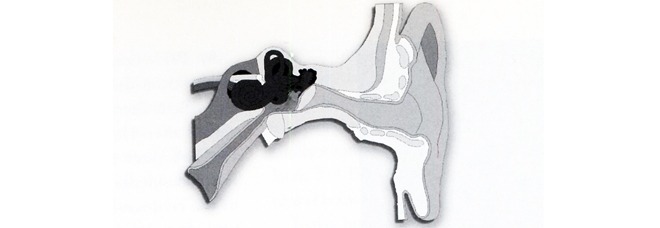

Otitis media: an inflammation in the middle ear that left untreated can result in permanent hearing loss.

—The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

[I]n the 1930s, when she met the man who would become Fujiko’s father, Ohtsuki Toako was twenty-seven and studying music at the Berlin University of the Arts. Born into a wealthy family in Osaka (her grandfather had invented Japan’s first industrial ink and made a fortune), Toako was beautiful: her hairstyle, a bob fashionable at the time, emphasized the graceful oval of her face, the classical line of her nose, and the taut outline of her lips. Except for her left eyebrow, which arched higher than its companion, nothing in her face hinted at the fiery temperament that smoldered behind her large, serene eyes.

Fujiko’s father was Fritz Gösta Georgii-Hemming. A Swede of Russian descent born into the aristocracy (his father was a legal counsel for the King of Sweden), Fritz had come to Germany to study at the Bauhaus. Tall, slender, with sandy brown hair and pale blue eyes, his long, delicate face ended in a fragile chin. He was working in the graphics department of a large movie studio in Berlin when, shortly after he turned twenty, he married Toako.

The couple settled in the city. Toako studied under the great Russian pianist Leonid Kreutzer, who, having emigrated after the Bloody Sunday Revolution of 1905, was now professor of piano at the Berlin University of the Arts. Fritz did well at the studio (he made the poster for the 1932 Marlene Dietrich film Shanghai Express , still used to advertise the picture today) and, three years after Fujiko was born, the couple was blessed with a boy, Wolf. At night, Fujiko snuggled in her bed, and Toako lulled her children to sleep with Chopin’s Nocturnes . The family looked forward to a bright future.

By 1933, however, the hammering of jackboots on the streets in Berlin echoed throughout Germany. On March 22, seven weeks after Hitler became chancellor, Dachau’s gates swung open. Days later, Jewish businesses were boycotted and Jews in the civil service and universities were fired. At night, the stadiums, glowing cauldrons against starless skies, rang with choruses praising the nascent thousand-year Reich.

Kreutzer, Jewish and out of work, acceded to the wishes of his frantically prescient Japanese pupils and went to Tokyo. Toako and Fritz too booked passage for Japan and said goodbye to the city they had loved and lost. Fujiko pressed her face between the ship’s railings and peered at the edge of the ocean, waiting for the land of her mother’s birth to rise from the waves.

Toako and Fritz’s marriage disintegrated shortly after the family settled in Tokyo’s Shibuya district. The domestic violence was so wrenching to watch that one of Toako’s relatives, Fujiko’s great-aunt Yoshino, took the children to stay with her. Fritz renewed his friendship with Kreutzer, now a professor at the Tokyo National University of the Fine Arts and Music; but Kreutzer’s companionship couldn’t compensate for Toako’s fury or his own unhappiness, and Fritz sought affection in the arms of another woman. But here, too, he was unsatisfied. His thoughts drifted back to the canals of his country’s watery capital, and one morning he decided to follow them. He boarded a ship and never came back.

The postcards came with the kanji OH TSUKI blocked in thick strokes, the only characters Fritz knew. “I’ll send for you when I get enough money,” he had written, perhaps meaning it. One afternoon the telephone rang. Toako’s face darkened and she thrust the phone at Fujiko: “He wants to talk to you.” Fujiko held the heavy black receiver with both hands and listened to her father’s voice scratch out his love for her. “Hang up!” Toako shouted, but Fujiko didn’t stop talking until her mother yanked the phone from her fingers.

