I saw my father’s ghost yesterday, I said, but the girl wasn’t listening. She didn’t seem to hear, even when I said my father wasn’t dead.

The black marbles in the whites of her eyes were following something behind me. He’s always been early, I said – for everything. “Better three hours too soon than a minute too late.” We blamed Shakespeare personally, my brother and I, I told her, for the hours spent waiting at train stations. She didn’t answer. I described the ghost, throwing words into the void. Said I’d seen it in the kitchen, that it was wearing a dhoti, and was eversoslightly jelly-like around the ‘edges.’ I told her that when it’d seen me it’d disappeared. Poof. Gone. I didn’t tell her what Ma had said, about the anti-anxiety drugs, the possible ‘hallucinations.’

The teahouse was dimly-lit. A teaspoon caught the light from the kitchen, and I thought of the train tracks flashing silver in the dark. The shining hose water of the railway cleaner on the line. The smell of frying chickpea batter and the tamarindy taste of jhaal muri wrapped in paper. How we’d played Eye Spy and Sambit would pick obscure things from his view that’d turn out to be something like ‘The Man With The Red Jumper On That Platform Over There.’ I thought about the people that appeared and disappeared like smoke at Howrah, as trains came and went. I didn’t think about my father, because all of those things – everything – had become a memory of him now, fragmented and infinite.

She was thin, the girl. (Or woman. She could have been twenty or forty, but anyway I wasn’t sure age had anything to do with being a woman. At the hospital I’m always a woman. A woman with lists and a good memory for medical terminology. Is your daughter a doctor, Mr. Sen?) She seemed to grow thinner the longer we spent together. Her neck appeared to be stretching, becoming threadlike, which made her ears look smaller, like delicate, white oysters.

Her eyes fixed on something as it landed on the next table. A plate of veg momos like tiny lungs. She licked her lips, folding them inwards, and looked back at me. Her mouth was the beak of a spring bird, tiny and made pointed by the full lips that jutted out. She covered it with her hand, her chin resting on her palm.

