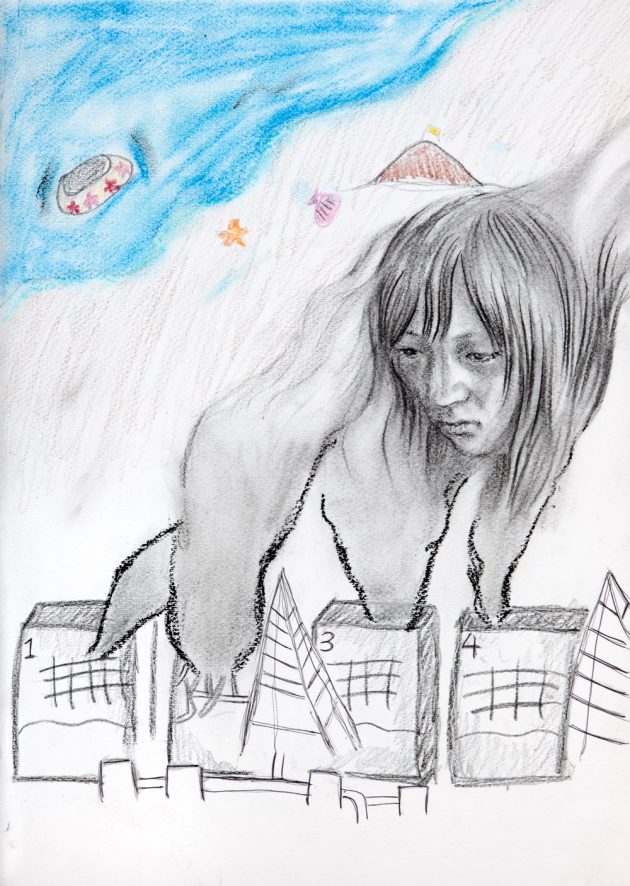

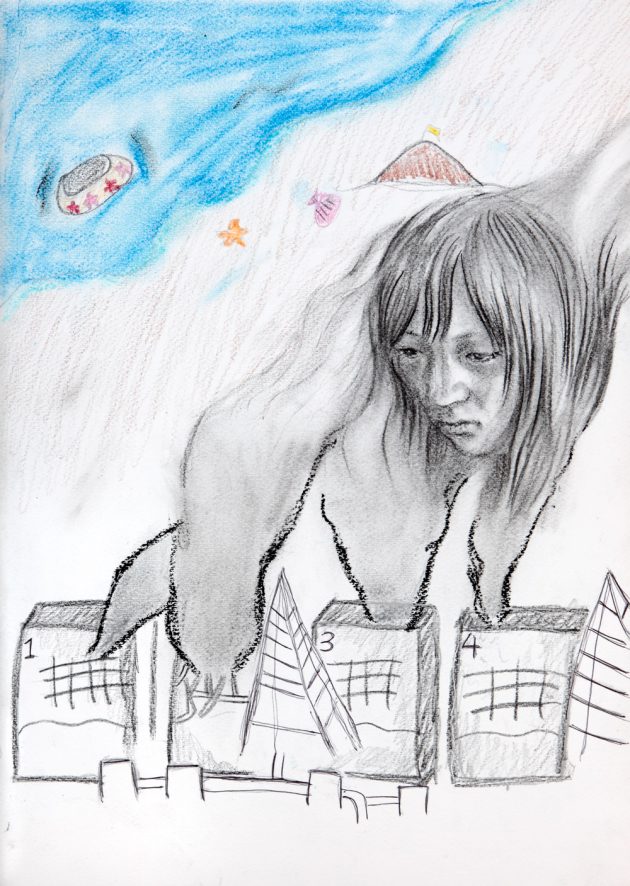

Collaborative pictures with portraits by British artist Geoff Read, who was living in Fukushima with his eight-year-old son at the time of the Tohoku earthquake, tsunami and nuclear crisis of March 11, 2011.

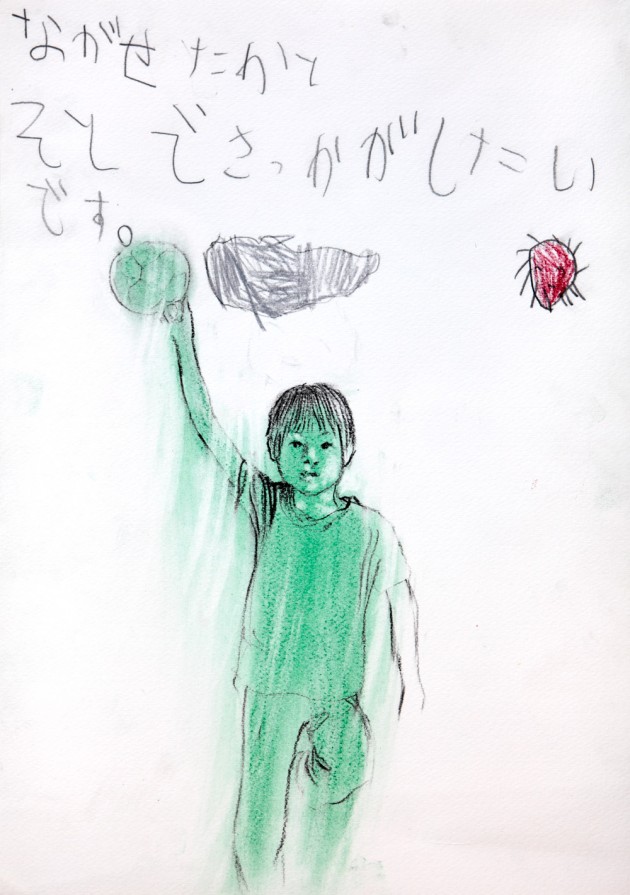

THE SMALL BOY from Fukushima City sat by himself for a long time, staring at the blank sheet of paper in front of him. Around him, children were getting on with drawing their rough ideas— choosing colours, poses and positions for their portraits to be added later. But this boy was silent. He began to look worried as the minutes dragged past, and I imagined the white of the paper spreading out in his mind like an impassable glacier fraught with crevasses: “What is required of me? What is the right answer?”