Toako took Fujiko to Kreutzer’s recitals. Fujiko sat in the dark, enthralled with the bright lights on the stage, the man’s blurred fingers dancing over the keys, the sound that rippled from the shining black box spread before him, the applause and cries of “bravo!” When the notes from Liszt’s La Campanella pealed wave after wave into the air, the walls in the concert hall reverberated like the bells, la campanella , of the piece’s title, and Fujiko felt the music resonate in the chambers of her heart.

Her mother’s piano took up most of the living room. Fujiko squirmed up onto the stool. The notes spilled from the cabinet in curtains of sound that surprised and delighted her. From the next room, Toako heard what could be her reclamation. She had never professionally debuted, and with things the way they were, her talent would, at best, be spent in teaching. Through Fujiko, though, she might win the stardom that fate had denied her.

And so when Fujiko was six the lessons began: two hours long, two to three times a day. After Toako showed her how to decipher the squiggles on the scores, Fujiko was enchanted with the magic she could conjure, but she soon shriveled under her mother’s blistering criticism and the relentless repetition. Fujiko tore her clothes, screamed, locked herself in the bathroom, did anything to avoid touching those horrid keys. Her only respite came when Toako left the house to teach. Aunt Yoshino came to look after the children. Fujiko would dig into the pile of scores and pull out the music she loved, the pieces her mother wouldn’t allow her to play, Chopin’s Preludes , and in the harmonies Fujiko heard wind scurrying over the Polish steppes, burnished leaves swirling through forests of white birch, clear streams gurgling beneath blue skeins of ice.

“Did you practice what I told you to?” her mother would scowl when she came home.

“She played brilliantly,” Aunt Yoshino would say, not really lying. “Didn’t you, Fujiko?”

She was a lovely girl: she had inherited her mother’s left eyebrow, but not its haughtiness; its curve lent her otherwise thoughtful expression a mischievous sparkle. “Well, you can’t send her to a public school,” her grandparents said, loosening the strings on their purse. “The children would make her life miserable.” Fujiko looked obviously, and — in the deliriously nationalistic Japan of the late 1930s — painfully foreign. At Aoyama Gakuin, an elite private school, Fujiko, mired in poverty (her grandparents would only do so much) tried to fit in with her wealthy classmates.

“Let me take a look at you,” Toako said, pushing the hair from Fujiko’s forehead. Fujiko was nine. They stood in the wings, waiting for Fujiko’s cue. Under the harsh lights, the slick black piano gleamed like a serpent. A friend of Toako’s was a violinist in the NHK orchestra. She’d told Toako that she’d see what she could do, so here they were. Fujiko was petrified. A technician, headphones bulging over his ears, pointed. Fujiko sat down and looked at the leering keys in front of her. She bent over the keyboard, closed her eyes, and smoothly drained the piano of Chopin’s Impromptus . “A genius!” “A prodigy!” critics trumpeted. Fujiko blinked in the glow of admiration. She was confused: her playing was worthless, she knew that; hadn’t her mother always told her so?

Toako realized she couldn’t keep pace with her daughter’s gift. Armed with Fujiko’s laurels, Toako again stormed Kreutzer’s ramparts; under his wing, Fujiko’s debut wouldn’t be far off. “I don’t teach children,” Kreutzer had grumbled into his cigar when Toako had implored before. Insistent, Toako played on Kreutzer’s former friendship with her absent husband. Kreutzer relented.

