Marilou looked out over the condominium pool. The surface of the water lay still, unbroken. Hard glass like the surface of the Lims’ living room table that she cleaned after every meal. Usually, even at this time of the night, there would be a couple of swimmers doing laps. Working off their dinner. Not anymore. Everyone was too scared of community spread to use any of the common facilities. The only movement below her was a middle-aged man jogging along the footpath, a lone wind-up action figure patrolling the circumference of the estate.

Was Joriz alright? Marilou’s son, back home in the Philippines, was just fifteen. Still a boy, no matter how much he liked to think of himself as grown-up. He had fallen off his bicycle a couple of days ago, fallen badly. Nothing critical, her husband, Crisanto, had assured her; thank God. But a broken leg. This was a difficult time to seek medical help, the number of COVID cases in Sorsogon still high. Fortunately, her sister-in-law was a nurse, and able to help make the necessary arrangements.

Marilou was over two thousand kilometres away in Singapore. Unable to return home. Nothing she could do. Except worry. Bad enough that her parents were both in the most vulnerable age group; and now Joriz.

And what about the hospital bills?

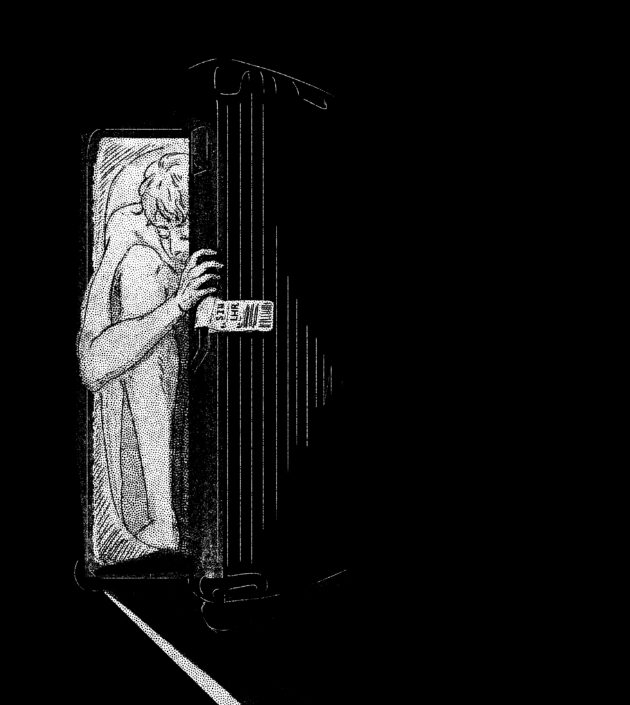

She rested her arms, thick and fleshy, on the top of the half-wall, and cupped her face in her hands. Marilou often stood in the balcony at night to gather her thoughts. To take in the breeze, survey the expanse of the property, with its sprawling gardens, tennis courts, and playgrounds. Her room behind the kitchen was a square box with cream-coloured walls. It had barely enough space for a single bed and a cupboard. Twelve years in Singapore as a helper, and she had never really gotten used to the fact that her room here did not have any windows. In Sorsogon, her family lived by the sea. Here, when she closed the door, she felt like she was in an underground bunker, even though she was seven storeys above ground.

It was even worse now that she was not permitted to take days off. In fact, she was not allowed to leave the apartment at all, except to go downstairs to wash the car, or accompany Mrs Lim to the market. She could no longer meet her friends. Every Sunday, they would lay out their picnic mat in the Botanic Gardens, enjoy the sun on their faces. But Mrs Lim wasn’t comfortable with her going out anymore. Paid her extra as compensation. For the last few months, she had been restricted entirely to FaceTime conversations in her room.

Words weren’t enough, though. What she yearned for was a concerned hand on her elbow, an arm around her shoulders. Just a simple hug, she had lamented to her best friend, Aurelia, over the phone. The only two people who could possibly fulfil that longing right now were Mr and Mrs Lim. Not really an option.