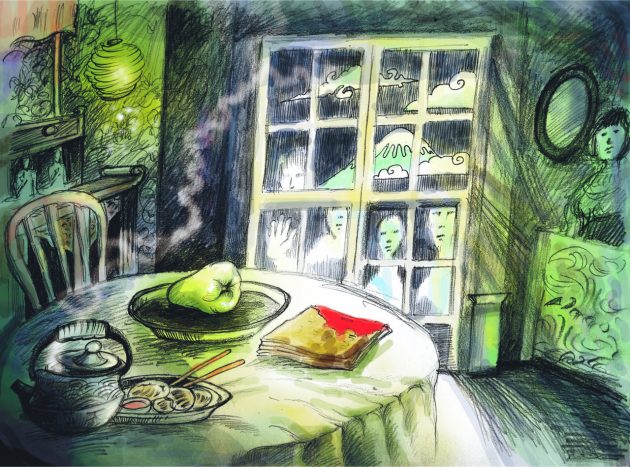

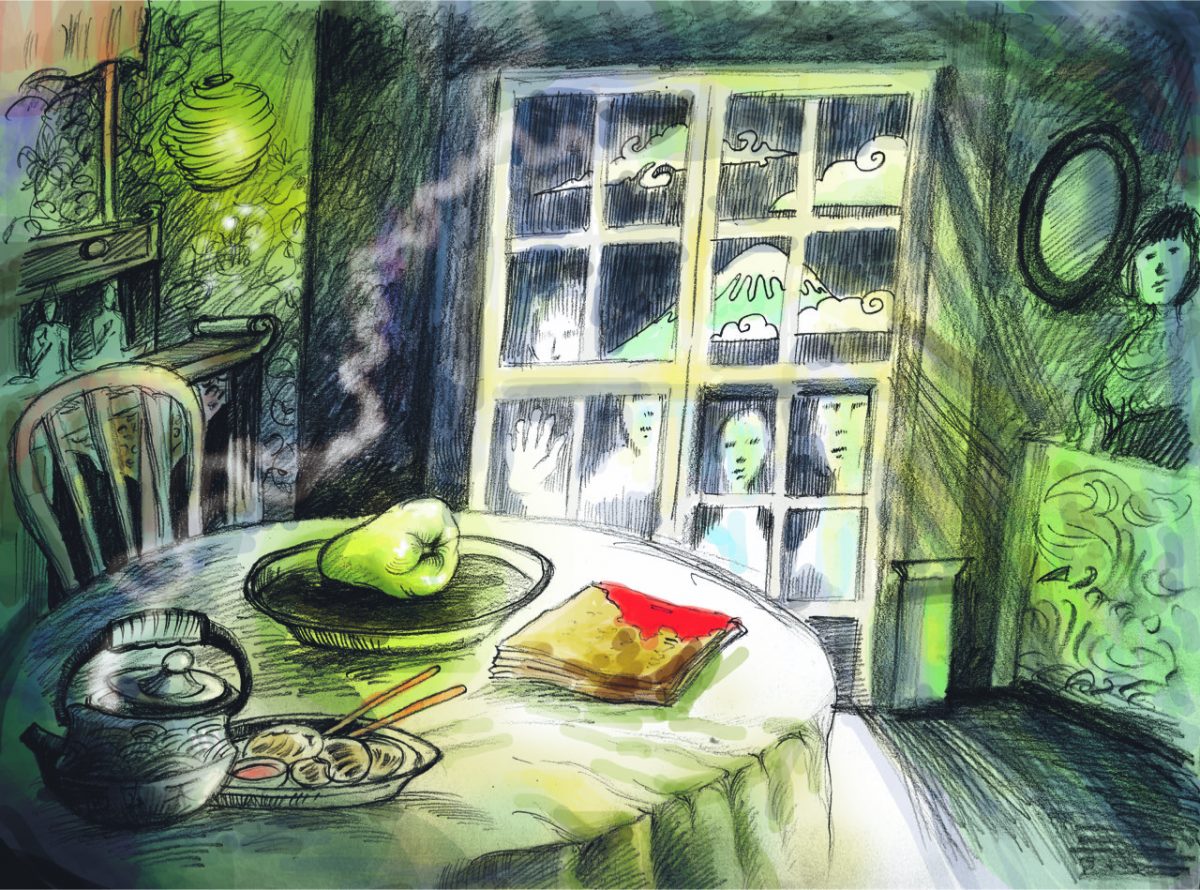

I wanted to talk to her more about Babaji even though we’d only met an hour before. Tell her how on different days he reminded me of different animals. A lamb, a lizard, an owl, gazing up at me, vulnerably unhuman, a spoon in his mouth with big translucent eyes, his head flowing with mucus in long, glittering strands. How I’d started to call him by his bhalo nam as if he being my father was already something that existed in the past. People you know want to be told it’s getting better, even when there’s no fucking hope in hell. Because they don’t know what to say. And we don’t want to make them uncomfortable, do we, so we tell them it’s alright, could be worse, taking each day as it comes. I wanted to tell her that as we inched closer, because it seemed we were all dying then, familiar things had begun to seem dead. Things that had never been alive in the first place. It was as if the house were filled with organic matter that’d been manifesting as everyday objects the whole time, and now they were decomposing: roots and husks and flesh and skins wrinkling, turning green, bursting and releasing sticky gases. But I sensed Li-Hua was more interested in the dead than the dying. In front of her was a copy of the The Overseas Chinese Commerce in India opened to the deaths section. She’d been looking, she said, for people she knew.

“Do you know it? The Blue Chrysanthemum, Sun Yat Sen Street? Doesn’t have many customers these days,” she said and waved a hand above her teacup and steam rose over her face making her gaseous and abstract. “There are ghosts there,” she said without changing her tone and she tapped her fingers, which were long, bendy and moon-white, on the table as if conjuring one up. She had long pointed nails, transparent, like sugar paper. “Old customers. One woman, Mrs. Fatt. Spent all her husband’s money buying clothes and jewellery. Always wore the same sapphire earrings. Now she’s inside one of the lamps in the hallway. A dark blue light that flicks on and off. Those are ‘weird ghosts,’” she said, pouring sugar from the pot into her cup instead of using the spoon, “yaogui, in Chinese. People who can’t stop spending money in life become yaogui.” She told me about animal ghosts and nightmare ghosts and ghosts with bad breath. Ones that become lights and wind and physical objects.

“Some can transform themselves into any person,” she said. “See the altars outside? It’s ghost month. People are feeding the ‘hungry ghosts.’”

“Souls of ancestors?”

“Demons,” she said, and she straightened her skirt and checked for the pearl earring in her oyster ear. “We have to feed them.”

