An impenetrable curse lay heavy on my heart. Call it an uneasiness, call it ill humors—like a hangover after drinking, you drink every day and there comes a time when it all might as well be a hangover. Well, that time had come. Not a particularly good state of affairs. The problem was not the resultant lung inflammation or shot nerves. Nor was it my grueling stack of debts. What was wrong was that curse. The most beautiful music I’d once enjoyed, even a single stanza of the most beautiful poem became too much for me to take. I’d make the effort to go listen to gramaphone records, but after only the first two or three phrases I’d feel like getting up to leave. Something wouldn’t let me stay put. And so I kept drifting ceaselessly from neighborhood to neighborhood.

For some reason, I remember being strongly attracted at the time to the beauty of shabby things. In scenery I liked run-down neighborhoods. And then not their mannered mainstreets, but the somehow more endearing backstreets where dingy laundry hung out to dry, junk lay scattered about and you peered in at real squalor. Neighborhoods eroded by wind and rain, slowly but surely returning to the soil, the crumbling earthen walls and sagging houses — where only the plants flourished, here an astonishing sunflower or patch of canna in full bloom.

Sometimes walking those streets unexpectedly I wouldn’t be in Kyoto, but in Sendai or Nagasaki hundreds of miles away from Kyoto —look what town I’m in now!— or at least I endeavored to foster the illusion. Were I able, I would have fled Kyoto and gone off to some town where I didn’t know a soul. For peace and quiet above all. A room in a deserted in. Clean futon. The nice smell of mosquito nets and starched yukata. A whole month or more I’d spend there lying about not thinking about anything. What I sought was for here to be that town for the space of a few hours. And as my illusions gradually grew more successful, I’d go from one thing to the next daubing on pigments of my own imaginings and the crumbling quarters. Wherein I took pleasure losing my real self.

I also discovered fireworks, those little wonders. Although the actual pyrotechnics were secondary to the cheap red and purple and yellow and blue painted wrappers, all kinds of striped sparklers by the bunch, Chuzanji Starfall, Battling Blossoms, Weeping Grasses. Then there were the rat-tail fire crackers all coiled up one by one and packed in a box. Things like that held strange sway over my heart.

Then too, I became fond of bidoro, those colored-glass skittle discs with lucky fish or flowers cast in relief, as I took a liking to Nanking marbles. Just to put them to my lips gave me indescribable delight. Is there any taste ever so faintly chilling as the taste of bidoro? When I was little my father and mother used to scold me for putting them in my mouth, so probably some hazy childhood recollection had come back bigger than ever to haunt me, but for the life of me I swear somehow there’s a briskly refreshing poetic savor to that taste.

As you will have surmised, I was utterly without money. Which is to say I needed even those few luxuries to console me by way of giving my heart a nudge. Items costing maybe two or three sen—these were luxuries. Beautiful things—tempting things that moreover came within range of my lethargic antennae —such things naturally comforted me.

Thus, among my favorite places, before my life corroded from under me, had been Maruzen Department Store. The red and yellow eau de cologne and eau de quinine. The stylishly crafted cut-glass and classic roccoco modelling of the amber and jade perfume bottles. Pipes, penknives. soaps. tobaccos. I could spend the better part of an hour just looking at them all. And then in the end splurge on maybe one pencil. But now the place was singularly depressing for me. The books, the students, the cashiers all shone in my eyes like the ghosts of bill collectors.

One morning after my friend had gone off to school — at the time I was in transit from place to place, staying with this friend, then that — I was left all alone in a vacuum. Once again I had to get out and wander. Something was driving me out. So from neighborhood to neighborhood, I walked those backstreets, pausing now before a candy shop, now gazing at the dried shrimp and pressed cod and soymilk flakes in a dry goods store, until finally I found myself heading down Teramachi toward Nijo where a fruitstand stopped me in my tracks. I should like to take a moment here to introduce this fruitstand, for out of all the merchants of my acquaintance this fruitstand was my absolute favorite. By no means a fancy shop, it nonetheless made you most plainly aware of the special beauty a fruit store possesses. The fruit was set out in rows on a steeply inclined display stand, the old shelves of which had seemingly once been lacquered in black. The fruit arrayed in such color, such volume as if frozen in place by some gorgon ‘s mask — a bright, beautiful allegro that turned onlookers to stone. The further recesses of the store were piled higher and higher with produce. And indeed the beauty of the carrot tops there was something to see. As well as the beans and arrowhead bulbs soaking in water.

The premises were particularly striking at night. Facing onto the hustle and bustle of Teramachi — an overstatement, really, the street is far more serene than any in Tokyo or Osaka – the display window poured out a flood of light. Yet for some reason, the immediate vicinity of the storefront was surprisingly dark. The location, with one side facing onto Nijo, was bound to be dark, still it was not clear why it should have been so despite the neighboring house on Teramachi. Although if the place hadn’t been dark I doubt it’d have proven so seductive to me. Another thing, the building bad deep-set eaves, like the brim of a cap pulled down to eye level — more than just a turn of phrase, it was enough to make you say “Hey, the brim of that shop’s cap is awfully low.” Everything above the awning was pitch black. So pitch black thereabouts, in fact, that there was nothing around to detract from that dazzling shower of light from the electric lamps strung along the storefront, the beautiful view, shining out from inside the store. Naked lamps sending out long slender screwthreads to pierce the eyes of passersby, seen through the glass wind ow upstairs at a lock shop nearby, the sight of that fruits and was one the few things on Teramachi that could occasionally move me.

