clear water is cool

fireflies vanish–

there’s nothing more

-Chiyo-ni 1703-1775; trs. Donegan & Ishibashi

[J]apanese haiku, the simple three-line form of poetry, is now the world’s most popular poetic form. Since it first became known in the West one hundred years ago, it has been seen from various perspectives. As a way to convey an aesthetic image, as a way to appreciate nature and as a way to record the Zen ah! moment. Perhaps it could also be seen as a means to appreciate “transience” — a way (or perhaps a practice) to enabling us understand and accept death in our ourselves and everything around us.

Haiku brings us the birth and death of each moment. Everything is stripped away to its naked state. No high tech speed, but slowly and naturally we discover what is simply here, as in meditation: our aging bodies, the afternoon light on the bed sheets, the sound of a siren in the distance. Whatever is contained in this very moment, without adornment. The Tibetan Book of the Dead talks about these momentary bardo states, states of transition from one realm to another, from life to death to re-birth. These states of transition also exist in each moment of our life when we are alive on this earth, each moment containing a mini-birth and mini-death. One result of the shock of September 11, 2001 is a greater recognition of this transience, on an individual, national and world level of consciousness.

Usually it takes a personal crisis such as a death or separation from a loved one to awaken this realization of our true human condition. It is really our inability to accept this impermanence that causes us to appreciate less and suffer more. As Pema Chödron, a Tibetan meditation teacher says, “… happiness lies in being able to relax with our true condition which is basically fleeting, dynamic, fluid, not in any way solid, not in any way permanent. It’s transient by nature…”

violets, grow here and there

in the ruins

of my burned house

—Shokyu-ni 1713-1781

However, in the midst of the speed of post-modern culture, we somehow miss this point. The effect of speed is that it ignores, denies or negates the natural process of life. For things take time to grow: a garden, a baby’s steps, the trust of a friend, the study of a map or the stars, even a good cup of coffee or tea. This was recently illustrated in a Japanese comic strip showing the making of a cup of Japanese tea: a hundred years ago, one hour to make and serve tea in tea-ceremony style; fifty years ago, fifteen to thirty minutes to boil water in a kettle and serve tea in a ceramic cup; twenty years ago, five minutes to steep a tea-bag from a hot-pot into a paper cup; ten years ago, five seconds to get a hot can of tea from a vending machine (See KJ 47, P. 91). Modern civilization’s evolution or ‘de-evolution’?

A speedy culture ignores natural laws. For through this unconscious addiction to speed and hyper-living, even in the simple act of drinking a cup of tea, the natural process of birth, growth, old age and death is given little attention. No part of this is escaped, but the process is missed. Any transformation emerging from reflection is bypassed. And without self-reflection, especially reflection of our mortality, we cannot really see ourselves or our world clearly. This is where haiku awareness can possibly bridge the gap — as a practice to be more conscious of these momentary states in our lives.

plucking my gray hairs—

beside my pillow

a cricket sounds

—Basho (1644-1694)

Haiku can be an antidote to the speed of post-modern culture — allowing one to step off the spinning wheel, to stop and breathe deeply and slowly. To note the birth and death of each moment. Whether we write it down, recording it in words, isn’t of ultimate importance, although it may be enjoyable for some. But rather, seeing things around us with ‘haiku eyes’ is of importance.

Haiku awareness can be a vehicle to help bring our attention back to the moment. Reading good traditional or modern haiku can give us a hint as to how to be more present. Haiku’s shortness, too, fits the short attention span of a speedy world. In fact, the process of tracing the rising and falling of this moment’s birth and death is built into this three line Japanese poetic form, which makes it one of the easiest art forms to use, in expanding this kind of awareness.

rising steam from the bath—

spring begins

on this moon-lit night

—Issa (1762-1826)

