Interview with Francesca Lanzavecchia and Hunn Wai of Lanzavecchia + Wai

Multi-award-winning Italian and Singaporean duo Francesca Lanzavecchia and Hunn Wai are among the most promising young design talent working in East Asia today, tackling complex issues with their own unique brand of humour. They spoke to Lucinda Cowing online from Singapore, two days into Design Week 2016, on their latest collaboration, the challenges in taking advantage of new technologies, and the tools the next generation of designers need to navigate their ever-changing field.

Lucinda Cowing: I understand you are taking part in Singapore Design Week at the moment and that your new PLAYplay series being exhibited here came out of a collaboration with a local furniture restorer. Could you tell me about that?

Hunn Wai: Journey East is a 21 year-old furniture company that has always brought in vintage and reclaimed wood furniture, and two years ago they decided to address a market that they thought needed addressing: of first-time homeowners and young families. When these customers came enquiring about a solid wooden table they found it was out of their budget, which the owners thought was a waste of interest. We also felt that in this part of Asia there is an oversupply of Scandinavian furniture…

Francesca Lanzavecchia: Which, most of the time, doesn’t really answer the needs of the homeowners: size-wise, or material-wise. For instance, wool is so fine that in a tropical climate it doesn’t really make much sense.

HW: Maybe if you turn the AC on I guess!

FL: So we worked with them [Journey East] to try to define the spirit of a collection that these homeowners could feel they truly own, and that really represents the essence of South-East Asia. To them it was a big step from being retailers to becoming producers for this collection. Though it was our project, we brought them in with us during the whole process. HW: It was also about respecting the heritage of Journey East. The owners are very free-spirited. Their showroom is like their living room, so to anyone who comes in they will offer a glass of wine, and talk. Even if you don’t buy anything, you absolutely fall in love with the place. So we worked really well in that sense; there was no boundary between client and designer, rather it was four friends just trying to make this happen.

FL: We travelled to Indonesia together to source for the producers. It was really a complete design process, a design journey.

LC: So in that respect, was this collaboration quite different from others that you had done in the past?

FL: Yes. In a way we feel you get so much more “flavour” when you are able to control the whole process, from sourcing the material all the way through to how the products are communicated. For us it was the first time we curated the whole collection: sales, website, photography and video. The project started about two years ago.

LC: I get the impression that humour is really the hallmark of your work, would you agree? It seems to come through in the Play collection, but even your Austerity series seems to be quite a humorous way of approaching a subject as serious as food shortages.

FL: We like to call it “lightness,” like Calvino mentioned in his discourse1; it is a way to bring some positive thinking into the world. We need that lightness also to approach themes that are maybe too heavy to be approached by designs alone, so we try to turn it the other way around and look at things from another perspective.

HW: I think lightness too is needed in the world we are heading into; we are moving towards more and more sophisticated problems. For design to have a bigger impact, you have to handle more macro-scale things, so a certain lightness has to be maintained. When we speak with collaborators, we tell them we are here to help them dream and manifest those dreams in a manageable, scaleable formats.

LC: Speaking of helping people dream, your projects encompass both ready-to-use projects and speculative projects, so how do you strike that balance and what do you find those projects have in common?

FL: Well what they do have in common is the way we research and reach things. Regardless of the final aim—whether for a gallery or mass production, and certainly we have to build it in different ways or give it a different shape—the thinking behind it is mostly the same. We come from both a conceptual design and industrial design background. We like to follow that fine line between them, but I think people will more and more need products with a strong story, with a strong meaning, and that they will fall in love with.

HW: And that they can consume too. You have to be able to consume, to possess an object. True, powerful design should be like a glass in your hand and you should be able to use it every day. For that, you do need business components, mass production considerations— there’s no escaping that. How I see it is that we have a cloud above our heads filled with things that we just pull down, so it could be things that we’ve researched like for the elderly or for childcare, this crossover between accessibility and furniture, accessibility and technology. We put together whatever combination or cocktail is needed for the context, and it’s always an application context.

FL: At the end of the day the language you communicate with that decides what the public we are addressing is. You can go deeper; usually you can read our work in many layers, but it really depends on who we are addressing.

HW: These days, if we talk about creating real value and real innovation, it’s even about defining the context itself: as in designing the problem and then designing for that problem. That’s the fun part of it. It’s not so straight-forward anymore; if we are just asking the same questions about the same issues, then we will be beating around the same bush when really the bush is somewhere over there.