Marilou sighed, shifting her weight from one foot to the other, pushing the air in her lungs out into the dark sky above. If only she too could float away. She had always missed home, of course, but she had drawn strength from her conviction that the sacrifice was worth it. Joriz was bright, doing well in Junior High School. He aspired to become a doctor. If she had not come to work in Singapore, it would have been impossible to pay for his education. Or build the house her extended family now lived in. Not on what she and her husband had been earning, as a cook and a seafarer. She just wished that the sacrifice had been hers alone. That her son did not have to grow up over the last decade only seeing his mother once every two years.

And it was going to be more than two years this time, wasn’t it? Her eyes were wet, her vision blurring. All these new travel restrictions. In fact, she had no idea when she would ever be able to see her family again. The new phone she had bought for Joriz’s birthday lay unwrapped in her cupboard.

Hundreds of thousands of people around the world had lost their jobs, had lost friends and family members to this virus. Missing home was such a small thing in comparison.

And yet.

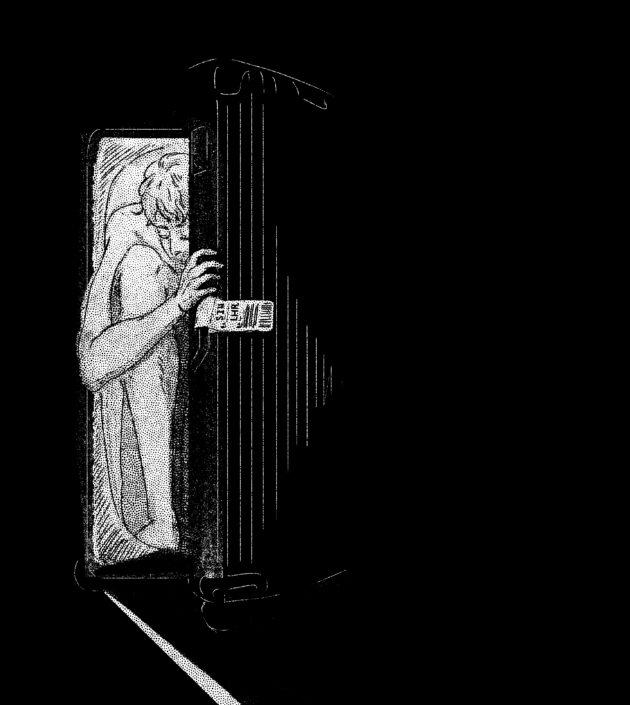

The clattering of keys, the opening of the front door. Her employers had returned from the airport. She dabbed at her eyes, grateful for the distraction. Behind the couple was their son, hauling his suitcase in tow. Darren was twenty-two now. His head was bowed low. He had an unruly nest of hair that had not seen a barber in a long time. He was also paler than she remembered, and rake thin. Like he had been living off salad the last two years studying in England. Just lettuce and cucumbers.

Never mind. He was back now. She had prepared his favourite curry chicken with potatoes. Drumsticks, of course. She had also cooked the rice with coconut milk and pandan leaves, exactly the way he liked it. She hoped he would smell the chilli and lemongrass the moment he stepped through the door. That the fragrance would remind him of home. Or, at least, what home was like before the incident with his father.

Darren wrestled with his luggage as he hoisted it up the small step at the threshold of the flat. With one violent jerk, the leather behemoth finally crossed the threshold, its wheels scraping across the marble tiles.

“Hi, Mari, good to see you again,” he said with the slightest hint of a British accent. His head was slightly raised towards her. Because of his facemask, only his eyes were visible. She was sad to see that there was no happiness in them. No shine, no life. Where was the precocious little wonder-boy she had first encountered all those years ago?

Maybe it was jetlag. At least he remembered his manners. Darren had always been extremely polite.

“Welcome home. You had a good flight back?”

Darren did not reply. He dragged his suitcase across the living room into his old bedroom as if he had never gone away. As if this were a route he still took every day. The bedroom door clicked shut behind him.

Mr Lim removed his mask and placed it on the ledge by the window together with his car key.

“We’ll eat later.”