Fujiko didn’t. When she divined her mother’s plan, the terror that had seized her at the radio station hollowed out her stomach. Fujiko locked her knees, and Toako had to haul her all the way to Kreutzer’s house. The piano squatted in the parlor, broad slashes of light from the windows shining on its lid. Kreutzer, his bald head draped in blue cigar smoke, sat on the stool. His fingers disappeared as he pegged a pattern of arpeggios into the keys. “Now you try,” he said, smiling. Fujiko sat down. A white lily her father had painted hung framed on the wall. The stool was warm. She closed her eyes and rifled off a couple of Bach’s preludes, tightly stitching the counterpoint into a diaphanous weave, and before the hammers cooled after the last note of Chopin’s Minute Waltz ricocheted off the ceiling, Kreutzer exploded from his seat. “She’s amazing!” he cried, wrestling with his cigar. “A genius! She’ll astound audiences throughout the world!” Toako, beaming, asked about the fee. “Money? I wouldn’t think of it. I’ll teach her for free.”

Fujiko loved going to the house. The maid served tea and cakes. Kreutzer shook Fujiko’s hand before the lessons began. When her finger glanced off a key, Kreutzer gently guided it back. “Try it this way,” he’d say, smiling behind the blue cloud. He was never without his cigars, as if he couldn’t breathe without them, but when he played, eyes closed, the stogie lolling from side to side in his mouth, Fujiko saw in his face a deep rapture that she, too, felt — when her mother wasn’t around.

The headlines got bigger everyday. Most of America’s Pacific Fleet lay on the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Malaya, Borneo, and the Philippines fell in lightning strikes. But six months to the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the American navy scattered the Imperial fleet at Midway and Japan had effectively lost the war. By 1944, the home islands were under attack. B-29 bombers lumbered across the night sky, raining bombs on the cities. The fires died down and the smoke cleared, but the streets were crammed with cinder husks — arms and legs stretched pathetically toward the sky — and the stench of burned flesh lingered for days.

Toako, desperate to get the family out of Tokyo, took the children to live with Aunt Yoshino in Mitaka, a small town outside the city. An agent from the Kempeitai , the secret police, hammered on the door days later. “You have to go back,” he said. There was a military installation nearby, and she couldn’t be trusted. What was he talking about? “You’re married to a foreigner, right?” he said. “Your children aren’t Japanese, they’re Swedish.”

Back in Tokyo, Toako took the children to the Shibuya district office. The government was evacuating citizens to the countryside. She’d scrounged the money for train tickets to the southern prefecture of Okayama, but they couldn’t board without permission. “Forget it,” the clerk said, fanning his hand, his eyes already on the family behind them. Day after day Toako and the children fought to keep their place in line until finally the clerk stamped their authorization forms and the family scrambled onto the train. A month later, 334 B-29s raked Tokyo with 1,700 tons of bombs, roasting alive 100,000 people.

Toako brought her children home in August. Shibuya was a scorched plain of ash. Aunt Yoshino in Mitaka welcomed them into her family’s home. Food, scarce during the war, had nearly disappeared. Barley and potatoes were the main staple; protein was found in insects and vermin. People began starving to death; in Tokyo, more than a thousand died from malnutrition in the three months after the war. In October, the Americans began distributing food, but it wasn’t enough. The people scraped through the winter on rice gruel and a variety of wheat bran that was ordinarily cattle feed.

In 1944 the Kempeitai had stripped Kreutzer of his position and put him under house arrest. After Germany surrendered in May 1945, the Kempeitai had beaten him. At war’s end, the Tokyo National University of the Fine Arts and Music restored his professorship. The maid was gone, and there were no more tea or cakes. But Kreutzer still smiled, and somehow he had found a supplier of his beloved cigars. He and Fujiko began sketching out her debut.

The winters were harsh. People caught colds that lasted until spring. Fujiko, joints stiff, woke one morning with a fever. Sneezes racked her body, but instead of loosening the congestion behind her nose, they wrung out what little strength the fever hadn’t made off with. Doctors were few and far between; antibiotics, a black market luxury. Fujiko burrowed under her blankets, soaking her bed in sweat, hoping to grind the fever down. But the heat seared her for days, and when it finally abandoned her, it took a hostage — she was deaf in the right ear.

