Mother pulls back covers, flings aside the rumpled futons, prods us with rough fingers. She wrenches my brother from sleep. I watch through slitted eyes. Today I start school.

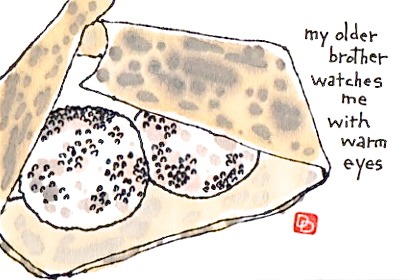

My heart slows, and I’m the last to the table. Mother says nothing, but she adds an egg to my millet gruel. My older brother watches me with warm eyes. He left school six months ago when Father could not leave his futon. Now he helps the other men collect pebbles to line the newly paved road outside the village. Father raised his voice that day, when Brother stopped going to school, like one crow’s squawk that rose with the smoke and dived back to his normal whisper. Brother looks away, pushes back from the table and takes a rice ball to wrap for lunch. One hand on my shoulder, and I know: I go for both of us.

The school building is not like our buildings. The windows glare down at me, and I cannot tell which one is the sacred window. I hurry inside with the others. They rush through the hallways, satchels bouncing on their backs as books and papers spill from their arms. I carry nothing. I take my empty hands to an empty seat. I sit on them. I recognize other Ainu among the Shamu. I shift my weight, burrow my hands deeper under my body. A man suddenly walks inside. Silence slams the door shut. He is tall, and his black hair flops across his forehead. As one eye, our eyes find our desks. He speaks.

Mother speaks only Japanese, except if she is singing the Songs. Huci, my grandmother, and Ekasi, my grandfather, spoke the old tongue, but they both joined the spirit world before I was born. I do not recognize what language this man speaks at first, and in surprise my eyes meet his. His black eyes hold mine, the only ones bobbing on the sea of dropped heads. I realize he is speaking Japanese after all. Now he calls the names of new students. He calls mine, Kaizawa Gensuke, and I copy the other students who raise their arms and shout out boldly. My voice breaks, but my back straightens. I forget about my empty hands as I listen to the rest of the names.

Students suddenly squirm, swooping down to take books out of their bags. I have nothing to take. An older student nudges his neighbor, another Shamu. “Inu-kun,” he whispers. Dog boy. Ainu sounds like inu, dog, to the Japanese. My hands creep down towards my knees. There is a noise behind me. The teacher stands, glaring.

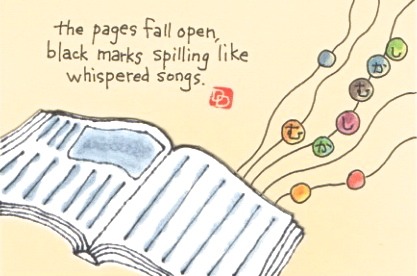

The boys open their books quickly. I wait, head dropped, twisting my empty hands further into hiding. The teacher places a book on my desk. The cover gleams as I blink. “I have a satchel you can use to carry it. Wait during recess.” The teacher’s voice murmurs like the river, like Father’s. Before Father died, he woke us with the old Songs, the fishermen with their long, carved boats, or the otter and the red-haired hag. I look up, surprised. The teacher nods, and then his voice booms, loud again: “Welcome, Gen-kun.” One of the boys shifts in his seat, and I know he’s heard. I touch the book lightly, my hands strong against the shiny cover. When I finally hold it, the pages fall open, black marks spilling like whispered songs. The book fills my hands.

Today I start school.

More of Deborah Davidson’s etegami can be found at her website: www.etegamibydosankodebbie.blogspot.jp/

Kris Kosaka, a resident of Japan since 1996, is a teacher and writer. Currently she works in Hokkaido and is completing her MFA in Creative Writing at the University of BC’s online program.

Etegami illustrations by Deborah Davidson