After the dig, Savitsky stayed on in the nearby town of Nukus, somehow convincing the local authorities not only that they needed an art museum, but that he was the man to run it. This took some time, but in 1966 Savitsky was appointed founding director of the Nukus Museum of Arts. He was a completely unknown curator in a museum so far past the back of beyond that even the government of the Uzbek SSR, normally into everyone’s business, scarcely noted its existence.

The museum’s obscurity, and Savitsky’s own lack of social standing or professional reputation in the art world, meant that no one in authority thought to look at what he was doing. Savitsky took the opportunity to quietly buy up the works of Russian painters who had been killed, sent to the gulags in Siberia, or otherwise fallen foul of the State. He acquired everything he could get his hands on, despite the fact that such works were officially banned, and when the public funds he used, somewhat ironically, to finance his acquisitions ran out, he bartered with artists and dealers, or made promises of future payment. Over the course of 10 to 15 years, he amassed one of the world’s greatest collections of Russian avant-garde art, and when the collection came to light after his death and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the works were finally put on public display and gained international acclaim. The Nukus Museum of Arts or, to give it its full modern title, “The Karakalpakstan State Museum of Art named after I.V. Savitsky,” is now fondly known amongst Russian art lovers as the Museum of Forbidden Art.

On behalf of his museum in Nukus, Savitsky collected some 90,000 items, an extraordinary achievement. The items include thousands of artifacts including textiles and jewellery from ancient Khorezm; works of anthropological interest by 20th century Uzbek and Karakalpak artists; and, of course, the 40,000 graphics, paintings and sculptures for which his collection is renowned. Only a fraction of these masterpieces can be displayed at any one time. Western art critics including C. Douglas, J. Bowlt, and A. Flaker have suggested not only that Savitsky’s collection is the most significant collection of Russian avant-garde works in the world, but that it should form the basis on which any reconsideration of Russian and Soviet art history is made. It is, in short, one of the première art institutions in Asia—and yet it is almost unknown.

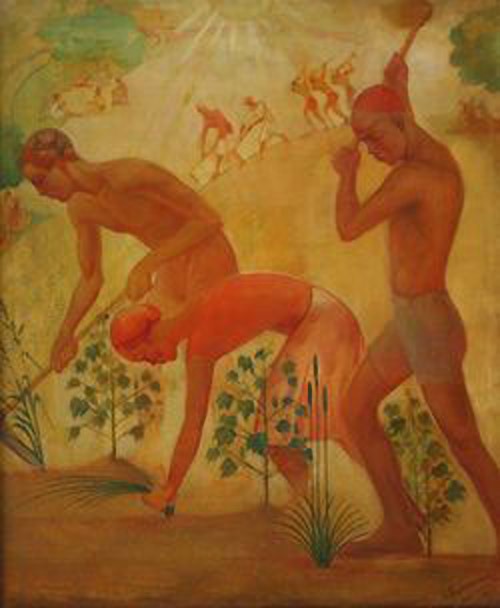

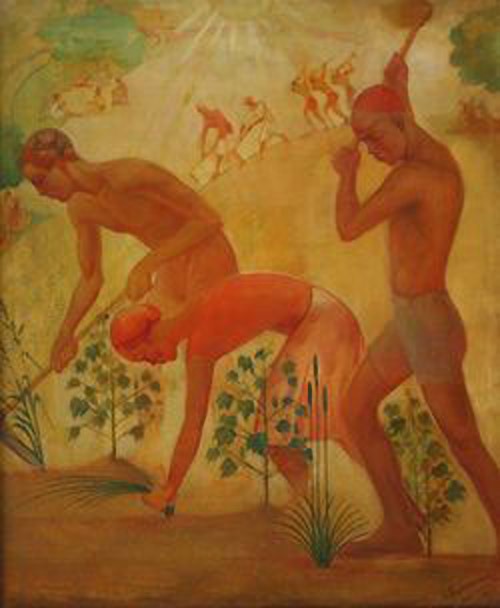

The Russian avant-garde movement swept across Russia and her imperial possessions (including Uzbekistan) in the late 19th century and remained influential in the modern art world until at least the 1930s. It includes a number of interconnected artistic styles that flourished in Western Europe as well as in Russia, such as Constructivism, Realism, variations of Futurism, Neo-primitivism, and Zaum, and though we think of it primarily in terms of painters and designers, there were also avant-garde architects, composers, writers, and film makers. The 1922 Shukhov Tower, an iconic structure on the Moscow skyline and one of the most striking images in the Royal Academy of Arts’ 2011 exhibition, Building The Revolution, is perhaps the most famous example of a Russian avant-garde structure.

