“…some turbulence…fasten your seatbelts…”

I jolted awake as the world suddenly shook and stared, uncomprehending, at the black screen and plastic tray in front of me before remembering where I was. For a moment, I was gripped by panic, then I held up my hands in front of me. They were smooth and a uniform, pale beige.

I breathed a sigh of relief. I can keep shapeshifting while sleeping – all trolls can – but normally I change into a mossy rock or an old log or tree stump; not a human woman. It’s also harder to maintain another shape when you’re tired, and I was so, so tired. Elated with my success and amazed at seeing the clouds from above, I’d been certain that I’d be wide awake all the way to Tokyo, but somewhere over Russia, exhaustion had gotten the upper hand. I’d had so many new and stressful experiences already: stealing Nina’s passport, using her computer to buy the plane ticket, then assuming her shape to take the train and navigate the airport. But I had made it, and now I was quite possibly the first troll ever to fly on an airplane.

I would quite possibly also be the only troll ever to do so; there weren’t many of us left. I was the only female troll left in Sweden after my mum, Trollmor, died, and there were only two males: Torlov from Långfjället and Gamlefar. Gamlefar, my great-great-grandfather, was ancient and closed off to the world. He did nothing but sleep and would keep sleeping until one day, his body would turn completely into stone, leaving behind a mossy, vaguely troll-shaped boulder.

Torlov wasn’t much better company. He hated everyone and everything and had no interest in finding others like us. At least, I assumed that was the case; I had tried to suggest it the last time I saw him, but he clubbed me over the head, then threw rocks while roaring at me to get the hell out of his mountain. Grumpy fuck. No, Torlov and Gamlefar hardly counted. It was lonely being a troll in Sweden.

I shook off these sombre thoughts, reminding myself of my destination. Japan was covered with mountains and rivers chock full of oknytt – supernatural beings – though they called them yōkai over there. There were just as many different kinds as there had once been in Sweden, the rivers and mountains and forests teeming with different species, and I had studied day and night for years so that I’d be able to speak with them once I found them.

Nina was a young human woman who sometimes stayed in a cabin at the edge of my forest. The cabin belonged to her parents, but they came less and less as they got older, while Nina came alone to stay for weeks at a time. She was a “back‑end developer”, whatever that was, and she spent all day in front of a laptop – these little machines had been popping up everywhere the last few decades – typing and talking to people through the screen.

When she first started coming to the cabin, I’d go there and peek in through the window. Then, I began to sneak in behind her into the cabin, or sit down with her on the veranda, transforming myself into a stack of firewood or a rolled-up rag-rug. It’s not that I wanted to befriend her – there was too much baggage between humans and trolls for me to even entertain the idea – but it felt a little bit better to be near someone, even a human, than being truly alone.

Plus, she had Netflix.

When Nina finished talking and typing for the day, she would curl up on the couch and watch Netflix for hours, and I would watch with her, hidden in plain sight in a corner of the cabin. Most of it was human stuff of no consequence to me, but it was at least more entertaining than staring at a leaf float down a creek or watching the wild boar rummaging in the forest for the millionth time.

Then one day, she began watching Yōkai World, a show about the mythical creatures of Japan. I sat up ramrod straight, transfixed, and only when the first episode ended did I remember that a pile of firewood isn’t supposed to sit up straight. I resumed an appropriately piley appearance. Nina’s head had jerked at the movement and she turned to look into the dark corners of the cabin, fixing me with her stare just long enough to make me anxious – but finally, she turned back to the screen and put on the next episode, to my great joy and relief.

After that, I stayed in the cabin even after Nina had gone to sleep each night. I borrowed her computer to watch the show again and again, and crept up as close to her as I could when she worked in the daytime until I had figured out how to use the laptop to type things in and learn about them; googling them, as Nina said. In the nighttime, I read all about yōkai and the place called Japan, and I found it existed for real. The yōkai were supposedly mythical, but humans nowadays claimed that I was mythical, too, so I didn’t put much stock into that.

