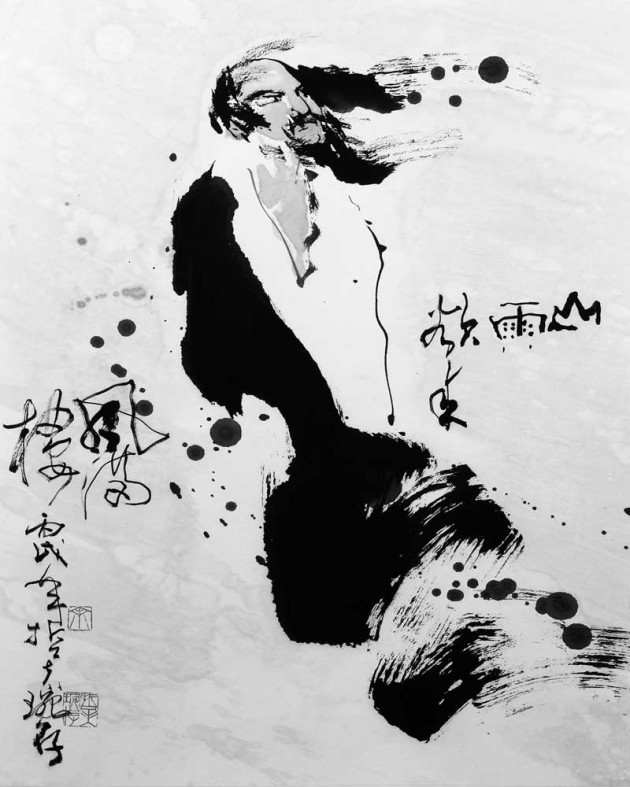

[T]he “Song of Tea” is one of the most beloved -poems known by tea-drinkers the world over. Its verses on “seven cups” of tea remain as famous today as when written in China during the T’ang dynasty (618–906 ad). The Song was composed by the poet Lu T’ung (775–835 ad), a Taoist recluse and connoisseur of tea. Lu T’ung was inspired by a gift of rare tea from one of his patrons, an official high in the ranks of the imperial court. The tea was named Yang-hsien, after the imperial estates where it was grown for the exclusive use of the emperor. Surprised and delighted by the special present, Lu T’ung brewed the tea and drank. Bowl after bowl, he felt the tea transform him until it seemed that he became immortal. The story of Lu T’ung provides a glimpse into the art of tea and the Taoist world that produced the “Song of Tea.”

Lu T’ung was a gentleman of leisure. Indeed, for all of his sixty years, he lived in retirement, realizing the literati dream of freedom from the dusty world to write and pursue artistic pastimes. Erudite and cultured, he was a poet of considerable eccentricity and a noted epicure of fine tea. For a time, he lived as a hermit in the mountains near the eastern capital. His lofty, independent style was admired far and wide by the wealthy and the powerful. While ministers and officials might fret and toil for rank and fortune, they could always look to Lu T’ung as the ideal among them, unsullied and beyond the fray. But such fame was unfortunate for a man devoted to reclusive life. Yet, Lu T’ung maintained a remarkably fine balance between his inner world and mundane society. And, the truth be told, his celebrity kept Lu T’ung in the highest company and in the rarest tea. Still, the farther from solitude he strayed, the closer he came to the imperial court and its lethal intrigues. In a knotted twist of fate, Lu T’ung’s passion for tea proved to be his undoing. His perfect life ended abruptly and very badly.

In the ninth century ad, tea was everywhere: from the palace to the cottage, from the northern and southern borders to beyond the eastern seas. Among the elite, tea was an aesthetic pursuit, an artistic and culinary endeavor that had been codified by the Ch’a-ching (Book of Tea). Published in 780 ad, the Ch’a-ching was a canonical work written by the great saint of tea, Lu Yü. Lu T’ung, who was no relation to the elder tea master, studied the Book and became expert as a connoisseur.

In the mind of Lu T’ung, the sage Lu Yü and the Ch’a-ching were models of the art of tea and eremitic Taoism. By a quirk of fate, Lu T’ung was born in Mount -Wangwu, one of the most sacred of Taoist places. The sanctity of his surroundings imbued Lu T’ung with a strong sense of the spiritual, and Taoism was deeply held by him all of his life, his poetry and tea a reflection of Taoist observance and teaching.

