Animals take specific roles in all cultures, roles more often than not, that perhaps mirror more closely their human counterparts. What would that worldy and wise, but not too wise, tanuki (raccoon dog) have to tell us about Japan? Here, Yamamoto Fumiko, a faculty member of the East Asian Languages and Cultures Department at the University of Kansas, introduces some of the many roles the wily tanuki plays in Japanese popular culture.

-John Einarsen

Aki no kure

Hotoke ni bakeru

Tanukikana

Autumn eve-

Changing into a Buddha

Is a tanuki.

During the Edo period, haiku poet Yosa Buson added gaiety at dusk one forlorn evening when he sang with amusement of the tanuki’s trick. In that era the tanuki was frequently associated with metamorphosis and with Buddhism, perhaps because its round head resembles the shaven head of a monk. The tanuki was believed to change not only into a monk but into various other forms.

Sometimes a scheming old man has been awarded the unsavory title of tanuki jijii (old man tanuki), just as it was given to the wily first Tokugawa shogun, Ieyasu. A fox, the tanuki’s counterpart in witchcraft, was often compared to female figures because of its slender body and stealthy movements. An Edo senryu comical verse ridicules a cheating game played between a courtesan and a customer in a gay quarter:

Kitsune o ba

Bakashite kaeru

Furu-danuki

Bewitched even the vixen

And ran off,

That old tanuki!

Here the tanuki gains the upper hand but it was a rather rare victory. In Jūni-rui kassen emaki (The Picture Scroll of the Twelve Species’ Battle), a mid-fifteenth century picture scroll, the tanuki revealed his identity as a buffoon. In this comic scroll, the tanuki offered to judge poetry at a meeting of the twelve zodiac animals. These animals became offended by the tanuki’s inflated ego and throttled him. The humiliated tanuki persuaded the animals who had not been included in the gathering to help him get revenge, and waged several wars against the zodiac animals. The tanuki’s troops were eventually defeated and the tanuki renounced the world and became a monk. However, the scroll concludes, he could not give up his fondness for poetry. The tanuki in the scroll is a creature proud of its art but whose talent is easily mocked by other clever animals, and he is a creature who resigns itself to the status of an anchorite yet cannot completely relinquish the joy of this world.

Although the tanuki in the scroll seems to have only achieved limited poetic accomplishment in the eyes of the other animals, the tanuki’s artistic talent has been well known since antiquity. In the Nihongi (720), an episode tells of a tanuki (actually it was called a mujina but the tanuki, mujina and anaguma share similar characteristics and that all became combined into the tanuki’s image in popular culture) which transformed itself into a man and sang a song. Later commentators suspect that the story was a fabrication by a young girl who tried to conceal the evidence of her secretly serenading lover. The episode attests to the belief in the tanuki’s magical ability to transform itself and the tanuki’s longstanding ability to mimic many sounds.

The most well-known affiliation of the tanuki with the sounds it creates is the tanuki’s belly drum. The tanuki’s belly drum is said to make the sound “ponpoko-pon.” This sound has been immortalized in a modern children’s song “The Tanuki Music at Shojoji” by Noguchi Ujō with a melody by Nakayama Shimpei. The melody was used by an American singer, Eartha Kitt, in the 1950’s and her song about Shojo ji’s hungry raccoon, embellished by her smooth and twining humming between verses, was re-imported to Japan. I understand that the song has contributed to her revived popularity in Japan in recent years. This must be a sign of the Tanuki’s magical powers. The original children’s song describes a harmonious scene where a group of tanuki are beating their belly drums under the bright full moon, but some of the original old legends tell of the tanuki who competed with a human lute player until its belly skin became torn.

The tanuki never seems to know its limit. In addition to its drum sound, it is believed that the tanuki can mimic whatever sounds it hears. If there is a woodcutter around, it immediately echoes the chopping sounds. The tanuki even imitates the hissing sounds of a steam locomotive and there are quite a few stories which record nightly encounters between a train and a tanuki. The incidents end when the tanuki, too confident and daring, does not jump off the train track in time. Yanagita Kunio suggests that the tanuki’s ability to fool humans with sounds is a sign of its undeveloped witchery, since the fox possesses a more highly developed ability—it can fool humans with visual illusions. The suicidal tanuki in the locomotive tale with its blind and total absorption in its own talent moves the listener to pity.