I began learning about Japan. I watched everything related to Japan there was on Netflix; my favourite was an old show from the eighties called Shōgun. I memorized all the lines in Japanese in it. “Ugoku na” – don’t move; “Dōmo, Toranaga-sama” – thank you, Lord Toranaga; “Tadachi ni jigai wo seneba naran to mōshite imasu” – he says he must commit suicide immediately. Then I began to study Japanese in earnest, and to learn how humans travel. If ever I got a chance, I intended to be prepared.

And now, that chance had finally come. Two days ago, Nina had arrived at the cabin, tanned and carrying a suitcase instead of her usual gym bag, and over the phone, she had told her parents about how she’d almost missed her flight from Bangkok. I didn’t know where Bangkok was, but it sounded far away – and that, I had learned, meant she probably had her passport with her.

I found it in the night, along with her credit card. I had watched her buying train tickets and ordering protein powder from the Amazon more times than I could count, but I could still hardly believe it when it worked. Somehow, with a little plastic card, I had gotten myself a return ticket to Japan: country of yōkai.

I was glued to the window from the beginning of the descent to Tokyo until the plane hit the ground, feeling like I’d boil over from terror and anticipation and nervousness and excitement. I wanted to run off the plane and towards those mountains, but first, I had to go through “immigration.” I was glad for the opportunity to practice my Japanese in real life before meeting with any yōkai, though – after all, I’d never spoken Japanese with another living being before – and was almost disappointed at the brevity of my interaction with the passport control man, who seemed uninclined to make much conversation.

I managed to find a train that was heading north and installed myself comfortably. The train shot off like a bullet, but despite the speed, we never seemed to get outside of the city; Tokyo must’ve been the size of a hundred Stockholms. When the city finally turned into suburbs and the suburbs began to be interspersed with rice paddies, a man in a uniform and white gloves entered the train car and began to verify tickets.

Tickets. In my exhaustion and excitement, I had forgotten about that. I got flustered and briefly considered shape-shifting into a tree stub, then realized a tree stub on a train seat might, on the contrary, attract attention. Instead, I dug out a tiny nugget of gold from my knapsack; I figured it should be adequate payment for the fine train ride.

I held it out to the conductor, but he didn’t make any motion to take it. “It’s gold,” I said, though it ought to have been obvious.

The man stared at the nugget, then at me. “Is that so?” he said, politely. “But can you please show me your ticket?”

When it turned out they wouldn’t take gold and that I couldn’t pay, I was asked to deboard the train at the next stop, where the station master would decide what to do with me. As soon as I got on the platform, I shapeshifted into a wolf – the knapsack with my gold and my passport on my back – and made a run for it past a shrieking crowd, then dove into a ditch and shapeshifted into a tree-branch, staying there until I knew I was safe.

I continued on foot after that, traveling over mountains whenever possible, taking on the shape of a wolverine or fox and running along rice paddies when not, avoiding the big cities that fascinated but frightened me. And oh, how many mountains there was! I was drunk with delight when I stood on the top of Mount Kamuro, mountains ridges covered with cedar trees as far as the eye could see. In a valley a little way off, I saw something blink and disappear. I set off towards it, confident that I’d find a Japanese cousin of the lyktgubbe, the will-o’-wisp “lantern men” that used to haunt the peripheries of farms in Sweden.

When I reached the valley and found it empty, I shrugged it off – lyktgubbar had been notorious for blinking out of existence, too – and continued on my way.

But the next valley and the next mountain peak were empty, too. Mountain after mountain, forest after forest, lake after lake: they were all empty of oknytt. I encountered hikers, monks, foxes, racoons, deer, wild boar, and one shabby-looking wolf, but no non-human, non‑animal creatures. No one I could talk to. And for each new magical-looking grove, mossy boulder, or hollow tree trunk that turned out to be just that, I lost a little more hope.

Dark thoughts began to haunt me.

What if there were no real oknytt in Japan? What if they were all just made up?