Lu T’ung practiced the art of tea in Stone Village where he lived in a country villa and called himself Master Jade Stream after a local mountain spring. Originally from Fangyang, Loyang, he was a member of an aristocratic clan of landed gentry; his status and means allowed him a life devoted to family and the aesthetic ideal. While on pilgrimage to Mount Sung, one of the five sacred mountains of Taoism, he stayed to live years in seclusion on Lesser Stone, a peak rising amidst the monastic sanctuaries that flourished on its slopes. Scholarship and study occupied his time between writing poetry and brewing tea. The time that passed was uneventful and full of peace.

While atop Mount Sung, Lu T’ung befriended Meng Chien, Advisor to the Heir Apparent. Meng belonged to an influential family and was also Grand Master of Remonstrance, an imperial advisor whose duty was to correct and admonish the emperor on policy and -matters of state. Lu T’ung’s literary prowess and unconventional manner impressed Meng Chien, and learning of the poet’s taste for tea, he favored Lu T’ung with gifts of the most expensive and exclusive caked teas. As a man of wealth and resourcefulness, the Grand Master could acquire any rare tea in the markets of the two capitals, Ch’angan and Loyang. However, imperial tea, especially the prized Yang-hsien, was beyond mere purchase. Made exclusively for the throne’s private use, no market carried it and no amount of gold or silver or copper cash could buy Yang-hsien tea. It could only be bestowed directly from the hand of the emperor. Under these circumstances, Meng Chien’s closeness to the throne was crucial: the Son of Heaven often pried advice from the Grand Master with gifts of imperial tea. On one such occasion, Meng Chien sent a generous share to Lu T’ung on Mount Sung.

Lu T’ung began the Song with a bit of self–mockery, describing himself as rudely awakened from a deep sleep at nearly midday. Unlike officials who rose before dawn to attend court, Lu T’ung let everyone know that he slept in and slept late. Moreover, he dreamt of the Duke of Chou, the virtuous minister of antiquity who loomed as an auspicious premonition of Meng Chien and his gift. The crashing reports at his gate alerted Lu T’ung to the martial presence of no ordinary courier, but a general and armed escort with a parcel and message direct from the Grand Master. The value of the package was signaled by its wrapping of sealed silk and the cover letter providing the exact count of its contents – all steps to foil pilfering. The precautions were warranted for the gift was quite extraordinary: three hundred round cakes of imperial tribute tea.

Lu T’ung was so surprised that he wondered out loud: “Such venerable tea is meant for princes and nobles; how did it reach the hut of this mountain hermit?” How indeed, for no one but the emperor had Yang-hsien tea. Grown on crown estates in the prefectures of Huchou and Ch’angchou near Lake T’ai, the tea was made from imperial reserves for the exclusive use of the throne. Tea came in the form of small wafers and cakes. The freshly picked leaves were steamed, ground into paste, and dried in moulds of different shapes: rounds, squares, and rectangles. In the Book of Tea, Lu Yü distinguished the tea from Huchou as “superior” and that from Ch’angchou as “next” in order of quality, but in every case he considered Yang-hsien a fine tea “with a lovely fragrance.” The tea was much admired by the emperor who ordered that the tea gardens of Huchou be established as an imperial -estate.

Yang-hsien was among the most symbolic tributes of the year, and it was anxiously awaited. Fresh and tender, the “pearly tea” appeared early, coaxed to sprout by gentle winds off the lake, the season nurturing “buds of golden yellow.” The tea was, therefore, the harbinger of spring for “the one hundred plants dare not bloom” until the emperor had the first taste of Yang-hsien tea. Yang-hsien also had great ritual and ceremonial importance. Immediately after the New Year, the prefect of Huchou ordered repairs to the road leading from the valley into the mountain to accommodate the laborers required for the harvest. Soon after, palace eunuchs arrived from the capital to direct the harvest as local officials planned the housing, provisioning, and care of the thousands of tea workers coming from the countryside. In the second lunar month, the tea was picked and quickly processed into cakes over just a few days followed by a week of special handling. The tea was carefully inspected and packaged, wrapped in fine white paper and bundled in soft silk satchels, then locked in lacquered cases.

It was imperative for the tea to arrive at the palace before Ch’ing-ming, the Festival of Purity and Brightness, on the fifth day of the third lunar month, the date fixed by tradition when the emperor honored his T’ang ancestors. Sent from Lake T’ai in the south to Ch’ang’an in the northwest, the bulk of the tea was conveyed up the Grand Canal to Loyang, overland through the Lan-t’ien Pass, and then again by boat to the capital. Once in the city, the tea was escorted to the inner palace. In the safety of the emperor’s private treasury, the tea was divided and a portion sent to the imperial family shrine to be offered in sacrifice to the ancestors of the dynasty. The rituals were performed by the emperor, who, on fulfilling his filial duties, returned to the palace where his tea master prepared Yang-hsien tea.

