A Portrait of the Author of The Pillow Book, by David Greer

[A] thousand years ago a lady-in-waiting in the imperial court at Heian Kyo (modern-day Kyoto) dipped her brush into the well of her inkstone and watched the bristles swell with ink. She lowered the brush onto the paper spread in front of her and moved her hand rapidly:

Haru wa akebono . . . In spring, the dawn. The sky, dyed in morning light, slowly brightens and purple clouds stretch across the mountains. . . .

She guided the brush up and down the page:

Natsu wa yoru . . . In summer, the night. I need not write of the nights lit by the moon, but of the moonless nights, the fireflies’ lights crossing in the darkness. . . .

A bristle worked itself loose. She perched it onto the left edge of the inkstone and continued:

A bristle worked itself loose. She perched it onto the left edge of the inkstone and continued:

Aki wa yugure . . . In autumn, the evening. The setting sun burnishes the edges of the mountains and the birds fly home. . . . A trembling line of wild geese flies into the distance and disappears. . . .

“Shonagon,” a voice called. She lifted her hand and looked toward the corridor. After she glanced at what she had written, she laid her brush lengthwise on the inkstone. When she stood up the brush shifted slightly, so she bent down and gently tapped it. Satisfied that the barrel of the brush was aligned with the inkstone’s left edge, she left the room.

This is the beginning of The Pillow Book, a pastiche of idiosyncratic lists, diary entries, and reminiscences — one of Japan’s earliest prose masterpieces. Its author, Sei Shonagon, probably wrote this in 1000, the same year a scribe in England scratched runes into a manuscript of Beowulf.

Shonagon imbued these opening lines with mono no awaré: beauty is precious because it is brief. Mono no awaré, the heritage of the Heian Period (794-1192), became a uniquely Japanese aesthetic. A preference for, Joseph Campbell writes, “the unsymmetrical [that] suggests movement; the purposely unfinished [that] leaves a vacuum into which the imagination of the beholder can pour.” In The Pillow Book‘s opening lines, Shonagon puts things in motion to remind us they will not last: the clouds stretch only to disappear; the fireflies’ paths do not meet again; the geese fly into the setting sun and darkness descends. Her sentences don’t end so much as they scatter, like cherry blossoms tugged off branches in the wind — a favorite simile of writers at the time — mono no awaré.

But frankly, mono no awaré was pop culture during the Heian period. Shonagon’s contemporary, Murasaki Shikibu, uses the word awaré over a thousand times in The Tale of Genji (granted, it’s a long novel) and, while the Japanese pride themselves on their ability to quote the beginning of The Pillow Book in Heian Japanese (they have to memorize it in junior high), few Japanese have read the book far enough to know that Shonagon does something else within its pages that reminds us all of our humanity, regardless of our time, culture, or language.

She complains. She gloats. She finds fault with others. And when she does, the millennium separating her from us vanishes: “Just as a woman is about to tell me something really interesting,” she writes in her list of Things That Irritate Me, “and I’m sitting there just dying to hear it, her baby starts crying.” “I know I shouldn’t think this way, and I know I’ll be punished for it,” she writes in her list of Things That Make Me Happy, “but I just love it when bad things happen to people I can’t stand.” “Ugly people,” she starts off her list of Things That Don’t Have Any Redeeming Qualities, “with disagreeable personalities.”

The Pillow Book ends in tragedy. Teishi, the young empress whom Shonagon serves, gets in the way of her uncle, the ambitious Fujiwara Michinaga. Michinaga’s insatiable desire for power drives him to break the “one emperor-one empress” tradition that weathered the reigns of sixty-six monarchs. He forces the emperor to recognize a second empress, Michinaga’s eleven-year-old daughter. Teishi, at twenty-four, pregnant with the child of the emperor who abandons her, her father dead and her brother powerless to help, faces Michinaga alone. When it’s over, Shonagon leaves the court and disappears.

The city of Kyoto erected a monument to Shonagon here: a large rock with one of her poems, a tanka, inscribed in its side. Legend has it that Shonagon came here after Michinaga triumphed. I believe it: Shonagon’s father’s house was here (he died in 990), and Teishi’s grave is a ten-minute walk away. Shonagon loved Teishi. I can see her walking up that hill to tend to her empress’s grave.