The tanuki is not always lovable and its vicious side is epitomized in the wellknown story of Kachi Kachi Mountain. In this tale, the tanuki fooled an old man and an old woman, killed the old woman and made her into a stew which he then served to the old man (a Japanese version of The House of Atreus). The story closes with the tanuki drowning in the sea as the result of being tricked by a rabbit. The rabbit acted to get revenge for the old man. This story is believed to be a coined narrative made of two separate tales put together: the first part which testifies to the tanuki’s successful trickery of humans, and the second part which reveals the tanuki’s surprising stupidity at the hands of the rabbit. The story has several versions in which different animals such as a bear, monkey or wolf compete against the rabbit’s craft. But the story which involves the tanuki, rabbit and humans is perhaps the most well-known. In this version the tanuki, which has been considered by humans as a delicacy when made into tanuki-jiru (tanuki-stew), turns the tables on its predators, and makes baba-jiru (old hag stew). Although this story is gruesome, the complex activities of devouring each other in this version may be one of the reasons for its enduring popularity. We are not sure how this version has come about but the tanuki in the popular tale has impressed people as a trickster who eventually falls prey to his victims.

The tanuki’s encounter with humans does not always produce conflict. The popular story of Bun-buko Chagama (Bubbling: Teakettle) contains two happy elements: a miraculous tale of a teakettle which serves tea endlessly and the tanuki’s thankful repayment for a human kindness. At Morinji, a temple at Tatebayashi, a tanuki who was transformed into a priest named Shukaku served tea continuously to the good people who payed homage at the temple. The teakettle which he used is still kept at this temple. The teakettle has furnished another story of a tanuki and a junkman. In this story, the tanuki which was saved by the junkman transformed itself into a kettle and earned him a fortune by presenting a show of tightrope walking for the spectators. The junkman donated the tanuki-kettle to the temple so that it would rest peacefully there. In both versions the Bun-buku Teakettle carries the auspicious thought of opulence.

Both sides of the pathway leading to the central hall at Morinji, are flanked by rows of cement tanuki painted with bright colors. The spirit of propagation, the-more-the-merrier attitude, which is often found in Japanese popular culture, has even reached the holy arena. Because of their large size, these statues of tanuki in various shapes at Morinji look a little too menacing to be friendly but all of them have a droll humor with their round heads, big round eyes, protruding bellies, and enormous scrotums, even though some are wearing monk’s robes.

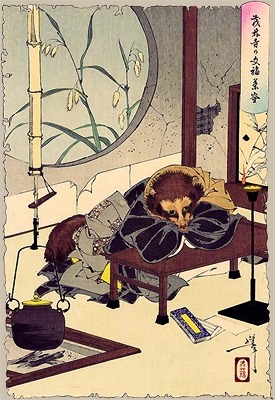

The tanuki’s scrotum, which is one of his humorous attributes, is reported to be eight mats wide. There are many folk tales in which the tanuki bewitches a traveler and entertains him on a carpet with an illusory feast of horse dung. This magic usually stops when the guest happens to drop a spark from his pipe on the carpet or finds some curious hair sticking out of the carpet and tries to pull it. The carpet screams “Ouch!” and shrinks immediately, throwing the bewildered guest out on the ground. The tanuki’s magnificent physical endowment has captured the fancy of many artists but Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s nineteenth-century woodblock prints of the tanuki rank among the best because of their preposterous playfulness and rich details. His tanuki finds many uses for its immense and pliable scrotum. It serves as a weight in a weight-lifting contest, becomes a net for scooping up fish in the river, and works as a head covering in a case of a sudden shower. Because of this visibility and openness in treating the scrotum, Kuniyoshi broke the sexual taboo.

The tanuki’s scrotum is very obvious in perhaps the most popular tanuki figure—the sake-buying tanuki, sporting a sedgehat and carrying a sake-bottle and chit book. These ceramic tanukis, which are made in the Shigaraki area, often decorate the entrances of eating and drinking establishments. The statue beckons, sake flows liberally in the store, and a merry time is promised. This tanuki shape is such a common sight that its peculiar organ no longer offends even the eyes of a timid observer.

The popularity of the tanuki has much to do with its humorous and winsome image. With its plump body, awkward movements and simple-minded trickery, the tanuki presents a comical, safe and manageable impression compared to the cunning fox, the other trickster. It has been observed in the koala bear craze, or in panda fever, that cuteness is one of the necessary qualities in creating a fad in Japanese popular culture. “Kawaii!” (“Cu-u-te!”) has the power to pull any sacred image down to the level of the cult of popular culture. Once I saw a store full of nothing but fluffy tanuki mascots, some with umbrellas, some with babies on their backs, and some with scarves over their heads, and all these tanuki fit the description of cute and cuddly.

The irony is that in present times when cities sprawl into country sides and many people have never had the opportunity to see the wild tanuki in its natural habitat, the tanuki’s popularity has increased as never before. Perhaps now that it has become disassociated from nature, the human imagination is able to increase the tanuki’s transforming power. The tanuki used to represent a male figure but now has emerged as a female with ample breasts. Its reclining pose is seductive and enticing to male customers at gift shops. When gilt handbags became fashionable for young girls, the tanuki with a gilt bag appeared immediately at souvenir stands.

