Japanese graphic artists have been employing imaginative aerial perspectives for more than a millennium, since transforming the older Chinese-derived Kara-e style into the distinctively Japanese Yamato-e genre. Its fukinuki-yatai (“blown-away roof”) bird’s-eye view perspective was highly effective (no pun intended) especially in Heian-era emaki hand-scroll narrative illustrations of the classic Genji Monogatari (Tale of Genji). This perspective was also used in scrolls depicting the lives of historical figures, and later appeared in paintings on byobu folding screens, reaching another high point in the rakuchu-rakugai-zu cityscapes of the early 17th century, typically presenting views that might suggest drones were filling the sky much earlier than is commonly believed.

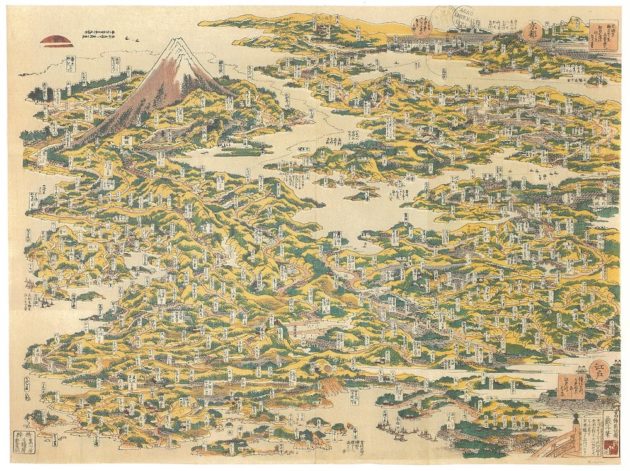

By the early 19th century, travel had shown up on the popular radar, and images were appearing that took birds’-eye perspectives to, yes, another level. In 1804, Kuwagata Eisai produced “A Picture of the Famous Places of Japan” (Nihon meisho no e), an astounding woodblock print surveying the whole expanse of the Japanese archipelago, including over 700 minute place-names, various well-known local attractions such as the whirlpools of Naruto, and Miyajima’s “floating” red torii gate, with even a glimpse of the distant peaks of Korea on the horizon.

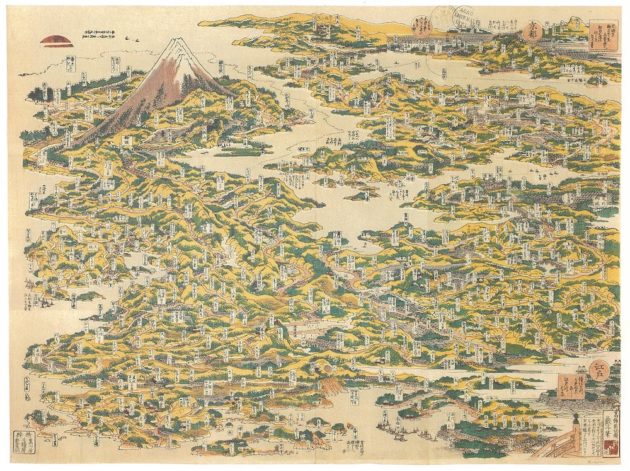

The prolific artist Katsushika Hokusai is best-known for his innovative woodblock series of Thirty-six Views of Mt Fuji (1830-32), which includes his iconic Great Wave, created in his early 70s. Not so widely known is Hokusai’s earlier (1818) depiction of The Famous Places of the Tōkaidō Road in One View (Tōkaidō meisho ichiran), an aerial vista through which the 550km road zig-zags without regard for cartographical accuracy. Inscriptions name villages, towns and local attractions, and Mt Fuji reaches up into the stratosphere. Hokusai’s non-traditional landscapes may have inspired the well-travelled Utagawa Hiroshige’s Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (1833-34), meticulous vignettes of travel along Japan’s main overland route between Kyoto and the Tokugawa capital, Edo.

The Tōkaidō’s stations were established in the early 17th century, at the beginning of the Tokugawa shogunate, a time when the most prevalent reason for travel (apart from trade, and regional daimyo’s ceremonial processions up to Edo), was pilgrimage. In fact, the 53 stations are said to correspond to 53 encounters experienced by the young Indian pilgrim Sudhana in the Gandavyuha section of the Mahayana Avatamsaka Sutra. (Seeking out a diverse array of enlightened teachers, he finally learns from the bodhisattva Samantabhadra that wisdom is only of value if used for the benefit of others).