Shonagon’s grave may be here also. Nobody knows. Nobody knows her name either. “Shonagon” was an imperial rank, “minor counselor.” Someone later added the name “Sei,” which refers to her father’s name, to distinguish her from the other shonagons in her world. The only things we know for sure about her are what she wrote in The Pillow Book.

The characters etched in this rock, though, explain how a nameless woman could write one of her country’s first prose classics. In Shonagon’s time, a tanka was a thirty-one character verse form arranged in a 5-7-5-7-7 pattern. “Poetry,” Shelley writes, “lifts the veil from the hidden beauty of the world.” This wasn’t a metaphor in Heian culture. The Heian noblewoman lived behind a kicho, a moveable frame large enough to conceal her; curtains hung from its top rail. (The best place for the kicho, Shonagon writes, is near the veranda, where she can hear the world file past the curtains blocking her view.) Since the Heian noblewoman wasn’t allowed to show herself and, until marriage, was forbidden to speak with men outside the family, the only way Heian aristocrats could pine for each other was through tanka. Servants, clutching poems penned in their master’s and mistress’s hands, scurried back and forth among the aristocrats’ mansions, shouting, presumably, “You’ve got tanka!”

Shonagon writes The Pillow Book in the same characters lovers wrote their tanka in, hiragana. Hiragana was Japanese, a derivative of kanji, the intricate characters of the greatest civilization on earth, Tang Dynasty China. Easily written with a flick of the brush, hiragana and the brief tanka clicked — mono no awaré.

Heian noblemen sniffed at hiragana, though. They called it onnadé, the women’s hand. Good for poetry and love letters, maybe; but for the Heian man to write “something serious” in hiragana was as unseemly, notes Arthur Waley (Shonagon’s earliest translator into English), “as a [modern-day] London clubman [walking] down Bond Street in skirts.” Everybody knew that real men wrote the real literature in Chinese, in kanji. Men discouraged women from learning Chinese characters; it just wasn’t feminine. So, when women lifted their writing brushes, they wrote in hiragana.

And so Shonagon writes The Pillow Book in Japanese, the women’s hand. “Never intending,” she writes on its final page, “these notes to be seen, I simply wrote to while away those long hours when I had nothing better to do.”

“When I first went into waiting I was dreadfully embarrassed. I had no idea what to do and felt so helpless I was always on the verge of tears. I was so self-conscious that when I attended Her Majesty I cowered behind my kicho. One night Her Majesty brought out some pictures to show me, but I couldn’t bring myself to take them. I was too embarrassed to show my hands beneath the curtains. . . .”

Shonagon, married and divorced before she is twenty-five, has three choices: find another man, enter a Buddhist convent, or serve at court.

When Shonagon arrives at the palace, Teishi, fourteen, is an imperial consort, a concubine. Teishi’s future husband, the emperor, is ten. Teishi was born to be empress. Her father, the imperial regent Fujiwara Michitaka, like generations of Fujiwara before him, depends on his daughter to control the emperor and the power of the throne. The emperor reigns, but the Fujiwara regent rules. For every emperor a Fujiwara daughter is born or, like Teishi, is already waiting. She becomes empress and gives birth to the next emperor, who is raised in a Fujiwara mansion. And so it goes: the regent “advises” the emperor. If the emperor is recalcitrant, the regent asks his sister, the emperor’s mother, for help.

When Teishi’s father dies her position becomes precarious. Michinaga wants to shift power to his side of the family. His daughter must become empress.

Shonagon doesn’t write of these things, however. She, and the other women Teishi selected for her coterie, do what aristocrats did to pass the time. They write tanka, go on excursions and pilgrimages (more for something to do than spiritual advancement), and take lovers.

Shonagon writes extensively about her affairs. These boudoir scenes, though, disappoint that reader who, titillated by The Pillow Book‘s title, hopes to find thousand-year-old erotica. (The most sensuous passage I found describes a solitary autumn afternoon: “I love to slide a silk robe over my face and take a nap,” she writes, “breathing through the filmy scent of sweat.”) Few of Shonagon’s lovers please her, though, and most find themselves included in her list of Things That Irritate Me. They snore, and stumble around in the darkness the morning after, looking for the Heian equivalent of their car keys.