Far from Ch’ang’an on Lesser Stone Peak, Lu T’ung also celebrated the arrival of the season with Yang-hsien tea. On opening and admiring the three hundred cakes, he barred his gate and shut his doors to enjoy himself in solitude. Before preparing the tea, he made himself ready, donning his silk gauze cap, focusing on the task at hand, calmly concentrating on preparing and brewing the imperial tea. He listened for the first boil of the water and sighted bubbles the size of “fish eyes” followed by the second boil and its bubbly “string of pearls.” The surge of the third boil erupted with the measure of tea powder, then there ensued a quiet simmering as the tea brewed. Looking into the cauldron, Lu T’ung imagined the convecting tea to be “clouds of green yielding, unceasingly” blown by the “wind.” Ladling out a serving, Lu T’ung admired the fine, “radiantly white” froth floating lightly on the tea, the foam thickening as it clung and cooled against the bowl.

As a Taoist and tea connoisseur, Lu T’ung knew the delights of tea-drinking as well as the herbal effects of tea. In the “Song of Tea,” Lu T’ung described the physical sensations produced by three bowls of tea as the herbal decoction worked on his body and mind.

The first bowl moistens my lips and throat.

The second bowl banishes my loneliness and -melancholy.

The third bowl penetrates my withered entrails,

finding nothing except a literary core

of five thousand scrolls.

The stimulating and mood-changing effects of tea were already apparent to Lu T’ung after the second bowl, and with the third, his senses were elevated, his thoughts cerebral and inspired, and his mind flooded with his vast learning. With the prescribed three bowls of tea, Lu T’ung had reached the ultimate of the tea experience in both feeling and connoisseurship.

Remarkably, Lu T’ung continued drinking, taking several more bowls of tea, a thing against which Lu Yü in the Ch’a-ching strictly warned: “All of the best tasting tea is in the first and second bowls. The third bowl is next in quality. Fourth and fifth bowls of tea are excessive…one must not drink more.” But Lu T’ung raised the bowl again and experienced a further sequence of sensations that altered his body and spirit:

The fourth bowl raises a light perspiration,

casting life’s inequities out through my pores.

The fifth bowl purifies my flesh and bones.

The sixth bowl makes me one with the immortal, feathered spirits.

The seventh bowl I need not drink,

feeling only a pure wind rushing beneath

my wings.

With the sixth bowl, Lu T’ung exceeded Lu Yü’s prescription ignoring the tea master’s proscription against any more. Thus as a connoisseur, Lu T’ung greedily doubled his enjoyment of the imperial tea. But as a Taoist, he recalled the further words of Lu Yü: “In efficacy, tea rivals…sweet dew.” Tea was alchemical and compared to the celestial essence, the heavenly elixir of life. With tea’s herbal effects, Lu T’ung deliberately and radically transformed his powers of concentration and perception, creating a transcendent state.

As Lu T’ung was about to drink an extraordinary seventh bowl, he felt a “pure wind” beneath wings that lofted and sent him flying. Airborne, he left the last bowl behind as he soared as a feathered spirit searching instinctively for the fabled mountain of P’englai, the Taoist isle of the immortals, a distant and mystical place somewhere in the Eastern Sea yet beyond the phenomenal world. Then literally remembering himself by his sobriquet, “Master Jade Stream,” he inclined instead for Huchou and the earthly tea mountain to join the “other immortals…protecting the pure, high places from wind and rain” to nurture the imperial gardens of Yang-hsien tea. As he mused about the tea plants, he was suddenly struck by a great pang of conscience and Taoist charity. Crying aloud, he bemoaned “the bitter fate of the myriad peasants toiling beneath the tumbled tea cliffs!” Realizing the human cost of tea, his flight of fancy abruptly faded, displaced by a desire to know of any relief for the tea workers. In his letter of thanks to Meng Chien, Lu T’ung flattered the minister, obliquely comparing Meng to the righteous Duke of Chou of antiquity, hoping to stir the man’s moral senses and gain some small assurance from his generous patron.