His wife sat down at the living room table, opening the mail she had collected on their way home. With her mask still on and letter opener in hand, Mrs Lim looked like she was performing surgery on the envelopes. Her husband, a large bull of a man, settled into the sofa. He unbuttoned his shirt to release the weight of his belly and unfolded the newspapers on the coffee table. Neither said a word as they read, an expanse of space between them.

Marilou was used to their silence. She returned to her room, the rice cooker in the kitchen left on Keep Warm.

***

Mr and Mrs Lim were now always at home, tapping away at their keyboards or taking Zoom calls. Marilou had become accustomed to having the whole apartment to herself when her employers were at work. Not that she had boyfriends to bring round, unlike Aurelia who would get up to all sorts whenever her Sir and Ma’am were out of the country. Marilou was a married woman, after all, and a mother—though she could not deny the occasional temptation. Some of the young men who invited themselves over to the Sunday potluck picnics she shared with her friends were not bad-looking. They were easy to talk to and made her laugh. She enjoyed their company. No, what she missed was simply the freedom to put her phone on speaker, and chat with her friends and family as she dusted, swept, mopped, wiped and polished. Or to play her favourite Filipino and Rihanna songs as she cooked dinner, and waited for the Lims to come home. Now the flat had to be quiet as a church during the day as well.

It didn’t help that the Lims were clearly self-conscious about her doing her chores around them, vacuuming the rug around their feet, or perching on the tabletop beside them to reach the top of the windows for cleaning. Once, she had to crawl under Mr Lim’s chair while he was sitting on it to get to the other side. She was not embarrassed in the least. She was just doing her job. But husband and wife clearly would have preferred for all the housework to have been magically done out of sight, rather than to sit there sipping coffee while someone toiled around them. Well, what could she do about that? Not clean? She wouldn’t have minded kicking back and having a hot drink too!—something she used to be able to do whenever she liked. Now she finished her work as quickly as she could, then retired to her room to make video calls or watch YouTube clips. She was a guest in this home that, she was reminded starkly now, had never really been hers.

If she had held the faintest hope that having Darren back would change the dynamics in the flat, she was soon disappointed. The young man could not leave home for two weeks due to his quarantine notice, but he kept himself locked in his room all day. Sometimes she forgot he had even come back to Singapore. He usually took his meals in his room by himself. When he did join his parents, he would sullenly read off his phone or iPad as he ate, the family like three strangers sharing a table at a hawker centre.

She suspected that she may well have never seen Darren again if the campus shutdown had not forced his return. He would have found some excuse to stay on in England after what had happened. Complete his Masters, maybe his PhD. Find a job there. Anything to delay coming back. She knew his parents had not reached out to him over the last two years. Neither had he reached out to them. There had been no return trips, no parcels. No phone calls, no FaceTime. Maybe emails, but unlikely. Mrs Lim would have mentioned something to her.

Not that she needed to. There was very little that went on in the flat that Marilou did not know.

Two years ago, Marilou had returned from her day off. Even through the closed front door, she could hear Mr Lim’s raised voice. She fumbled with her keys. When she entered the flat, she saw Darren cowering on the floor, his face a contortion of tears and snot. His father towered above him, his fist clenched. Darren had one hand to his mouth, and Marilou could see that he was bleeding from the nose and lip.

No son of mine, Marilou heard Mr Lim say, before Mrs Lim scuttled over and frantically tried to shove her through to the kitchen.

“It’s nothing,” her employer said. “Go to your room.”

Marilou was short and squat, but strong from all the cleaning she did each day. She held her ground against the slender arms of the crane-like woman pushing at her to leave.

“But Ma’am, Sir is hurting him.”

“Mari! Go to your room now!” Mr Lim bellowed in a voice louder than she had ever heard before.

But how could she abandon the boy? Yes, her place in the Lim household was a matter of employment. Still, she had seen Darren every morning and evening. She had cooked for him, cleaned up after him. She had made sure he woke up on time, that his breakfast was always ready. She had ironed his school (then army) uniform, dusted his Chess Club trophies. She had spent more hours, weeks, months, years in the presence of this boy – this someone else’s child – than her own.