I looked towards the windows but not out of them because they were heavy with condensation from the steam. It was a monsoon night on the fringes of Tiretta Bazar. Rickshaws, taxis and buses moved like amphibians through riverine roads, shining white lights into black water. I remembered that ‘everyday 12,617 passenger trains pass through Indian Railways and the trains are never empty.’ Never empty. A drop of rain on the window separated from its string of watery pearls and dropped. We never talked about it at home, that he was dying. It was when you went to bed that the memories clawed over you like rakes on earth, and you cried, mouth open, making no sound, and that was how you went to sleep, in the end, with the wet face and the aching jaw like a horrible Edvard Munch painting. And no auntie or uncle ever says ‘how are you?’ because it’s not about you, is it. Out of the window I imagined a moon lighting up mountains that looked like they’d been cut out of paper, only half-real in a gauzy landscape filled with mist and birds hovering over dragon rivers. In the daytime the mountains would be emerald green with white houses with ruby roofs folded into them, sky golden under a red sun. The once plentiful Chinese community in Kolkata had begun evaporating like water from stock. Chineseness was a colour now that flashed red, in peeling paint, latticework, signage on church walls, and the crumbling bricks of heritage buildings sinking into the ground.

The magazine lay on the table between us, by Li-Hua’s teacup. I hadn’t yet seen her take a sip. It’d stood out because of the rose apple. It might’ve been a pear, with a stubby, waxy body in ice-green but it looked like a jamrool, which was my father’s favourite fruit. He’d paid a small fortune for jamrools that came to the city from rural Bengal. Beside the drawing were characters in Chinese, in a slim font where the vertical line of the last symbol flicked out and up like a cat’s tail. The cover of the magazine was in a disappearing colour that’d once belonged to ‘red’. Centred at the top of the page were the hand-drawn words in English: Short Stories. It must’ve been because all the other magazines were in Bengali that I was attracted to it at The Little Magazine Library on College Street that I’d gone back to, to leaf through the old publications a year after graduating from UB. Back then I didn’t know happiness was a thing I already had and didn’t need to search for. When I went again I tried to recreate that time, holding the fading jackets, gritty in my fingers. Now I fixated on them as objects I could pick up that seemed to make time physical. They were older than my father, painted when he hadn’t even become an embryo, and I thought as I left and it started to rain and I walked aimlessly noticing how the paan stains on walls looked like blood bursting from the earth, that in a way they mocked him, didn’t they, the magazines, because he’d existed for less time — he’d been blip in the world of, even fragile, objects.

“I don’t speak Chinese,” she said, although she’d been looking inquisitively at the magazine through the transparent plastic bag. “But that says ‘Pear-Blossom,’ and she pointed to the title. The magazine had drawn me to Chinatown despite the weather, or maybe because of it, and despite the distance from my house in Ballygunge.

“I don’t speak Chinese,” she said again, “but I can read my name,” and she smiled showing straight, square teeth. “I can read basic things. Street signs, menus. Not literature. I can read Tagore but not,” and then she said a Chinese name I didn’t know. “My grandmother speaks Mandarin. My grandfather spoke Hakka, but he’s dead.”

She’d been sitting in a dark corner by the hatch to the kitchen, where bamboo steamers were piled high like the warped trunks of trees on stainless steel. I remember her long hair like a lacquered museum object being the antithesis of my own. Unaffected by the vapour in the air, by the monsoon, as if she were timeless. And she was thin, and I wondered how anyone could be so thin, their bones like decorative structures under the skin. Her face was beautiful but with hollows in the cheeks. She wore a yellow skirt in sunshine pleats, which fell below the knee, hanging low on her sharp hips, and a matching shirt with short, ruched sleeves that looked like little lettuces, from which her dainty arms extended.

Li-Hua said she didn’t know anyone who could help me translate the stories when I asked her. Her family had either died or gone back to China.

She opened and closed the metal lid of the white teapot, as if the clicking sound gave her pleasure, and turned to look back at the food. I asked her if she wanted to order something.

“No.”

“Aren’t you hungry?”

“I’m on a diet.”

It wasn’t her fault the doctors had put a tube in my father’s stomach, that he would never eat again, but the idea she chose not to eat seemed unkind, as if it were for my benefit. She turned from the other table back to me as the last morsel of dumpling disappeared. We’d spoken of two things since we’d sat down together in the teahouse: ghosts and food. Impermanent things. Li-Hua talked about real Chinese food, not the ‘Chinese food’ we have here, and when she said that she made her bendy fingers into rabbits’ ears, squish-squish. Snow vegetables and chrysanthemum leaves, lily bulbs, osmanthus blossom and immortal radishes, pine trees, foraged foods, drunken dishes, and ‘meatballs like lions’ heads’. Ingredients that came from ponds and lakes and rivers and mudflats in landscapes neither I nor Li-Hua had ever seen. When Li-Hua talked about food she used a different tone to the one she used when she talked about ghosts, which was blasé, itself lifeless. Instead her eyes flashed and looked out, past me, as if into another time and space. But I never saw her eat a thing, and she left her cup of tea untouched as she stood up to leave.