What if I had travelled these thousands of kilometres all for nothing?

What if I was truly alone in the world?

At the northern tip of Honshu, I found a mountain covered with ancient beech trees. Glimpsing what looked like the entrance to a shrine, I set course for it. I liked the little shrines and temples dotting the mountains and forests of Japan. There was nothing like it in Sweden; churches were always in human settlements. Perhaps Christianity’s hatred for my ilk had extended to the forests and mountains where we lived.

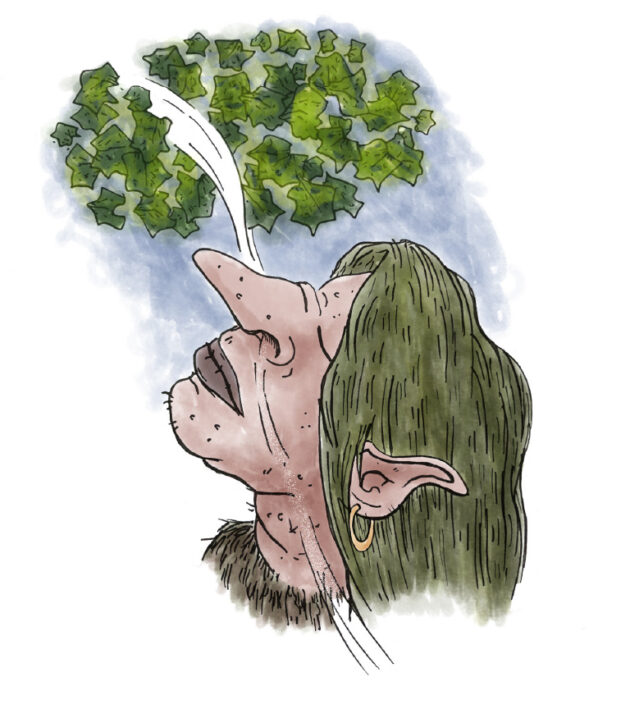

When I reached the shrine, I sat down on a stone bench and looked around. The moss‑covered stone lanterns and dark, damp wood of the altar and gates made the shrine look as if it was a natural outgrowth from the mountain, just like the ferns and beech trees. I looked up at the sunlight filtering in through the leaves, then closed my eyes and inhaled deeply. The scent of chlorophyll and humus filled my nostrils. It smelt like home. If only I hadn’t been all alone, I would’ve loved this island.

But I was alone. Still alone.

Always alone.

I wiped my eyes roughly with the backs of my hands, then jumped down from the bench. The beauty of my surroundings seemed only to mock me. There was nothing for me here. I would go back to my own forest, where I belonged, and then I would just have to resign myself to loneliness and the pretend‑companionship with humans who weren’t even aware of my existence.

My hands balled into fists and my eyes fixed on the ground, I stomped down the mountain, full of rage and blinded by tears.

I made my way back to Tokyo with three weeks to spare before my return flight. It was exhausting to have to maintain human form all the time, but I couldn’t face more time alone in yet another beautiful but lifeless mountain or forest. Besides, Tokyo intrigued me. It was so big, it made even Stockholm seem like a dinky village, and it was full of shiny things. The city itself looked like a big shiny thing, with skyscrapers like giant, glittering silver swords poking up from the ground.

With my keen sense for the smell of gold, I sniffed my way to a back-alley pawn shop where I sold one of the gold nuggets I had brought from home, happy to get a chance to talk about gold – one of my favourite things – in Japanese. I left with a nice, thick stack of yen notes and set about exploring the city.

I wandered the electronic megastores with rows of smartphones that looked like tiny slabs of shiny black onyx, and the watch shops in Ginza with all that delicate tiny machinery plated in silver and gold, and the fashion shops in Harajuku full of glittering jewellery. That jewellery was fake, of course, but it sparkled nicely. I filled a shopping basket with it and put it all on as soon as I had left the store, weighing down my earlobes with dozens of sparkling pink hearts and stars and ribbons, layering necklaces and bracelets around my neck and wrists until they resembled thick ropes of jewels, and fastening glittering hairpins all over my head until even my greedy little troll-heart was satisfied with the effect.

