By Magda Rittenhouse

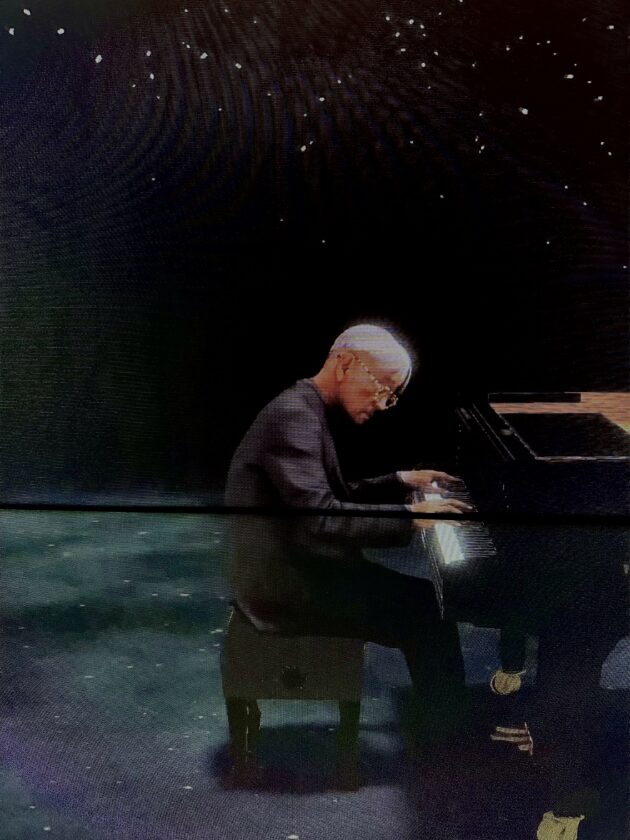

Wearing a black suit and tortoiseshell glasses, he leans over a grand piano. Spotlit, his neatly cropped silver hair shines in the distance. Coming closer, I can see freckles on his pale face. He lifts his hands, lets them fall on the glossy keys, and begins ‘Before Long,’ the first of ten solo pieces he will play tonight. I can see the hammers of the Yamaha twitch.

How is this possible? The piano was not in the theater minutes earlier. And the musician—Ryuichi Sakamoto—passed away in March of 2023. Is he real? Is he present in this room? He can’t be, of course. But what does it mean to be present? To be real? The music, the sound waves, are alive. Is his spirit encoded in these frequencies and amplitudes? Sakamoto once said he wanted to create music with “less notes and more spaces”. He insisted that this did not mean silence, but spaces between sounds that themselves could ring out, grow, and resonate. Resonance? Is that what this performance is about?

Questions bounce around my head as I listen to the opening of Kagami (Mirror). This mixed-reality concert was conceived of and produced by Sakamoto in collaboration with the Pittsburgh-based Tin Drum Studio. It premiered at New York’s The Shed in June of 2023, three months after his death from cancer at the age of 71.

Celebrated as one of Japan’s most charismatic composers, Sakamoto gained global recognition with a career that crossed cultural barriers and spanned multiple genres—from classical and electronic, through jazz and rock, to pop and folk. He left 21 solo albums, scored films (winning an Academy Award for The Last Emperor), dabbled as an actor, created music for commercials and soundscapes for multimedia artists. He also contributed music to the opening ceremony of the 1992 Barcelona Olympics and composed an opera exploring “the flux of matter and symbiosis of life.”

Youthful experiments with sequencers, samplers, synthesizers, and programable drum machines led to Sakamoto being recognized as the “godfather of electronic music.” He was credited with having opened a doorway to the coming digital age, but he would also engage in thoughtful explorations of subtle, organic sounds—raindrops filling an empty bucket, forest leaves underfoot, snow melting in the Arctic (“the purest sound I have ever heard”).

Underlying all his projects and endeavors was an insatiable creative appetite, an openness, and a willingness to experiment, cross boundaries, and forge connections. “Ryuichi was a

celebration of endless curiosity mixed with an astonishing lack of cynicism,” says Todd Eckert, Sakamoto’s friend and Tin Drum founder, who directed and produced Kagami. “This is why he was always creating new projects that worked. That spark of invention was always revealing itself to him.”

