[T]hirteen years ago, Yumiko Mori and Toshi Takasaki, both visiting scientists at MIT’s Media Lab, had to delay their return to Japan by a few days to attend another meeting in the U.S. Yumi cancelled their flight reservations from Newark to San Francisco. The flight she cancelled was United Airlines Flight 93, and the date they had been scheduled to fly was September 11, 2001. This change of plan not only saved their lives, but prompted them to rethink and change their professional paths.

In the days following 9-11 Yumi heard many remarks revealing prejudice and hatred, including how “scary” and “dangerous” Muslims and Arabs were — remarks based on ignorance and bias. A friend told her she must have survived because she had some important things to do. Witnessing the growing xenophobia and nationalism in the U.S., she asked herself:

“Would we be able to decrease the incidence of dangerous generalizations, based solely on one’s background, if there were a place where children around the world could meet and get to know each other? How could we make that possible?”

Thus, in 2003, Pangaea (www.pangaean.org) was founded — a non-profit organization that creates a “universal playground” where children from around the world can develop personal bonds beyond the barriers of languages, geographical distance, and differences in social backgrounds — a world made of a single piece of land, one continent, without borders, just as the world was so many millions of years ago.

Thinking about funding this work, Yumi asked, “What if just a tiny percentage of the money put into defense and military was directed toward more peace-promoting projects?”

[I]n 2002, my US-based NPO, Viewpoints Research, had been invited by Kyoto University and some Kyoto city schools to work with teachers and children to introduce them to “Squeak” — a free and open-source software program we had created to build models and simulations. A mutual colleague at MIT’s Media Lab introduced me to Yumi and Toshi, who were at that time involved with the Children’s Art Museum Project (CAMP). Together we held workshops at CAMP where children, parents, and teachers collaborated to create “Etoys” using Squeak.

After Pangaea was established, we continued to investigate how to create fun learning environments (some over long distances) where adults and children could learn and play together, and use IT to help bring children from around the world together to explore cultures other than their own. It was clear that our organizations would enjoy a long-lasting relationship.

Yumi and Toshi decided to start their organization in Japan because they saw a need for a “go-between” to connect children from different cultures, religions and countries.

“Why we felt this so strongly may have a lot to do with the fact that we very naturally accept and respect people with differences. Japanese people at times are referred to as those who cannot say ‘no’. But there is some good quality in this. We value listening to others and trying to resolve conflicts through peaceful discussion. This is an important and admirable value. Therefore, we felt that Japan was the right place to establish our organization and develop it with people who shared our vision.”

Today Pangaea has sites in Japan (Tokyo, Chiba, Kyoto, Mie), Korea (Seoul), Malaysia (Kuching, Bario), Austria (Wien), Kenya (Nairobi), and Cambodia (Phnom Penh). More than 6,000 children, from 3rd through 9th grade, have participated in over 500 Pangaea activities. A primary Pangaea event is a free daylong workshop, usually held on a Saturday or Sunday with children aged 9-15. More than 350 registered volunteers support these activities around the world.

Utilizing information technology and communication resources created “in-house” and by collaborators, Pangaea has developed collaborative activities for children as well as software and other tools to support these activities.

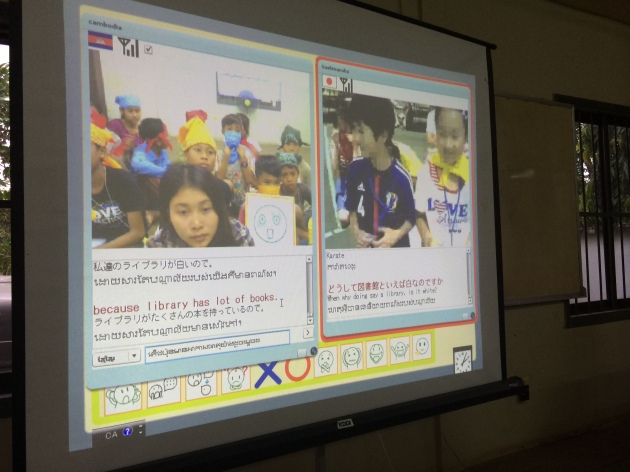

Kyoto University, especially the Ishida & Matsubara Laboratory at the Department of Social Informatics, has become a strong supporter, offering Pangaea the use of their facilities for the Kyoto workshops. Thanks to their high speed phone and data links Pangaea can hold a single workshop attended in real time in two or more countries, enabling children from Kyoto and Seoul, Korea, for example, to spend a day together engaging in collaborative play.

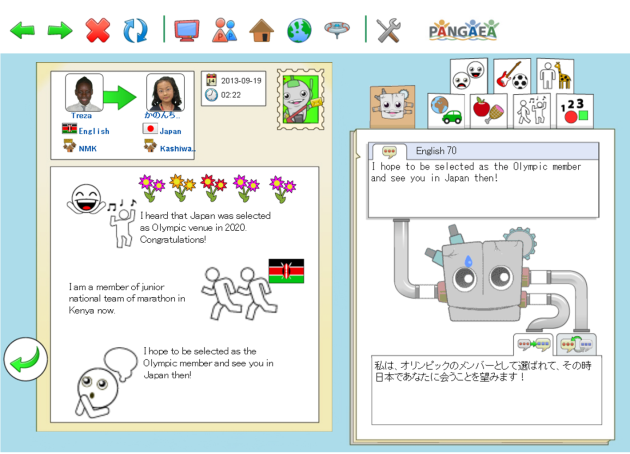

[T]oshi realized that language differences between the children could hamper communication, so he developed software to provide a communications bridge. He created PangaeaNet, a safe platform for messaging, offering over 500 “pictons” or pictograms the children use to communicate via email to learn about one another. A soccer ball and a smiling face or heart might be combined to ask “Do you like sports?” A piano and smiling face might indicate the child plays the piano. The pictons help the children express their emotions in ways that may be difficult for them to articulate in words.