The Pillow Book‘s title comes from the Heian aristocrats’ habit of keeping notepaper near their pillows, makura. Since Shonagon calls her work in progress soshi, “random notes,” the Japanese refer to her collected essays as Makura no Soshi (Random Notes of the Pillow), a title she probably never used herself.

The Empress Teishi, from their first meeting, shows a special affection for the older, and vastly more experienced, Shonagon. Throughout The Pillow Book Teishi gently chides Shonagon for her excesses and, while Shonagon never admits it, the reader readily sees that Shonagon aspires to be like Teishi: considerate, delicate, gentle. Teishi becomes the center of Shonagon’s life for the next ten years, the only person to whom Shonagon shows tenderness. Shonagon writes as if her empress were ethereal: “My eyes were opened to a beauty I didn’t know existed in this world.” Teishi may well have been divine, Shonagon’s acerbic brush wouldn’t have spared her if she weren’t, and the portrait Shonagon draws of her fragile empress makes Teishi’s tragedy all the more poignant.

A tragedy that reaches out for, but does not engulf, Shonagon. While what became of Shonagon remains a mystery, the pages she leaves behind indicate a personality bent on survival: “When I come into the room to serve Her Majesty and see the other women have already crowded around her, I sit next to a column apart from them. Her Majesty sees me and calls. I love it when the others make way for me when I go to sit next to her.”

Shinto shrines are fronted by at least one torii gate: a curved top beam, tips straining toward the sky, atop a cross-beam held aloft by two inwardly slanting columns. The main shrine at Fushimi Inari has thousands — lined up one after another, all bright vermilion, straddling the paths that wind up the mountain to the smaller shrines on its peak. With the sun high in the sky, the torii glow as if they were just forged, riven of their casts, and left fuming on the sides of this mountain.

Shonagon came here on a pilgrimage. In her list, People That I Envy, she relates an incident that occurred close to the spot I stand now:

Though I started at dawn, by mid-morning the heat was rising and I was only halfway up. I was hot, tired, and felt thoroughly sorry for myself. Why should I go through all this trouble, I thought, when plenty of people don’t go on pilgrimages at all? I sat down and felt so frustrated I actually started to cry. Just then a woman, who looked about thirty or so, came down from the upper shrine. “I’m going up seven times today,” she said to the people on the path. “This is my third time; shouldn’t have any trouble with the last four. Probably be down the mountain by two o’clock.” . . . How I wished I could be a woman like her!

How glad I am she wasn’t. Shonagon writes 164 lists. Many are just that: lists of nouns, without commentary. The short ones move like e.e. cummings poems — Things That Pass by Rapidly: “A boat under full sail. Age. Spring. Summer. Fall. Winter.” The titles alone are worth the price of admission. Things That were Good in the Past But are Useless Now (“a dead pine tree smothered in wisteria”; “a man, amorous in youth, enfeebled by age”); Things That Look Hot and Uncomfortable (“fat people with hair plastered on their foreheads”; “a coppersmith at his forge during the summer”); Scruffy Things (“the back side of a piece of embroidery”; “the inside of a cat’s ear”); Things That are the Reverse of the Other (“summer and winter”; “the feeling I have seeing a man I once loved but now don’t”); Things That are Especially Rare (“A father-in-law who praises his son-in-law”); Things That Make Me Happy (“I’m delighted when I find that, after putting the scraps together, I can read a letter someone threw away.”).

Shonagon likes things to be a certain way. Young people, babies, and high-ranking government officials should be chubby; if they are not, they look “nervous.” “A priest should be handsome,” she asserts, “to make the worthiness of his sermon easily appreciable.” An unattractive priest may, by her reasoning, cause his congregation to sin.

She has her prejudices. The nightingale’s song, she writes in her list, Birds, is celebrated in verse, as well it should be; but even when nightingales flit from tree to tree in the palace grounds they do not sing, and this is “dreadfully boring.” “Yet,” she writes, “when I leave the palace and travel through ‘that part of town’ I see them perched on the branches of the most nondescript plum trees warbling away among the commonest of houses.” Similarly, in her list, Things That Don’t Suit One Another, she notes that nothing goes better with rooftops, cloaked in freshly fallen snow, than pale blue moonlight; when this effect is reproduced on the rooftops of the “commoners” houses,” though, it is “most unseemly.”