She thought she would suffocate in grief. She played, but the music no longer swelled with the full, round richness it had before. For weeks, Fujiko squared off against the piano; funneling her senses into her fingers, probing the keys for the sound that the fever had abducted. She didn’t stop until she wrested the music back, its nuances even more lush than they had been before. She was ready.

She debuted when she was seventeen. Kreutzer arranged the program: Chopin and Rachmaninoff. Fujiko stood in the wings, battling the anxiety clawing her stomach. The audience murmured in the darkness. Crouched on the stage, the gleaming piano waited. She strode across the floor, bowed, and before the last of the applause died down, began to play.

Toako put Step Three into operation: getting Fujiko into the Tokyo National University of the Fine Arts and Music. In 1950, college was an indulgence available only to the wealthiest. Fujiko shook her head in wonder; despite her victory over partial deafness and the successful debut, her mother had yet to dilute her acid tongue: “What you’re playing, that’s not music,” Toako would say; “A fool, that’s what I have for a daughter,” she would fume — and yet her mother had scrimped and saved to get her into music school!

Fujiko excelled. She was a runner-up in a national competition jointly sponsored by NHK and the Mainichi newspaper, and walked off the stage with the Culture Broadcasting Association’s first prize. But her relationship with Kreutzer suffered. With her own music flowing strongly in her heart, Fujiko resisted Kreutzer’s attempts to pull her into unfamiliar waters. When Kreutzer cancelled lessons to celebrate his marriage to a pupil, Fujiko made the break.

A year later, Fujiko was bent over the piano at home, working the kinks out of a Ravel sonata. Kreutzer, at a solo recital held at Aoyama Gakuin, had just sat down to bring Beethoven back to life. He was sixty-nine. After the war, the occupation authorities had forbidden him from playing in public for two years. When they let him back on stage, Kreutzer, to make up for lost time, held two hundred recitals throughout the country in a single year. Maybe he hadn’t recovered from the fatigue. His fingers slid off the keyboard and he collapsed. Behind Fujiko, a cabinet door flew open and banged shut. Her fingers froze over the keys.

At his funeral, Fujiko cried as she never had before. Her mother had taught her the piano, but Kreutzer had blessed her with music.

When Fujiko turned eighteen, the Swedish Embassy called and told her that since she had not established residence in Sweden her citizenship had been revoked. Fujiko went to City Hall. Her mother was Japanese, she explained, surely she was entitled to a Japanese passport. That’s not how it works, the clerk told her. Fujiko had been born on foreign soil to a Swedish father. She was stateless.

Fujiko pushed the problem from her mind; after graduating from college, she had been busy getting her name known: her solo recitals had attracted a following (whose resilient loyalty Fujiko would appreciate forty years later) and Watanabe Akeo, the distinguished conductor of the Japan Philharmonic, had conducted her. When the famous Samson Francois swept through Japan on his world tour, he attended a recital and lavishly praised her interpretations of Chopin and Liszt. Fujiko was grateful; but Francois’s tribute highlighted her dilemma: Japan in the late fifties was a small stage; Fujiko dreamed of taking her music to Europe. But without a passport, her career would wilt before it could flower.

“You must let Europe hear your music,” a man said effusively. Fujiko was mingling with the guests after a recital. The man introduced himself: he was the German ambassador. “Your Liszt and Chopin,” he continued, “is suffused with a marvelous Eastern delicateness.” Fujiko’s heart turned over. She couldn’t let this chance get away; she explained her problem. “Let me see what I can do,” the ambassador said.

What the ambassador could do was arrange for Fujiko to receive refugee status from the Red Cross and issue her a provisional German passport. Elated, Fujiko applied for and received a scholarship to the Berlin University of the Arts. Toako climbed onto the bus after her and, blubbering about how much she was going to miss her, pummeled Fujiko with insults all the way to Haneda Airport. The flight seemed endless, but finally, on a night packed with stars, the turboprop leaned over Tempelhof International. Berlin, glittering mounds of amber, sparkled beneath her.