Before she could take a step towards him, however, Darren managed to bring himself to his feet, hold himself upright, even as his body continued to sway from side to side. He locked eyes with his father, then his mother. For a moment, Marilou thought he would charge at his father, though the young man had half his father’s heft.

Instead, he gathered himself, and spoke calmly and firmly: “I have done nothing to be ashamed of.”

“What you are doing is a sin,” his mother cried from across the room. Her fingers tightened around Marilou’s arms, her nails digging half-moons into the woman’s skin.

“And that matters more to you than your own son’s happiness?” he asked. Marilou thought there was a tilt of his chin upwards, a defiance. A standing of his ground against everything thrashing down on him.

And then Darren turned on his heels, and staggered towards his bedroom. He tottered as if he were just coming round after having been knocked senseless, which may well have been the case.

After that evening, the family hardly spoke to one another. Even the relationship between the couple had changed. Marilou’s employers had never been particularly affectionate towards each other, but there was now a coldness. Like there had been a death, and a heavy pall still hung over them. And then a few weeks later, after completing his national service, Darren had left for Oxford. What should have been the proudest day in the Lim family had simply felt like relief. A reprieve from the tension that arose whenever parent and child were in the same room.

No one told Marilou what had caused the fight to break out, but, of course, she already knew. A year before the incident, she had been airing out the boy’s winter clothes, getting his suitcase ready for a school trip to Europe. She had found a small cardboard box at the back of his closet. Was this where he kept his travel toiletries, she wondered as she lifted the cover. But there were no pocket-sized shampoos or tubes of lip balm inside. Just books and magazines. With pictures—and not of women. She wasn’t entirely surprised. After school sometimes, a boy would come over to the Lim household when both Darren’s parents weren’t around. One of Darren’s junior college friends. He had an egg-shaped face, big, eager eyes behind rimless glasses, and was all hello, aunty and thank you, aunty as she served them milo and sandwiches. She had her suspicions about what they were doing alone in Darren’s bedroom.

Naturally, she had kept silent. This was between Darren and his parents, and between him and God. She would not say anything, no matter how much she herself was uncomfortable with such behaviour. Like the Lims, she was a staunch Catholic. The church had a clear position on this matter. What if it were my own son, she had asked herself the day she had found the box, before forcing the question out of her mind, and returning to her chores. No, no use thinking of such things.

But she had called Joriz that night, and was relieved when her son, thirteen, happened to mention there was a girl whom he had his eye on.

Marilou stirred the pot of red bean soup simmering on the stove. It was clear that her employers were not intending to confront the issue again. Through the walls of Darren’s room, she could hear the muffled thuds of whatever music he was listening to. Mr Lim was taking groceries to his parents. Though it was a Sunday, his wife was in the living room working on her laptop. Even when forced to live together, the family had managed to stay apart. Meanwhile, all Marilou wanted was to be with her son again.

God could be cruel.

God also helped those who helped themselves. She checked her phone again – no, still no messages from Joriz since this morning – and then scooped a large helping of the steaming broth into a porcelain bowl. Red bean soup with longans was another one of Darren’s favourites, a local staple that, she was sure, would have been impossible to find in a campus cafeteria in England.

She brought the dish over to her employer on a lacquered tray decorated with a simple batik design.

“Ma’am?”

“What?” Mrs Lim asked, still fixed on her laptop screen.

“You want to bring the soup to Darren, Ma’am?” She had been counting down the days. Tomorrow would be the last of Darren’s quarantine. There was no telling what Darren would do when the order was lifted. When he was free to leave the apartment. She knew how headstrong he could be. Someone had to make the first move.

Mrs Lim looked at Marilou dumbfounded, as if her domestic helper had started speaking in tongues.

“Just knock on his door,” she replied brusquely, returning to her laptop screen. “And tell him it’s in the kitchen. He can help himself.”

Marilou steeled herself.

