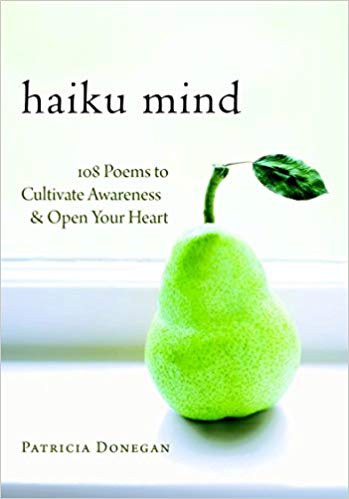

Haiku Mind, 108 Poems to Cultivate Awareness & Open Your Heart (Shambhala 2008)

[I] wanted to write this book to share the idea of “haiku mind” — a simple yet profound way of seeing our everyday world and living our lives with the awareness of the moment expressed in haiku — and to therefore hopefully inspire others to live with more clarity, compassion and peace. The root of haiku mind is found in the widely-known poetic form of haiku, a form of poetry that contains seventeen syllables in three phrases (5-7-5) in Japanese or usually three lines in English. A fine haiku presents a crystalline moment of heightened awareness in simple imagery, traditionally using a kigo or season word from nature. It is this crystalline moment that is most appealing. However, this moment is more than a reflection of our day-to-day life — it is a deep reminder for us to pause and be present to the details of the everyday. It is this way of being in the world with an awakened, open-hearted awareness — of being mindful of the ordinary moments of our lives — that I’ve come to call “haiku mind.”

This is not just an anthology of haiku poems, but rather spiritual reflections on 108 haiku. In Buddhist thought as there are 108 difficulties to overcome in order to become awakened, and so there are 108 beads on a Buddhist mala. The reflective form I used was inspired by the Japanese tradition of the haibun: hai (haiku) and bun (sentences) combined. This is usually the story or reflection behind the poem. These reflections are meditations rather than literary analysis. Each of the 108 haiku is a meditative springboard for the contemplation of a specific theme, be it adversity, nowness, or compassion. My reflections are often in a poetic-prose style, interwoven into a tapestry using the thematic threads of the poetic, the spiritual, and the political. Hopefully each haiku and each reflection will encourage further contemplation — and will cultivate a sense of awareness, compassion, and peace.“compassion instead of revenge”

to the one breaking it—

the fragrance

of the plum

CHIYO-NI

HER CLOTHES burned off, the naked Vietnamese girl is running, running down the road, running for her life; red-hot napalm firebombs trail after her. She is screaming, crying out in agony with arms outstretched, as if signaling, signaling to us for help… That was the unforgettable image of 1972, the Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of the nine-year-old girl that personalized the horror of the war for us in America and world-wide, and helped end it. Thirty years later, I hear a lecture by this now-grown woman, Kim Phuc, who not only amazingly survived that experience, but who has forgiven her attackers and is now circling the globe, working for UNESCO and her own foundation for war-torn children, telling her story as a “goodwill ambassador,” arms outstretched for peace. In this haiku’s depiction, although a hand breaks the branch of the flowering plum to enjoy its scent and beauty — the tree, like the Vietnamese woman, reaches out and gives back its deepest fragrance. This is what Christians call the act of “forgiving one’s enemies,” which is beyond any human logic or comprehension. Yet in the end, it may be the only thing that works, that will bring us lasting peace: to reach out to the others, to finally heal what has been broken, this cracking of a plum branch.

CHIYO-NI (1703-1775). One of the greatest traditional Japanese woman haiku poets. Born into a scroll-maker’s family, she studied with two of Basho’s disciples, was a renowned renga master, painter and Buddhist nun, She published two poetry books: Chiyo-ni Kushu (Chiyo-ni’s Haiku Collection) and Matsu no Koe (Voice of the Pine). See Chiyo-ni: Woman Haiku Master by Patricia Donegan and Yoshie Ishibashi.

disgusting—

people arguing over

the price of orchids

MASAOKA SHIKI

GREED, once one of the seven deadly sins of human beings, warned against in medieval Christian culture, has expanded through Western capitalism into the globalized culture of hyperconsumerism. Whether on an international or personal scale, it is difficult to switch our allegiance and notice the beauty of the pristine white orchids nodding in the hazy sunlight, and to realize the absurdity of wanting more and more. The poet here, even a hundred years ago in Japan, saw the same human axiom at work. Today this is a worldwide reality: when one or two percent of the world’s people own most of the wealth and when the acquisition system of multinational corporations flowers on a world scale, the result is not just orchids that are at stake, but the depletion of human and natural resources, resulting in plague, famine, war, and the ruin of the environment. Only when human beings realize that everything on earth is interdependent can we switch our thinking from competition to cooperation, from greed to compassion. Then we will be able to just admire the orchids, perhaps together.