She writes in a style the Japanese call zuihitsu, “the brush moving with the mind.”The result is often tangled threads of thought — the droll competing with the tragic. “Dogs that howl in the daytime” heads off her list of Things That Depress Me, followed by “people who wear clothing out of season.” Then, starkly, “a room prepared for childbirth in which the baby died” precedes “a charcoal brazier [used to heat the drafty rooms] in which coals won’t catch fire.” She follows that with “carriage drivers who beat their oxen,” before she frowns at a professor’s wife “who gives birth to girl after girl, as if the hapless mother doesn’t know that a woman can never aspire to a position in academia.

The way she describes these things, and where she starts and stops, is delightful. The ox she evokes in her list of Things That Can be Seen Comfortably is not remarkable in its final appearance, but in the fluid order she summons its oxen characteristics to the tip of her brush, as if she is squeezing the ideal ox head-first out of a tube, and its damp tail just flicked out: “An ox should have a small forehead,î she writes, “tinged with white hair. Its lower belly, the tips of its legs, and the point of its tail should also be white.”

Many lists read as if she took up her brush one morning a thousand years ago, but just laid it down — the ink still glistening on the page. Things That Make Me Fondly Recall the Past: “Dried hollyhock leaves from the Kamo festival. Dolls I played with as a child. . . . On a rainy day with nothing better to do I go through old things — I find a love letter that years ago moved me deeply. Last year’s fan. A night bathed in moonlight. . . .”

We feel a nagging deja vu, as if she wrote the stuff of our own memories. Lovely Things: “A baby thumps across the floor on her hands and knees — something tiny catches her eye. She charges over to it and picks it up, marveling at her find. Then she shows it to each adult in the room, her expression asking them to share in her wonder.”

And the lists where her brush moves into art. Looking out from her gissha, an ox-drawn carriage, as it lumbers across a river under a full moon, “the ox’s hooves break the surface, the water shatters like crystal.” On a summer excursion, in the close air of her gissha (“watching the lotuses floating in the pond,” she writes, “was my only relief from the heat”), she watches noblemen move from a mansion’s dark interior to its wide, sunlit veranda. Their linen robes, somber in the shade, catch the light — gauzy purples layered on yellows, whites, and pale grays. Against these colors the noblemen open their red paper fans “like a field of pinks coming into bloom.”

She invariably ends these reveries with her trademark, an insistence that the reader understand who wields her brush: “Early dawn in the palace garden after a night of rain. The dew on the chrysanthemums sparkles in the morning light. Beads of water cling to rain-tattered spider webs like pearls poised on strands of silk. The sun rises, and the hagi’s slender branches, trembling under the weight of the dew, suddenly spring up — mist flashes in the light. I’ve asked, but none of the other women finds this remarkable. Knowing it is something only I enjoy makes it all the more delightful.”

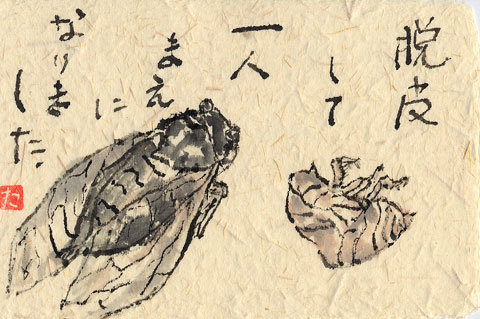

I walk out the main building at the mountain temple of Hasedera onto a veranda that overhangs a steep slope, bristling with cedars. It is late afternoon, and when I lean on the railing the wood is cool under my forearms. A lone cicada whines somewhere far below.  I look down into the narrow valley. A small village hugs the banks of a listless creek that, when Shonagon came here, was a swollen river. She wrote of the terror she felt working her way up this slope, gripping the rails of a log staircase, the roar of the water in her ears. Other nameless women authors (all ladies-in-waiting) came here too. Murasaki Shikibu served in the court of Michinaga’s daughter, the child who took Teishi’s place. Murasaki writes The Tale of Genji (the world’s first “modern novel”) in onnadé. Another, “the daughter of Takasue,” as she is known, describes the trip to Hasedera from Kyoto in her Sarashina Diary: day after day swaying in her gissha, fearful of bandits. She also writes in onnadé. Like The Pillow Book, these books are still in print a millennium later. It takes a while for Japanese men to catch up. They write in Chinese, in kanji, for another two centuries.