There are 80 people in the audience, sitting on chairs that form a circle. We had entered the dark room to find scenography consisting of only a few rectangles painted in the middle, suggesting an empty stage. This is where Sakamoto and his grand piano will appear. Before

that happens, we must mount transparent virtual-reality headsets, aptly named Magic Leap. Ten minutes or so into the concert experience, as Sakamoto begins playing ‘Energy Flow’, I decide to take a leap myself and walk towards the “stage.” (We are allowed to wander around the room during the performance). Getting closer, I toy with the idea of touching Sakamoto’s hair. Would I disrupt the flow? Would he be distracted? Raise his eyebrow? I know of course thatvirtual beings cannot be taken by surprise, but I do not want to “expose” him. I decide not to check. Instead, I walk to the other side of the piano, careful to avoid fellow concertgoers who are certainly real and possible to bump into! I remain still for a few moments, watching over Sakamoto’s shoulder, but I find myself unable to focus on the music. I can’t help examining his hands (the skin seems too smooth) and scrutinizing his movements (they are not fluid enough). Are his fingers actually touching the keys? It does not seem so.

The performance is one example of many recent artistic experiments with augmented and virtual reality. Described as a “multi-sensory experience,” Kagami fuses a three-dimensional, moving image of Sakamoto, with the here and now of the physical theater. Along with the musical performance, there are several digital projections—a tree that sprouts from the piano, light particles that resemble snow. There is also a unique scent in the room: a blend of lily, ginger, juniper, and lemon grass, created by Sakamoto and produced for the occasion by a Japanese artisan.

According to the production credits, scores of people, including lighting designers, UX design experts, “3D artists,” “server developers,” and even a “mesh surgeon,” were involved in the endeavor. The results are impressive but leave at least some viewers with a feeling of dissonance. “It feels like a wake in a laser tag arena,” wrote a New York Times critic. Others pointed to the high price of the headsets ($3,499 USD each) and compared the performance to a video game in which the main character has “unlocked the piano spirit level.” Todd Eckert of Tin Drum insists that it was never the intention to show off or engage in technological wizardry for its own sake. Nor was Kagami envisioned as a tribute to the late composer. “Memorial is always about a loss,” he said, adding that both he and Sakamoto were hoping Kagami would allow him to connect with audiences that he would otherwise not be able to reach.

“I wanted to create a relationship of energy and excitement for the audience—something present forever.” The plan for Kagami began to take shape in January of 2020, shortly before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Visiting Eckert’s Brooklyn apartment, Sakamoto shared an idea which had occupied him for some time: he wanted to create music that would have permanence, sounds that would not dissipate over time. Perhaps this was the result of reckoning with his own mortality. In 2014, Sakamoto had been diagnosed with laryngeal cancer. After months of treatment it went into remission, but the idea remained.

“I am fascinated with the notion of perpetual sound,” Sakamoto told Stephen Nomura Schilble, director and producer of the 2018 documentary Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda. “I suppose in literary terms it would be like a metaphor of eternity… Essentially the opposite of a piano because the notes never fade.” Paradoxically, the piano—his favorite Yamaha—would end up being the only instrument featured in Kagami. Sakamoto felt the piano was the instrument he had been closest to, almost an extension of his body. “It’s probably the easiest way to express my musicality, because I started playing the piano when I was three or four,” he told an interviewer. “When I imagine some music in my mind, almost automatically I imagine the piano keys.”

What Sakamoto probably did not imagine at this early stage was how many technical issues the production of Kagami would entail. “I honestly don’t think Ryuichi thought through [the technology] beyond what the process allowed,” Eckert says. As with his past projects, Sakamoto was keen on forging a new kind of connection with an audience. As their work on Kagami progressed, this need became even more urgent. Tin Drum producers had to address myriad technological and logistical challenges. For one thing, a grand piano, which Sakamoto wanted to use, would be difficult to handle in the 4D studio—given its size and complexity, it would occlude many camera shots. They considered using a keyboard with weighted keys and did several trial runs, but in the end, realizing how important it was to Sakamoto, Eckert gave in. “Ryuichi had a singular relationship with the piano and I wanted to present it in all its complexity and beauty.”

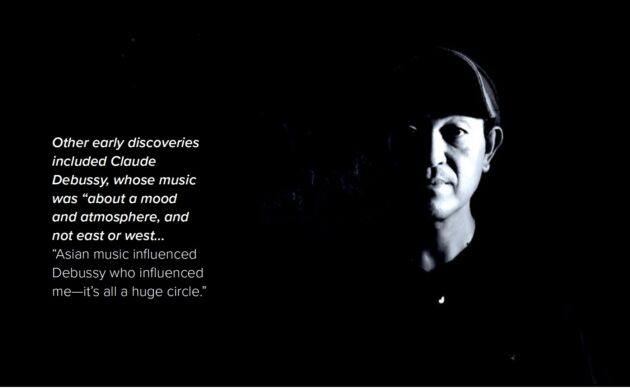

Born in Tokyo in 1952, Sakamoto did indeed begin playing and even composing for piano at an early age. Attending one of Japan’s most progressive kindergartens (which Yoko Ono had attended two decades earlier) he was also exposed to the arts. Sakamoto’s childhood was steeped in culture, his home often frequented by writers and artists. His father was an editor of renowned authors including Kenzaburo Oe and Yukio Mishima. His mother, a hat designer, took him to concerts of contemporary classical music while he was still a toddler. This is how he was introduced to the music of John Cage, whom he later credited as one of his most important influences. (Sakamoto liked to point out that he was born the same year that Cage’s ‘4′33’ was unveiled.) Other early discoveries included Claude Debussy, whose music was “about a mood and atmosphere, and not east or west,” as Sakamoto would explain decades later. “Asian music influenced Debussy who influenced me—it’s all a huge circle.”

