[I]t’s 7am I’m not supposed to wake up till at least 9:30, but as long as I keep the curtains closed, I’ll be okay. Outside my apartment, the people with ‘real’ jobs are already on their way to work. Before my ‘official awakening’ I secretly spend my time studying kanji. This has to be kept between ourselves. If it ever got out that I was doing this I could well lose my job.

For breakfast, it’s my favorite, natto, on rice, a delicious, healthy concoction, but it always means I have to brush my teeth twice and rinse with mouthwash to eradicate the tell-tale natto breath that I’m not supposed to have. I also have to avoid putting the discarded natto tubs in the garbage as this would be a sure giveaway. Instead I put out empty waffles packets.

Around 10am, the doorbell rings. I quickly stash the kanji books under the mattress and switch on the cable TV, being sure to turn to MTV. Just as I’m about to open the door, I realize with a shudder that I’m not wearing any shoes. I quickly struggle into my brown loafers and open the door with my pajamas on. I must look rather stupid, but I don’t care. The main thing is to avoid a serious faux pas like going shoe-less indoors. It only turns out to be the postman, but you can never be too careful in my line of work.

After thanking him with a few mispronounced ‘text-book-wrong’ Japanese phrases, I take delivery of a bubble-packed envelope. It’s the latest big budget Hollywood movie on DVD, a whole 6 months before its release in Japan. I throw it unwatched onto a pile of similar junk that I’ve accumulated in the last few months, and I also switch the TV over to an NHK program about onsen in Gunma Prefecture.

At 11:30, I dress and go out. Today, in accordance with my coded e-mail instructions, I’m sporting a backwards-pointing baseball cap, stick-on goatee, and wraparound shades. I guess I’m supposed to be a ‘cool’ slacker gaijin today.

Walking down the street chewing gum, I warm up, swiveling my shoulders, trying to take up more space than I need. I also start craning my neck and looking at everything with an affected sense of naive wonder. This might sound quite difficult, but with a lot of practice in front of the mirror every night, I find it possible to be convincing enough to fool any casual observer.

I take the subway into Shinjuku, taking care to buy the wrong ticket, and blunder through the ticket gate without paying the full fare. When I arrive, it is already lunchtime. I wander round the area sometimes known as “P*ss Alley,” a little block of smoky, cramped, ramshackle low-rise bars and restaurants, surrounded by modern high-rise buildings in the heart of the city.

I take especial care to gawk at a cramped kaiten-zushi restaurant. I’ve seen a million of these babies, with their little dishes of rotating sushi, but I give it all I’m worth for a full 15 minutes, gawping, pressing my face up against the glass, shaking my head in disbelief, walking away and coming back to have another look. The shop owner finally invites me in, but I give him a look of horror, say “Oh my God” in an exaggerated voice, and – having put in an excellent though hammy performance – I beat a hasty retreat.

Instead I drop into a nearby ramen shop for lunch, but this is a working lunch, as I have to point to the pictures even though I know the Japanese name for everything on the menu. Then I have to fumble with my chopsticks for several minutes, even sticking them up my nose, until the waitress feels enough pity to bring me a fork and a spoon.

At 1:30 I stop a random stranger on the street, and ask how to get to Akihabara. It may surprise you, but this is one of my special duties. I’m supposed to do one of these every three hours. The old lady I pick on doesn’t understand a word of English. I almost feel like making it easier for her by using just a smidgen of Japanese, but the Company is very strict about this. The ‘Standard Operating Procedure’ in a case like this is to repeat the question several times, each time slower and louder, much louder.

Soon a group of Japanese people gather round. My big fear in a situation like this is that someone will actually volunteer to guide me personally to Akihabara, so that I’ll actually have to go there, but thankfully such cases are extremely rare nowadays. Instead, the little cluster I’ve attracted put their heads together and draw me a railway map and a sign in Japanese which says, “Excuse me, please direct this honored visitor to the Akihabara train.”

Two of them, a middle-aged man and a high school girl, using broken English, then volunteer to lead me to Shinjuku Station and help me buy a ticket. They bow and wave goodbye to me as I pass uncertainly through the ticket barrier. I immediately head towards the wrong platform as they frantically try to wave me in the right direction. Finally I pretend to understand and head for the Sobu Line platform.