The movement reached its height between the Russian Revolution of 1917 and 1932. This was a period of previously unknown creative freedom, when all manner of styles and mediums—from oil paints to textiles to ceramics—became propaganda channels promoting the utopian ideals of the new Soviet society. This all came to an abrupt and violent halt in April 1932, however, when a decree entitled On Restructuring Literary and Artistic Organisations was issued. It ushered in a new, state-sponsored art form: Social Realism.

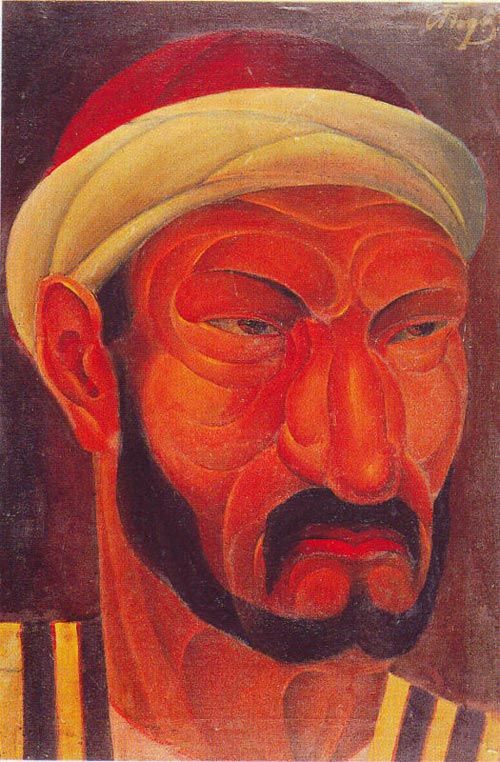

Socialist Realism was intended to further the aims of socialism and communism. It glorified the working class and their struggle, whereas avant-garde was now seen as something simultaneously decadent and subversive, an import from the capitalist West. It was hard to deny the influence of French artists in particular: the so-called Jack of Diamonds group, which included I. Mashkov, A. Lentulov, P. Konchalovskiy, and A. Kuprin, also referred to themselves as Moscow Cézannists on account of their use of Cézanne’s graphic techniques, tinged with Neo-primitivism; S. Diaghilev had refused to return to Russia after the Revolution, so enamoured was he with Paris; and it had been a great period of physical movement and artistic exchange between the artists of Russia and France.

Any work that did not comply with the decree was dismissed as Formalism, and so the leading figures of the Russian avant-garde movement fell almost overnight from grace. The anti-Cubist and Futurist P. Filonov starved to death in 1941 after the Soviet government banned him from exhibiting his work; A. Fonvizin, a Formalist, was exiled to Kazakhstan in 1943; the Constructivist G. Klutsis was executed on Stalin’s orders shortly after his arrest in 1938; and the same year A. Drevin, a proponent of brutal primitivism, was arrested and executed by the NKVD. Other artists such as W. Kandinsky, M. Chagall, and D. Burliuk (the father of Russian Futurism) survived and continued to work because they were able to emigrate from the Soviet Union to western Europe and the U.S., or because they changed their style and produced propaganda paintings in the new Socialist Realist style.

Savitsky bought up the banned paintings of these famous fallen artists, and thousands more works by their lesser-known contemporaries who had been spared the worst excesses of the Soviet regime but nevertheless could not continue working in their previous styles.

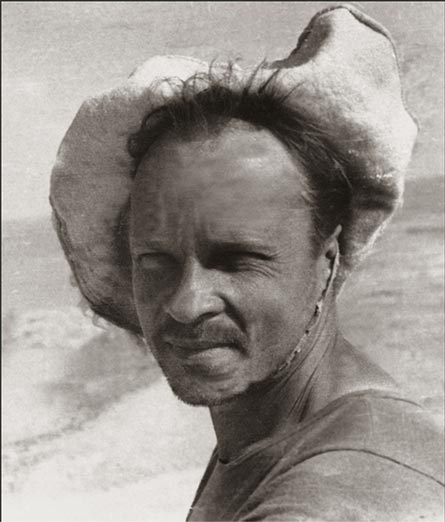

We don’t know exactly where Savitsky’s interest in these kinds of paintings came from, what it was that drove him to risk being denounced as an enemy of the people while seeking out proscribed painters and their heirs, collecting their works and preserving them in his collection. Though he was a Russian, Savitsky was born in Kiev in 1915, and as his relatively wealthy parents came under suspicion during the October Revolution, it is unlikely young Savitsky would have had access to Moscow’s intellectual and artistic elite: his family was too busy maintaining a low profile, which was also the reason he trained as an electrician—a good member of the proletariat—rather than anything more controversial.

