[C]onsider the title. What does it mean to connect the fifty women artists of sixteen different Asian countries and regions represented in this exhibition by calling them “Women In-Between”? The title is one that makes us wonder, first, how one might describe an existence that is between boundaries. Is this an experience that is neither one nor the other? Or is it an experience of both? Do liminal entities peer in from the edges? Or do the artists look around, taking their standing ground as center?

These are only some possible responses, and a viewer will find at the exhibition diverse accounts of what it means to live each day between boundaries. Kokatsu Reiko, chief curator of Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, describes her vision behind the exhibition as follows: “’Women In-Between’ designates […] women who […] mediate in areas of confrontation [such] as races, borders, religions or genders, without anchoring fast in a certain fixed value or attitude, standing not in the centre but interstices […] because of the given condition of women as a minority.”

The accumulation of days lived between boundaries may not only enhance one’s ability to adapt, but also lead to an awareness of the arbitrariness of those constructed borders. Women in-between, then, possess a certain acumen as well as resilience. As a description, the title at once speaks to and of the voices from the margins, the acts of crossing and transcending boundaries, and the fight for what is ultimately human freedom as a perpetual work-in-progress.

Those who step gingerly around feminisms may be wary in their approach this exhibition. Still, one quickly comes to understand this as another powerful assertion of humanity. In this more universal sense, to be in the presence of these works is to actually feel the ongoing processes of reaching and of navigating—a human experience. It is to be made to feel and think about other realities, our own realities, what we take for granted and what still calls for attention and redress.

This is a glimpse of a few of the works.

Born in Aligarh, India, 1937 | Lives and works in New York, USA

Once I lived in a house of many rooms

I walk from room to room

Touching the walls

Boundaries of despair

[T]his set of four prints is, at a glance, static and minimalistic. Some time spent with them, however, reveals them to be almost trembling with energy, lines an organic foamy charcoal. The story begins with a grid of isolated rooms which progressively open up and connect and overlap, ending in darkness. In her catalog commentary, Kuroda Raiji offers an interpretation in which these texts and visuals—especially if considered alongside the artist’s past experiences of constant migration and displacement—can be seen as working through a process of personal isolation, desires for other-oriented encounters, the anxiety throughout, and finally a certain stillness and totality. Whether this final state is one of despair or repose, or something else altogether, is dependent upon the lens through which the viewer sees the world.

Zarina’s work retains a formal quality reminiscent of Minimalism that is in contrast with common works by Indian artists and has prompted criticism for being too “Westernized.” Raiji clarifies, however, that the artist was inspired less by the American influence of the time and more by forms based on Islamic Sufism which seeks the purification of the spirit through freedom from the worldly. In these pieces in particular, the simplicity is profound and effective in conveying human solitude.

Born in Bangkok, Thailand, 1961 | Lives and works in Bangkok, Thailand

[A]fter personally experiencing pregnancy and childbirth, Pinaree has come to focus on the shape and functions of the female body, as well as the roles of women. She focuses here specifically on breasts as symbols and vessels of vitality, the shapes of which overlap with the shapes of stupa in Thailand. According to Rawanchaikul Toshiko in her catalog commentary, such appropriately embodies what the artist pursues—the experience of woman, identity as a Thai artist, and sanctity.

Breast Stupas is her first large-scale work. Large sheets of hand-woven Thai silk on which appear carefully stitched shapes of breast/stupa are hung from the ceiling, creating a smoky-hued forest meant to be walked through, meant to create an experience that articulates the beauty, sanctity and strength of woman. Her other series, and everything in between, also evokes the image of breast and stupa, though more subtly. The artist says of the series, “It’s about reading between the lines, about presence and absence, about subtlety, about life.”

Her works and expressions of breasts and stupa vary from painting to installation to textiles and, in recent years, even to cookery.

Born in Chia-yi, Taiwan, 1962 | Lives and Works in Kaoshiung, Taiwan

[S]hur-Tsy began her series of photographic interviews after visiting villages and towns in Taiwan overflowing with Vietnamese food stands, heavily-accented girls doing agricultural work, and advertisements for “Vietnamese Brides.”