“Do you want to make dumplings, at the restaurant?” she said. I did. I was scared of going home. Better to be away, better to ignore it, not to see it, even though I’d become numb to a lot of it now. “Be careful,” she said, “of the ghosts” as we walked into the electric Bowbazar night air, dusty with camphor. “If someone calls your name don’t turn around… The gates of hell have opened.” I checked for a glint of a smile as I caught up with her but there wasn’t one. The blackness flickered with the lights of candles on alters lighting up the waxy skins of fruits left out by congregations. The air was sticky like chutney, and it locked little papers into it that hands threw up from the ground. A giant green-faced dragon of paper, tinsel and fire passed down a street to our left flashing gold. When we arrived at Sun Yat Sen Street the restaurant was boarded up. It looked as if it hadn’t had a customer for years. But when we went in through a rear door the kitchen was alive. The pulp and roots of vegetables lit up in red and blue under the neon light. They sat hard beside the softness of steamed lotus buns that seemed to be wholly female: magical woman-creatures that reminded me of animated films, floating in mossy forests without faces. The room smelt like gelatin sweets, and fish as fresh as water. Duck eggs on the counter had been cut into neat wedges, leaving them to show off their glowing middles, and a long half-gutted fish lay on the dark counter with lacy skin and sequin scales shining, as if it had been murdered on its way to a party. Beside it were the remnants of braised pork, some whole star anise sprinkled around a mooncake like tiny pieces of wooden furniture next to parcels of vermicelli, and cabbage layered in sheets, belonging to a princess’s bed. Through a half-open door was an empty dining area with white chairs, a line of ceiling fans and peeling floral wallpaper.

Li-Hua hung off of the kitchen counter, languid, and for the first time I saw that her stomach bulged out. It was round and hard-looking, as if stuck onto a wire frame. She’d said nothing about being married or about a boyfriend, and anyway I wasn’t sure it was a pregnancy. It looked more like malnutrition, as if she were literally starving.

She gave me the flour and yeast and pointed to the sugar for me to mix in a bowl. I followed her instruction, making a well in the middle and pouring lukewarm water into it, to make a soft dough. She watched me add baking powder. No, a little more, she said. Then the lard went in. I kneaded the dough and she seemed pleased, and handed me a damp cloth to lay over the bowl.

She told me we wouldn’t eat any of the dumplings. That, it was bad luck to eat food left out for hungry ghosts. It would make them angry. I remembered reading about hungry ghosts, wasted, mouths too small to eat. They tried to possess people, sometimes the emotionally weak, so as to be able to taste the food they craved. I thought about my father, who’d be sitting now in his special chair of man-made fibres from hospitals, and the cushion made of chemicals. I breathed in the perfume of spring onions and the smoked tea that Li-Hua had poured out but again hadn’t drunk any of. He’d be smiling, my father, as he always did, because he was still alive, taking the pain and loss of dignity in his stride as he had taken the bankruptcy, the loss of the big house in Jodhpur Park with its vines and balconies and lawns, and the humiliation.

Leave it, now, she said, and sat on a chair by the wall, and bit her lip on her little mouth.

“My father’s dying,” I said, and it was loud, as if I’d knocked a frying pan onto the floor.

“How do you feel?” she said, biting a nail, with a flat expression and the left side of her face in shadow. “Knead the dough again”, she said, as I started to speak.

I told her I saw his name everywhere, where I’d never noticed it before, and that smells and words reminded me of him, and that ordinary objects of his had taken on an unordinary significance, as if suddenly they contained all of the meaning in the world. “I understand,” she said. Li-Hua had lost everyone. I wondered why she’d been left alone, why she had no one at all. I brushed the layers of the bamboo steamer with lard.

“Cut 14 squares of parchment”, she said, knife-like. I cut off pieces of the dough to make discs. I rolled the discs into circles that were thinner around the edges, and took one, as she told me to, in my left hand. From a box of aromatic stuffing I placed a teaspoon and pressed into the centre. We’d stopped talking now, the girl or woman and I. Li-Hua had become almost invisible in the corner of the room as it grew darker, the street lights waning outside.