LC: With regards to mass production, a number of your projects have been created using 3D-printing, and the possibilities of 3D-printing are a hot topic within design at the moment, particularly with its potential for opensource design and rapid prototyping. How do you see 3D-printing developing in the coming years and how do you see it benefiting your practice?

FL: The greatest benefit is being able to prototype something quickly that is very close to what it will be at the final stage. We expected a few years ago that we would have our own printer in the studio. For me, I’m a little afraid of the “anyone can be a designer” idea; that instead of being something that will help us to consume less, it will produce a lot of waste instead. I am more concerned that on the ecological level that everyone will start printing, for example, disposable glasses for their birthday party, or stuff for their kids. I am sure at the same time that there be further developments from an ecological point of view. I read an article about the concerns surrounding the fact that you would be keeping hazardous materials, plastics, in your home. So before becoming really mainstream it needs a lot of adjustment.

HW: Right now I guess we are in the novelty phase. It is a vastly more democratic way of seeing something that you build through to reality, but it needs specialists to fine-tune it for production. The technology came out the industrial design sector and was primarily for prototyping, but now when it comes to transitioning from that to a final product state, it is still difficult to move beyond trinkets.

FL: Also you cannot pretend that you can draw a lampshade, you print it out, and it’s done. You really need to consider how much heat is coming out, whether the product is going to become more yellow and so on: things that a designer knows. For sure I think the most interesting part is the possibility of bringing in a flexible system. For instance, our partly-glass lamp is printed much smaller than it really is, but only when you lift it up does it change shape. Being able to print something that lies in between a textile and a rigid shape is the stronger side of 3D printing.

HW: Many designers right now are trying to figure out what the new natural application for 3D printing could be. If you think about a material like wood for example, there is certain a way to cut it, treat it and respect it, but now you have this two-faced thing that we don’t know what to do with; and 3D printed objects have a certain sleekness that is somewhat disconcerting. There are many interesting experiments happening by many designers, such as printing in clay, and introducing error diffusion algorithms.

FL: I think we both talking about having the flexibility of a system here, instead of perfection of the final result.

LC: And of course you do make use of natural materials as well, so do you feel high levels of craftsmanship still have a place in modern design?

FL: We think it must do, given our culture and past. We like to think that both things can coexist, even in the same product. Our lamps for instance are mouth-blown glass from Venice and half 3D printed. Why not?

HW: Or to weave sensors into carpets or beautiful tapestries.. It’s more “why not?” rather than “stop stop, we need to draw some borders!”

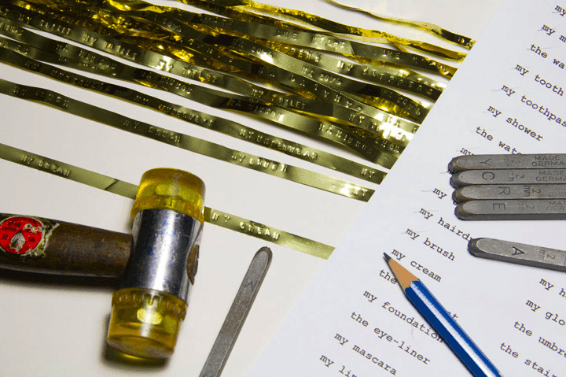

LC: One project that stood out for me was One Day in the Life of VM on Earth which looks at the idea of literally imprinting someone’s identity onto an object, recording all the mundane events of their life. I wonder what your philosophy is concerning personal identity and the objects we live with every day; how important a consideration is this as compared to other aspects of design like say, functionality?

FL: The idea behind the project was to create what would be the only object you could bring together with you on the “New Earth.” The project was called Another Terra, for a special exhibition in 2012. We asked ourselves, “Would we bring an object with us, or just the memory of that object?” What we initially thought was: of course, if I did bring an object I would bring something that is functional—I would need some heat and so forth—but what we really wanted was the memory of the most ordinary day of earth that would never be possible again on Kepler 21-B. The things that go unnoticed, that give us quality of life, everyday things like the sound of my alarm clock—which is different from yours. We were looking at how objects can mould our attitudes and behaviour, and also how things taken for granted can suddenly be taken away from you.