According to Hara Maiko, in her catalog commentary, “… in recent years, roughly 95% of those naturalized in Taiwan are foreign brides. They include women from Vietnam, Indonesia, and other Southeast Asian countries. Most of these women come from poor areas through an introduction to a Taiwanese man from a matchmaking service. Waiting for them in Taiwan are language barriers, differences in lifestyle and customs, misunderstandings that lead to abuse, and problems educating their children, among other difficulties.” In this specific series, large photographs of the foreign brides and their families are paired with their stories and “confessions.”

Born in Faisalabad, Pakistan, 1972 | Lives and works in Lahore, Pakistan

[I]n the Western imagination, the veil has long been a symbol of women’s oppression in Islamic parts of the world. Pakistani artist Aisha Khalid unflinchingly addresses and adds nuance to this conception in her work, depicting figures wearing the burqa in front of intricate, geometric patterns. As pointed out by Igarashi Rina in her commentary, these backgrounds resemble the patterns of chadi wari, the cloth that covers the walls of women-only living spaces. In Silence with Pattern, a number of figures in uniform black burqas float in rows in front of a colorful patterned background. Their shapes as recognizable human forms as well as their stark black color and single crimson rose adorning each figure draw the viewer’s gaze to them, but the figures have no eyes with which they return our gaze. In fact, they seem as though they are part of the pattern: the women are placed in equal distances from each other, and some of their bodies are truncated at the painting’s edges. These women are on one hand invisible, because they are obscured by their burqas and they become part of the background in themselves. On the other hand, they are striking elements of the painting which the viewer cannot disregard. Their motionlessness, then, may be a stillness, but not necessarily immobility; their silence does not imply their being silenced.

Khalid’s works in this exhibition reflect her training in miniature painting, which is an art form that was solely practiced by men, primarily from the 16th to 19th century (Igarashi Rina). This genre continues to be appropriated and revitalized by a number of contemporary women artists who use it to explore present-day issues such as politics, militarism, and gender issues.

Born in Okinawa, Japan, 1953 | Lives and works in Okinawa

[I]shikawa Mao is a photographer whose work is strongly rooted in her life in Okinawa. This means that as much as Okinawa is a place of fluctuations and diversity, her works are of many different subjects and topics; they are also often imbued with a sense of movement.

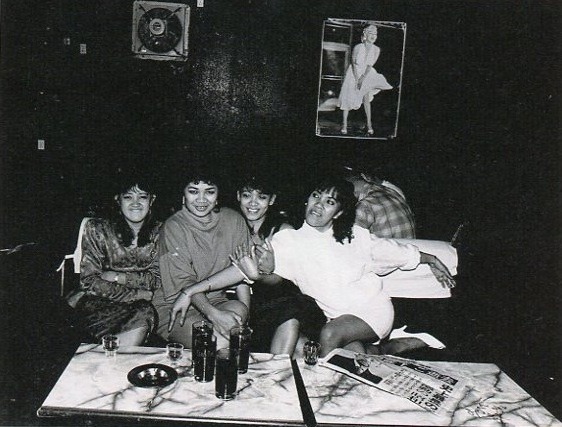

Her black-and-white photo series Philippine Dancers found its spark when she visited, in 1986, a bar for black soldiers in Kin, Okinawa (Tomiyama Megumi). Having worked at this bar in 1976, she was surprised to find that there were many more Filipina workers there than there had been a decade before (Ibid.). She then made her way to Manila, Philippines, where the workers’ families lived, as well as Olongapo, Philippines, another US army base location. Her photographs of the women and their lives in these three locations allow us glimpses of intimate settings and spontaneous expressions. In these photographs that clearly reflect her personal ties to her subjects, Mao reminds the viewer that the migrations of people may be motivated and constructed by economic forces but can never be reduced to mere transactions of money and service. As Tomiyama Megumi writes in her catalog commentary, these constitute homage to “those women who live every moment with all their might.”

This exhibit was jointly planned and implemented by the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, the Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum, the Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, and the Mie Prefectural Art Museum.

Hien Luu, from Notre Dame University, Indiana, and Jodie Moon, from Reed College, Oregon, were summer interns at Kyoto Journal.