Webcam activities are designed to offer real-time interaction among children from different locations by connecting multiple activity sites making places that are far away seem like they are next door. Children who may already know each other (through earlier picton-based mail sent through PangaeaNet) can further deepen bonds by experiencing face-to-face personal communication and playing original games via web cameras. The children also engage in project building and sharing examples of their culture’s traditional song and dance during each workshop.

The “Language Grid” also helps Pangaea connect people of different languages. Initially developed by the National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT) and run by the Department of Social Informatics at Kyoto University for its non-profit users, the “grid” is a free and open-source network of 142 public and private sector automatic translation software and online dictionaries from 17 countries. Children can exchange short messages in their native language, which are then automatically translated on their computer screens in seconds.

Yumi and Toshi describe these development efforts as “Peace Engineering.” When Toshi and other computer software and hardware engineers come together to develop programs for Pangaea it is rewarding for them to know that their efforts are directed towards promoting peace, and not the kind of defense or military efforts that today’s engineering projects are so often connected with.

Faraway countries are abstract for all of us, especially children. Their knowledge of other countries is mostly drawn from what they have heard from family and friends. Once they have direct experience with similar-age kids in another country the abstract can become more concrete. Shortly after a boy in Kyoto attended a Pangaea workshop he heard a news report about an earthquake in Kenya. The next day he asked his school principal if the people in Kenya were safe and if there was anything he might do to help. He explained that he was concerned because he had made friends with kids from Kenya by participating in a workshop. Kenya had become more real to him through his Pangaea experience.

[P]angaea organizers and volunteers have seen kids begin to understand that children from other countries are more like them than they at first may have realized. Pangaea activities can even help to erase biases inherited by the children from their parents or grandparents.

Participants take pre-and-post-workshop surveys on their experiences. Before one workshop, Korean children were asked to respond to this statement, “I strongly like Japan.” Only 27% of the children agreed. After the workshop one of the children who had indicated they did not like Japan wrote, “Japanese children are good. I would like to play with them again.” The rate of Korean children who answered positively after the workshop rose to 62%.

After her daughter returned home from that workshop, a Japanese “Pangaea mother” relayed her experience:

“They were able to become friends in a much better way than they had initially expected and were able to become good friends with children from Korea. After speaking with my daughter, I deliberately asked her the nasty question: ‘TV and newspapers say that Japan and Korea are not in good relationship. How were the children from Korea you actually met?’ My daughter’s response was ‘That’s adults talking, right? Only adults say that they “hate” Korea, but that’s not us. We became good friends. They were all very nice.’”

[I]n 2013 Pangaea celebrated ten years of program activities. In summer 2014 a new program was launched, called KISSY: Kyoto Intercultural Summer School for Youths. Spread over six days, twenty-three children from Japan, Korea, Cambodia and Kenya participated physically in this summer camp-like program, another example of Pangaea’s efforts toward Peace Engineering.

The KISSY program was announced through local Pangaea activity sites and via the Internet. National Pangaea activity leaders selected children from Cambodia and Kenya. Pangaea asked that priority be given in the selection process to those whose parents or family members had never traveled overseas, and who were also eager to participate in the program.

The day programs took place at Kyoto University, a key sponsor. The kids stayed in a Kyoto Youth Hostel and kids from different countries shared rooms. Twenty-three children attended, so a slogan for the week was “Make 22 Friends!”

Mecell Okalo, a participant from Kibera, in Nairobi, commented on her KISSY experience:

“In Japan I made 22 friends including the staff members. I loved the place soo much in that we were all treated equally with no discrimination, all the people were appreciate and always had respect for each other. …Truly I love Japan with passion. I love them for their decency and I think they are role models too. I return my gratitude to Yumi and Mr. Mitei for their support.”

The first KISSY program was so successful that the next one is already being planned, for July 31 to August 7, 2015.

Pangaea has successfully brought children together to learn about each other, teach respect for cultural differences, and break down barriers that stem from prejudice and ignorance. People working toward common goals with similar beliefs tend to find one another — this is how Viewpoints Research and Pangaea were brought together. At the heart of both our organizations lies the idea that education can lead to understanding that humans are more alike than they are different. We can come to understand cultural differences and celebrate them, rather than fear them.

“If I have wings, I want to fly and visit Japan right now.”

— A 12 year old girl from Nairobi, Kenya after participating in a Pangaea webcam activity

Pangaea is seeking volunteers, new members, and sponsors for the next KISSY week.

Find out more at www.pangaean.org or contact info@pangaean.org

Kimberly Rose is co-founder and Executive Director of the NPO Viewpoints Research Institute, a volunteer supporter of Pangaea, and a proud resident of Kyoto. www.vpri.org