That day I made a purchase at the store, something I’d never done. For it was rare to see lemons at that store. Now lemons are extremely common fare. But that store, not quite run-down merely your run-of-the-mill greengrocer, was like no place I had seen before. I was absolutely taken with that lemon. The color, pure and simple, like lemon yellow pigment straight out of the tube, solidified. And perfectly shaped like a squat weaving spindle. I decided to buy just one. Then where and how do you think I walked? I walked the streets for the longest time. I was out on the town, extremely happy, for the moment I grasped the lemon I sensed a slight easing of that curse so heavy on my heart. To think that this melancholy so pertinacious should have been diffused by something as simple as a piece of fruit- unthinkable, but paradoxically true. The heart is one strange and wonderful thing.

The chill to the touch of that lemon was indescribably nice. My lungs were in bad shape at the time and I always ran a fever. In fact I’ d make show of my fever to any and all friends. asking them to clasp hands. My hands would be hotter than anyone’s. May be because of this temperature, the sensation of chill penetrating throughout my body from my grasped palm was most pleasant.

Over and over again I kept bringing the fruit to my nose to take a whiff. Images of California, where it was grown, would come to mind. “It struck my nose,” a phrase that surfaced piecemeal from “The Citrus Seller” I’d studied in Chinese literature class. And when I took a deep breath, filling my chest with that fragrant air, the exhilaration that came over me —had I ever inhaled so deeply? – the warmth that rose to my face and limbs somehow awakened new health in my body…

Actually, I can hardly believe how the simple sensations of coolness and texture and scent and sight came together as if I’d been searching for just that all my life – incredible now, for it has become something “back then.”

A light, excited spring to my stride, I walked with a certain air of self-satisfaction reminiscent of the poet out stalking the streets in full aesthete’s garb . I’d set my treasure on a dirty handkerchief, hold it against my manteau, measure the reflectivity of color, and think —

So this is all it weighs.

That weight. That’s what I’d been forever seeking, that weight which without a doubt equated to all that was good, all that was beautiful. I myself had to laugh at so ridiculous a notion. Still and all, I was in bliss.

Just where and how I walked I have no idea, but in the end I found myself standing in front of Maruzen. Ordinarily I would have avoided the place at all costs, but that day it seemed positively inviting.

“What say we give it a look today?” And straight in I went.

Yet somehow or other, the cheery disposition that had filled my heart gradually dissipated. The perfume bottles, the pipes all failed to elicit any interest. Melancholy set in and just walking around became tiresome. I headed over to the art books. What an effort just to take those voluminous collected works down from the shelf! Never before had it taken so much strength. I’d pull out books one by one and open them up, but the concentration to turn the pages just wouldn’t come. Even more possessed, I’d go pull out yet the next book. And it’d be the same all over again. But still I wouldn’t be satisfied until I’d given it one quick look. And when I’d had all I could take, I just left it lying there. I couldn’t even put it back in its former place. This went on and on. Finally I came to that great orange volume of Ingres, an all-time favorite of mine, now so doubly unbearable I had to put it too aside. What spell was I under? This weariness lingering in the muscles of my hand. I became depressed surveying the mound of books I myself had pulled down.

Where were the art books that had once so captivated me? Hadn’t I used to relish that strange sense of displacement upon looking up from page after page to see such all-too-normal surroundings? …

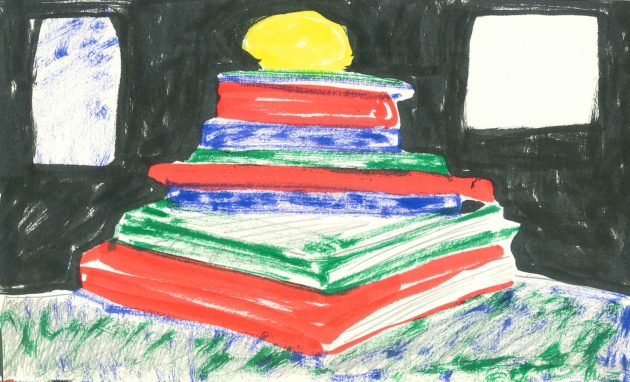

“Ah, but of course.” Just then I remembered the lemon in my kimono sleeve. Why not pile up a jumble of books of different colors and give the lemon a try to see how it looks? “Yes, of course ”

That light, excited air returned to me. I grabbed the nearest books at hand and began to pile them, here crushing them brusquely, here building a crude stack. Taking more new books down, taking others away as the crazy castle changed colors by turn, now redder, now more blue.

At last it was finished. Whereupon I stilled my pounding heart long enough to poise the lemon atop the castle parapet. The crowning touch.

Illustrations by Lauren Moya-Ford

www.laurenmoyaford.com Instagram: @laurenmofo

Kajii Motojiro distilled the dark spirit of an era into a few seminal works of short fiction. He spent the Taisho years drifting between his native Osaka, Kyoto and technical training in engineering, then Tokyo where he attended the English literature faculty of the Imperial University (present-day Tokyo University) and helped found the literary journal Blue Sky (Aozora) only to withdraw to Yugashima hot springs for a health-cure for his life-long lung ailments. A voracious reader of Western literature, Kajii is often created with having introduced a Berliner Luft and stream-of-consciousness into modern Japanese writing at a time when the rising tide of militarism was exerting pressures upon expressionistic and leftist writings.

The Japanese version of Lemon appears in Kajii Motojiro zenshu daiichikan published by Chikuma Shobo, 1980 (10th ed)

US-born Alfred Birnbaum was raised in Japan from age five. He studied at Waseda University and has been a freelance literary and cultural translator since 1980. Birnbaum’s works of translation include Haruki Murakami’s Hear the Wind Sing, Pinball, 1973, A Wild Sheep Chase, Dance Dance Dance and other works, Miyuki Miyabe’s All She Was Worth, and Natsuki Ikezawa’s A Burden of Flowers.

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013