“I think it would mean a lot to him if you brought it to him,” she added, speaking woman to woman, mother to mother. She hoped it would be enough.

Mrs Lim’s fingers paused over the keyboard. She closed her eyes, leaned back in her chair, and took a deep breath in. And out, her body shuddering from the effort. When she finally opened her eyes, Marilou could see a redness, the start of tears.

Had she been counting the days as well?

“What you must think of this family,” her employer said as she rose from her chair. Marilou could not read her tone. Mrs Lim took the tray from her helper and crossed the living room to her son’s bedroom.

Marilou watched as the woman hesitated, then balanced the tray on one hand, and knocked on the door with the knuckles of the other. Marilou’s heart surged with desperate hoping. It took both parties to compromise, to give each other a chance.

“Son, you want some red bean soup?”

No reply.

“Son?”

Another awful period of waiting. A few seconds that seemed so long. But then, “Okay,” and the door slowly opening.

A few minutes later, however, as Marilou was checking her phone for calls from home in-between stacking plates in the drying rack, she saw Mrs Lim leave Darren’s room, her hand over her mouth. Her employer was struggling to compose herself. Her face was blotchy with red. She had been crying. She was still crying. And Marilou knew that she had made a mistake.

***

The next morning, Marilou knocked on the door of Darren’s room, and turned the handle to enter. It was ten-thirty. Their pre-arranged time every two days for cleaning. The young man was lying in his sleeping attire on the striped green and white sheets of his bed, his iPad open in front of him. He didn’t look like he had slept well. She was tempted to bring up what had happened the day before, but she wasn’t sure how to begin. So she simply accepted his mumbled greeting, and started to tidy the room without a word.

Besides, there was someone else on her mind. Joriz had still not returned her texts. Maybe something had happened. Some complication the doctors had missed? Perhaps he had fallen trying to move around on his own in his room. Or was it something even more serious? She could have called her husband or parents, of course. But Crisanto would have scolded her for over-reacting. It had not even been twenty-four hours.

And yet, hadn’t it only taken a second for her son to be flung off his bicycle headlong into the dirt road?

Or was Joriz not responding because he was angry with her? For not being there when he needed her? He had every right to be. This wasn’t the first time. It was her husband’s sister who had been taking care of him all these years. She was the one who had thrown him his birthday party last week, who had stood behind him with her hand on his shoulder in the family photographs. She was the one who would be taking care of Joriz now.

Sunlight was streaming in through the large sliding windows of the room. In the background, a Taylor Swift song she recognised because Aurelia was always playing it. Marilou wanted to get out of the room, message Joriz again. She was just about to leave, a small load of used t-shirts, shorts and boxer briefs under her right arm, when he asked, “How’s your family doing?”

It wasn’t the first time he had raised this question since he had returned. She knew he was genuinely concerned, not asking for the sake of asking.

“They are all okay,” she replied, though saying the words was difficult when there was a part of her still consumed with worry. No, stop it, she told herself. Stop being so paranoid.

“What’s it like in The Philippines?” he continued. “It’s pretty bad back home in the UK.”

“Some parts more than others,” she said, trying to focus her attention on the conversation. “I have some friends in Singapore who have lost people in their family.”

“Oh, I’m sorry. Are these older relatives?”

“Yes.”

“And your friends, they can’t go back for the funeral?”

“No, we don’t know if Singapore will let them come back in after that.”

“Yeah, well, I’d be more than happy to never come back here if I could,” he said, his attention returning to his iPad, his index finger swiping across the screen.

She felt her throat tighten. His room was scented with lemongrass from a diffuser on his bedside table, and she was suddenly conscious of its fragrance thick in the air. She paused at the door, and asked, “Are you going to go away?”

“Go where?”

“I was afraid you would move out again.”

“None of my friends’ parents will let me stay with them. And I don’t have any money for my own place.”

Of course. She had been so naïve. It had always seemed like the Lims could do anything they wanted. But she had no reason to be concerned. For all his bravado, he remained dependent on his parents. They were still the ones paying for his education overseas. Putting a roof over his head, food in his mouth. Despite everything he had put them through.