My collaborative artwork with children is based on the principle that they are strongest and most resilient when they are listened to, respected, and encouraged to think creatively. Children often need a suitable environment in which they can develop their own ideas about their situation, to make sense of their emotions and express their thoughts. These can include feelings that adults find difficult to acknowledge in children, like fear, sadness, grief, frustration and anger — as well as the more socially permissible, innocent and joyful side of childhood often expected of, or even insisted upon them.

This is especially true in Fukushima with the triple trauma of earthquake, tsunami and the ongoing nuclear disaster threatening children’s long-term health and mental well-being. The twin pillars of childhood in Japan are cuteness — kawaii! — and the spirit to struggle on — gambare! Innocence and determination are protective in many ways, but they can also be limiting, making it difficult for children to express their uncertainty.

The other children showed me their ideas, then got started. But this boy, his forehead knotted with tension, said he couldn’t think of anything. What should he do? No rush, I said, he could take his time. There was no right answer: anything he did would be good — even nothing. How about starting with my drawing of him, then maybe he could add to that? Mmmm, OK. What pose would he like to use? Just sitting. What colours would he like to be? He chose.

As you can see from their pictures, the children I met in Fukushima want what any child wants — to kick a football, to play outside with their friends, to engage with nature and eat an ice cream without worrying whether it is contaminated. For many, this is no longer possible. In Fukushima’s countryside, children traditionally had an intimate, hands-on relationship with the natural world, collecting giant stag beetles, handling big dragonflies, picking wild mushrooms and vegetables in the forest with their grandparents, or helping in the fields. The food they ate was of very high quality, often plucked straight from the allotment and served on the dinner table. Now, by contrast, many parents are struggling to find food and drink from safer areas for their children, keeping them inside, the windows closed. Childhood as it was known before is over.

I have a few more questions before I start. What size should he be? Small, of course. Kicking his legs against the stool, he otherwise sat quiet and unsmiling, looking around him and gazing out of the window. He would only meet my eyes when I asked him to — he had decided that he should be looking at the viewer. He seemed to be in a world of his own, and I was glad he felt no need to perform a camera smile.

Parents’ worries about radiation are rational. Scientific knowledge and consensus about the risks and biological mechanisms of long-term exposure to relatively low levels is still lacking. The uncertainty is unsettling, and parents often told me they felt badly let down, deceived and endangered by vested officialdom. In the absence of independent media they have had to resort to the internet, especially Twitter and Facebook, in order to find and share reliable information. They are waiting for guidance and support that may never come, torn between taking up offers of help from elsewhere in Japan and keeping the family together. They are frustrated by the difficulty in sourcing food from lower radiation areas. Especial anger is reserved for wrong-headed attempts to equate supporting Fukushima with keeping children there and with eating its produce — including in school meals.

Children absorb some of this worry and anger, but know very well what they can and can’t say about it. Our need for them to be happy is so strong that in effect they try to protect us, and try to endure. Yet evidence from the world’s disasters suggests that internalising painful experiences is damaging for children.

He returned to the table with his picture. After a while he took a box of watercolours and tentatively began mixing some blue paint. Within a very short time he had finished. The boy had painted a blue patch at the bottom. No, it didn’t need anything else. I made the crass mistake of asking him what it was — and he burst into tears. I found him and gave him some nice paper and a pencil, telling him he was a good artist and many people would see his idea.

Of course, what Fukushima’s children really need is as little exposure to radiation as possible. For many, evacuation is the only practical way to achieve it, but that has become a highly politicised subject. I want to create a channel for children to contribute to that debate, and to affect the policies that shape and limit their living conditions, health and happiness. Of course, practically speaking, children are fairly powerless, but it is important now more than ever that they are listened to. They need an alternative to passively receiving information and instructions so they can grow into active citizens and learn how to keep themselves safe. Talking and making links with others in the wider world through their images and words encourages them to be pro-active. This completes a positive circle they can feel proud of and empowered by — and by looking at their work today you are helping to contribute to that process.

In the meantime, the amazing resilience, social cohesion and good humour of Fukushima’s children will help them. In difficult circumstances such social capital is a firm foundation, but this strength should not be used as an excuse to ask too much of them. The eyes of the world are on Fukushima, but the eyes of the children are gazing back, demanding a response.

My annoying slowness ensured that it took me a little while to understand what Hiyato, this young boy, had made. Its potent simplicity, direct and ambivalent at the same time, somehow allows us space to feel ourselves as children again. Hiyato had battled with his own sense of powerlessness and seeming inadequacy, yet had create an image out of a thought unlike anyone else’s, and moreover dared to do so in a group setting. Initiative, individuality, and creativity: this is what Japan needs.

More images from the project at http://strongchildrenjapan.blogspot.com/

A useful annotated bibliography of resources on the impact of disasters on children is available at the National Children’s Advocacy Center.