Murata Sayaka’s short novel, Convenience Store Woman, a thematically-propelled distillation of the author’s experience working in konbini, has achieved extraordinary success in English. In Translation speaks with the novel’s Ibaraki-based translator, Ginny Tapley Takemori.

GTT: I thought it would do well, but I’m blown away by how well. My translation of ‘A Clean Marriage’ had been published in Granta, and people were contacting me through Facebook saying, ‘I read this story and it’s amazing. Is there anything else by her coming out?’ I’ve never experienced that with anything I’ve translated. I knew that she was touching a chord with people. When Convenience Store Woman sold to foreign publishers, that shocked me as well, because it sold before the English translation came out, to something like fifteen publishers in fifteen languages. Normally publishers only become interested after a book has been published in English or French. It’s now sold to about 31 territories.

It’s an opportune moment for a book like this because there’s a lot of talk of women authors. Myself and Lucy North and Allison Markin Powell organized a symposium in Tokyo last November. That grew out of a worldwide—well, Western world-wide—awareness of the fact that not many women authors make it into English translation. Why not? Women authors in Japan are more or less par for winning the big prizes, and they’re publishing easily as much as men, but they’re not appearing in translation. There’s a movement to try and do something about it. In 2016 at the London Book Fair there was an impromptu meeting of about fifty translators from lots of different languages all brainstorming, ‘How can we get more women authors out there?’ One of the results was Women in Translation Month. Another was to have a series of articles on Lit Hub, 10 Women Authors We Want to See Published, from a given language.

Since all of this has been going on, I’ve had a lot of editors approach me, and a lot of agents, saying ‘We’re interested in women authors. Who should we be talking to?’ There is more interest, more awareness.

I did encounter Japanese literature through translations. It was very different from what I was used to. In some ways I found it a little unsatisfying, but on the other hand I found it intriguing. One of the things that I found intriguing was the fact that Japanese literary narratives don’t always have a beginning, middle and end. Coming from a Western background, this is challenging because you’re used to a satisfying ending, and in Japan it’s often left up in the air. I found that disconcerting, but fascinating. What was I supposed to think here?

The first Japanese author I read was Murakami, because a Japanese friend gave me some books. I was living in Barcelona at the time. I’d started collecting DragonBall manga series in Catalan, and watched anime on Catalan TV. I enjoyed it more than Disney and Western-style comics and animation, which tends to be all good and bad, black and white, and imposes a particular life view. I use that word—impose—because that’s how I see it now. It’s moralistic. I found the Japanese equivalent much more open-ended. It’s not so much black and white, good and evil. There’s a different purpose.

Absolutely. I find it much more open-ended, much less judgmental.

When I was working in a literary agency in Barcelona, we moved office and I came across this shelf of Japanese books translated into English, and I asked ‘What’s this all about?’ ‘Oh, we represent Japan Foreign Rights Centre, but it’s hard to sell these titles.’

I tried to sell them. I found that I could. A lot of effort was required, but I did sell some good titles. The Friends, for instance, by Yumoto Kazumi (translated by Cathy Hirano). There were quite a lot of books there and I was reading all of those. I found it overwhelming, this completely different vision of literature, and that’s what motivated me, ‘OK, I’ve got to study Japanese now.’

Some translators occasionally lament the predominance of Japan’s soft power exports, in the sense that it’s difficult to cultivate a literary audience among fans of manga and anime.

I don’t lament that at all. If they want to read my translations, I’m very happy. I’m not necessarily thinking of them when I’m translating. The work that I translate is literary. Not all manga fans will go on to read literature, but I think a lot of them do. They’re not just a bunch of shallow kids.

I don’t know what’s out there at the moment. My interest in manga is old now, but I do like it. I like the characters and the way they’re developed, the stories, the artwork. I like Miyazaki Hayao films. If I love all of that, there must be other literary-minded people who feel the same way. People have their own interests, and if they’re looking beyond their own culture, I think that’s already a good start.

In terms of expanding the canon of Japanese literature in English translation, I wonder if some of the books that really need translating are difficult to move across the language barrier. Karekinada, for instance, presents the problem of that alleyway dialect Nakagami dramatizes.

