other images by Donald C. Wood