And the best part? When I emerged laden in fake treasure, there were no suspicious looks. Most people on the big shopping street didn’t notice me at all, and those who did (a group of young women dressed like Victorian children in poofy dresses and bonnets) were only appreciative, exclaiming “Kawaii!” in chorus. In fact, Tokyo was so full of people, and some of them were so weird-looking, that I almost thought people wouldn’t notice if I just walked around like myself, without bothering to shapeshift.

When I wasn’t looking at shiny things, I was eating. Trolls can get by on blueberries and pine sap and fish in the forest, but it isn’t anyone’s preferred food – we like roasted meat and ale and bread – and after three weeks in unfamiliar wilderness, I was starved for real food. I’m not really an adventurous eater – when I was little, Trollmor hade to bribe me with pieces of glittering pyrite to get me to eat the roasted dormice – but I was too hungry for any inhibitions. Some of what I tried was frankly repellent (that watery excuse for beer they called Asahi and balls of cold rice – gag), but some wouldn’t have been out of place at the great troll feasts of legend. I ate plates upon plates of thinly sliced sashimi that tasted so fresh, the fish must surely have been caught only moments earlier; breaded, fried pork cutlets that even the old Norse gods would’ve approved of; and matcha ice cream with a fresh, grassy taste, like a snow storm and a summer meadow rolled into one.

For a few days, I happily ate like a troll queen and admired shiny things, but once my eyes and stomach were sated, my exhaustion caught up with me. Looking for a place to get a drink, I stumbled upon a narrow alleyway full of tiny bars, but most were invitation-only or already full, and I kept getting turned away. I was starting to get annoyed when I saw an old man in a crisp black waistcoat and bow-tie standing in a doorway, motioning for me to come his way.

The old man’s bar was small and dark and smelled of oiled wood and liquor. It seated only five patrons, and three of the seats were already taken: two by middle-aged men in black suits and ties – they seemed to be the labourers of Tokyo – and one by a heavily made-up woman in a bright red minidress that clung to her voluptuous body.

I took the seat furthest inside, leaving an empty space next to me, and pointed to a bottle behind the counter at random. While the old man prepared my drink, I noticed the glamorous woman looking at me from underneath long, fake lashes. I was still wearing my Harajuku haul of hundreds of glittering earrings and hairpins and necklaces, so I figured she was just envious, but then she winked at me and licked her lips lasciviously.

Good lord.

The barman presented me with an oddly shaped bottle and a tiny cup. I drank and was surprised to find its contents were warm, and sweet, and liquory. Oh, this was lovely. This made up for that awful beer.

I poured myself another cup of the sweet liquor and downed it, too. Ah, I had needed this. So many new experiences and so much walking and I wasn’t half as good at Japanese as I had thought I was and I had been shapeshifting for three days straight – longer than I’d ever maintained another form in one go before. I had worked hard.

And accomplished nothing, a voice in the back of my head whispered.

I felt acutely sad. It was true. I hadn’t accomplished anything (well, except to acquire a kilo of fake treasure). I was still all alone and thousands of kilometres from my forest and I hadn’t found so much as a hint of a nonhuman creature to talk to on this island. Dammit. Dammit dammit dammit. Damn it all to that shitty area of Lapland where even the reindeer won’t go.

I drained another few cups of the sweet liquor, then found the bottle was empty. I held it up and gave it a little shake, and the barman soon brought me another one. I set about emptying it, too, systematically.

The world was rocking back and forth as if I was on a boat. I opened my eyes and a wave of nausea washed over me, then gave way. In front of me was a tiny porcelain cup and a bowl of tiny dried fish and my own gnarly, mossy hands. For a moment, I wondered where I was, then I looked up and saw the old barman, polishing a glass and taking no notice of me. Ah; the bar. I must’ve nodded off.