It is unknown what moved Lu T’ung to abandon his solitude on Lesser Stone Peak. But he descended from his mountain hermitage and entered the old city of Loyang. Known as the Eastern Capital, Loyang was the official city and residence of the crown prince and a major market and entrepôt of the empire. Lu T’ung arrived in Loyang a celebrity. He owed his fame in part to the lunar spectacle of 810 ad and his long, intricate prose poem entitled “Eclipse of the Moon” that commemorated the wintry scene of ice and cold when the midmonth moon and its radiant light were gradually dimmed. He engaged society at the highest levels, repected and welcomed in the homes of the powerful for his profound aesthetic sense and keen connoisseurship of tea.

For the next twenty-five years, Lu T’ung avidly pursued his poetry and tea. But, his unbridled fondness for tea led unexpectedly to his complete and utter destruction. In 835 ad, the emperor attempted to assassinate the palace eunuchs who had taken control of the throne and government. The plot failed, and in terrible revenge the eunuchs killed eleven ministers, hundreds of officials, and thousands of their friends and families in the disasterous event known as the “Sweet Dew Incident.” For centuries, the Incident served as a stern warning to all emperors and ministers against the power of eunuchs. The caveat extended to everyone, even to poets and tea connoisseurs whose innocuous, cultural pastimes might nonetheless get them killed.

Grand Master Meng Chien having passed away long ago, Lu T’ung had gravitated to yet another patron, the emperor’s most hated minister. Living as an honored guest in the minister’s mansion, Lu T’ung was unaware of the danger. Indiscriminate in their vengeance, the eunuchs arrested the innocent but hapless poet. Imprisoned and tortured, Lu T’ung was later executed and buried in a paltry grave.

Through the ages, Lu T’ung was all but forgotten. Traces of his writing were preserved in later anthologies and a few prose poems survived, most notably the “Song of Tea.” It is perhaps fitting that the Song endures as his most famous poem. In some consolation to his spirit, Lu T’ung’s brilliant verse on seven wondrous bowls continues to be sung in the minds of tea drinkers to this day. And at each silent singing, Master Jade Stream remains immortal and soaring above the tea lands, winging away to the far and mystic Isles of Mount P’englai.

Astonished by the magnitude of the gift, Lu T’ung wrote a letter in the form of a poem to Meng Chien, thanking him for the exceptionally rare imperial tea. Originally entitled “Writing Thanks to Imperial Grand Master of Remonstrance Meng for Sending New Tea,” the poem became simply known as the “Song of Tea”:

The sun is as high as a ten-foot measure and five; I am deep asleep.

The general bangs at the gate loud enough to scare the Duke of Chou!

He announces that the Grand Master sends a letter;

the white silk cover is triple stamped.

Breaking the vermillion seals, I imagine the Grand Master himself

inspecting these three hundred moon-shaped tea cakes.

He heard that within the tea mountain a path was cut at the New Year, sending insects rising excitedly on the spring wind.

As the emperor waits to taste Yang-hsien tea,

the one hundred plants dare not bloom.

Benevolent breezes intimately embrace pearly tea sprouts,

the early spring coaxing out buds of golden yellow.

Picked fresh, fired till fragrant, then packed and sealed:

tea’s essence and goodness is preserved.

Such venerable tea is meant for princes and nobles;

how did it reach the hut of this mountain hermit?

The brushwood gate is closed against vulgar visitors;

all alone, I don my gauze cap, brewing and tasting the tea.

Clouds of green yielding; unceasingly, the wind blows;

radiantly white, floating tea froth congeals against the bowl.

The first bowl moistens my lips and throat.

The second bowl banishes my loneliness and melancholy.

The third bowl penetrates my withered entrails,

finding nothing except a literary core of five thousand scrolls.

The fourth bowl raises a light perspiration,

casting life’s inequities out through my pores.

The fifth bowl purifies my flesh and bones.

The sixth bowl makes me one with the immortal, feathered spirits.

The seventh bowl I need not drink,

feeling only a pure wind rushing beneath my wings.

Where are the immortal isles of Mount P’englai?

I, Master Jade Stream, wish instead to ride this pure wind back

To the tea mountain where other immortals gather to oversee

the land, protecting the pure, high places from wind and rain.

Yet, how can I bear knowing the bitter fate of the myriad peasants toiling beneath the tumbled tea cliffs!

I have but to ask Grand Master Meng about them;

whether they can ever regain some peace.

©Steven D. Owyoung, used with permission. A longer version of this article is available at http://chado.blogspot.com