By the 1830s, as seen in Hiroshige’s richly detailed Tōkaidō prints, the travel industry was hardly developed; a trip from Kyoto to Edo was mostly undertaken on foot, and could take two or more weeks to complete. Also popularized by Jippensha Ikku’s comic novel Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige (Shank’s Mare), serialized from 1802-22, this classic road trip fell out of fashion after just a few more decades, due to Meiji era modernization. The Tōkaidō main railway line connecting Tokyo and Osaka was opened in 1889; by train the journey took a mere 20 hours. By the early 1920s railways linked most of Japan, and road transportation was also expanding.

Rapid urbanization, industrialization and other social transformations set the stage for much more widespread development of tourism. In addition to building seamless transportation infrastructure and grand hotels, it was essential for this fledgling industry to provide promotion materials that allowed the new middle class to clearly visualize the logistics of travel in this modern age. In Europe, Baedeker Guides and Murray’s Handbooks for travelers, introduced in the early 1830s, fulfilled similar purposes but were essentially text-based. Japan’s thriving graphic and print tradition was instrumental in forging a characteristically Japanese solution.

Yoshida Hatsusaburo, “Hiroshige of the Taisho Era”

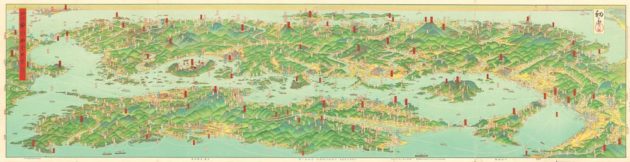

Known as “the modern Hiroshige,” Yoshida Hatsusaburo (1884-1955) was born in Kyoto and trained from the age of ten as an apprentice yuzen textile designer. After military service in the Russo-Japanese conflict, from 1907, he studied Western painting before becoming a commercial artist and finding his niche as a distinctively original cartographer. His first success was a birds’-eye view route map produced for the Keihan Electric Railway, connecting Kyoto (Gojo) and Osaka (Temmabashi), in 1913. Famously, it was praised as “beautiful and easy to understand” by the young Crown Prince, later enthroned as Emperor Showa.

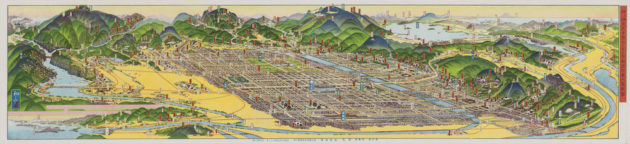

His Taishō meisho zue-sha (Taisho Famous Places’ Illustration Co.), later renamed simply Kankō-sha (Tourism Co.), specialized in aerial panoramas of significant attractions, towns, prefectures and even entire regions. Uniquely, some of them also incorporated “fish-eye” peripheral U-shaped distortion. These colorful maps characteristically featured intricately streamlined transportation networks: steamships, steam trains, early automobiles, buses and streetcars.

In 1918 Yoshida set up his business headquarters in Tokyo’s Ginza, and in 1921, more than 100 of his images embellished the special Railway Guide published to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the introduction of rail services; it was reprinted over 40 times. After his Tokyo office was destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake of September 1923 (he produced a graphic aerial view of the city in flames), he moved to Inuyama, in Aichi, and then to scenic Hachinohe, in Aomori, before finally returning to Kyoto in 1953.

In 1928 he was responsible for Kyoto City’s official map and attractions guide for the Kyoto Grand Exposition commemorating the imperial enthronement. The English version included the following commendation:

Mr. Yoshida traveled extensively all over the country to make illustrations for the Railway Guide published by the Japanese Government Railways; he has been in every spot famed for its scenery or its historical interest…

How popular his works are may be estimated by the fact that nearly 80 percent of high-class guide maps published by railways, steamship companies, hotels and other corporations and individuals concerned with travel, have been executed by him.

Sixteen years have elapsed since he gave to the world his new idea of picturesque maps, and during that interval he has made over 460 maps. These maps have been prepared for Government publications, for supplements to such influential newspapers as the Osaka Mainichi and the Osaka Asahi, and for numerous other books and pamphlets. It has been roughly calculated that his maps have adorned more than twelve million individual specimens of these various publications.

Overall, Yoshida was credited with creating over 2,000 maps in his lifetime, including locations in Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria and Sakhalin. One special project was connected with a remarkably popular campaign by the Mainichi newspaper to identify Japan’s eight most scenic landscapes for the newly-inaugurated Showa era. Within one month, over 93 million nominations had been mailed in (from a population of around 64 million!), resulting in designation by an eminent selection committee of eight renowned landscapes, 25 famous sites, and 100 vistas. Yoshida (with the assistance of apprentices) produced a folded magazine insert of the eight landscapes, as two rows of four dramatic birds’-eye panoramas on one sheet of paper, depicting Karikachi Pass in Kokkaido, Towada Lake in Aomori/Akita, Nikko Kegon Waterfall in Tochigi, Kamikochi Valley in Nagano, the Kiso River in Gifu and Aichi, Muroto Cape in Kochi, Mount Unzen in Nagasaki and Beppu in Oita. Targeting middle-class women readers, the insert was published in the magazine Shufu no Tomo (Housewife’s Companion) in August 1930.