Something niggled at the back of my mind. I looked back down at the bar counter, at my gnarly, mossy hands. Shit. Shit shit shit shit shit.

I resumed Nina’s form, my hands turning smooth and mossless. My heart beat wildly. I must’ve stopped shapeshifting at some point after I got drunk or when I fell asleep – but when? Had it been long enough for anyone to see me? I glanced around the bar. The old barman was polishing away – he must’ve been in his dotage to be so inattentive – and the only other customer still at the counter was an aging suit who was clearly oblivious to everything but his whisky and his own personal misery.

I’d barely had time to register relief, however, when I heard a sultry voice behind me. “Mind if I sit down?”

It was the woman in the red minidress. She plopped into the seat next to me without waiting for my response, then reached out and poked my hand. “You looked more interesting when you were covered with chiirui. Can you show me again?”

I didn’t know that word, but I had a bad feeling about this. “What does chiirui mean?”

She poked my hand again with a long acrylic nail. “The stuff that was all over your hands and arms! Now how would do you say that… oh, let me check.” She pulled out a smartphone from a tiny purse. “What language do you speak?”

“Swedish,” I said faintly, cold sweat making my chest and face feel clammy.

The woman didn’t seem to notice my discomfort. “Swedish! You’ll have to tell me all about how it is over there. Give me a sec and I’ll look it up… isn’t modern technology marvellous? Oh, here we go. ‘Lavar.’ Is that how you say it? Lichen. Or maybe it was koge?” It was another word I didn’t know, but she typed it into her phone, too. “Mossa”, she announced with a little shake of her wrist that made her bracelets jangle. She put the emphasis on the wrong syllable, but I got what she meant.

“Yes, it’s mostly moss.” I said quietly. “Though there’s some chi… something, too, on my back.”

“Chiirui.” She smiled and nestled an arm around me. “Oh, don’t look like you’ve been caught committing a crime when you were just being yourself for a bit.” She removed her arm. “In fact, you’re one hell of a lucky girl.”

“How so?” I asked.

“Because you met me!” she exclaimed, spreading her arms wide and beaming.

I stared at her, unimpressed.

Then, with a poof, the voluptuous woman was gone, and in her place was…a – a giant beaver? An otter? I was so startled I almost fell of my chair.

“What the—”

“Ta-daaa!” said the oversized, big-bellied rodent on the bar stool. It wore a straw hat but was otherwise naked. A grubby paw clutched the stem of a leaf.

“You’re… are you… what…” I stammered, not managing to string together a question.

“I’m a tanuki,” the big rodent exclaimed, waving the leaf excitedly.

A tanuki. I remembered now; they had appeared on Yōkai World. They were racoon dogs who could shapeshift. I seemed to remember they had giant balls that they could use as drums or an umbrella when it was raining – that fact had stuck – but this one had no balls.

“Helloo-ooooo?” said the ball-less tanuki, waving a paw in front of my face.

In my state of tipsy stupefaction, I had again forgotten we were in public, but at her paw‑waving, it came back to me. I glanced toward the suit, but he was out cold, his head on the bar counter. The barman was polishing a glass, miraculously seeming to be unaware of the pudgy, oversized racoon dog next to me. “Hey, should you really look like that here?” I whispered, motioning with my head towards him.

“Oh, he’s too professional to remark on his clients’ appearance,” the tanuki said. “But if you insist,” she added, perhaps noticing how freaked out I was. She placed the leaf she had been waving on her head, then with another poof, she was back to white skin and generous cleavage and jangling bracelets.

The barman held up a glass towards the light, checking it for any spots, ostentatiously ignoring us.

“So, what are you?” the tanuki-woman said, tapping an acrylic nail against my hand.