HW:I think we are most interested in the relationships we have with our objects and that objects have with space: like how many steps you take to go through the door. It is our job to figure this out as designers, so we always design from the standpoint of what behaviours we choose or what lifestyles we want to enable. That’s becoming the way to move forward, not “oh, let’s design a new table.”

FL: It is about the scale of intimacy we can establish with an object too. In the case of Another Day of Earth, it is a very intimate object; you can imagine it to be like a second skin of memories that you can envelop yourself with and brings you into a cloud of thoughts. It could have been a completely different scale. HW: It could have been architectural, like a tent or..

FL: Or just sounds in a room.

LC: And how about the influence of both your home cultures— of Italy and Singapore respectively — how do they manifest in your work? Do you feel that they do particularly?

FL: Our mums might have been getting angry at exactly the same things, but these were very different ways we grew up: from the colours to the climate. We like to think that we are not that influenced by our background but it is impossible.

HW: Italy is a place that has centuries of history, but Singapore is only 51 years old and we are constantly creating the future. I think it’s a nice contrast.

FL: We actually feed off each other. I come here to find the freshness and he comes to Italy for the history. We like to travel, and we get ‘fed’ by every country that we go to. We have projects in Indonesia, United States, Hong Kong and when we visit clients we try to live and perceive things as the locals do.

HW: It is a joy to learn about the motivations of different cultures and ask what comforts you, what makes you happy.

LC: A more generic question perhaps, but what was your calling to design? How did you end up what you’re doing?

HW: My first contact with design was a matchbox 1985 Audi rally car. I started fanatically drawing cars from Audi to Alpha Romeo every day, and was convinced I was going to be a car designer. Later, I wanted to be an artist but my parents said no, there’s no money in that, maybe architecture is acceptable. Then I got a prospectus for a university in Singapore with a new course in industrial design. I went to my uncle, a banker, to ask what he thought, and he told me to go for it. Architecture, on hindsight, would have been tortuous because of the length of projects, but in industrial design you get to touch many realms and work fast. I get bored pretty quickly, so I need to move quickly!

FL: As for me, I have been collecting things almost since I was born. As a child I was imagining in the year 2000 that the world would explode and on my floating, heartshaped balloons I would bring all my things with me. These days I care much less about owning things, but it all started with a love of objects. And I was one of those students who was always drawing things at the back of the class; I was better at visual things than with words. My parents pushed me towards medicine. I passed the test, but I ended up in design. I am really happy it happened this way because I would never have been able to continue to carry on with my ‘selfish side.’

LC: You both graduated from Eindhoven, the highly-regarded academy, didn’t you? What was your biggest takeaway from there was, and what do you think might be important in educating a new generation of designers?

FL: We were constantly to explain the “why” of everything, and I think that was very important. In Italian university the approach was, “OK do your thing, whether good or bad, it doesn’t really matter.” HW: You could be “chopped off” at any point. Adios! Ciao! It was immensely stressful, survivor- like conditions. You had to really know why you were doing design! Each of us came out stronger, but not without having our ideas completely destroyed.

FL: To really understand what matters to us as designers, we were able to work on topics we thought are relevant for a whole year, and with very harsh critique you really need to believe in it. After that everything is like fresh water! It was probably the first place that we were able to come into contact with so many different cultures, we were about 20 different nationalities and in such a difficult environment it means your family is from 20 different countries than yours! It was the worst and best time of our lives.

HW: I teach part-time at the Art Academy in Singapore. I think there has been a shift and we are trying to handle problems bigger than just a table and chair, or even issues like whether an object still makes sense in these shrinking urban flats. What we try to enforce in education is to be research and insights driven, to be informed by what the user needs and crystallize it into something valuable. It is also about transitioning as well. We need to train them to be thinkers and be sensitive to the world around them, because we cannot afford keep producing just more stuff. Of course we can choose to do so, to be ignorant, but given how informed we are it’s just not right. I don’t think I want to give the students the full “Dutch treatment” because I think they might crumble! At the end of the day it is about creating confidence. Students may open a café or go on to create the next world-changing app with the same skill set. I can show them my way of doing and viewing things, but objectively speaking they need to be able to find the tools for themselves. I can open them up to possibilities in design, but it is their own journey.

Lucinda Cowing is director at Kyoto Journal.

Thanks to Marlies Peeters who contributed research.

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013