A light rain is falling, cooling off the sultry heat of early summer in Kyoto. As I walk up the stone pathway to Torin-in, I can just make out the fragile blossoms of the sarasôju tree on the other side of the wall. Before going inside the temple, I remove my shoes and fold up the paper umbrella, leaving it in the stand in the entryway next to the others.

folding up

my paper umbrella

closed petals

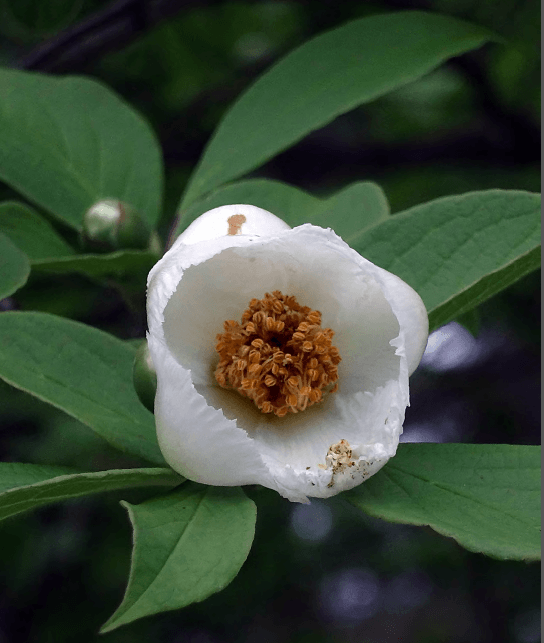

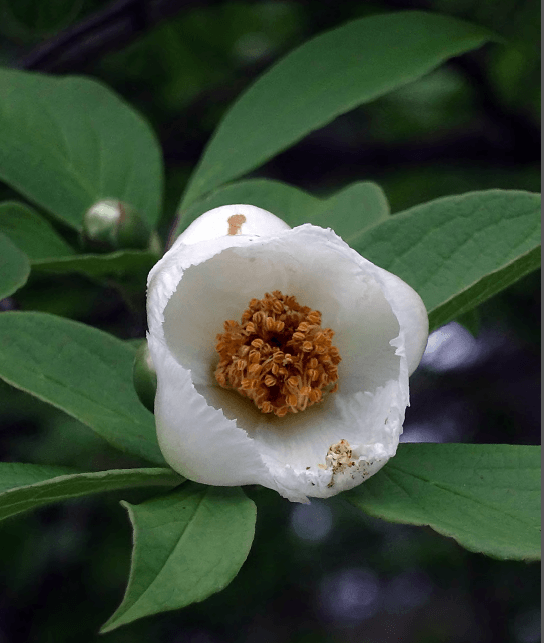

I walk across the tatami mat room and sit in a far corner, away from the flock of Japanese women who are exclaiming “Kirei, ne!” Beautiful!. We have all come here to enjoy the transient beauty of the sarasôju, some of us more vocally than others.

sarasôju blossoms

in the morning

shining with dew

in the evening

moldering

The sound of rain is refreshing, but it is weighing down the delicate flowers.

moment by moment

rain loosens their hold

on the mother tree

They fall softly on the moss, one by one. I watch them, lost in reverie. Suddenly I am startled by a deep croaking sound—and then another. At the same time, my eyes fill with the blue of hydrangeas.

beyond the temple wall

a bullfrog croaks

blue, blue ajisai

Then the brown-eared bulbuls join in with their raucous chorus. In ancient Japanese poetry, they are called hiyodori, a much more romantic name. Their heavy gray bodies shake the branches of the sarasôju tree.

noisy bulbuls

suck nectar from flowers

that live only one day

Flapping their wings and fighting for the exotic nectar,

the irreverent birds

knock down the flowers

before their time

trying to guess

which flower

will drop off next

The falling blossoms carry my eyes downward to the display on the moss. Their arrangement looks suspiciously like the photograph on the pamphlet taken last year. I imagine the head priest or gardener rearranging the blossoms every morning before the temple opens.

spaced so evenly

did they really fall randomly

from the branches

In the grayness of the afternoon, the white of the sarasôju is so bright and the moss luxuriantly green. My eyes stray to the wall with its restful patina of age; it reminds me of my favorite wall at Ryoan-ji Temple.

rain-soaked moss

on the temple wall

a blush of rust

From the wall composed of many rocks, I focus on a single rock in the garden, which is unusual because of its elegant boat-like shape.

sarasôju fall

hollows in the rock

fill with rain

Each blossom has fallen at a different time today. Those fallen early this morning are already brown, others are browning at the edges and the most recent ones still look fresh.

in different stages

of decay, yet

each one perfect

The temple priest rings the bell to indicate that it’s closing time. Looking around, I am surprised to discover that I am the only one there, completely absorbed in this garden of impermanence.

closing time

but waiting for my blossom

to

fall

Note: When the Buddha died, there were two sarasoju (sal) trees growing at each of the cardinal points surrounding his bier. A cutting from one of these was brought to Kyoto and planted in a small garden at Torin-in Temple where it blooms every year in early July.

Previously published in Hermitage Journal (Romania) c. 1999; republished with permission.

Margaret Chula lived in Japan for twelve years where she taught English and creative writing at universities in Kyoto. Her books include Grinding my ink (Haiku Society of America Book Award); This Moment; Shadow Lines (with Rich Youmans); Always Filling, Always Full; and The Smell of Rust.

Margaret lives in Portland, Oregon, where she continues to teach and give work- shops at universities, poetry societies and Zen centers.