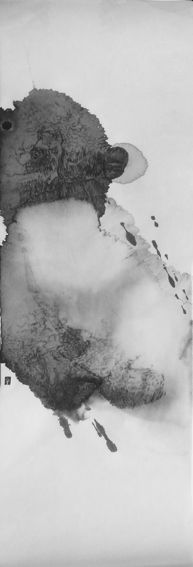

[C]alligraphy and ink painting are two of the pillars of East Asian visual arts. Both use the same materials, both have a monochrome aesthetic. For calligraphy, it is the line work and its relation to the white space which is its hallmark, for ink painting it is the brushwork itself, ‘the touch’ or ‘le tache,’ and the sumi gradations from deep black to the lightest of greys.

[C]alligraphy and ink painting are two of the pillars of East Asian visual arts. Both use the same materials, both have a monochrome aesthetic. For calligraphy, it is the line work and its relation to the white space which is its hallmark, for ink painting it is the brushwork itself, ‘the touch’ or ‘le tache,’ and the sumi gradations from deep black to the lightest of greys.

Professional calligraphers and ink painters practise years to master their art. Ink painting students at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing study 7 years, 4 as undergraduates and 3 in their chosen field – bird and flower, landscape or figure painting. It is no easy task to learn to control the materials, and even for those so well trained, the medium will remain essentially unpredictable, a characteristic seen as a plus. In Japan, artists exploit the chance element, loading brushes with sumi for splash or spreading effects. Sumi artist, Reiko Yoshida is typical when she says for her the control/chance ratio is 60:40 which she is happy with. For the beginning Westerner it may be frustrating as it seems impossible to repeat one-off successes, but it is also a delight, as unexpected effects abound.

The relationship between this medium and the artist is one of dialogue, there is a continual give and take, perhaps more than in any comparable Western medium. This means that while the artist is executing the artwork they must be totally at one with it, completely concentrated, brushing a line, placing marks, and is, at the same time, responding to what is given. At its core, this is a vibrantly alive relationship and it is very fragile, it can flop if the attention wanders. This aliveness is the heart of the sumi aesthetic, which has been documented throughout history by Chinese and Japanese art theorists. It is also one of the reasons the medium was and is used by Zen priests to manifest their presence in the present moment, their essence in the existential here and now.

The sumi line and mark is something of a paradox to the Westerner. Accustomed to drawing and painting as two distinct branches of art, sumi bridges both. Under-painting for full coloured paintings and sketching in the Western manner is part of the East Asian tradition, but the subtly gradated worlds created by Chinese ink painters in the Northern Song tradition, the strident black and white ideograms of Japanese Zen calligraphers or the whimsical figure paintings of the Japanese 18th Century literati indicate a medium with a wide expressive value, capable of a myriad of styles. The range of line work is immense: it can be a thin outline, either for filling in with colour or sumi washes; alternatively, used with the absorbent East Asian paper, it becomes a modulated brush stroke, charged with the energy of a Western brush or charcoal, but full of the softness and warmth characteristic of supple East Asian brushes. Lines brushed with diluted ink can be built up in masses, transparently revealing the layers of brush strokes and the halo of water around each. With darker ink the mass is opaque, no stroke visible. The sumi medium gives a range from thin, drier, exploratory lines and their build up in grainy compositions, to wetter, fuller lines which border on washes.

When I first started sumi painting – and I am sure this also holds true for many Westerners – East Asian art materials and the East Asian art canon itself felt impenetrable. The main route into this world is to learn the techniques and skills as they have been taught over generations in China or Japan. This involves years of dedicated practice and ensures the aesthetic as well as the techniques are kept intact. For a Westerner, or for those who have lived in a variety of cultures, this approach is not necessarily appropriate for a contemporary artform. I remember feeling strongly that I wanted to use sumi for my own vision, based on my life growing up in the UK and then as a foreigner here in Japan.

When I first started sumi painting – and I am sure this also holds true for many Westerners – East Asian art materials and the East Asian art canon itself felt impenetrable. The main route into this world is to learn the techniques and skills as they have been taught over generations in China or Japan. This involves years of dedicated practice and ensures the aesthetic as well as the techniques are kept intact. For a Westerner, or for those who have lived in a variety of cultures, this approach is not necessarily appropriate for a contemporary artform. I remember feeling strongly that I wanted to use sumi for my own vision, based on my life growing up in the UK and then as a foreigner here in Japan.

Over the years, I have forged another route. This involves a direct involvement with the materials, by-passing as far as possible the cultural prism through which their use has filtered. If we understand the principles which underlie the way the materials behave and learn some basic techniques which we can adapt for our own purposes, there is no fundamental reason we should follow the ways the medium has been used in the past. By exploring the materials thoroughly and finding ways that suit our art needs we can make the medium our own, and it need not feel alien.

For the past few years I have held Sumi workshops with various groups in the UK : professional artists and calligraphers, art students and children. Essentially the workshop is a time to experiment and play around with the sumi, to let go and to see what happens. The sense of liberation among participants is almost palpable, there are no expectations, no ‘shoulds,’ no senses of inferiority, the baseline for everyone is the same. (“You go into a different space, don’t you?” commented one of the participants on a Sumi workshop I held in Sunderland Winter 2006). By the end of the afternoon everyone has produced something new, and experienced a medium which behaves in a very different way from those they are used to, and which in itself is very unpredictable. In all the workshops there is an atmosphere of quiet concentration and relaxation.

In my artwork I relate directly to the art materials themselves; I also encourage participants in the workshops to do so. The materials are, after all, made up of universally available components – sumi from soot and animal glue, paper from various tree fibres, brushes from hairs from animals we are familiar with in the West. There is nothing essentially mysterious or inaccessible about them. I hope that participants are also able to feel they can use these materials without feeling they have to be able to brush the perfect bamboo, or understand the poems in calligraphy texts. There are conceivably limitless ways in which this medium can be beautiful, engaging, compelling – ways which have yet to be discovered. It is a liberating and exciting medium, in which there are possibilities for the development of new and different styles.

In this digital age, we can still learn from working with our hands. Using the sumi medium we are pushed into an almost confrontational relationship with materials. We brush sumi on paper, the effect is immediate, and we respond. In its instantaneousness it is a medium of our times. Through holding the brush, touching the paper, grinding the sumi and enjoying its fragrance as it dissolves in the water we feed our sensibilities, our minds and our muse, we do “go into a different space.”

See also Michael Lambe’s review, here

Christine Flint-Sato is a British sumi ink artist based in Nara, Japan. An extensive interview with her, “A Sumi Journey,”appeared in KJ 79.

“The Nature and Experience of Sumi Arts” is an adapted excerpt from her Sumi Workbook, published in July, 2014.