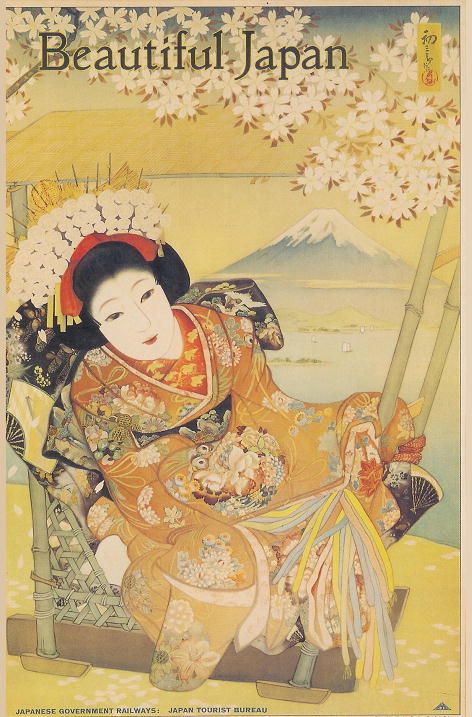

Clearly Yoshida’s work was instrumental in identifying both destinations and travel routes for domestic tourists—literally putting many previously unknown attractions “on the map.” Yoshida is also credited with helping to brand Japan through his widely-distributed and iconic “Beautiful Japan” posters produced during the 1930s for the International Tourism Bureau.

**

Yoshida’s work remained ubiquitous in Japan up until the outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, when the military decided that his detailed overviews of strategically essential ports and cities threatened national security. His maps were banned; original paintings representing years of painstaking effort were confiscated and burned. His talents were however recognized; he was then deployed as a war artist to map newly-added territories of the empire.

At the close of the Pacific War, in 1945, Yoshida personally experienced an air raid in Kumamoto, on the same day as the nuclear strike on Nagasaki. From May 1946, he spent five months traversing the ruins of Hiroshima, interviewing around 300 A-bomb survivors before creating chillingly powerful magazine illustrations of the tragedy—eight images plus cover—including an overview of the city’s location in the archipelago, a tranquil morning view moments before the attack, then under the fearsome mushroom cloud, and in the hellish evening of the same day. These images were also published in English-language format during the Occupation, to convey the horror of the Hiroshima bombing to the outside world; the publisher went bankrupt in 1953 and copies are now exceedingly rare.

This project, documenting both the atomic bomb’s destruction of a beloved landscape, and its devastating impact on mostly civilian inhabitants, was deeply meaningful for Yoshida. Unfortunately, after his extended sojourn in Hiroshima he developed some symptoms of radiation poisoning that are said to have resurfaced before his death in 1955, at the age of 71.

**

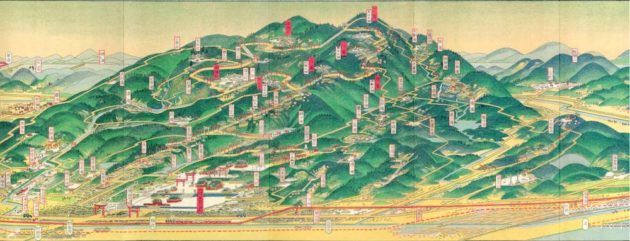

Not surprisingly, Yoshida’s trademark “picturesque maps” have remained highly popular over the years, and can now be seen as imaginative antecedents of views currently seen on Google Maps 3-D mode, and state-of-the-art dashboard-mounted satellite navigation systems. Local governments all over Japan proudly exhibit enlargements of his maps, as valuable historical resources showcasing their towns and stimulating local nostalgia for an archetypal historical Japan. Amazingly, a small shop on the skyline path above Kyoto’s Fushimi-inari Grand Shrine still sells (for just 100 yen) a miniature version of his 1928 panorama of the sacred mountain.

Even now, Yoshida’s work is still contributing to building and strengthening local identity, and encouraging present-day domestic tourism, based on the unique features and noteworthy attractions of locations all over the Japanese archipelago.

Featured in digital issue KJ99: Travel, Revisited

Ken Rodgers, managing editor of KJ, has been fascinated by maps ever since being nominated by his uncle Bill as a full member of the National Geographic Society, at eight years of age, in 1960.

Header image: Nihon meisho no e (A Picture of the FamousPlaces of Japan), Kuwagata Eisei, 1804