After I’m sure the coast is clear I backtrack and get the Yamanote Line down to Shibuya. The station is busy and crowded, but years of living in Japan have given me an almost bat-like sense, enabling me to avoid bumping into people without even trying. However, this is strictly against Company policy, so I immediately start bumping into people. I’m way under quota, I realize, so I have to work extra hard at this for the next ten minutes or so, just wandering around the station bumping into people and apologizing.

Eventually I get on the train and arrive in Shibuya, the ‘Grand Central’ of the Tokyo youth scene. As we’re employed to especially make an impression on malleable young minds, this is the ideal working location. I make my way to the famous Hachiko statue and wander around looking at my watch, as if I’ve been stood up by a girl. This takes me to 3 o’clock, after which I do a bit more acting lost, pulling out my map in front of the 109 Building. No one helps me.

I then wander halfway up Dogenzaka, trying to look lost. Small, purposeful Japanese people swirl around me, feeling a tad smug at my discomfort. They’ve all got places to go, things to do, people to meet, whereas I’ve apparently wandered off the tourist trail. But their self satisfaction doesn’t bother me in the least. They’re not the ones getting paid one and a half a million yen a month for doing almost nothing.

[I] THEN HEAD to one of the popular backstreets. Among my more enjoyable duties is staring at the high school girls with their latest freaky fashion. They’ve now grown out of dark suntans, dayglo lipstick and leg-breaking platform soles, and are into wearing little cats’ ears or rabbit’s ears on their heads – anything to be cute! I make their day by asking some girls if I can take a picture to show my folks back in Kansas. They don’t know Kansas, so I quickly say California instead. Luckily they’ve heard of it.

I now decide to perform another vital function of my job, showing sexual interest. I start hitting up on various women, using only English and a lot of crude body language. Some are shocked and stone cold me, others giggle appreciatively, while a few even touchingly offer me directions to Akihabara. The rules of the professional gaijin with regard to fraternization are very explicit. We are only allowed to conduct our relationships in English and must go out of our way to show a gross insensitivity towards Japanese culture. My specialty is to invite them for a meal and then stand my chopsticks up in my rice. As this is the way rice is offered to the dead at funerals, it’s extremely taboo and never fails to get the desired effect.

Most of us deal with the limitations on relationships by trawling the dreg holes of Roppongi. Here we can speak English and show great insensitivity to Japanese culture and still be very popular. It may be very difficult to see, but my purposefully flailing attempts to nanpa or chat up a few high school girls, provides immense secret glee and satisfaction to adjacent Japanese males.

After fulfilling my duties in this respect, my next stop is Tower Records, where I studiously ignore the latest Japanese releases, and go straight to the imported music section where I listen on the headphones and sing along. After mildly freaking out a few more innocent Japanese people, I head back out on the street and ask someone else the way to Akihabara, which I completely mispronounce on purpose as “Aki-harabara.” The young man I ask tries his best to understand me as I start raising my voice. Eventually, he panics and points me in the direction of the nearest McDonalds.

[I]T’S ALMOST 4:30, so I decide it’s time for a break. Of course, I’d much rather have a delicious, healthy, and invigorating cup of Japanese o-cha, but that’s definitely out of bounds in public. So, instead, I head to McDonalds and buy a disgustingly sweet milkshake. As I sit noisily sucking through the straw, I take out a voluminous tome on the history of Western philosophy. Little do the people around me realize that I have carefully secreted pages from my favorite Japanese manga between the pages. The main thing is that Japanese people must see me reading a book that evokes both their awe and their pity, regardless of what I’m actually reading.

As I sit there pretending to read philosophy, I notice another gaijin and realize that I’ve seen him before. It’s Clark, one of my colleagues from the training sessions, a Brit with terrible teeth and a beaky nose. They’ve got him doing his eccentric ‘Brit’ act today as he’s wearing an Argyle sweater, has his hair in a louche cow-lick, and has a large Mod target sewn onto the side of his shoulder bag. Although it’s frowned upon for us to consort in public, I greet him and ask how things are going. He looks at me a little uneasily.

“Wot you doing here?” he asks defensively.

“On the job,” I reply. “Just asked someone the way to Akihab. Got directed here.”

Clark looks around, nervously, as if he’s being tailed by the secret police. Of course, from time to time, the Company does monitor our performance. So it’s never a good idea to fall behind with quotas or neglect our various duties. But, still, it’s such an easy and well paid job, what could possibly be wrong?