Fujiko’s poverty followed her off the plane. All she owned were her clothes and a small silver bell. To stretch the hundred dollars her mother sent with a letter every month (“Here I am licking salt while you fritter my money away,” Toako would write), Fujiko rented a series of one room unheated flats, lived on potatoes, and when the last dollar was gone sipped sugar water until the postman showed up. She had lost her German, and when she found it again she couldn’t rub off the Japanese inflections: combined with her Asian features, the accent made some Germans despise her for what they interpreted as effrontery. At the university, Japanese students sneered at her shabby clothes, offended that she should be confused for one of them. Fujiko’s piano professor, dictatorial and aloof, made Fujiko long for Kreutzer’s warmth.

The only light in her life was the Berlin Philharmonic and its conductor, Herbert Von Karajan. When the orchestra performed at the university, students, admitted free, clambered for the best seats. They sat at the rear, behind the musicians, opposite Karajan and the hundreds of dim faces bobbing in the audience. The night Karajan conducted Beethoven’s Sixth, Fujiko sat closest to the stage directly across from the maestro . She watched, mesmerized, as Karajan, bathed in blue light, his steel gray hair swept back and his eyes closed tranquilly, conducted with such fluid grace that it seemed as if the musicians, having tuned their hearts to beat with his, would — should he suddenly stay his baton — tumble to the floor.

Karajan glanced at her. Fujiko couldn’t believe it. There, he did it again; the great Karajan was actually looking at her! Fujiko’s face burned and she averted her eyes. When the last strains faded and the audience roared its approval, Fujiko, face down, groped for the exit. Karajan wove through the orchestra and stood just below her. When their eyes met, he smiled. She hurried out.

The next day, Fujiko, battling cramps (the accompanist to a constant diet of potatoes), slipped into the concert hall. She had a plan. Karajan was putting the Phil through its paces. “Would you take this to the maestro please?” During a break she slipped the envelope to a violinist. She sat down, the relief of having gotten this far untying the knots in her stomach. Karajan wouldn’t deign to see her today, she knew that, and it was just as well: distracted by a failed love affair, she hadn’t been practicing. Karajan’s refusal to give an audience was legendary — remember the diva at the Metropolitan who, having beseeched His Eminence to conduct her, was kept on tenterhooks for four years only to have him refuse? Maybe someday, though, Karajan would condescend to hear Fujiko play, and with his support. . . .

The violinist trudged up the aisle. “The maestro will see you now.”

“What?”

This couldn’t be. Fujiko hadn’t meant today . Why, with a single word, Karajan could launch a career; if he were not amused, however, he could scuttle a performer’s dream in an instant.

“Fräulein, the maestro is waiting.”

The turtleneck sweater Karajan wore matched the color of his ice blue eyes. He repined on a sofa, her letter unfolded in his hand. A piano hunkered behind him.

“And what will you play for us, Fräulein Hemming?”

Panic tore her in half; she wasn’t ready. “Maestro, I am in no condition to perform.”

Karajan’s forehead furrowed. “You ask for an audience, and then you refuse to play?” Frost rimed his words.

Fujiko knew she’d founder if she set her fingers to the keys. “I cannot.” She stared at the floor. It was better not to perform, better to take her chances by just angering him, than to play and fail.

“If you would like to discuss this further, I am at the Savoy.”

Fujiko looked up. Karajan’s voice had thawed and his forehead was smooth. She took the paper from between his fingers, bowed, and scurried from the theater.

The next afternoon she got off the elevator at Karajan’s floor. She checked the paper for the suite number. The door was ajar. In the drawing room, a fresh pack of Marlboros and a datebook rested on a small table. The door to the bedroom was open. Fujiko peeked in. The maestro’s breaths were deep and even. Fujiko tip-toed into the corridor. The maestro was taking a nap. She never went back.