The tanuki has been transformed into chopstick holders, coasters, and many many other useful items. It is often a popular figure in comics, and in a cartoon section in the weekly magazine, Shukan Asahi, it appears regularly to give, surprisingly, common sense remarks about the crazy human activities depicted in the comics. Novelist Inoue Hisashi recently entertained his readers with Fukkoki (The Record of Belly Drum), using many tanuki tales set in the Shikoku area. A few years ago a movie was made which depicted tanuki as heroes. The advertising phrase which appeared in the newspaper was, as I recall, something like, “The tanuki are human!” The line between tanuki and humanity has become blurred. Now people see in the tanuki only what they want to see, and most of the time, they see human traits. With the tanuki’s amazing adaptability and its perennial appeal to the populace, the tanuki’s future in Japanese popular culture indeed appears to be both promising and enduring.

– From the book , Old Kyoto, A Guide to Traditional Shops, Restaurants and Inns by Diane Durston

Long, long ago, near a small temple in the mountains, lived a very old tanuki who delighted in tricking nearby villagers and passing travelers. Many had tried, but none could put an end to his mischief.

One day, the two monks of the temple were talking of this problem when the elder one said to the younger:

“I have heard that tanuki tricks people using his magic balls. If they could be gotten away from him, perhaps that would put an end to his foolery. It certainly wouldn’t hurt to give it a try.”

With that, he rose and went off to the mountains seeking tanuki’s den. It took many days, even though the den turned out to be large enough for the monk to enter on all fours. Once inside though, he humbly confronted tanuki, saying:

“Hello, Tanuki-san. I’ve come a long way to see you because I’ve heard that you have magic balls you use to perform quite astounding feats. Could I possibly have a look at them?”

Tanuki, who had been found mid-nap, yawned and said:

“I do have such balls, as you say, but I don’t like to display them, since they’re more important than my own life.”

The old monk pleaded, saying:

“One so wise as yourself – I’ve come very far, and I’m very old. It would mean so much to me to see such magnificent balls before I die—please let me have a look.”

Tanuki thought a moment, then said expansively:

“Well I’ll hold them in my paws for you, but only for a moment.” Whereupon he flashed them so quickly that the monk didn’t get so much as a glimpse in the dim light filtering into the burrow.

“My old eyes couldn’t catch them in this darkness; won’t you let me hold them a moment in my own hands?”

“If I should let you hold them, you’ll steal them.”

“But I’m a monk,” the other protested. “I never lie! Please grant an old and truthful monk’s last wish and let me hold your balls!”

Tanuki gazed at the monk for a quiet moment, then said pityingly:

“Very well,” and handed his magic balls to the monk, who immediately pocketed them and, scrambling quickly out of the bur row, ran back to the temple as fast as his trembling legs would carry him.

Arriving there, he handed his prize to the young monk, and after getting his breath back, said:

“Tanuki’s magic balls! No more trickery from him! Let’s have a festival to celebrate. I’ll go tell the villagers. Don’t show my balls to anyone till I get back.” Whereupon he turned and headed toward the village.

As the young monk waited in the temple rejoicing in this good fortune, now and then stealing a glimpse at the treasure, a mendicant monk came down the road. As he approached he called out to the young monk, saying:

“I’ve heard you have quite a pair of balls.

Could I have a look? Pay my respects?”

The young monk, in his pride at the new and powerful acquisition, could not restrain himself and, ignoring the old priest’s command, showed the balls quickly to the visitor. “Please don’t just flash them like that; I’d like to heft them a bit, if I could, for they’re of impressive size.”

Seeing the doubt in the young monk’s face, he went on:

“I’m a monk! Would I lie?”

No sooner had the young monk put the balls into the stranger’s outstretched palm than the visitor transformed himself into the tanuki he was and, clutching his regained balls, scampered back into the mountains.

The old monk, upon returning to the temple with a number of villagers, demanded:

“Where are my balls?”

The young monk lowered his head, saying mournfully:

“I showed them to a mendicant monk who turned out to be tanuki. He lied to me.”

“Of course he lied, he’s tanuki! I should never have left my balls in your hands!” So saying, the old monk set off at once after his lost treasure, and indeed tried many times thereafter, but tanuki was even smarter now, and played so many tricks that the old monk never again had the balls, and tanuki has been up to the same old mischief ever since.

From the Folktales in Tango, Kori Monogatari by Shozaburo Hosomi & Hunada Kikaku. Retold by Ichikawa Michiko and Robert Brady.

Photo of the small building with ceramic tanuki (Sake Kai Tanuki) typically found in front of businesses by John Einarsen.

Emaki Scroll “十二類絵巻” courtesy of Kyoto National Museum https://www.kyohaku.go.jp/jp/dictio/kaiga/juni.html

Kuniyoshi print “其面影程能写絵 猟人にたぬき金魚にひごいっこ” courtesy of Ota Memorial Museum of Art www.ukiyoe-ota-muse.jp/