“Not a bad life, is it?” I say, trying to draw him out. “¥50,000 a day for doing next to nothing.”

“You mean for living a lie,” he sneers.

So, that’s it — a crisis of morale. I try to find out more.

“It’s more like show business,” I casually offer. “It’s all about bullshitting people to make them happier.”

He gives me a look like I’ve just swallowed a cockroach.

“Well, that’s not what I want to have carved on my tombstone,” he sneers.

[I] WAS WARNED about this. Usually, after a few months, most professional gaijin go through something we call ‘the dark night of the soul,’ when their conscience starts to bother them and they ask themselves whether this is what they really want to do with their life, etc. etc. At this point, the fact that they are being extremely well-paid actually makes it more likely that they will quit, because, while it gives them the means to stop working for several months or even years, it also makes them feel like they’ve sold their souls to the Devil.

“I know it’s a rather strange occupation,” I try to mellow him. “It’s definitely not one you grow up hoping to do, but the way they explained it to us at training made perfect sense.”

“Ha!” he laughs scornfully. “You mean all that crap about Japan being a culture that can’t cope with too many differences?”

“Well, that’s right,” I argue. “After all they’ve only had about 140 years to come to terms with the fact that foreigners exist on the same planet with them. After being struck with fear, hatred, and awe, they’ve finally managed to work out some cozy idea of us as big, harmless, lazy, lecherous, clumsy, natto-hating, shoe-wearing, cheese-munching, beer-swilling, book-reading klutzes…”

“…who have little understanding of the finer points of Japanese culture and civilization, and are only attractive to the lowest kind of Japanese woman,” he finishes my sentence. “I know. I’ve memorized the same training manual as you.”

“Yes, but, it’s true,” I insist. “As long as they can believe that, they’ll feel happy doing business with us and playing a part in the world. We mediate between their half-baked idea of us and the complex reality of foreigners. Without us, they would be lost. Gaijins would become completely alien, unpredictable, and threatening again. Who knows, they might even kick us all out and shut up shop again for another 250 years. All we’re doing is breaking their fall into the real world. A strange job but a vital one.”

“Pah,” he sneers. “It’s not hard to find explanations when you’re getting a million and a half a month. I don’t care about money anymore. I’ve got plenty of it. But as far as my integrity goes, it’s not worth this.” He snaps his fingers. “I can’t stand this anymore. I’m leaving. I’m getting a one-way ticket back to reality.”

“Wait, think about the wonderful opportunity you’re throwing away,” I implore one last time as he rises. Instinctively I grab his arm. As he whips it away, he accidentally brushes my face, knocking off my fake goatee.

As I fumble with it, trying to reattach it, he storms out. The same bat-sense that helps me to avoid bumping into people now tells me that a wall of unseen eyes has descended upon me. I decide to leave as well and lose myself in the crowd.

Clark is naive. You can’t rock the boat like that. The men from the Company have thought everything out. He’ll either leave for good or he’ll just be characterized as another nutcase, an oddball, along with any other jerk who thinks he can open the eyes of the Japanese and interact with them on the same level by teaching them his culture and trying to learn theirs. All they want or need is a cozy caricature of us, so why shouldn’t we provide it?

I know which side my bread is nattoed on. It’s a once in a lifetime opportunity being a professional gaijin, but you’ve got to have the right attitude. You’ve got to be mentally tough and have a healthy appetite for money.

Right, it’s time to go and get drunk without getting red in the face.

C.B. Liddell is a writer, editor, and occasional Viz cartoonist who teaches English to high school students as a hobby.

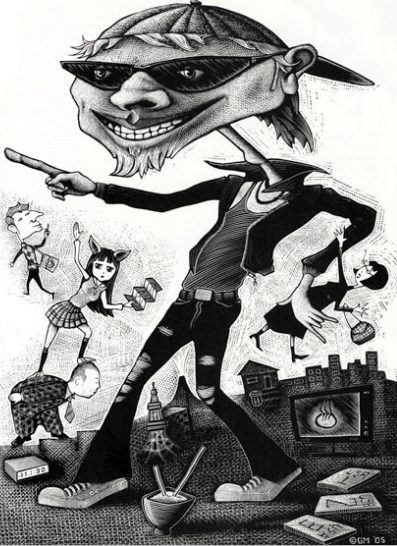

Artwork by Gregory Myers