Fujiko graduated with honors and moved to Vienna to study under the pianist Paul Badura-Skoda. Accolades followed her sold-out recitals. Badura-Skoda’s praise was echoed by the pianists Shura Cherkassky and Nikita Magaloff. The Italian composer and conductor, Bruno Maderna (who lauded Fujiko so highly when he introduced her to the conductor Luigi Nono that Fujiko blushed), signed her on as a soloist. The German press hailed her as “the pianist from Japan born to play Chopin and Liszt;” the ARD introduced her in a nationwide program, and many of her recitals were broadcast on the radio.

But Maderna only came to Vienna twice a year, and while praise from fellow artists and the TV program were welcome, Fujiko was still destitute. She needed an influential backer, someone like Karajan, at whose nod the doors of the giant konzerthalle would open and recording contracts would unfurl. Now past thirty-five, time was running out.

In Vienna, she lived in a one-room flat bare of furnishings except for a bed, coal stove, and nightstand, on which she put her silver bell. For an extra few schillings a month, her landlord provided food: fatty strips of stewed pork. She didn’t have the money to eat anything else; she had to save: Leonard Bernstein was in Vienna to conduct Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion and Fujiko needed a ticket — her future depended on it.

She had written Bernstein a letter asking for his help. Tickets were expensive, so she bought a standing room only pass and stood in the aisle during the three-hour performance. Basking in the music, Fujiko forgot her roiling intestines and simmering fever. After Bernstein took his last bow, Fujiko, legs numb, hobbled backstage. She waited until the last of the well-wishers blew their good-bye kisses before she edged into the dressing room.

Bernstein, a cigarette in one hand, empty champagne glass in another, smiled at her. The room was warm, fragrant with the scent of his admirers’ bouquets. A piano beamed behind him.

“Maestro, have you read my letter?”

“Yes, I have,” he said gently.

Fujiko’s fear dissolved. Tears of relief tumbled down her cheeks.

“Won’t you play something for me?”

The anxiety flared up, but Fujiko was ready for it: “But, Maestro,” she muttered, “I’ve been standing for hours. I’m exhausted. I can’t possibly —” What was she doing? Excuses like these had made Karajan cut her adrift. She looked at Bernstein helplessly.

“Please,” he said, motioning to the piano.

Fujiko sat down and rested her fingers on the keys. She started with the classic canon — a prelude trickled along the banks of a meadow stream; flying buttresses rose to support the fugue that followed; a mazurka pirouetted into a corner — and then Fujiko nudged the piano into the upper west side of Manhattan: the Jets and the Sharks rumbled; Tony met a girl named Maria; a knife blade flashed; blood pooled on a ghetto basketball court. Exhausted, Fujiko slumped onto the keyboard. Bernstein put his hands on her shoulders. She stood up.

He kissed her on the cheek. “Leave it all to me,” he said.

It had been a severe winter: snow and ice that had fallen months ago still clung to the streets. After a day at the piano, Fujiko would slog home to a bowl of congealed pork in her tiny flat. The window leaked frigid air and the stove squatted cold in the corner; she couldn’t afford the coal to feed it.

The virus knocked her down a week before the performance. She dragged herself to bed and curled under her quilts, hoping to sweat it out. The fever blazed, and with each passing day she fell deeper into delirium. She saw herself in her dreams — calling, calling, trying to get her to wake. Her eyes fluttered open and she sat up. Her breath had fogged the window and frozen. What day was it? The sun was shining. She pushed open the window. The ice that had bound it shut slipped from the panes soundlessly. People walked below, mutely clapping their gloved hands together to keep them warm. She fell back onto the bed. Her bell spun off the nightstand and tumbled silently to the floor. Had it broken? She picked it up. The clapper was intact. She shook the bell, harder and harder, until her arm ached. But it answered her in a silence so deep that she couldn’t even hear her pulse pounding in her ears. She was totally deaf.