“I’m a troll,” I whispered. “And I’ve been looking for you for weeks. Or someone like you, I mean.” All my fear and disappointment and loneliness from the past few weeks welled up, then morphed into anger. Suddenly, I was furious at the tanuki, showing up so blithe and unconcerned after I had been so desperate and miserable. “I walked and walked and walked and searched all over the forests and mountains and rivers and rice paddies. I didn’t even see a hint of – of our type,” I hissed. “Nothing. I started to believe you were all made up. I started to believe I really was all…”

The tanuki-woman cut me off. “Forests and mountains,” she said, snorting derisively. “Have you never heard of ‘urbanization,’ dear? Or ‘rural depopulation’? Forests and mountains – pah! Of course you didn’t find anyone. I can’t understand why anyone would want to be all alone in the mountains where they can’t even get a decent drink or katsu curry.”

The truth of her words began to sink in. “I can’t understand it either,” I said after a moment, quietly. “That’s why I came all the way here from Sweden. There was no one else there; I was all alone.”

The disdain on the woman’s face dissipated. “Oh!” she exclaimed. “Oh.”

She reached out and put her hand over mine, and for just a moment, the manicured nails shifted into nubby little claws and the white hand into a furry paw. She smiled. “I know a place to go.”

After we left the bar, Mariko – that was her name – took me to a club. It was just like the ones I’d seen on Nina’s Netflix shows, with flashing lights, people in glittery outfits, drinking and dancing and a deafening untz-untz-untz… except the people were all yōkai, and I was asked to un-shapeshift at the door. Mariko introduced me to demon-bear onikuma, two-tailed cat spirit nekomata, long-nosed tengu demons, and a self-sufficient male tanuki, who without my prompting – or desire – demonstrated how he could use his oversized scrotum as a drum set. Some of these yōkai were friendly and asked me questions about Sweden, while others acknowledged me politely but seemed entirely uninterested in me. The latter made my eyes sting with tears: not because I was hurt, but because of the unexpected joy at discovering a place where being an oknytt was so accepted, so commonplace, that it didn’t even stir curiosity.

We stayed at the club till long after dawn, then Mariko and I snuck into the Shinjuku Gyoen park, where she had a burrow underneath an elm tree. The burrow was cluttered with bags of snacks and beer cans and comic books but nevertheless cozy. For the first time in weeks, I went to sleep without shapeshifting, staying as my trollish self and sleeping like the dead until late in the afternoon.

The remaining weeks of my trip, I spent every moment with Mariko. We drank together, ate together, sang karaoke together, went shopping in Harajuku together. We went back to the yōkai club a couple of times and to a yōkai coffee shop underneath the train station in Ueno, but I didn’t feel any strong urge to meet more people; I was happy just to spend time with her.

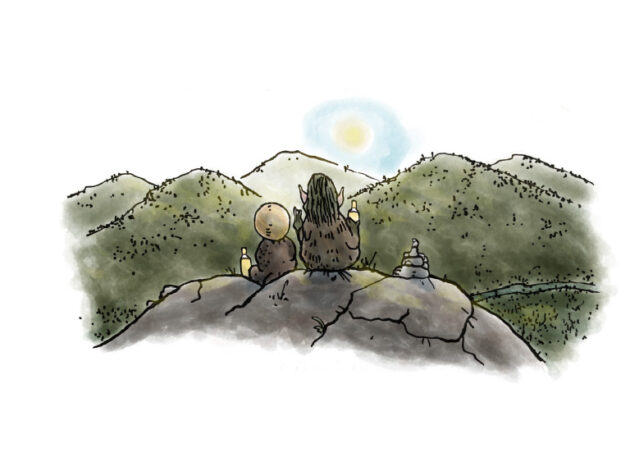

After I told her that, we agreed to leave Tokyo for a few days. We climbed Mount Takao with backpacks full of beer and sandwiches, finally settling on its summit to look out over Tokyo. I told Mariko about my forest at home and about the animals: the reindeer and wolverines up north, the deer and boar and occasional moose of my forests. Mariko wanted to see a moose, and when we returned to Tokyo, we scoured the zoos in search for one. None were to be found, but we had fun anyways.

