The Japanese garden is in a perilous situation. Its native habitat is being destroyed at an alarming rate to make room for tall, modern, more profitable buildings. At best, these buildings may have a forlorn scrap of a garden shoehorned into a corner in front. Even where there is space ot be had there is some question whether the Japanese garden can keep pace with society and still have meaning and purpose in the years to come. Overseas, certainly the Japanese garden languishes as a “cultural artifact” or a “museum piece,” sharing no cohesive tradition to give it a sense of belonging. Yet, among the myriad gardens to be found in Japan, one type might easily bridge the culture/time gap and thrive in the future. Just like the treasure of The Tongue-Cut Sparrow, this precious thing is to be found in the tiniest package; in this case the tsubo niwa (courtyard garden).

The word tsubo itself is very interesting (niwa simply means garden) and gives a clear insight into the meaning of the garden and its potential. One meaning of tsubo (written 坪) is: an area equal to two tatami mats or about 3.3 square meters. Most tsubo gardens are small, some only a few square meters, many larger, but the implication of this definition is that the tsubo garden is ‘very, very small.” So one way to think about the tsubo garden is in terms of its size.

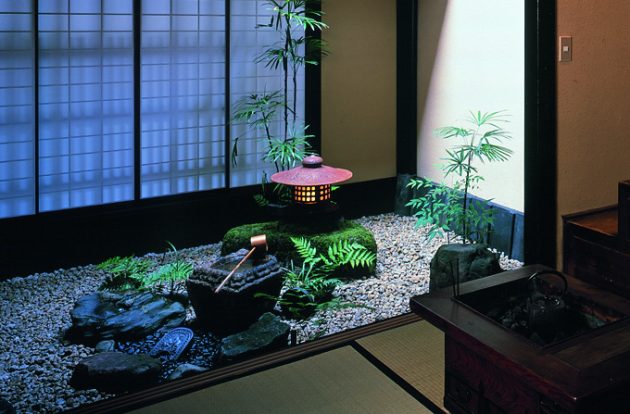

A second meaning of tsubo (written: 壷) brings a new dimension to the garden. In this case tsubo means a vessel, usually ceramic, such as a large water jug. Now we see the tsubo garden to be not just a tiny garden, but a three-dimensional space, a volume that is held between the walls of surrounding rooms, with an earthen floor and a lip made of wooden eaves. Within this vessel is the garden; soft light, rain pattering on leaves, the sweet smell of a gardenia. So in this case the tsubo garden is contained inside a building, like a jewel in a box.

Both of the above mentioned kanji are commonly used. Architects tend to use the character with the first meaning on their plans, while that with the second meaning appears more in books about gardens. There is a third way to write tsubo (経穴) that brings the garden out of a purely physical definition and in the realm of, dare I say, the spiritual. This way of writing tsubo has never been used in connection with a garden before (to my knowledge) which surprises me; it seems the most fitting.

There is a belief, in most countries influenced by Chinese culture, in ki or “life energy,” a force that flows through all things. Its movement through the body has been chartered for centuries; along its lines of flow there are special points, something like the pressure points of the nervous system. These points can be manipulated by finger pressure (shiatsu 指圧), inserting fine needles (hari 針) or even burning medicinal incense cones on the skin (okyu お灸) in order to invigorate the flow of ki. In Japanese these points are called, you guessed it, tsubo.

A building in its entirety is much like the body; life flows through it over tie. Even as the manipulation of the ki, tsubo can invigorate the body and spirit. The tsubo garden, in its own quiet way, can have a powerful effect on the people who live with it. It is a tiny point of calm and beauty around which swirl the events of daily life; a well-spring of quiet harmony. What architecture, what culture of society wouldn’t benefit from that? This is the beauty and power of the tsubo niwa.

Perhaps you’ve seen them in old shops or temples in Kyoto. Surrounded by various rooms that have been extended from time to time to meet the growing needs of the residents, there may be a tiny “leftover” space. The garden built in it is a lesson in reserve; in one that I’ve seen, just four or five stems of bamboo rose almost vertically with tufts of leaves clustered at the tops. A large stone lantern basked in the light that poured in from above, while at its foot a cherub-faced carving smiled wisely up at those who entered. The garden was just as simple as that, and immaculately kept. The salt and pepper gravel on the ground was completely free of weeds and the veranda had a soft sheen from years of daily washing, lending the whole a sense of loving care.

The light that filled the garden shone through the shoji of the surrounding rooms. Slide the doors open and look and the vertical lines of the bamboo and lantern guide your eye down to the round face fellow and his warm smile, drawing you in. If you sit and look for a minute it soon turns into an hour as one thought leads to another and dreams hold sway over time. A more complex garden would tantalize the mind; this one just quiets the heart. That is the magic of the tsubo niwa.

Tsubo niwa do not need to be made of bamboo and stone lanterns. These are of course part and parcel of traditional Japanese design, but there are fundamental elements that need to be understood so as to avoid superficial mimicry. One that has been mentioned already is simplicity. It is very easy to overdo these gardens, to try to have them flower in all seasons or create complex scenes, with rocks and plants. The calming effect is all the more powerful with a simple arrangement.

A second point is their size: tiny. This put the garden on a human scale which is accessible and manageable; more along the lines of sculpture than what is usually thought of as a garden. On a less philosophical plane this smallness is economical, requiring little space and costing little to build.

A third point would be that they are entirely enclosed by rooms or garden walls. This lends a sense of immediacy. Tsubo niwa are not places “out there” that one goes to stroll in, they are integrally connected with the architecture and life going on inside. Because of this they tend to become a part of one’s daily life. Always present — throughout the day, throughout the year — they play a different, more intimate role than large, more sumptuous gardens meant for social events.

These three points, plus the central theme of natural rhythms — tsubo niwa are essentially abstracted fragments of Nature — are the basic constituents of the garden. One last important point does not concern the form of the garden, but rather its care. Most tsubo niwa wouldn’t take 15 minutes a day to sweep and water, but in that short time you become connected to the garden. You might say the ki you put in is the ki you get back. The daily care of the garden is made easier by all the basic elements o the garden’s design: simplicity, smallness and proximity. Through this ritual cleaning, the calm of the garden becomes the calm of your heart, and the calm of your heart shows in the garden for all to see. To have a tsubo niwa and leave the care to someone else would be to rob yourself of the best part.

So where will the tsubo niwa be in 50 years? In homes and stores, certainly, libraries and think-tanks perhaps. Why not an office tower, one of the “intelligent” buildings that purports to hold so much for the future, peppered with tsubo niwa from its subterranean toes to the brow of its observation deck? And the people within all the better off for it.

Marc Peter Keane is a garden designer, artist, and author. Having lived in Kyoto, Japan, for nearly 20 years, his work is deeply influenced by the aesthetics and culture of Japan. His most recent book, Japanese Garden Notes, is a collection of design ideas gleaned from over 100 gardens. www.mpkeane.com

Photos by Marc Peter Keane, taken from the book: Japanese Garden Notes: A Visual Guide to Elements and Design” (Stone Bridge Press, 2017).