This is always a dilemma, but maybe you have to lose that element of it in English. But the contents of the speech itself could be very important, could be an interesting perspective. I’m of the opinion that capturing dialect and accents is kind of—

Just don’t do it?

You can capture a little flavor now and again. For the most part, don’t do it.

There might be ways. Works of theatre, for instance, might allow for translating dialect.

Louise Heal Kawai translated an excerpt of one of Kawakami Mieko’s books, Breasts and Eggs, into a Manchester accent. I thought what she did was really interesting.

I’m doing one at the moment. It’s a children’s book. You have two very different characters. One’s a sheep, which comes across as being female, and one’s a wolf, who is very ore—ore this, ore that, in a very masculine language. I’m having to work hard in English to bring out the two characters: the delicate little goat and the rough, uneducated wolf. It’s a challenge, but you can do it without using dialect, without having the specific words that Japanese has. English doesn’t have those differing word types, but there are other ways to access a rougher sort of language.

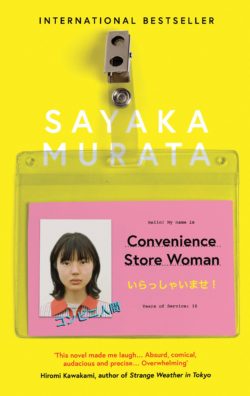

The convenience store itself is a fundamental part of the book, almost a character in its own right. For Japanese people, there’s one on every corner. It’s a familiar environment. For people abroad, they’re going to have no idea what this is—what a convenience store really is. I dedicated significant effort to reproducing this image in English, and to capturing the formulaic expressions the store workers use.

To give another example, Shiraha goes on and on about jomon jidai. I didn’t want to use ‘Jomon Period’ in English. People can look it up, but that distracts from the story. I used ‘Stone Age.’ The Jomon Period falls within the Stone Age, and I think it has a similar contextual image that English speakers will immediately latch onto.

It’s also an arubaito novel, in a sense, which is culturally specific. If everyone at the convenience store is a full-time employee with job security, the book changes.

The manager of the store is the one who buys the franchise. The head office controls how the manager runs his business, so it’s a really thankless job, actually. You have all these people coming from head office to regulate your work, to conduct inspections. Japanese people generally know this.

But that’s a career path Keiko can’t access, never mind a corporate career path. In the structure of the convenience store, all she can do is arubaito. I’ve had readers commenting, ‘When are they going to make her manager?’ In Japan that’s not possible.

Over the course of the novel, the language that Keiko uses to describe the store intensifies in some respects.

She starts describing the store as a living organism. The language she uses is striking in Japanese. It’s not a normal way of using language, necessarily. I didn’t want to smooth it over. It’s a fundamental part of the book. When she explains that the store rejects foreign objects if they don’t adapt to the organism, the language she uses is language of biology. It sounds weird in fiction, but it sounded weird in Japanese as well, so I wanted to preserve it. I think it’s important.

When she has Shiraha with her and she’s feeding him, she doesn’t cook, she ‘heat treats’ food. I had to try to keep the feel of that passage, where she’s keeping him like she’d keep a dog. She gives him food—esa in Japanese—as you would give it to animals, not humans. It took time to decide how to make it work in English. Keiko is so literal and so logical in the way she thinks. To us she sounds completely out there, but in her mind she’s completely logical.

The renowned editor John Freeman told me that Murata reminded him of the Argentine author Samanta Schweblin, and I think he’s right. It’s not so evident in Convenience Store Woman, but much of her work there is a similar undercurrent of horror. Keiko has it a bit. I loved that New York Times review where Dwight Garner said ‘You start going through your rolodex of loners. She’s less Ms. Havisham, less Babette, and more Norman Bates without the mommy issues.’ I thought, ‘OK, he really gets her.’