It was the day of my return. To the last, I had avoided thinking about it, but there it was. I would’ve loved to extend my trip, but the longer I was away, the greater the risk that Nina would once again need her passport, discover it was gone, and have it reported. The thought of leaving was painful, but I swatted away the pain, telling myself to focus on preparing for the trip, and that surely, I’d be able to come back some day.

Packing was quick. I hadn’t bought anything but the jewellery and a fabulous lamé jumpsuit I’d found in Shibuya; I was wearing the jumpsuit and most of the jewellery, and the rest I stuffed into my knapsack. I went outside to fetch the pouch with the passport and my gold, which I had hidden under an oak near the burrow. I crouched down by the tree and groped for it underneath the roots, soon feeling the smooth plastic surface. I pulled it out, dusted off the soil, and opened it – then froze.

Nina’s passport was gone.

I reached into the space underneath the root again, groping blindly, but there was nothing but clumps of soil and stringy roots. And I knew it couldn’t have slipped out, anyways; the pouch was closed with a zipper. Someone must have taken it. But why didn’t they take any of the gold? And how did they find the pouch? It was well hidden, and I only went to get gold after the park’s closing, when there was no one but Mariko within a five-hundred-meter radius.

Mariko.

Pouch in hand, I stomped back into the burrow, where Mariko was lying on her futon, reading manga. I stood there, fuming, until she looked up. “Is something wrong?”

“My passport is missing,” I said between clenched teeth.

“Is that important?” she asked, innocent-looking.

For a moment, I became uncertain – but no, Mariko wasn’t as clueless as she acted. Nevertheless, I decided to answer the question at face value. I fought to keep my voice level. “Yes. It’s important. Without it, they won’t let me on the flight tonight. And the longer I’m gone, the more likely it is that Nina will notice her passport is gone and go to the police. And then, even if I find the passport, it won’t be usable anymore. And then I’ll be stuck here. Forever.”

Mariko’s large, round eyes got larger and rounder as I spoke. Then she jumped up from the futon, clenching a tiny, furry fist to her heart. “We shall scour Shinjuku Gyoen for this ‘passport’,” she announced solemnly. “We shall leave no root, no vending machine, no rose bush untouched. And if yet we fail to find it, then we shall build a BOAT. We will use cedar and pine and we shall make a great sail, and even should it take a decade – no, even should it take ten decades, you shall see the majestic moose of the Swedish forests again, and…”

My surprise at the impromptu monologue momentarily calmed my rage. Suddenly, I recalled the ending of Shōgun, where Lord Toranaga orders Blackthorne’s ship to be burned, stranding him in Japan.

“Anjin-san, my friend, it is your karma never to leave this land,” I quoted.

“What?” Mariko said.

“Nothing.”

She took a deep breath, apparently about to resume her oration, but I held up my hand to stop her.

“Wait. I need to think.”

I took a slow, deep breath while silently counting to ten. I didn’t want my fury at having a decision forced upon me blind me to the right decision.

Going back to Sweden today just because I had a ticket would’ve been an act of inertia, I realized; the trip warranted more thought. There was no guarantee I’d be able to cross country borders again. It had been a gamble the first time around, and I may very well get stuck in Sweden – or worse. Who knows what would happen to a paperless troll caught committing identity theft? At any rate, I might never see Japan again. Just like if I stayed, I might never see Sweden again.

I thought of the little rivulet near my cave; of the scent of resin and humus and decaying wood in my forest; of the pattern of the lichen on my favourite boulder. Then I thought of the cedar-tree-covered mountains I had hiked through in Japan; of Tokyo, which despite the tens of millions of humans inhabiting it paradoxically still allowed me to be – very nearly – myself; of drinking beer in front of the TV with Mariko.

I looked down at Mariko. Paused in her monologue, she had a faux-serious expression: the face of a puckish tanuki putting on a show for laughs. But that, too, was a veneer. Her eyes were darting anxiously over my face, and her whiskers were trembling.