By the time he made it to Moscow as a student at the Surikov Institute, the heyday of Russian avant-garde art was long gone. In fact, the first catalyst of his interest most likely came not in Russia at all, but when he arrived in Samarkand, Uzbekistan in 1942, evacuated there with his fellow students from the institute. Here he met R. Falk, a founding member of the Jack of Diamonds group, who taught painting at the Uzbek Art College from 1941 to 1943. Falk believed that the subject was not the most important aspect of a painting, but rather the interplay of constructive forms and emotional expression through use of colour. Falk was an inspiration teacher and the doors of his studio were always open to those who wanted to learn. Savitsky and Falk became friends, and it would have been during this period in his life that Savitsky both learned to paint and to appreciate contemporary art. His love of art, and of Central Asia, would dominate his life right up until his death in 1984.

Savitsky returned to Uzbekistan after the war, in 1950, first for an archaeological dig (his first encounter with Karakalpakstan) and then working for the Karakalpak branch of the Uzbekistan Academy of Sciences. He took it upon himself to train local artists there, and continued to make his own paintings. When he was finally granted permission to open his museum, his priority for acquisitions were not Russian avant-garde artworks, but rather archaeological finds that would explain to people the rich history of Khorezm and its fortresses, and also paintings made in Tashkent and Moscow in the 1920s and 1930s that might inspire his Karakalpak protégés to further develop their own artistic talents.

Savitsky collected works by artists linked to Central Asia, as well as those by the founders of the Uzbek School. This inevitably included some avant-garde works of art, as, no longer popular and largely forgotten, they would have been relatively cheap and easy to come by in Tashkent. He was also trying to build up a rounded collection that reflected all the styles produced by Uzbek artists (and Russian artists painting in Uzbekistan) during that time.

One of Savitsky’s most important, and controversial, acquisitions during this period was The Bull (Fascism is Advancing) by Y. Lysenko, a Russian who came to lived in Tashkent in 1918 and participated in the first Republican Exhibition of Fine Art Workers of Uzbekistan in the 1930s. Lysenko was arrested in 1935, a short while after he made the painting, and sent to a mental asylum. The painting, the authorities said, was anti-Soviet.

Forty years later, the same painting riled the authorities again, but this time Savitsky’s neck was on the line. He had hung the painting on the wall of the museum, at great personal risk, where it was seen by a party of Communist officials. Although the subtitle of the painting is Fascism is Advancing, it is in fact not entirely clear which political system the painter was denouncing, and the officials ordered the painting be taken down. Savitsky obeyed the order, but rehung the work as soon as they had left.

Savitsky was inspired by the Uzbek avant-garde works he had collected, but at the same time was deeply troubled by the negative impact of Soviet cultural policies introduced under Stalin, the ongoing censorship of art. Deciding he could not allow the art of a generation to just disappear, he deliberately began to collect works that no one else would, the paintings of the Russian avant-garde movement. He travelled back and forth to Moscow and other cities in the Soviet Union by train, packing his luggage with illicit canvases. As no one else recognised their true value, or would risk being seen paying for them, he acquired most of the paintings for a fraction of their actual worth. He used both his own modest funds and those of the museums, lying about what he bought when necessary.

Perhaps Savitsky’s most daring (and certainly dangerous) purchase was a series of drawings of a Soviet labour camp (a gulag) made by N. Borovaya whilst she was imprisoned for seven years in the notorious Temnikov Camp. The simple black and white sketches were smuggled out of the camp by a visitor, and around 30 years later, Savitsky heard they were up for sale. He convinced his superiors that the scenes in fact depicted a Nazi concentration camp, used official funds to make the purchase, and was no doubt proud of both tricking the system and, most importantly, saving the precious drawings for posterity.

Today, 30 years after Savitsky’s death, his collection and the museum are in limbo. Although they are passionately defended by the museum’s present director, M. Babanazarova, and a four-year building programme began in 2013, at the same time funding is almost non-existent, putting irreplaceable paintings at risk.

Only two percent of the art works in the collection are currently on display, and those in storage are simply piled up in boxes and on shelves where they can be easily damaged by dirt and sunlight. There is no budget for conservation, and the museum’s website includes a wish list for donations of basic items such as a printer, hygrometers, and anti-moth strips. It will be a tragedy indeed if having survived Stalin’s purges and a subsequent disappearance into oblivion, and finally having risen to a position of international acclaim, the finest works of the Russian avant-garde movement are lost, this time forever, due to lack of funds.

SOPHIE IBBOTSON AND MAX LOVELL-HOARE run Maximum Exposure Productions, a consultancy company specialising in emerging markets and post-conflict zones. They have had an office in Central Asia since 2008 and have worked with government and private-sector clients in the region. Sophie and Max are the authors of five Bradt Travel Guides, including Uzbekistan, and have also written for Newsweek, the Sunday Telegraph, and the Financial Times.

Images courtesy of the Savitsky Collection (http://www.savitskycollection.org/)

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013