I pleated the edges, like she told me to, sealed the buns and put them on top of the parchment squares. I remembered being four years old as I filled the steamer’s layers with squishy dumplings: red plastic shoes with a buckle, an Alice band, red Plasticine on my hands. People died when they were old, didn’t they? When their hair was white. When they were like Dadaji. Not now, not yet. I’m not ready. And then the fear filled me up, the insatiable fear. He was the only one who really loved me. But it was huge then, because it wasn’t just that. He was everything, the blood and the oxygen, and the need to scream built up in my stomach like hunger.

When I looked at her across the room, she seemed to be even thinner still, her stomach more bloated. In the dark she looked like a waft of smoke, curled and stretching upwards. One of her hands was lit up on the counter, and her nails looked black. The buns smelt sweet now. The smell reminded me of something intangible, something else, from a time in the past. I saw my grandmother’s garden of roses and my father in his shorts, and for a split second I was there, a child with the taste of lemon sherbet on my lips. Then at school, on the first day in the giant entrance, my father driving away, and the smell of something I’d forgotten, of food cooking that was sharp-smelling, not like food at home. I didn’t feel any more capable now than then of navigating the world alone.

When I looked up, where Li-Hua had stood was my father, smoking a cigar, resting on the counter in a biscuit-coloured suit, the trousers drawn around up as his legs crossed at the ankles, exposing socks in the same shade. His hair was slicked back and he was smiling.

“Are you okay?” said Li-Hua who appeared in his place now, and hot tears gathered in the corners of my eyes that had begun to sting. I looked at Li-Hua with her moon-white flesh and her hair that stayed still, and her frame thin like a daddy long legs. I thought how different we were and yet how we were both from disappearing worlds. She came over to the oven, and draped an arm over my shoulder. I shivered as she did, and threw it off by accident or instinct, but she put it back, tighter this time, strangely cold in the humidity, and I pictured a snake in the dark. I could feel droplets of sweat gathering at my hairline, my mouth going dry. I felt her breath on my face which smelt like fermented fruit, and the whites of her eyes glowed like eggs. She smiled at me, tilting her bony skull. The stainless steel under my hand felt like ice. The kitchen suddenly smelt rancid or like food clogged in the drain, and the damp air had gone cold.

“Sorry,” I said, “I have to go home,” and as I escaped to the bus stop through homages to the dead on altars and steps, lotus-shaped lanterns flying overhead, I wasn’t sure if I was running from her, or to him. As I turned to look back, Li-Hua who I’d thought at first was following me, chasing me, and I’d had to catch my breath, lay down a plate of dumplings outside the Blue Chrysanthemum, and sat on a step. At the bottom of the road I passed a fruit vendor selling the waning season’s jamrools by parked taxis and police cars, and I bought five, paying double what I should’ve. The bus coursed past South Park Street Cemetery with its gothic moss-covered tombs. I turned the pages of the magazine, leafing through indecipherable script, and felt empty. When I got home the house felt different. Less like it was rotting away. Babaji wasn’t there. They must’ve been getting him ready for bed. I felt ashamed that I’d become so consumed by death when there was still time to give something to the living. I sat up cutting jamrools for him, slicing them thinly.

“He can’t eat those,” said my mother in a tired breath. I’d forgotten he couldn’t, of course he couldn’t, he couldn’t swallow them, hadn’t been able to for months. I knew that. And then the room shifted, as if the house had been picked up and dropped back down again and I remembered. My widowed mother looked at me, begging me. She put a slice of a jamrool in my mouth. It melted, sour, on my tongue. I ate the whole fruit, another and another. I ate and I ate. Buttery breads and daal and pickles and sweets, syrupy malpoa, and the pomfret and the charchari when they came, one and a half red-velvet cakes and yoghurt and mango and jackfruit, and popcorn, but nothing could satisfy it, this new hunger, this new, great hunger. Every food was a memory that became biological and foreign when I swallowed it. And so like Li-Hua I stopped eating, and left out a jamrool for the ghost.

Georgie Carroll is an author and a PhD candidate at SOAS, University of London, and based between the UK and India. Her piece published by Asia Literary Review, The Messenger, was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She is the author of “Mouse”, part of Reaktion Books’ Animals series.

Arghya Manna is a journalist, an illustrator, comics artist and PhD dropout from India. He is an enthusiast in History of Science. Through his blog www.drawinghistoryofscience.wordpress.com, Arghya loves to explore the stories of science and history. He believes in storytelling through comics.