The production of Kagami began in December of 2020. Despite Covid-19 restrictions, Sakamoto and Eckert flew from New York, where both were based, to Tokyo. Its Crescent Studio was just one of two places in the world with a volumetric motion capture, necessary for the project. The recording sessions lasted three days. As Sakamoto performed, the crew filmed him from multiple angles using 48 cameras. Additionally, tiny motion sensors were attached to his face and hands. To prevent his hair from falling and obscuring his face—as it often did in real life—they waxed it and put a net on top.

Unbeknown to Eckert, earlier that year Sakamoto had learned that his cancer had returned. Upon arriving in Tokyo, he went to see his oncologist and received more bad news: his tumor had metastasized. He did not share this with the production team, and Eckert only learned about it more than a year later. On that first morning in Crescent Studio, however, he did notice that Sakamoto was playing much more slowly, and his posture was hunched.

Once they finished recording and uploaded the data, it turned out that much of the time Sakamoto’s face had been blocked from the view of the camera. He had been leaning too low. As they would not be able to repeat the sessions, the only hope was to come up with some solution in postproduction. “It was an unprecedented process originated by Matt Hermans and Yoyo Munk that saved the project” says Eckert. The two—a 3D designer and a mesh surgeon respectively—were able to use the library of data that they had managed to gather during the recordings to recreate Sakamoto’s expression. “[Sakamoto’s] genuine spirit was the only reason for the project to happen in the first place,” says Eckert. “And even though the technology is in a nascent, imperfect state, his genuine humanity always comes through. If it didn’t, I wouldn’t have released it.”

After premiering in New York, Kagami traveled to the Manchester International Festival, and then to London. (It played at the Roundhouse from December 29, 2023 to January 21, 2024). Tin Drum is next planning to bring it to the Sydney Opera House and the Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, Tennessee. Eckert hopes Kagami will make it possible for the audiences to connect with Sakamoto’s music for many years to come. “This was my goal… To me, he played the way I wanted the world to sound, and I want to bring people closer to that forever.”

“Music, work, and life all have a beginning and an ending,” Sakamoto told an interviewer in early 2019. Hoping to transcend this cycle, he sought to create “music that could escape constraints of time.” One notable example involved playing a piano recovered from the 2011 Tōhoku tsunami. “I felt as if I was playing the corpse of a piano that had drowned,” he said after the concert for survivors in an abandoned school in Miyagi Prefecture. The waterlogged instrument had indeed been beyond repair, badly out of tune. Yet Sakamoto was able to find beauty in this distorted sound. “People say the sound of an untuned piano is ‘dissonant,’ but to me, the instrument has just gone back to its original state, to what it is supposed to be,” he told Asahi Shinbun, adding that he found the sound particularly comforting while he was fighting cancer. Both experiences—his terminal illness and the devastating natural disaster—helped him reckon with “the enormity of nature. We are only allowed to live on its palms. I never want to forget the lesson.”

As Kagami comes to an end, there are no encores. Sakamoto does not bow or leave the stage. He just fades away. We remove our headsets. As we leave the theater, I keep thinking about what the late musician said about the spaces between the notes. “Space is resonant, is still ringing. I want to enjoy that resonance, to hear it growing, then the next sound, and the next note or harmony can come.”

Thank you, Mr. Sakamoto.

There is, in reality, a virtual me.

This virtual me will not age and will continue to play the

piano for years, decades, centuries.

Will there be humans then?

Will the squids that will conquer the earth after humanity

listen to me?

What will pianos be to them?

What about music?

Will there be empathy there?

Empathy that spans hundreds of thousands of years.

Ah, but the batteries won’t last that long.

—Ryuichi Sakamoto, 2023

MAGDA RITTENHOUSE is a writer and photographer whose work focuses on nature and the built environment. The author of a best-selling book about New York, published by Czarne in her native Poland, she is currently working on a collection of essays and photographs on Japan. She has been a KJ contributor since 2018.

This article was published in KJ 106 (Cultural Fluidity) in February 2024.

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013