MASAOKA SHIKI (1867-1902). One of the four greats along with Basho, Buson, and Issa, Shiki is considered the father of modern Japanese haiku. He created “haiku” by totally cutting hokku (starting verse) from the longer linked form of renga, and giving it a new name. He was also a tanka poet and haiku theorist, espousing Buson over Basho and a “sketch from life” style. He lived with tuberculosis and died young; his haiku group’s magazine was Hototogisu (Cuckoo). His works include a diary called A Drop of Ink and Haiku Notebook of the Otter’s Den; his disciples include the major poets Kyoshi and Hekigodo.

violets here and there

in the ruins

of my burnt house

CHOKYU-NI

THIS HAIKU has haunted me: the poet’s response to her personal tragedy and her original preface to this poem are inspirational, “On my return from Tsukushi at the close of March, I found that my hut had been destroyed by fire. Looking at the ruins, I composed this verse.” This haiku addresses the age-old question we all face: how to work with adversity in our own lives, and in this chaotic, imperfect world around us. We cannot ultimately control what happens, but we can control our response to what happens. This becomes the spiritual path for each of us, however we find it. We could cry and rage or deny what happens, which may be part of the process, and perhaps the process the poet went through herself before or after she wrote this haiku. Yet sometimes adversity can be an opportunity rather than an obstacle, if we are simply aware of our daily response to things, examining what happens with courage and openness, and possibly reflecting upon it as in this haiku. It is not being optimistic or looking for a silver lining, but just seeing the way things are: the burnt charcoal of the wooden house and the tiny flowers growing nearby — to see the paradox, the complexity, how the good and bad are often intertwined. This haiku reminds us how to work with personal tragedy, how to work with natural disasters, plague, famine and war — how to see violets in the ruins… or whatever happens to be there.

CHOKYU-NI (1713-1781). One of the well-known Japanese woman haiku poets of the Edo period (1603-1868). A renga master who studied with the poet Yaha, a close disciple of Basho. After her husband died, she became a Buddhist nun, made a pilgrimage, and created her main work, Kohaku-an-shu — White Lake Hermitage Collection.

“air raids night after night”

clear stars

in the cold night

after the planes’ roar

ISHIBASHI HIDENO

THE HORROR and poignancy of war’s universal experience are expressed through a woman’s eyes in this haiku. Usually we get the experience of war through a male perspective, but there are some courageous women writers, such as Ishibashi Hideno, who lived through the bombings of Tokyo during World War II and simply documented her experience through haiku. It is only recently that non-Japanese are finally becoming aware of the war atrocities of more civilians being killed in the Tokyo and other cities’ bombings than in the combined atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Here in the midst of air raids, we get the human dimension: the resilient capacity of the human spirit under dire circumstances to be able to appreciate the crystal-clear stars on a freezing night, in the stillness after the roar of the planes diminishes . . . Then it is just the silent stars overhead and the eyes of a woman staring up into vast space, in awe of this almost terrible beauty that remains after the human destruction. Just clear stars and the sound of our own heartbeats: the sacred remains.

ISHIBASHI HIDENO (1909-1947) An outstanding Japanese woman haiku poet of modern times. From her youth she had famous teachers, including the haiku poet Kyoshi and the tanka poet Yosano Akiko. She later had haiku meetings with Yokumitsu Riichi. She was married to the renowned haiku critic Yamamoto Kenkichi. (1907-1988) and they had one daughter. Hideno died in Kyoto from tuberculosis and war trauma. Her one collection, Sakura Koku (Cherry Blossoms Deep) won the prestigious Kawabata Bosha Prize. Translations of her haiku can be found in Far from the Field: Haiku by Japanese Women, translated and edited by Ueda Makoto.