Somehow she stumbled through the first concert. She cancelled the rest. Life in Vienna became torture. She decided to flee. But where? To Sweden, to Stockholm, and to her father.

In the nearly thirty-five years that had passed since he had last seen his daughter, Fritz Gösta Georgii-Hemming had become a respected architect and the chief executive of the firm he had founded. Fujiko found his house and knocked on the door. A woman, an aunt whom Fujiko had never met, answered. Fritz was out of town with the family. Could she help? Fujiko explained who she was. Her new aunt phoned her brother; apparently, however, some unexpected business had come up: Fritz couldn’t see Fujiko — he’d get in touch as soon as he could.

But he didn’t. Fujiko’s aunt took her to City Hall and, after haggling with immigration officials, made sure Fujiko got back what was hers: at forty, Fujiko regained her Swedish citizenship.

Fujiko lived in complete silence for two years. Forty percent of her hearing returned to her left ear; her right ear would remain forever deaf. One morning, she screwed up her courage and sat down to the piano. It was a cold; the leaves on the distant birches a gold swath skirting the deep blue Scandinavian sky. But the keys, shining in the sunlight, were warm beneath her fingers. She closed her eyes and started over, just as she had when she was sixteen.

“Why did you bother?” Toako snorted. “Japan is full of young, talented pianists. There’s no place for you here.”

Fujiko had decided to come home; she missed her mother. Toako lived in a large building she had bought in Shimokitazawa in Tokyo. She still taught piano; for extra income she rented the third floor to a theatrical troupe.

“You didn’t make it, did you?” Toako cackled. “And you know why? Let me tell you: because deep down, you’re flawed, that’s why.”

Fujiko went to NHK. Her performances had been broadcast in Germany, Sweden, and Austria, she explained. Would they please consider featuring her on a program? NHK said they’d contact her, but Fujiko never heard from them.

“How embarrassing,” Toako sniffed when Fujiko told her. “Who wants to listen to a has-been who never was?”

Toako’s rancor wore Fujiko down. Fujiko remembered that her mother had never debuted, that Toako had spent her life teaching others to accomplish something she hadn’t attained. But sympathy had its limits. When Fujiko came home late one night, Toako accused her of sleeping around. “You know what venereal disease is, right?” she sneered. Fujiko began to protest, but Toako cut her off: “I was right,” she glowered, “you’re rotten to the core.”

Fujiko returned to Stockholm days later.

Her career was over, Fujiko knew, but not her talent. She received a scholarship to study musicology and was awarded teaching certification upon graduation. She waited year after year for her father to phone, but he didn’t. One afternoon, she decided to call him. “I’d love you to see you again, Fujiko,” her father said — she remembered the first time he’d called her, when her mother had to tear the receiver from her hand — “but we’ve made plans to go skiing in Norway.” Fujiko hung up. She didn’t call back.

Fujiko returned to Germany. She taught when she could. When times were hard, she scrubbed floors and washed bedpans in an assisted living center. Berlin, Hamburg, Heidelberg — she moved frequently, following lovers who never remained in the same place for long and who, eventually, strayed farther and farther away. She didn’t marry. As she grew older, she thought about getting steady work — she’d need a pension when she retired — so she taught at a music school in a quiet suburb for fifteen years. The small recitals she held attracted a handful of music lovers: businesspeople who traveled the world, attending concerts in New York, Tokyo, Berlin, and Rome. “What are you doing in this backwater?” they’d ask incredulously at the end of her performances. “You’re wasting your talent here.” She’d smile and agree; but all that was in the past.