It’s almost like she’s saying that in order to be a woman and survive in this society, you have to get rid of your emotions. She’s not saying she’s against society. All her characters want to be part of it. It’s just that they can’t. They’re too far out there. In her latest novel, Chikyu seijin, she takes it one step further and describes society as a baby factory. You grow up and become part of this factory, fitting in. It’s a bit like being a cog in society in Convenience Store Woman. As a woman, your function is to be a baby machine. She’s not necessarily criticizing that. The protagonist, Natsuki, marries someone who is also alienated, but he is against society and rails against everybody for being brainwashed, while she’s sitting there thinking, ‘I wish I was brainwashed. It would be easier that way.’

I was interested how many readers and reviewers naturally assumed Keiko was on the autistic spectrum, which is not an issue for Japanese readers. And I’m not sure it’s true.

It’s an open question, isn’t it?

It’s an open question, but for Murata I think it’s kind of missing the point. Murata specifically doesn’t want Keiko to be seen as “ill” since she is simply going about her life not hurting anyone, yet other people find her disturbing because she is not living the life they think she should be.

Murata has created this character in order to shine a light on society. By being so different from everybody else, Keiko gives Murata—gives the reader—a perfect way to focus on the absurdities of what is considered normal. For me that’s more important, questioning what is considered normal.

I wonder if readers who tend to pathologize her behavior think she developed it in response to her occupation.

She was definitely like that before she went to the store. The store gave her an opportunity to be herself. It taught her to function as a member of society. That’s what she likes about the store. Otherwise, she has no idea. Throughout her life, everyone comes down on her like a ton of bricks when she exhibits behaviors which strike her as completely logical. She realizes that obviously it’s not right, because people are really angry with her about it. She has no idea why, but she has to try not to do that again. So she goes to the store and it’s this perfectly regular, regulated environment. Everything is done according to the manual, and you practice the manual. All the words you have to use, the things you say, what you wear, it’s regulated for you. She can feel safe there. She feels productive. Everybody’s happy with her because she can do it really well.

Murata actually wrote a story, which I translated, called ‘Love Letter to a Convenience Store.’* In the context of the book itself, if it’s from the point of view of making Keiko’s life worth living, I would say that the convenience store is her best environment. That’s where she can thrive. At times, it’s rendered in a kind of religious imagery. The convenience store is almost like a church.

*https://lithub.com/sayaka-muratas-love-letter-to-a-convenience-store/

My present self is formed almost completely of the people around me. I am currently made up of 30 percent Mrs. Izumi, 30 percent Sugawara, 20 percent the manager, and the rest absorbed from past colleagues such as Sasaki, who left six months ago, and Okasaki, who was our supervisor until a year ago.

My speech is especially inflected by everyone around me and is currently a mix of that of Mrs. Izumi and Sugawara. I think the same goes for most people. When some of Sugawara’s band members came into the store recently they all dressed and spoke just like her. After Mrs. Izumi came, Sasaki started sounding just like her when she said, “Good job, see you tomorrow!” Once a woman who had gotten on well with Mrs. Izumi at her previous store came to help out, and she dressed so much like Mrs. Izumi I almost mistook the two. And I probably infect others with the way I speak too. Infecting each other like this is how we maintain ourselves as human is what I think.

Outside work Mrs. Izumi is rather flashy, but she dresses the way normal women in their thirties do, so I take cues from the brand of shoes she wears and the label of the coats in her locker. Once she left her makeup bag lying around in the back room and I took a peek inside and made a note of the cosmetics she uses. People would notice if I copied her exactly, though, so what I do is read blogs by people who wear the same clothes she does and go for the other brands of clothes and kinds of shawls they talk about buying. Mrs. Izumi’s clothes, accessories, and hairstyles always strike me as the model of what a woman in her thirties should be wearing.

As we were chatting in the back room, her gaze suddenly fell on the ballet flats I was wearing. “Oh, those shoes are from that shop in Omotesando, aren’t they? I like that place too. I have some boots from there.” In the back room she speaks in a languid drawl, the end of her words slightly drawn out. I bought these flats after checking the brand name of the shoes she wears for work while she was in the toilet.

Dreux Richard is KJ’s In Translation Editor

Portraits of Ginny by Kit Nagamura www.kitnagamura.com