That was what parents did. Put their child first. No matter what.

“You know your parents love you?”

He didn’t say anything. He kept his eyes cast down on his iPad, but she knew he was listening.

Perhaps she could salvage the situation?

“I saw your mother come into your room yesterday.”

Still silence.

“She missed you when you were overseas.”

“She said that she was sorry.”

“That’s good, right?” she asked. “So what is the problem?”

“Because I’m not sorry.”

Marilou held his dirty clothes tight against her body. She felt a strange weakness in her knees, a hollowness behind her belly button. Like she hadn’t had breakfast. Hadn’t eaten in days.

“I don’t accept her apology,” he continued, his gaze still focused on his iPad, like he was talking to himself. “She stood there and let everything happen. I will never forgive the both of them. I can’t wait till I start working. I will pay back every single cent they ever spent on me, and then I never want to talk to either of them again.”

He moved his head to face the windows as if planning an escape.

“I fucking hate that I have to stay here with them.”

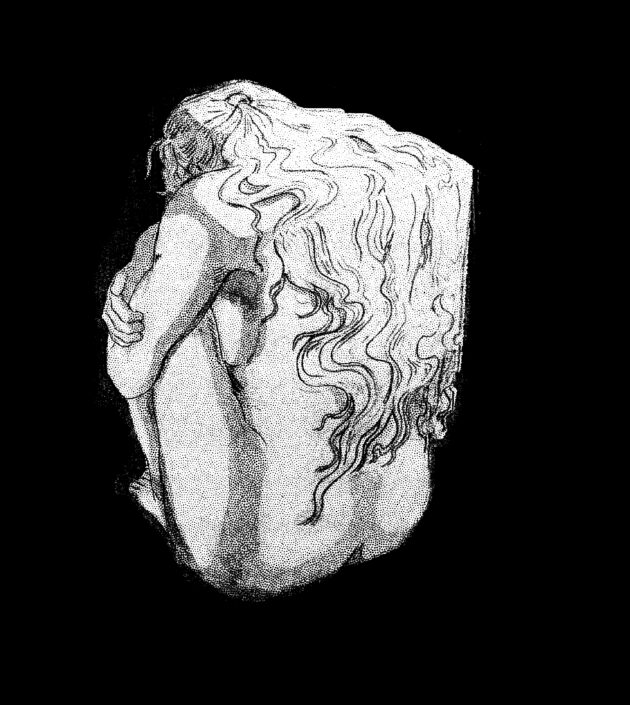

Marilou could not hold back her tears. They burst out of her in violent sobs, her whole frame wracked with convulsions. Her body had lost all its strength, was turning inside out, emptying itself of everything she had. She missed her family, wanted to be with her husband and son, her father, her mother. And every time the image of any of them appeared in her head, another wave of guilt and sadness and longing swelled within her, crashed through her defences, made it difficult to breathe.

Like she was drowning. Drowning on dry land, so far away from home.

This silly, silly boy. Did he not know how lucky he was?

She suddenly felt the urge to hit him. To smack him across the face.

“Mari? Are you okay?” Darren asked, springing towards her.

She could not answer him. Only curl herself into a ball, try to become as small as she possibly could, as she felt the walls of the room continue to press in on her.

Tomorrow. Tomorrow would be another day, but, she knew, no different from this one.

Five of Ken Lye’s short plays have been performed in Singapore, and his short stories have appeared in Quarterly Literary Review Singapore and the recent Singapore at Home: Life Across Lines anthology. He completed his MA in Creative Writing in 2019, and is currently working on his first novel. See also: www.literaryshanghai.com/ken-lye-the-last-dance/

Suzu (Supakarn Masunthasuwan) is a Thai artist and illustrator based in Kyoto. She is exploring the ancient capital through travel, collaborations with local businesses and publications, and just having fun. Catch more of her works or say hi on her Instagram @suzu.zz

Instagram link:

https://www.instagram.com/suzu.zz/