She was bicycling her way home from a lesson. One minute the sun was high, throwing shadows from the tall elms sharp onto the road; the next, clouds muted the sky and the wind flattened leaves against the bicycle’s spokes. Fujiko’s brother, Wolf, had called a week earlier: their mother, ninety-one, was ill. Fujiko called the hospital; Toako’s voice was feeble. The sun stabbed through the clouds, and Fujiko blinked against the sudden heat bouncing off the asphalt. Dark feathers blurred a spot in front of her. A baby crow, wings crooked, was inching across the street. Fujiko gently placed it in her basket and began pedaling home. A black sheet flapped on her left. The mother crow, beak clapping furiously, was cutting the sky next to her. What should she do? If she got the baby home, perhaps she could nurse it back to health; if she left it to the mother, the bird would surely die. Fujiko threw the door shut behind her. She opened her hands and put the baby softly on the table. The phone rang. It was Wolf. Toako had just passed away. Fujiko hung up the phone. Several minutes passed before she remembered the baby crow. It was dead.

Fujiko brought everything back with her from Germany, even brooms and dust cloths. She wouldn’t starve — her pension could be mailed over, and she had renewed the theatrical troupe’s lease — but with the high price of living, she figured it was better to be safe than sorry. “Oh, you’ll be back,” Fujiko’s friends in Berlin had said. And maybe she would, if things didn’t work out in Tokyo.

She didn’t want to see her mother’s house fall into the hands of strangers. Maybe she was getting sentimental. It was 1996; thirty years had passed since she had gone to Europe. Tokyo had changed, and Fujiko spent two years getting used to the city. The house was so big it seemed a waste not to use it for something, so she began holding home recitals for close friends.

Pretty soon the house was too small for the number of people who came to hear her play. Her friends pulled strings, and before Fujiko knew what was happening, she was standing in the wings of her alma mater, the Tokyo National University of the Fine Arts and Music. Her signature piece was Liszt’s La Campanella. She could rattle it off the keyboard with the best of them if she wanted to; but she played it with a deep reverence that, especially toward the end of the piece — when the bells toll wave after wave — moved her audiences, who knew nothing about her, to tears.

Toyota Keiko, a television documentary writer, knew a good story when she smelled one. After the last encore, Keiko pushed her way to the stage. The woman seemed to be in her sixties — Keiko couldn’t tell; Miss Hemming’s left eyebrow, arched somewhat higher than the other, gave her a youthful, mischievous look. Keiko asked if she might ask a few questions, and the woman nodded.

NHK aired the documentary, Fujiko: The Miracle of a Pianist in the spring of 1999. Fujiko watched it at home with three friends. The phone rang shortly after it was over. It was NHK: calls were flooding their switchboards, viewers demanded to see the program again. So NHK aired it — three times in three months. Viewers wanted more, so a sequel was made. This was also rebroadcast.

Three months later, Fujiko made her first recording, a CD entitled La Campanella. The CD garnered Japan’s fourteenth Golden Disc Award and was named the Classical Album of the Year. At last count, sales of the CD had topped 900,000 copies. On January 17, 2000, the fifth anniversary of the Kobe earthquake, Fujiko performed in the city and donated the receipts to Kobe’s disaster relief fund. Concerts throughout the world followed. In June 2001, she played before a sold-out house in a small theater on the corner of 57th Street and Seventh Avenue in Manhattan. People call it Carnegie Hall.

This article was adapted from Miss Hemming’s books, Fujiko Hemming: Tamashi no Pianisuto (Fujiko Hemming: The Soul of a Pianist, published by Kyuryudo in 2000) and Fujiko Hemming: Unmei no Chikara (Fujiko Hemming: The Power of Fate, published by TBS Britannica in 2001). I am deeply grateful to Miss Hemming for her permission to publish her story.

DAVID GREER lives in Kochi City, Japan. In past issues of Kyoto Journal, he has profiled Sei Shonagon (KJ45), Yoshiyuki Aguri (KJ48), Dr. Takenaga Ken (KJ52) and Torihama Tomé (KJ53).