I look down into the narrow valley. A small village hugs the banks of a listless creek that, when Shonagon came here, was a swollen river. She wrote of the terror she felt working her way up this slope, gripping the rails of a log staircase, the roar of the water in her ears. Other nameless women authors (all ladies-in-waiting) came here too. Murasaki Shikibu served in the court of Michinaga’s daughter, the child who took Teishi’s place. Murasaki writes The Tale of Genji (the world’s first “modern novel”) in onnadé. Another, “the daughter of Takasue,” as she is known, describes the trip to Hasedera from Kyoto in her Sarashina Diary: day after day swaying in her gissha, fearful of bandits. She also writes in onnadé. Like The Pillow Book, these books are still in print a millennium later. It takes a while for Japanese men to catch up. They write in Chinese, in kanji, for another two centuries.

The logs are gone now. The stone staircase leading down to the main gate was first built in 1039, years after Shonagon is believed to have died. Still, the ridges across the valley haven’t changed in these thousand years, and the forest that covers the valley floor hides most of the village. A wind comes down the mountain and sighs through the cedars, the sound of a river heard faraway. Behind my closed eyes I hear four gissha crunch over the stones to the riverbank below. The attendants reach for the harnesses as the oxen, smelling the water, bellow and strain at their traces, hooves digging holes in the gravel. Shonagon gets out first, of course. She walks away from the river and stretches. Her companions call to her (bring friends on long pilgrimages, Shonagon advises; otherwise, conversation is limited to servants), their voices barely audible over the sound of the rushing water. Shonagon turns, smiles, and looks up at the temple. A cloud moves away from the sun and she shields her eyes, the white of her hand flashes against the deep blue shadows under the trees.

Teishi’s father dies in 995. Another of her uncles becomes regent, but dies a week later. In 996, Teishi’s older brother, the regent-apparent, is implicated in a plot contrived by Michinaga and banished. That same year Teishi gives birth to a girl. Three years later, the year Teishi gives the emperor a son, Michinaga’s daughter, Shoshi, comes to court as a concubine. Michinaga whispers to his sister, the emperor’s mother. The emperor reluctantly agrees. Shoshi becomes the second empress in 1000. Teishi, heavy with child, is moved out of the palace. She dies in childbirth. The baby, a girl, lives. Shonagon vanishes. Perhaps she returns to her father’s house. Teishi will be laid to rest nearby. The Buddhist temple Sennyuji stands there now.

The great Michinaga came to Hasedera in 1024. He must have struggled up the log staircase. I like to think he tripped, maybe barked his shins.

A thousand years ago Shonagon came back to her room and knelt at her table. She rolled the tip of her brush in the inkstone until the ink bled through the bristles. Then she wrote:

Fuyu wa tsutomete . . . In winter, the early morning . . . waking to see everything glazed in frost. . . . Servants hustle from room to room, bringing coal and stirring up the drowsy embers in the braziers.

She lifted her brush and dabbed at a bristle that had dried on the inkstone’s left edge. The bristle didn’t budge. She ignored it, and brought the tip of her brush down to the paper. “But it gets warmer as the sun rises in the sky,” she wrote, glancing at the stubborn bristle, “and the servants stop tending the braziers. The ashes snuff out the last of the embers, and this is dreadfully boring.”

Note:

All quotes from The Pillow Book in this essay were translated by David Greer.

Readers interested in Shonagon can find The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon, (Columbia University Press) translated and edited by Ivan Morris. In their well-known translations, Morris, Sansom, and Waley used Japanese readings of the Chinese characters to refer to the Empress Teishi as “Sadako,” and Michinaga’s daughter, Shoshi (for whom Murasaki Shikibu, the author of The Tale of Genji, served) as “Akiko.” The author of this article used the Chinese reading of these names following the tradition of Japanese scholars (and Richard Bowring, in his 1996 translation of Murasaki’s diary).