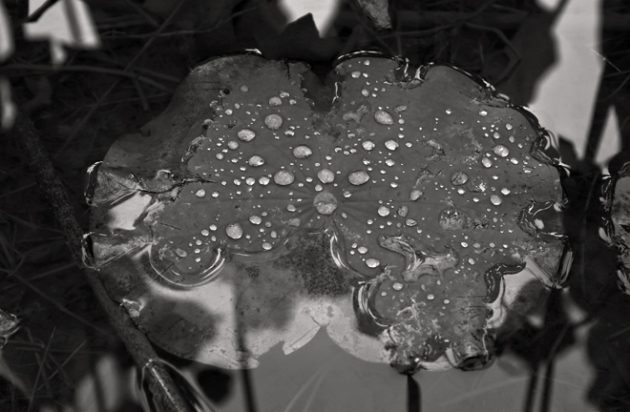

Expanding awareness means noticing what is already here in this time and space. Noticing for a few moments, perhaps only for as long as the count of 1, 2 or 3 breaths… Letting the thoughts and sensations of the moment’s sounds and images fade and new sensations arise. Perhaps noting the fading sunlight on the curtain… That moment dies and another is born; no need to catch it but just note its passing, as a thought in meditation, as in a last breath, as in the loss of something which becomes dearer because it’s fleeting.

This traditional Japanese life view, an acceptance of mujo or transience, is naturally embedded in haiku. This aesthetic in Japanese is known as mono no aware, which roughly translates as “the beauty of dying things” or “the beauty of transient things.” Rather than a traditional Western poetry of denial in ‘rage, rage against the dying of the light’ (Dylan Thomas) or ‘Death, thou shalt die.’ (John Donne), Japanese traditional poetry shows an acceptance and awe of the natural stages of becoming and disappearing in each thing. As in these haiku:

summer grasses—

the only remains

of warriors’ dreams

—Basho

good-bye…

I pass like all things

dew on the grass

—Banzan 1661-1730

the dead body —

autumn wind blows

through its nostrils

—Iida Dakotsu 1885-1962

And although it’s possible to find the opposite view in each tradition, nonetheless, these two views of acceptance and denial still pervade the cultures of the ‘East and West.’

[W]hether we ultimately deny or accept transience, the main thing is to note the passing of things. That in itself is transformative, for it forces us to slow down. For in the speed of modern culture, instead of using ‘saved time’ to be quiet, sit still and just be, as in slower less ‘high tech’ cultures, we instead do another thing — go to another appointment, travel a further distance, and wonder why we have ‘less time.’ Our modern litany is, ‘I don’t have enough time.’ Speed accelerates, draws us into the vortex, so instead of doing less we are doing more.

The speed of Western-style globalized culture has a dehumanizing effect. It ironically defeats our original purpose, to have more time to relax and enjoy the moment. Haiku may be a way to step out of this vortex, if only for a few moments a day. To write it down, or just stop and note the moment’s passing will inevitably force us to slow our pace, so that we can participate in the moment’s birth and death. It is essential for our survival, for even our health & sanity, but above all for our humanness.

I kill an ant

realize my children

have been watching

—Hekigodo

As I look up from writing down these thoughts about ‘haiku and transience’ in Zenpukuji park near my house in Tokyo, the autumn day turns to dusk. I note the pale gray light descending and shimmering in waves across the surface of the pond; the wild ducks floating in the dimming light. I note the stillness and the passing of the light in the ending of the day; the shouts of nearby children squealing with delight. The scene makes me wonder… the ducks or clouds don’t seem to be moving any faster than they did when I was a kid, or I imagine even a hundred years ago, but it is us human beings who are moving faster than is natural.

We are losing something vital, and we know it; we can feel it, an unbearable emptiness from loss. Empty because we are disconnecting from the slower rhythm of life around us, away from the slower pace of each moment’s passing. This disconnection seems to create a deep, unspeakable loneliness within us. And as we connect more and more to the instant-electronic net, we seem further and further disconnected from the natural net, the web of life. Ironically, in other eras when human beings were more connected to natural rhythms, they wrote haiku but didn’t need to use it, in the way we do today.

To relax with our true human condition which is itself transient, we must slow down enough to be aware, to feel the gap, the crack in the universe’s egg. For without seeing what is here, we are just speeding past and seeing very little. It reminds me of taking the shinkansen (bullet train) from Tokyo to Kyoto — it saves time, about three hours, but you see a blur instead of relaxing scenery; and in fact, one gets a headache if one stares out the window to see a view at all. We need to slow down, even for a few minutes, with whatever is in our sphere.

Breathing in and out with the ducks across the pond, breathing in and out with the rising and falling of the red maple branches, breathing in and out with the sick spouse or child sleeping next to us, just noting that… This is our heritage as a human being with all the other sentient beings on our planet. And haiku awareness in this post-modern era, can be a vehicle leading us, not back to another slower time which is virtually impossible, but back to this very moment, if just for a moment.

the first mists—

one mountain after another

unveiled

—Chiyo-ni