The last of my fury melted away, then, and I could see clearly. The thought of perhaps never again seeing Sweden was painful. But the thought of never again seeing Japan, of never again seeing Mariko, was far worse.

“Forget about the passport,” I said. “I’m going to stay.”

“Really?” Mariko asked, her eyes round.

“Really,” I said. “This is where I want to be. I’ll miss my forest, eventually, but I have no life there. This is my new home.”

The expression on Mariko’s face was worth a hundred passports; never in my long life had anyone looked so happy at the prospect of my presence. I scrunched up my face in a grimace to prevent myself from crying. It was ugly, but Mariko didn’t see it anyways. She had thrown her furry forearms around my hips and was hugging me tight, her face buried in my stomach. I returned the hug as much as our height difference allowed, resting my mossy hands on the fur on her back, and relaxed my face, allowing tears to trickle down my cheeks.

Four months later, we finally found a moose, in the Kanazawa Zoological Gardens. He was lying down and munching on some twigs in a small enclosure: a far cry from the vast forests of Sweden. I was underwhelmed, almost embarrassed, but Mariko was ecstatic. We had snuck in after hours and stopped shapeshifting as soon as we were out of human sight, so she was scurrying back and forth around the enclosure in her oversized racoon-dog form.

”He’s so big! He’s like, five times the size of a deer! No, ten times a deer! I bet his head is bigger than I am. Are there really animals like this running wild in Sweden?”

“Yes,” I said. “In the northern half of the country. I only get – got – the occasional one by my forest.”

Mariko stopped her scurrying. She hesitated, then asked, “Do you miss it?”

“A little, sometimes, but I don’t regret staying, and I doubt I ever will.”

She let out a sigh of relief. “Good.”

We watched the moose eat for a bit, then I asked, “Hey, Mariko… Could I have my passport back?”

The soft, furry body froze, making her look like the tanuki statues that adorn the entryways to Japanese bars. But surely, she knew that I knew she had taken it?

“I’m not planning on going anywhere,” I added, to be clear. “I just want it as a memento of my journey.”

Mariko, still looking stiff, scratched her neck with her paw. “Well, see, I don’t have it anymore. I sold it on the black market.”

“You sold it on the black market.”

“Yeah.”

Of course she bloody sold it on the black market. I took a deep breath, torn between laughter and anger, then looked down at my hands, mossy and sparkling with dozens of rings and bracelets like a lake in the sunshine. The sight of my jewellery always made me calmer.

“But I didn’t use the money,” Mariko said defensively, stomping her foot on the ground. “Well…not all of it, that is. I did use some of it to pay for the takoyaki maker.”

Ah, the takoyaki maker. It had been a misguided impulse buy; it was annoying to clean and we had only used it once. Perhaps it was fitting that the passport was converted into something equally purposeless.

“But I didn’t use the rest of the money,” Mariko said, clinging to her defence. “It’s in one of the crevices under the TV at home. I’ll give it to you when we’re back.”

I shook my head, exasperated. “Just put it in our snack fund.”

As we watched the moose munching on its tree branch, I felt Mariko’s paw sneak into my hand. I squeezed it, then nodded in the direction of a forest we had passed on our way to the zoo.

“Hey, how about we set this guy free in the forest over there?”

From the corner of my eye, I saw Mariko’s whiskers rising as she grinned. “Let’s do it.”

ALICE NORD grew up in Sweden and now splits her time between Japan and France. She writes fiction in the early mornings before her day job as a medical writer and translator. Her work has appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, Jelly Bucket, Andromeda Spaceways Magazine, and BlazeVOX. She can be found on Instagram and her website.

ALEX MANKIEWICZ is a Kyoto-based illustrator and artist, specialising in graphic narrative. When the World Was Soft: Creation Stories of the Yindjibarndi (Allen & Unwin) was published April 2024. @alexmango1

‘Never to Leave This Land’ first appeared in KJ 108 (Fluidity 2) in 2024.